Purple Fox is an old threat that has been making waves since 2018. This most recent investigation covers Purple Fox’s new arrival vector and early access loaders. Users’ machines seem to be targeted with malicious payloads masquerading as legitimate application installers.

We have been continuously tracking the Purple Fox threat since it first made waves in 2018, when it reportedly infected over 30,000 users worldwide. In 2021 we covered how it downloaded and executed cryptocurrency miners, and how it continued to improve its infrastructure while also adding new backdoors.

This most recent investigation covers Purple Fox’s new arrival vector and the early access loaders we believe are associated with the intrusion set behind this botnet. Our data shows that users’ machines are targeted via trojanized software packages masquerading as legitimate application installers. The installers are actively distributed online to trick users and increase the overall botnet infrastructure. Other security companies have also reported on Purple Fox’s recent activities and their latest payloads.

The operators are updating their arsenal with new malware, including a variant of the remote access trojan FatalRAT that they seem to be continuously upgrading. They are also trying to improve their signed rootkit arsenal for antivirus (AV) evasion to be able to bypass security detection mechanisms. These notable changes are covered in the sections below and further explained in our technical brief.

Purple Fox infection chain and payload updates

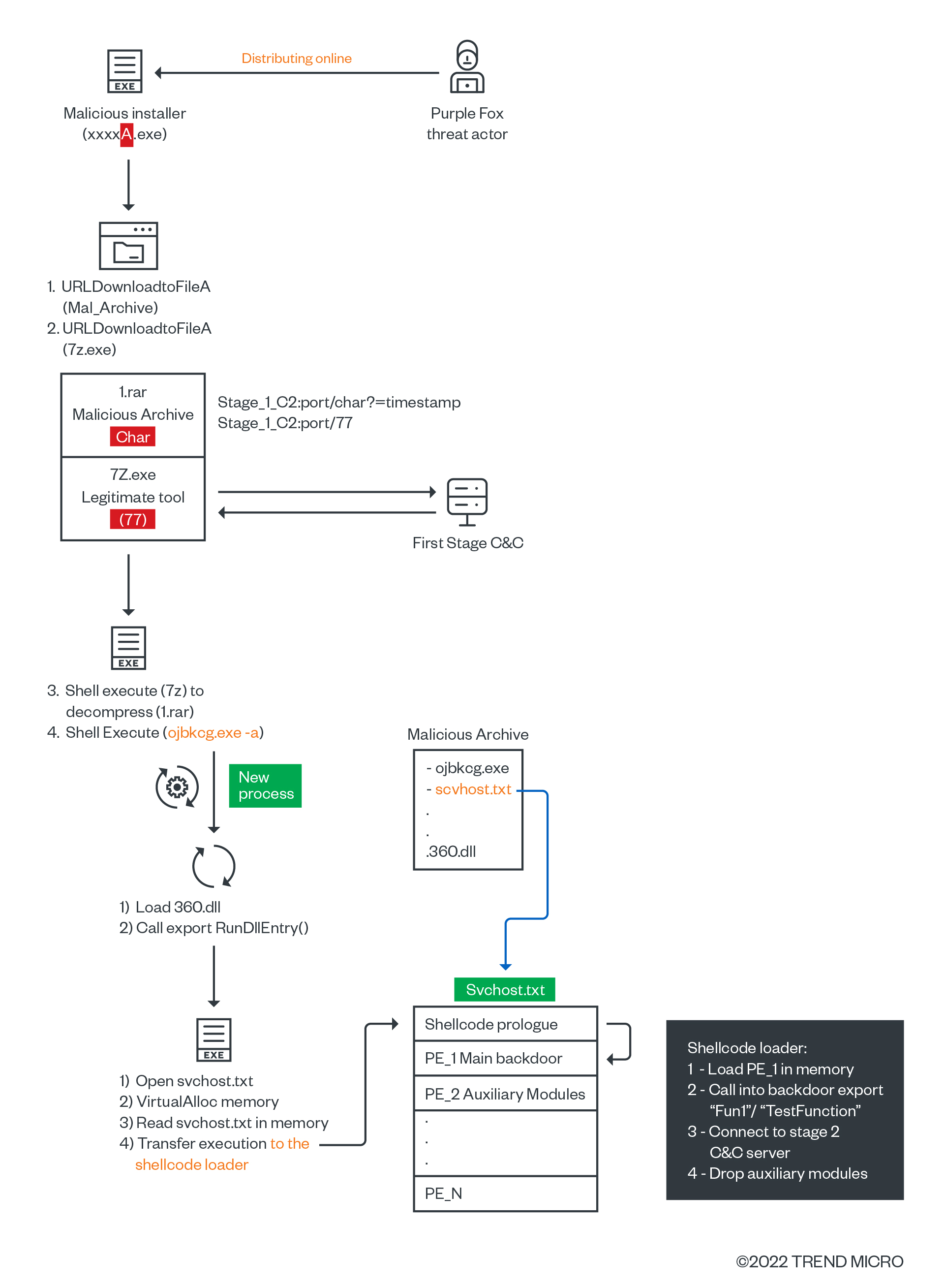

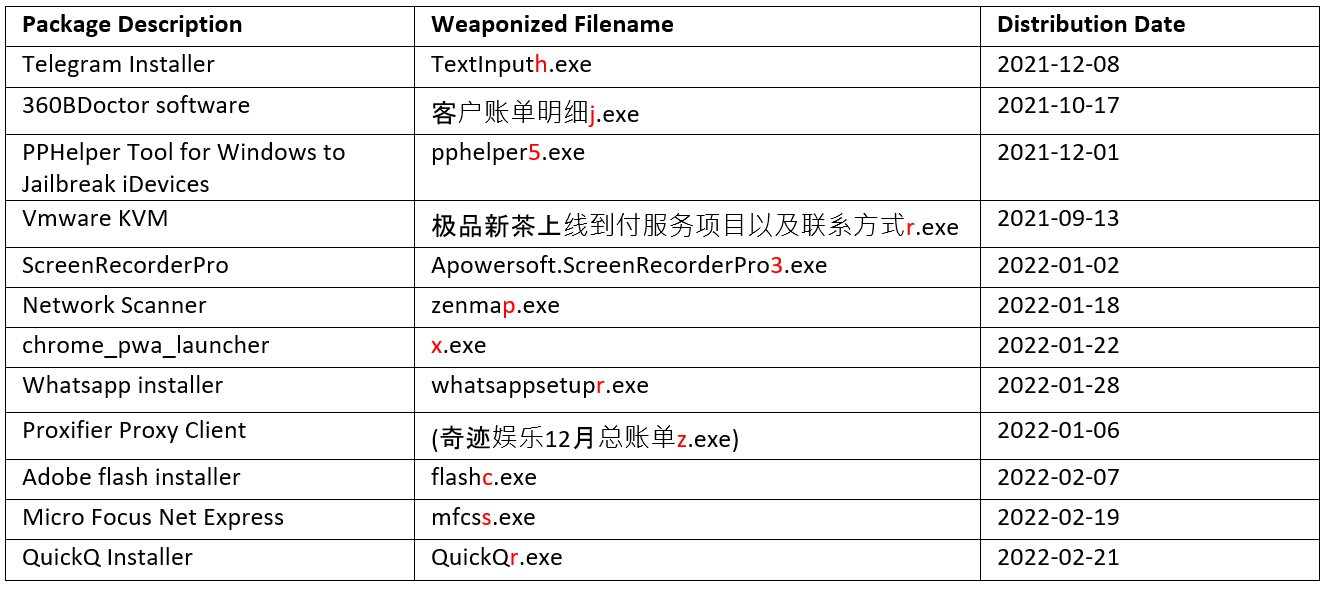

The attackers distribute their malware using disguised software packages that encapsulate the first stage loader. They use popular legitimate application names like Telegram, WhatsApp, Adobe, and Chrome to hide their malicious package installers.

