Anyone who has had to deal with HTML emails on a technical level has probably reached the point where they wanted to quit their job or just set fire to all the mail clients due to their inconsistent implementations. But HTML emails are not just a source of frustration, they can also be a serious security risk.

Imagine you receive an email forwarded by your manager asking you to wire a large sum of money to a bank account. Of course, you have heard of CEO fraud, so you double-check that the email really comes from your manager. It does, and it may even be cryptographically signed – if you do that in your company. However, you are still not convinced, so you call your manager to ensure that the email is legit. He confirms, so you transfer the money.

Yet this would be the end of the article if this wasn’t a scam. So what went wrong?

Kobold letters

The email your manager received and forwarded to you was something completely innocent, such as a potential customer asking a few questions. All that email was supposed to achieve was being forwarded to you. However, the moment the email appeared in your inbox, it changed. The innocent pretext disappeared and the real phishing email became visible. A phishing email you had to trust because you knew the sender and they even confirmed that they had forwarded it to you.

This attack is possible because most email clients allow CSS to be used to style HTML emails. When an email is forwarded, the position of the original email in the DOM usually changes, allowing for CSS rules to be selectively applied only when an email has been forwarded.

An attacker can use this to include elements in the email that appear or disappear depending on the context in which the email is viewed. Because they are usually invisible, only appear in certain circumstances, and can be used for all sorts of mischief, I’ll refer to these elements as kobold letters, after the elusive sprites of mythology.

This affects all types of email clients and webmailers that support HTML email. So pretty much all of them. For the moment, however, I’ll focus on selected clients to demonstrate the problem, and leave it to others (or future me) to extend the principle to other clients.

Thunderbird

This issue was reported to Mozilla on 05.03.2024.

The planned release date and a draft of the following section were communicated to Mozilla on 20.03.2024.

Possible mitigations have been discussed but will not be implemented until a later date.

Exploiting this in Thunderbird is fairly straightforward. Thunderbird wraps emails in <div class="moz-text-html" lang="x-unicode"></div> and leaves them otherwise unchanged, making it a good example to demonstrate the principle. When forwarding an email, the quoted email will be enclosed in another <div></div>, moving it down one level in the DOM.

Taking this into account leads to the following proof of concept:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<style>

.kobold-letter {

display: none;

}

.moz-text-html>div>.kobold-letter {

display: block !important;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p>This text is always visible.</p>

<p class="kobold-letter">This text will only appear after forwarding.</p>

</body>

</html>

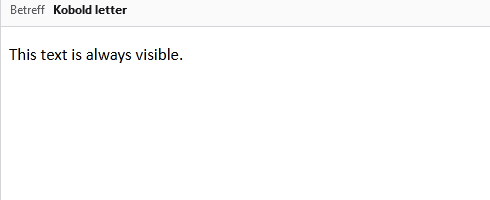

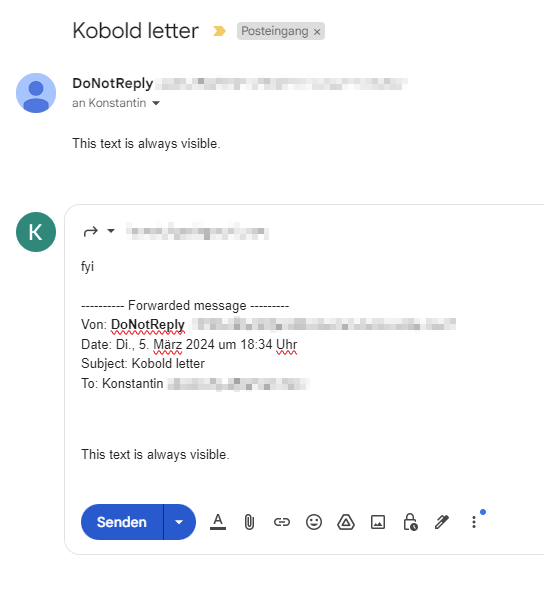

The email contains two paragraphs, one that has no styling and should always be visible, and one that is hidden with display: none;. This is how it looks when the email is displayed in Thunderbird:

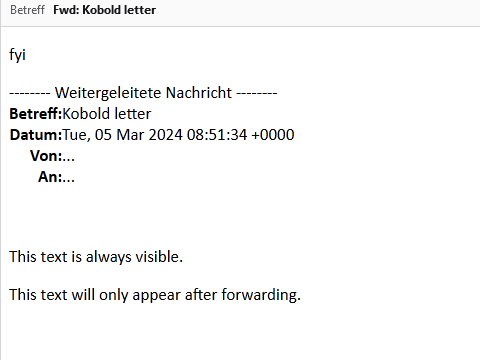

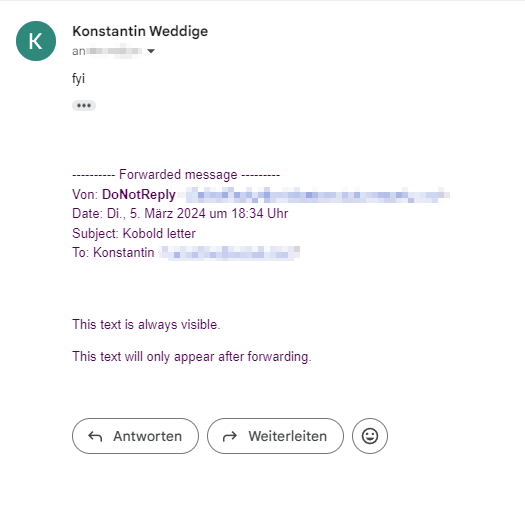

As expected, only the paragraph “This text is always visible.” is shown. However, when we forward the email, the second paragraph becomes suddenly visible. Albeit only to the new recipient – the original recipient who forwarded the email remains unaware.

Because we know exactly where each element will be in the DOM relative to .moz-text-html, and because we control the CSS, we can easily hide and show any part of the email, changing the content completely. If we style the kobold letter as an overlay, we can not only affect the forwarded email, but also (for example) replace any comments your manager might have had on the original mail, opening up even more opportunities for phishing.

Outlook on the web

This issue was reported to Microsoft on 05.03.2024.

The planned release date and a draft of the following section were communicated to Microsoft on 20.03.2024.

The report was marked as closed by Microsoft on 26.03.2024 after deciding not to take any immediate action.

In Outlook on the web (OWA) the situation is slightly more complicated, as it is a webmailer. Emails are contained in <div class="rps_78fa"></div>, but the exact class name will change. To prevent the CSS of emails to affect the style of the webmailer, Outlook modifies the email by prefixing all ids and classes with x_ and adjust the CSS accordingly.

Considering all this, we get the following proof of concept:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<style>

.kobold-letter {

display: none;

}

body>div>.kobold-letter {

display: block !important;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p>This text is always visible.</p>

<p class="kobold-letter">This text will only appear after forwarding.</p>

</body>

</html>

When the email is displayed by OWA, the CSS will look like this:

<style>

<!--

.rps_78fa .x_kobold-letter

{display:none}

.rps_78fa > div > div > .x_kobold-letter

{display:block!important}

-->

</style>

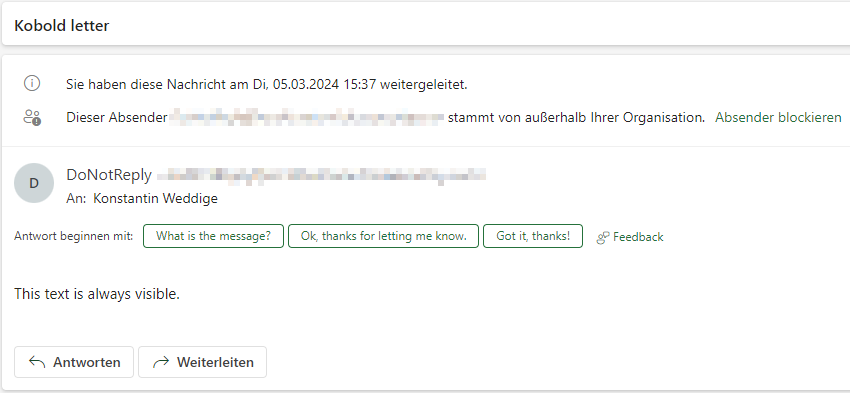

The email will be displayed as expected:

After forwarding, the kobold letter will be enclosed by another <div> and the CSS will be updated again:

<style>

<!--

.rps_78fa .x_x_kobold-letter

{display:none}

.rps_78fa div > div > .x_x_kobold-letter

{display:block!important}

-->

</style>

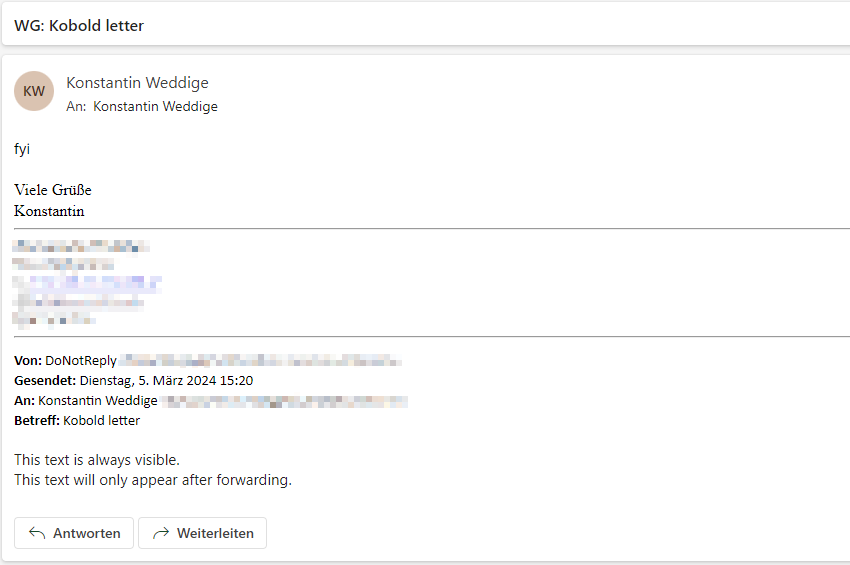

Note that in the second rule, the > between .rps_78fa and div has been dropped. This must be taken into account when creating more complicated selectors. Our proof of concept works as intended:

The adjustments that OWA applies to the email do not interfere with the attack, but need to be considered when crafting a kobold letter. As we don’t have an easily recognizable anchor point, this can become a nuisance when trying to create a kobold letter that works for multiple clients at the same time.

Gmail

This issue was reported to Google on 05.03.2024.

The planned release date and a draft of the following section were communicated to Google on 20.03.2024.

Google confirmed on 09.04.2024 that they are working on a fix.

So far, we could define kobold letters as elements that use CSS selectors to be shown or hidden depending on the context in which the email is displayed. By this definition, Gmail is technically not vulnerable to kobold letters because it strips all styling from the email when forwarding it.

This allows for an even simpler – albeit more limited – attack: It is now sufficient to hide the kobold letter with CSS, and it will automatically appear when forwarded. However, this does not allow the opposite behaviour, where the kobold letter is visible in the original email and invisible in the forwarded email.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<style>

.kobold-letter {

display: none;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p>This text is always visible.</p>

<p class="kobold-letter">This text will only appear after forwarding.</p>

</body>

</html>

This is aided by the fact that when the email is forwarded, the CSS is not removed until after it has been sent:

While the second paragraph was clearly not visible in the editor, it is in the resulting email:

While it is difficult to fix kobold letters in general without breaking too much, Google could mitigate the problem by removing the CSS already in the editor. This would at least allow the sender to detect the attack before forwarding the email.

Prior work

The fact that this is possible in one way or another is neither surprising nor new. Therefore similar issues have been reported in the past:

- Thunderbird – Modification of replied mail content without knowledge of replier of the mail using CSS

- Treat OpenPGP/SMIME email messages with certain CSS elements as unsigned

- Composition should use inline styling so that styles from quotes don’t leak into the message

The novelty of kobold letters lies in the focus on a specific attack scenario, while looking at multiple email clients. This hopefully will help raise awareness of the risks associated with HTML emails and contribute to the discussion of what trade-offs are acceptable to mitigate these risks.

Outlook (not the software)

Users can mitigate kobold letters by disabling HTML email altogether or viewing it in a restricted mode (e.g. “plain HTML” in Thunderbird). For email clients, it is more difficult to implement a mitigation, as preventing the use of <style>1 would fix this, but would also break a lot of existing solutions in the email ecosystem. An implementation like the one Google already uses for Gmail could be a compromise that allows for stylized corporate newsletters while limiting the risks of HTML email.

Unfortunately, for the foreseeable future, it is sadly not realistic to expect email clients to implement robust mitigation. This means that it is up to the users to be aware of the dangers of HTML emails and to take the necessary precautions.

https://lutrasecurity.com/en/articles/kobold-letters