We discovered a new malware, which we named “OpcJacker” (due to its opcode configuration design and its cryptocurrency hijacking ability), that has been distributed in the wild since the second half of 2022.

We discovered a new malware, which we named “OpcJacker” (due to its opcode configuration design and its cryptocurrency hijacking ability), that has been distributed in the wild since the second half of 2022. OpcJacker is an interesting piece of malware, since its configuration file uses a custom file format to define the stealer’s behavior. Specifically, the format resembles custom virtual machine code, where numeric hexadecimal identifiers present in the configuration file make the stealer run desired functions. The purpose of using such a design is likely to make understanding and analyzing the malware’s code flow more difficult for researchers.

OpcJacker’s main functions include keylogging, taking screenshots, stealing sensitive data from browsers, loading additional modules, and replacing cryptocurrency addresses in the clipboard for hijacking purposes.

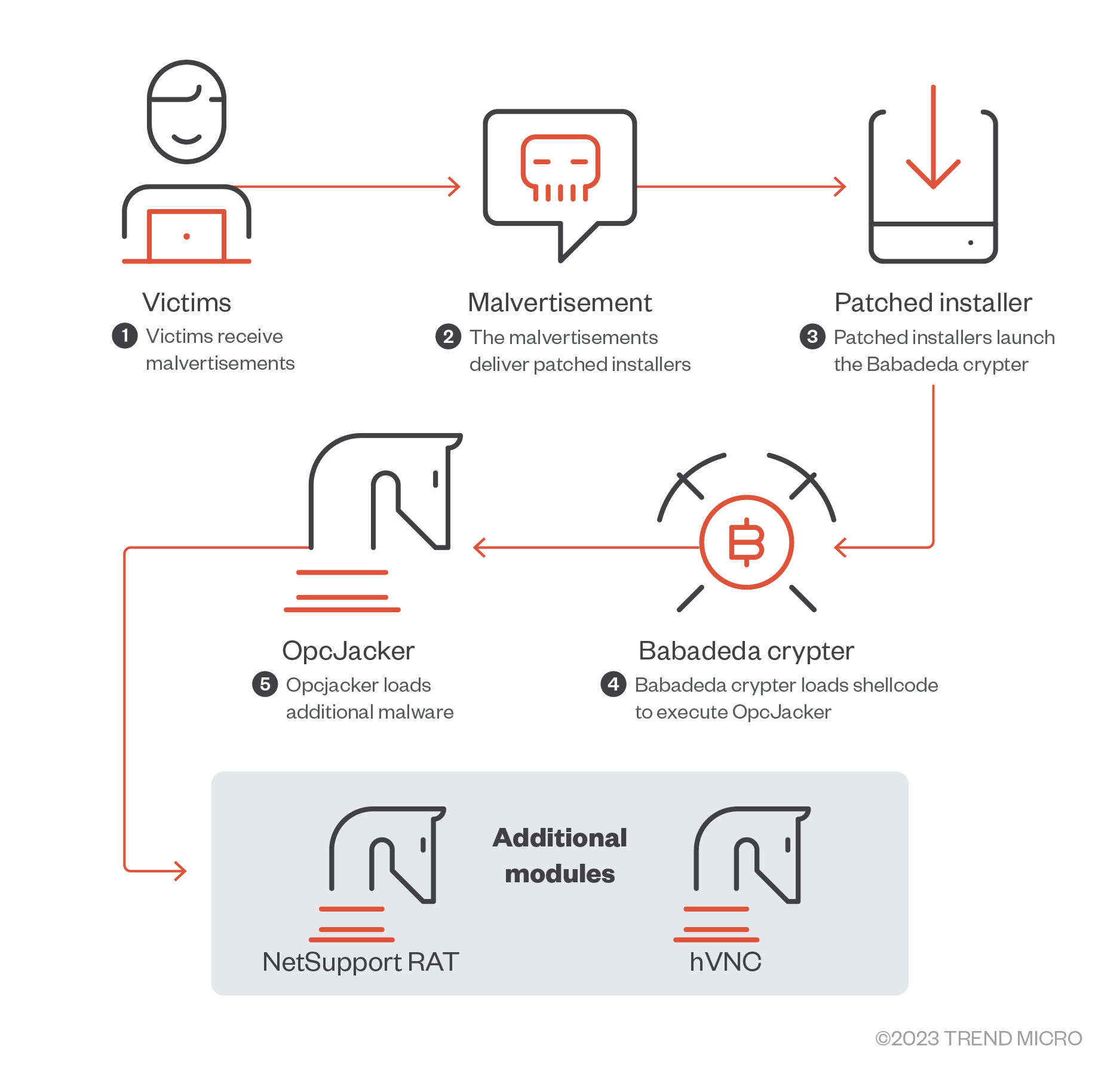

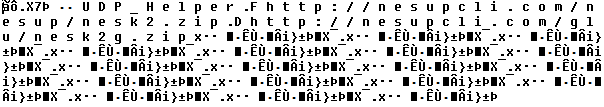

We’ve observed OpcJacker being distributed via different campaigns that involve the malware being disguised as cryptocurrency-related applications and other legitimate software, which the threat actors distribute through fake websites. In the latest (February 2023) campaign involving OpcJacker, the infection chain began with malvertisements that were geofenced to users in Iran. The malvertisements were disguised as a legitimate VPN service that tricked its victims into downloading an archive file containing OpcJacker.

The malware is loaded by patching a legitimate DLL library within an installed application, which loads another malicious DLL library. This DLL library then assembles and runs shellcode — the loader and runner of another malicious executable — and OpcJacker from chunks of data stored in data files of various formats, such as Waveform Audio File Format (WAV) and Microsoft Compiled HTML Help (CHM). This loader has been in use for over a year since it was previously described and named as the Babadeda crypter. The threat actor behind the campaign implemented a few changes in the cryptor itself, then added a completely new payload (a stealer/clipper/keylogger).