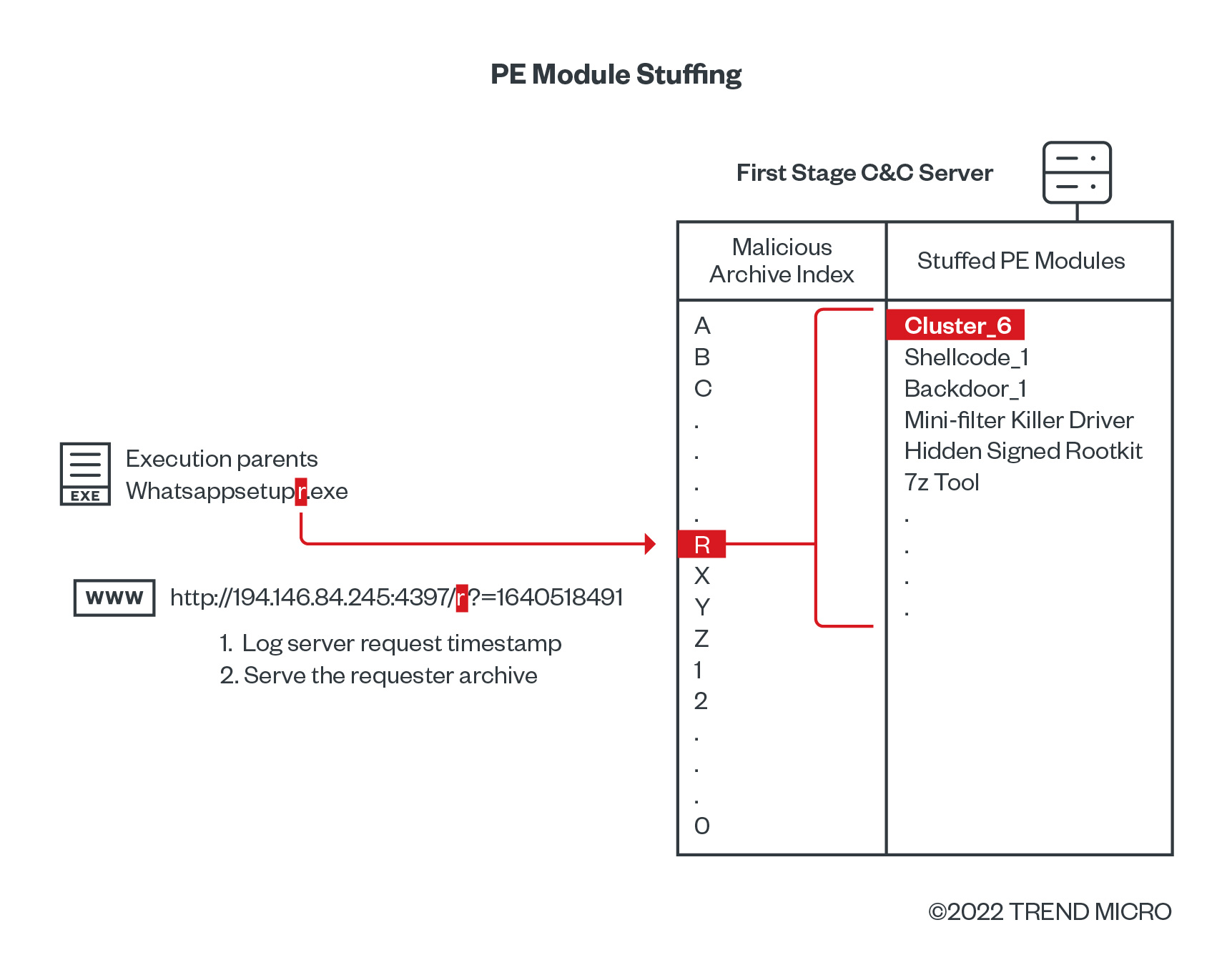

The installers include a specific single character (highlighted in Figure 1 as “A”) that corresponds to a specific payload. The second stage payload is added as the single character in the request sent by the execution parent to the first stage command and control (C&C) server (illustrated in detail in Figure 2 as “r”). It is retrieved through the module filename’s last character, then the first stage C&C server will log the execution timestamp sent in the request alongside the character. The single character will then determine what payloads will be sent back for the malicious installer to drop on the infected machine.

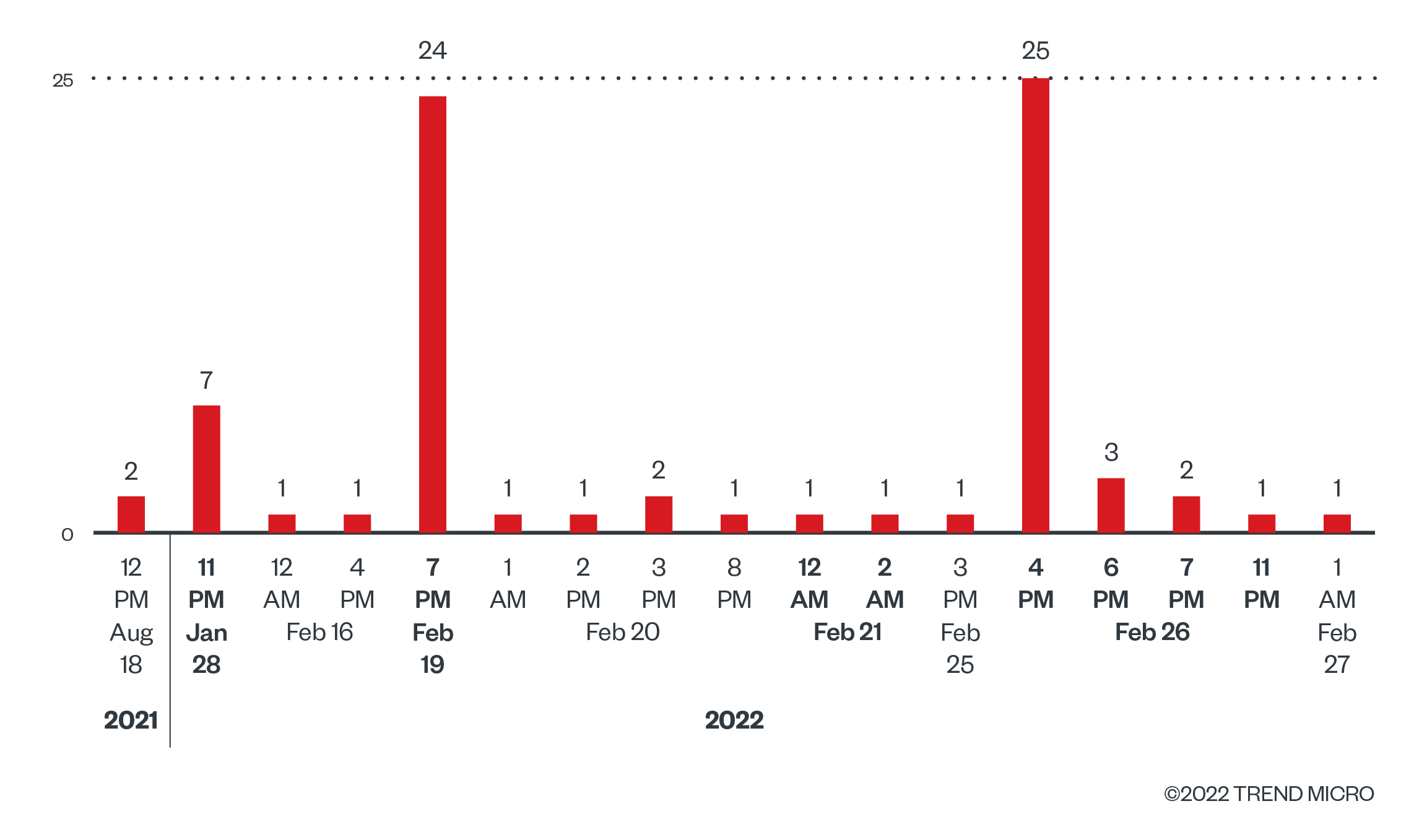

In previous campaigns in 2019, HTTP file servers (HFS) were used by Purple Fox to run the C&C servers that host files on the infected bots. In this most recent investigation, we found an exposed HFS that the Purple Fox group uses to host all the second stage samples with their update timestamps. We were able to track the frequency of the second stage updated packages pushed to this exposed server using the timestamp data. Figure 3 shows the number of different second stage malicious packages that received updates. They are still actively updating their components at the time of writing.