We noticed that OpcJacker mostly drops (or downloads) and runs additional modules, which are remote access tools — either the NetSupport RAT or a hidden virtual network computing (hVNC) variant. We also found a report sharing information on a loader called “Phobos Crypter” (which is actually the same malware as OpcJacker) being used to load the Phobos ransomware.

Delivery

As mentioned in the introduction, we observed OpcJacker being distributed through several different campaigns that usually involve fake websites advertising seemingly legitimate software and cryptocurrency-related applications, but are actually hosting malware. As these campaigns deliver a few other different malware in addition to OpcJacker, we believe that they are most likely to be different pay-per-install services leveraged by OpcJacker’s operators.

In the latest campaign from February 2023, we noticed OpcJacker being distributed via malvertisements geotargeting Iran. These malvertisements were linked to a malicious website disguised as a website for a legitimate VPN software. The site’s content was copied from the website of a legitimate commercial VPN service — however, the links were modified to link to a compromised website hosting malicious content.

The malicious website checks the client’s IP address to determine whether the victim uses a VPN service. If the IP address is not from a VPN service, it then redirects the victim to the second compromised website to lure them into downloading an archive file containing OpcJacker. Note that the attack will not proceed if the intended victim is using a VPN service.

Furthermore, we also found a bunch of ISO images and RAR/ZIP archives containing modified installers of various pieces of software that all lead to the loading of OpcJacker. These installers, which were previously used by other campaigns, were hosted on various hacked WordPress-powered websites or software development platforms like GitHub. A possible reason why threat actors favor the use of ISO files is to bypass Mark-of-the-Web warnings.

The following are some file name examples we found:

- CLF_security.iso

- Cloudflare_security_setup.iso

- GoldenDict-1.5.0-RC2-372-gc3ff15f-Install.zip

- MSI_Afterburner.iso

- tigervnc64-winvnc-1.12.0.rar

- TradingViewDesktop.zip

- XDag.x64.rar

Babadeda crypter

Note that the file names mentioned in this section often change between different installers. However, their overall functions remain the same.

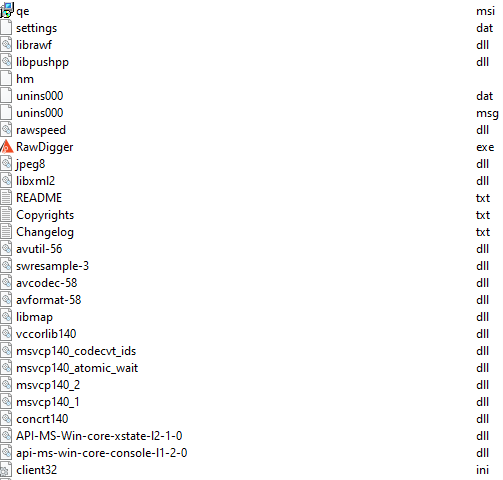

After the installer drops all the necessary files, it then loads the main executable file (RawDigger.exe), which is a clean legitimate file.

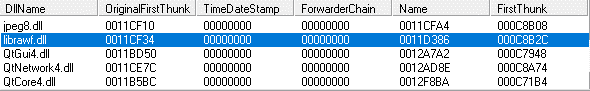

The executable file loads a DLL library that includes patched imports (librawf.dll).

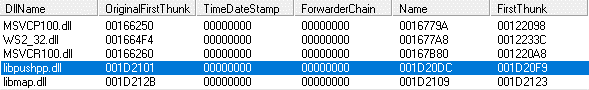

The patched DLL’s (librawf.dll, which is connected to the legitimate app RawDigger, a raw image analyzer) import address table was further patched to include two additional DLL libraries. In the figure below, notice how the FirstThunk addresses (of the newly added libraries) start with 001Dxxxx instead of the 0012xxxx used in the FirstThunk addresses from the original libraries.

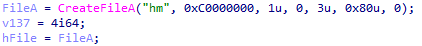

The highlighted library in Figure 5 (libpushpp.dll) is then loaded and executed. Its main task is to open one of the data files (hm) and load the first stage shellcode stored inside.

The offset and size of the first stage shellcode is hardcoded into the DLL library.

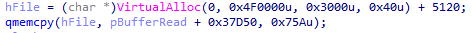

In newer versions of the Babadeda crypter, another DLL library (mdb.dll, from the fake VPN installer) is loaded into memory, after which a hardcoded, randomly selected block of memory is overwritten with the first stage shellcode. Note that this change is just a small detail and has no influence on the first stage shellcode’s overall function.

There is a configuration table containing offsets of encrypted chunks followed by their respective sizes at the end of the first stage shellcode. The first stage shellcode then decrypts and combines all chunks to form the second stage shellcode (a loader) and the main malware (OpcJacker with the ability to load additional malicious modules).

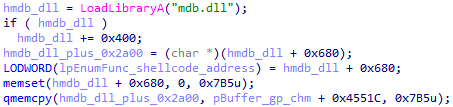

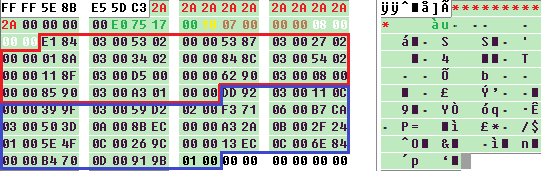

The configuration table starts with at least eight of the same characters (the red colored “*” in Figure 9, but different characters may be used in other samples), followed by the total length of the data file (green color; length of hm = 0x1775e0 = 1537504 bytes), the encryption key (yellow color; 0x18), the number of chunks in the second stage of the shellcode (brown color; 0x07), and finally, by the number of chunks in the main malware (white color; 0x08). The list of 0x07 (red bracket) and 0x08 (blue bracket) is equivalent to fifteen addresses and sizes of each chunk.

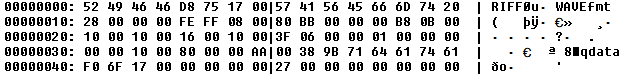

At the beginning of the data file (hm), we can see the (WAV) file header as it tries to mimic a WAVE file format. Note that the data file can be a different file format, since we also observed CHM being used.

Main stealer component (OpcJacker)

The main malware component (OpcJacker) is an interesting stealer that first decrypts and loads its configuration file. The configuration file format resembles a bytecode written in a custom machine language, where each instruction is parsed, individual opcodes are obtained, and then the specific handler is executed.

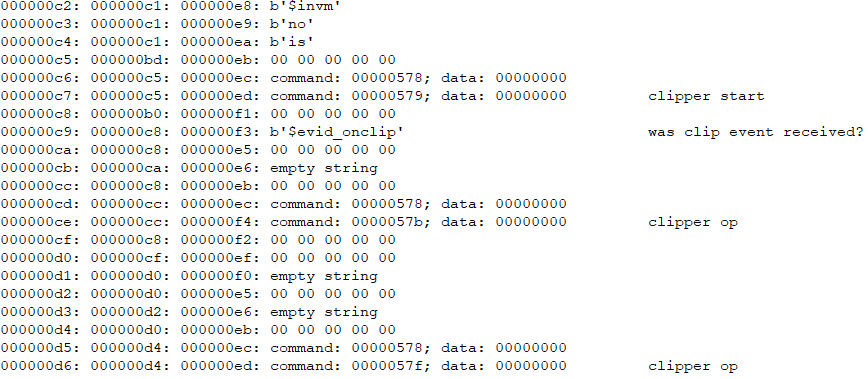

When analyzing the custom bytecode, we noticed the following patterns:

ASCII strings were encoded as 01 xx xx xx xx <string bytes>; where xx xx xx xx is the length of the string.