Notable Purple Fox tools and techniques

Disguised packages and malicious components in svchost.txt

We noted that some of the software they were impersonating were commonly used by Chinese users. The following list shows the recently used software and the corresponding malicious payload for the second stage of the infection. As mentioned above, the different payloads will be served by the C&C upon execution based on the last character in the module filename.

We tracked a server hosting the second stage payloads and saw a compressed RAR archive holding the second stage loaders along with the file svchost.txt, which contains all the malicious portable executable (PE) module components that will be dropped in the second stage.

The order of the PE modules inside svchost.txt is dependent on the package requested by the malicious installers. As previously mentioned, the last character in the installer filename will determine the final set of the auxiliary modules that will be stuffed inside svchost.txt.

Shellcode user-mode loader and anti-forensics methods

A specific set of portable executable (PE) modules found in one of the most distributed clusters from the malware had a wide range of capabilities in terms of AV evasion. This cluster is noteworthy for various reasons as well — it has links to older families, it loaded a previously documented Purple Fox MSI installer, and it had different rootkit capabilities in the auxiliary PE modules. More details about this cluster can be found in our technical brief.

After analyzing all the observed malicious execution parents delivering different clusters, we found that the shellcode component at the prologue of the dropped svchost.txt was similar across all the different variants, regardless of the actual payloads embedded after the shellcode. It has two different implementations across all the clusters.