Similarly, wide character strings started with byte 02, while binary arrays started with byte 03.

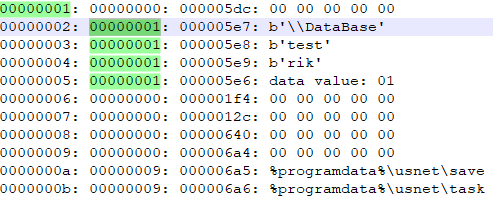

The configuration file format is a sequence of instructions where instruction starts with three 4-byte little-endian (DWORD) numbers. The first number is the virtual program counter, the second is likely the parent instruction’s virtual program counter, while the third is the handler ID (code to be executed in the virtual machine), followed by data bytes or additional handler IDs.

Based on these observations, we wrote an instruction parser, from which we were presented with the following output. Although our observations and understanding of the virtual machine’s internal implementation was incomplete, the parser gave us a good understanding of what behavior was defined in the configuration file.

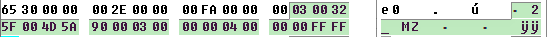

The decrypted and decoded configuration file starts with the initialization of certain system variables, with “test” and “rik” likely being campaign IDs. The configuration file dropped by SHA256 c5b499e886d8e86d0d85d0f73bc760516e7476442d3def2feeade417926f04a5 contains different keywords “test” and “ilk” as campaign IDs. Meanwhile, the configuration file dropped by the latest campaign from February 2023 (SHA256 565EA7469F9769DD05C925A3F3EF9A2F9756FF1F35FD154107786BFC63703B52) contains the keywords “test_installs” and “yorik.”

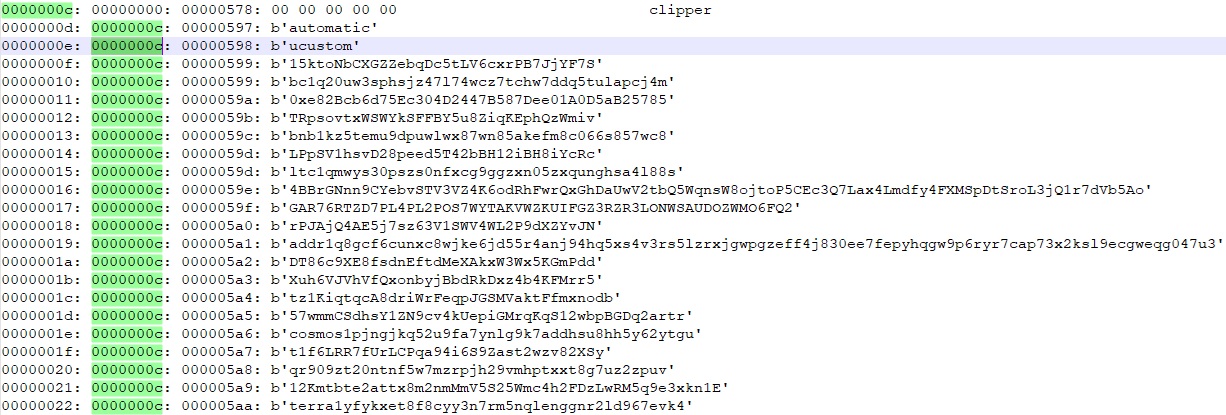

Then initialization of clipboard replacement functionality (clipping) follows.

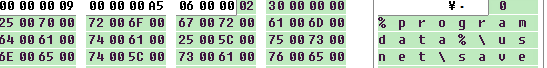

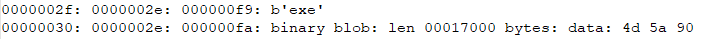

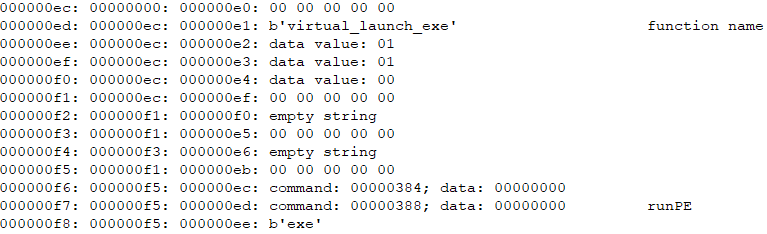

Later, the variable “exe” is initialized with executable file bytes (see the 4d 5a 90 = MZ marker). This executable is a remote access tool.

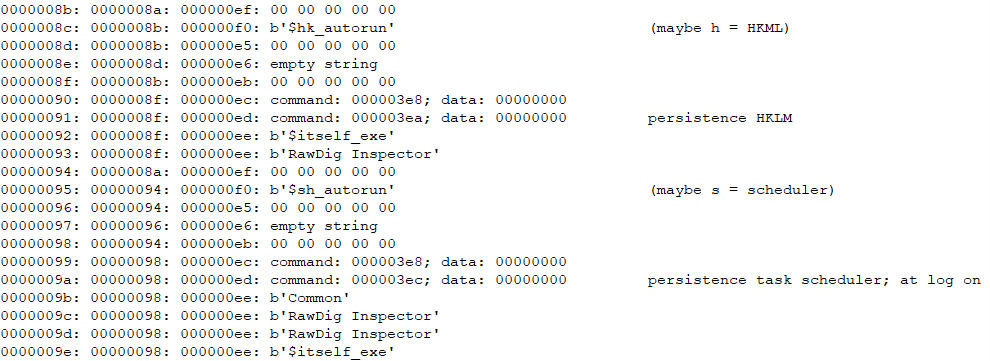

The malware sets up persistence via registry run and task scheduler methods. Note the $itself_exe variable used for holding the file name of the current process.

The malware then starts the clipper function, that is, it monitors the clipboard for cryptocurrency addresses and replaces them with its own cryptocurrency addresses controlled by the attackers.

Finally, the virtual_launch_exe function runs the previously embedded executable, which we observed to be RATs, either the NetSupport RAT, the NetSupport RAT downloader, or hVNC.

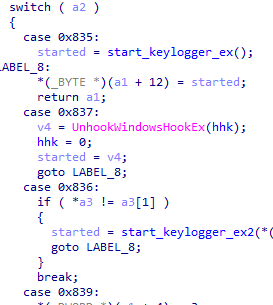

Handler IDs in custom virtual machines

As can be observed in the third column (or decoded “command” variable) in a few of the previous screenshots, the virtual machine implements numerous internal handlers. Most of these are related to various data manipulations. We list a few of the notable handlers that have specific high-level functionalities in Table 1. The functions the stealer implements include the following: clipping (clipboard content replacement), keylogging, file execution and listing, killing processes, stealing chromium credentials, detecting idleness, and detecting virtual machines. However, during our testing scenarios, we observed the stealer mostly just sets the persistence and delivers additional modules (remote access tools).