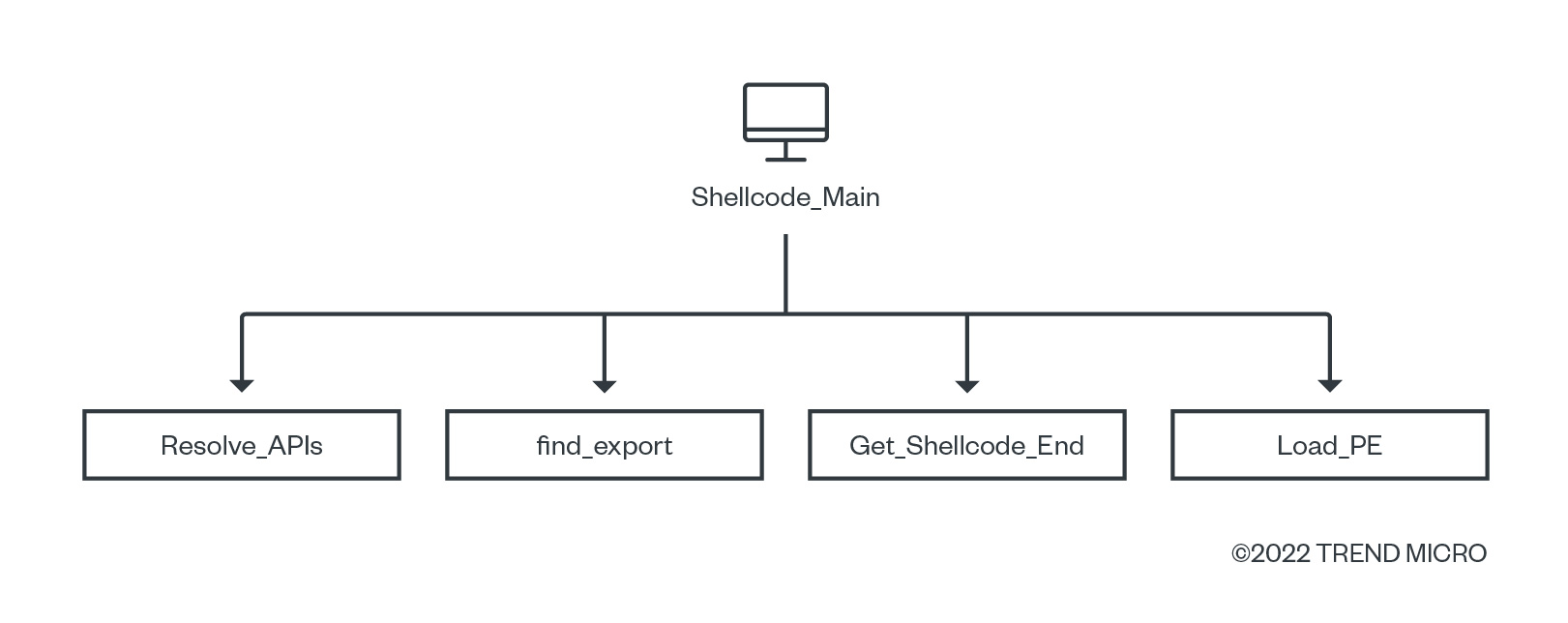

The first shellcode implements four main functions for the intended functionality, as shown in Figure 4.

Meanwhile, the new shellcode is more minimalistic because it implements only important functionalities to load a PE in memory and parse several system APIs addresses. It resolves different system APIs from the first one we mentioned.

One more thing to note: the Purple Fox group implements a customized user-mode shellcode loader that leaves little traces for cybersecurity forensics. It minimizes both the quantity and quality of the forensic evidence as the execution doesn’t rely on the native loader and doesn’t respect the PE format for a successful execution.

The use of FatalRAT and incremental updates

After the shellcode loads and allocates memory for the PE modules inside svchost.txt, the execution flow will call into the first PE module found after the shellcode. This is a remote access trojan (RAT) that inherits its functionality from a malware known as FatalRAT, a sophisticated C++ RAT that implements a wide set of remote capabilities for the attackers.

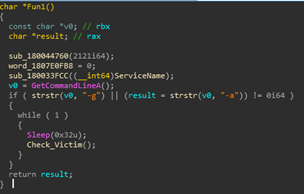

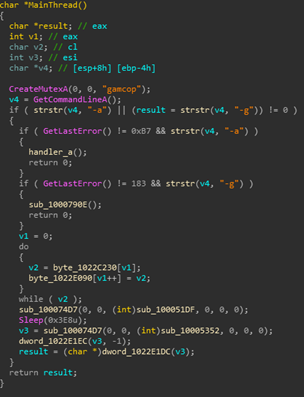

The executed FatalRAT variants shown in Figures 5 and 6 differ across each cluster, illustrating that the attackers are incrementally updating it.

The RAT is responsible for loading and executing the auxiliary modules based on checks performed on the victim systems. Changes can happen if specific AV agents are running or if registry keys are found. The auxiliary modules are intended as support for the group’s specific objectives.

New capabilities to evade cybersecurity mechanisms

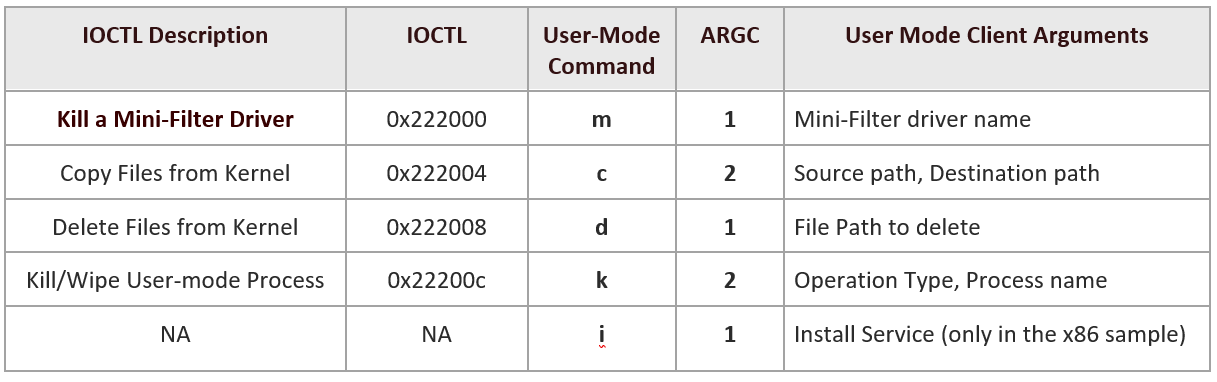

One of the analyzed executables embedded in svchost.txt is a user-mode client used to interface with the accompanying rootkit module. This client supports five different commands, each command implements a specific functionality to be executed from the kernel driver with the appropriate input/output control (IOCTL) interface exposed. Table 2 shows the details of each command:

The functionality to “kill a mini-filter” is notable in terms of AV evasion. File systems are targets for input-output (I/O) operations to access files, and file system filtering is the mechanism by which the drivers can intercept calls sent to the file system — this specifically is useful for AV agents. The model called ‘file system mini-filters’ was developed to replace the legacy filter mechanism. Mini-filters are easier to write and are the preferred way to develop file system filtering drivers in almost all AV engines.

We looked deeper into the mini-filter driver killer and how the attackers implemented this functionality. The driver first enumerates all the registered mini filter drivers on the system using the system API FltEnumerateFilters, then it gets the targeted mini-filter object information it is searching for by calling FltGetFilterInformation. Lastly, it creates a new system thread to unregister the mini-filter driver and terminate the created system thread (PsCreateSystemThread, FltUnregisterFilter).

Figure 7 shows the specific call graph for the system APIs used for this functionality.

The uses of revoked code signing certificates

To control the quality of the code that runs in the address space of the kernel-land, Microsoft only allows signed drivers to run in kernel mode. They do this by enforcing kernel-mode code signing (KMCS) mechanisms.

Due to performance issues and backward compatibility, Windows actually allows the loading of a kernel driver signed by a revoked code signing certificate. So, by testing a previous kernel driver and allowing it to be revoked, it can be loaded successfully. This design choice allows mature threat actors to chase and pursue any stolen code signing certificate and add it to their malware arsenal. If the malware authors acquire any certificate that has been verified by a trusted certificate authority and by Microsoft, even if it was revoked, attackers can use it for malicious purposes.

Links to previous Purple Fox activities and artifacts

Analyzing the artifacts dropped by this new infection chain, we first looked at the stolen code signing certificates used to sign the kernel drivers’ modules. This led us to analyze other signed malicious samples in our malware repository, which revealed links to previously known intrusion sets.

There were three different stolen code signing certificates confirmed to be related to this campaign with links to Purple Fox:

- Hangzhou Hootian Network Technology Co., Ltd. – We found a strong connection to early activity of the Purple Fox botnet that started in 2019.

- Shanghai Oceanlink Software Technology Co. Ltd. – Analysis revealed several clusters of malicious kernel modules previously used in Purple Fox activities.

- Shanghai easy kradar Information Consulting Co. Ltd. – This certificate overlaps with “Hangzhou Hootian Network” in signing a common cluster of kernel drivers that was also previously seen in Purple Fox activities.

This campaign is similar with earlier Purple Fox activities in other ways as well, namely, how the attack infrastructure is run and the malware hosted on their servers:

- The first stage C&C server 202[.]8.123[.]98 links FatalRAT operators with the Purple Fox. The server was hosting the malicious compressed archives in this campaign and was used before by FatalRAT as their main C&C server.

- One of the first stage servers (194.146.84.245) hosted an old module for the MSI installer for Purple Fox (e1f3ac7f.moe) that will eventually load the crypto miner discussed in the previous blogs.

- The dropped FatalRAT from the malicious archive found on the first stage C&C server revealed many code similarities with a previously documented info stealer known as Zegost. We go into commonalities found between these Purple Fox campaign modules and the old Zegost samples in our technical brief.

Conclusion

Operators of the Purple Fox botnet are still active and consistently updating their arsenal with new malware, while also upgrading the malware variants they have. They are also trying to improve their signed rootkit arsenal for AV evasion and trying to bypass detection mechanisms by targeting them with customized signed kernel drivers.

Abusing stolen code signing certificates and unprotected drivers are becoming more common with malicious actors. Software driver vendors should secure their code signing certificates and follow secure practices in the Windows kernel driver development process.

For more details on this topic download our technical brief and for the full list of the Indicators of Compromise download this document.