| Handler ID | Function |

|---|---|

| 0x3E9 | Used for persistence (registry; HKCU) |

| 0x3EA | Used for persistence (registry; HKLM) |

| 0x3EB | Used for persistence (startup folder) |

| 0x3EC;0x3ED | Used for persistence (task scheduler) |

| 0x7d1 | Lists files |

| 0x579 | Starts clipper |

| 0x57A | Stops clipper |

| 0x12d | Puts the machine into sleep mode |

| 0x385 | Terminates process |

| 0x387 | Exits process |

| 0x388; 0x38B | Runs PE executable |

| 0x389 | Runs shellcode |

| 0x38A | Runs PE executable export routine |

| 0x76D | Gets current committed memory limit (ullTotalPageFile) |

| 0x76E | Gets the amount of actual physical memory (ullTotalPhys) |

| 0x641 | Steals sensitive data from Chromium |

| 0x259 | Checks if the machine is idle and if the cursor is not moving |

| 0x25B | Checks if the machine is idle and if no new process is being created |

| 0x25D | Checks if the machine idle and if no new window is being created |

| 0x835 | Starts keylogger |

| 0x836 | Starts keylogger for a certain period |

| 0x837 | Stops keylogger |

| 0x839 | Copies data (likely logs) then return 0x83a (klogs) |

| 0x1F5 | Retrieves VMWare via CPUID |

| 0x1f7 | Searches for ‘virtual’ in SYSTEMControlSet001ServicesdiskEnum |

| 0x83A | Writes file(s) to klogs// |

| 0x89a | Writes file(s) to screenshots |

| 0x596 | Writes to clpclp_log.txt |

| 0xf6 | Writes file(s) to chromium_creds |

| 0xCE | Copies files to filesystem |

| 0x321 | Creates messagemonitor window, which needed for the clipper |

| 0x322 | Destroys messagemonitor window, which is needed for the clipper |

| 0x5DC | Gets environment ID |

| 0x5E0 | Runs GetModuleFileNameW, which is needed for resolving $itself_exe |

Table 1. Virtual machine command IDs

Embedded modules

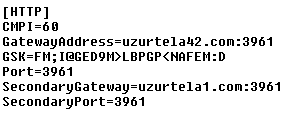

Some embedded modules contain the client32.exe (SHA256 18DF68D1581C11130C139FA52ABB74DFD098A9AF698A250645D6A4A65EFCBF2D or SHA256 49A568F8AC11173E3A0D76CFF6BC1D4B9BDF2C35C6D8570177422F142DCFDBE3) file from the NetSupport RAT. This single file is not enough, however, as the NetSupport tool needs additional DLL libraries and a configuration file. Note that these missing files have already been dropped by the modified installer into the installation directory.

For researchers, the most important file is called client32.ini, which contains important settings such as gateway addresses, gateway keys (GSK), and ports.

Some embedded modules contain the NetSupport RAT downloader (SHA256 C68096EB0A655924CA840EA1C71F9372AC055F299B52335AD10DDFA835F3633D). This downloader decrypts the URL payload, then downloads and executes it.

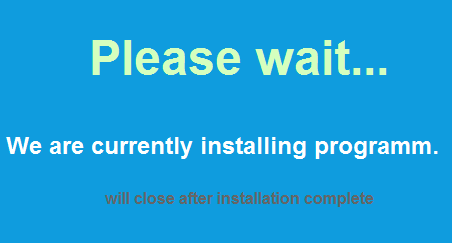

The decrypted configuration contains two URLs, one leading to an archive containing the NetSupport RAT, like the previous module, while the second contains a few batch scripts, which display messages such as the one seen in Figure 23. Later, one of these batch scripts downloads additional stealers.

Some embedded modules contain a modified hVNC module F772B652176A6E40012969E05D1C75E3C51A8DB4471245754975678F04DEDAAA. This module, in addition to standard remote desktop functionality, also contains routines to search for the existence of the following cryptocurrency related Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox extensions (wallets):

| Google Chrome extension ID | Extension name |

|---|---|

| ffnbelfdoeiohenkjibnmadjiehjhajb | Yoroi |

| ibnejdfjmmkpcnlpebklmnkoeoihofec | TronLink |

| jbdaocneiiinmjbjlgalhcelgbejmnid | Nifty Wallet |

| nkbihfbeogaeaoehlefnkodbefgpgknn | MetaMask |

| afbcbjpbpfadlkmhmclhkeeodmamcflc | Math Wallet |

| hnfanknocfeofbddgcijnmhnfnkdnaad | Coinbase Wallet |

| fhbohimaelbohpjbbldcngcnapndodjp | Binance Wallet |

| odbfpeeihdkbihmopkbjmoonfanlbfcl | Brave Wallet |

| hpglfhgfnhbgpjdenjgmdgoeiappafln | Guarda Wallet |

| blnieiiffboillknjnepogjhkgnoapac | Equall Wallet |

| cjelfplplebdjjenllpjcblmjkfcffne | Jaxx Liberty |

| fihkakfobkmkjojpchpfgcmhfjnmnfpi | BitApp Wallet |

| kncchdigobghenbbaddojjnnaogfppfj | iWallet |

| amkmjjmmflddogmhpjloimipbofnfjih | Wombat |

| fhilaheimglignddkjgofkcbgekhenbh | Oxygen |

| nlbmnnijcnlegkjjpcfjclmcfggfefdm | MyEtherWallet |

| nanjmdknhkinifnkgdcggcfnhdaammmj | GuildWallet |

| nkddgncdjgjfcddamfgcmfnlhccnimig | Saturn Wallet |

| fnjhmkhhmkbjkkabndcnnogagogbneec | Ronin Wallet |

| aiifbnbfobpmeekipheeijimdpnlpgpp | Station Wallet |

| fnnegphlobjdpkhecapkijjdkgcjhkib | Harmony |

| aeachknmefphepccionboohckonoeemg | Coin98 |

| cgeeodpfagjceefieflmdfphplkenlfk | EVER Wallet |

| pdadjkfkgcafgbceimcpbkalnfnepbnk | KardiaChain |

| bfnaelmomeimhlpmgjnjophhpkkoljpa | Phantom |

| fhilaheimglignddkjgofkcbgekhenbh | Oxygen |

| mgffkfbidihjpoaomajlbgchddlicgpn | Pali |

| aodkkagnadcbobfpggfnjeongemjbjca | BoltX |

| kpfopkelmapcoipemfendmdcghnegimn | Liquality |

| hmeobnfnfcmdkdcmlblgagmfpfboieaf | XDEFI |

| lpfcbjknijpeeillifnkikgncikgfhdo | Nami |

| dngmlblcodfobpdpecaadgfbcggfjfnm | MultiversX DeFi |

Table 2. Targeted Chrome extensions

| Microsoft Edge extension ID | Extension name |

|---|---|

| akoiaibnepcedcplijmiamnaigbepmcb | Yoroi |

| ejbalbakoplchlghecdalmeeeajnimhm | MetaMask |

| dfeccadlilpndjjohbjdblepmjeahlmm | Math Wallet |

| kjmoohlgokccodicjjfebfomlbljgfhk | Ronin Wallet |

| ajkhoeiiokighlmdnlakpjfoobnjinie | Terra Station |

| fplfipmamcjaknpgnipjeaeeidnjooao | BDLT wallet |

| niihfokdlimbddhfmngnplgfcgpmlido | Glow |

| obffkkagpmohennipjokmpllocnlndac | OneKey |

| kfocnlddfahihoalinnfbnfmopjokmhl | MetaWallet |

Table 3. Targeted Edge extensions

| Mozilla Firefox extension ID | Extension name |

|---|---|

| {530f7c6c-6077-4703-8f71-cb368c663e35}.xpi | Yoroi |

| ronin-wallet@axieinfinity.com.xpi | Ronin Wallet |

| webextension@metamask.io.xpi | MetaMask |

| {5799d9b6-8343-4c26-9ab6-5d2ad39884ce}.xpi | TronLink |

| {aa812bee-9e92-48ba-9570-5faf0cfe2578}.xpi | |

| {59ea5f29-6ea9-40b5-83cd-937249b001e1}.xpi | |

| {d8ddfc2a-97d9-4c60-8b53-5edd299b6674}.xpi | |

| {7c42eea1-b3e4-4be4-a56f-82a5852b12dc}.xpi | Phantom |

| {b3e96b5f-b5bf-8b48-846b-52f430365e80}.xpi | |

| {eb1fb57b-ca3d-4624-a841-728fdb28455f}.xpi | |

| {76596e30-ecdb-477a-91fd-c08f2018df1a}.xpi |

Table 4. Targeted Firefox extensions

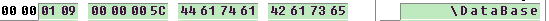

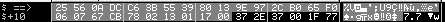

In our analyzed sample, command-and-control (C&C) communication starts with the following magic:

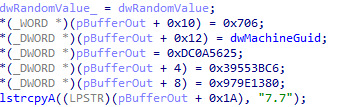

The snippet below shows that some values are hardcoded into the executable, others are generated from MachineGuid or randomly generated. Note the string “7.7” seen in Figure 25, which is likely the modified hVNC version.

Conclusion

It seems that OpcJacker’s operator is motivated by financial gain, since the malware’s primary purpose is stealing cryptocurrency funds from wallets. However, its versatile functions also allow OpcJacker to act as an information stealer or a malware loader, meaning it can be used beyond its initial intended use.

The campaign IDs we found in the samples, such as “test” and “test_installs”, indicate that OpcJacker could still be under development and testing stages. Given its unique design combined with a variety of VM-like functionalities, it’s possible that the malware could prove to be popular with threat actors, and therefore could see use in future threat campaigns.

Indicators of Compromise

The indicators for this blog entry can be found here.