Key Point :

——————————

– Operation Cronos disrupted LockBit’s operations, leading to outages on LockBit-affiliated platforms and a takeover of its leak site by the UK’s National Crime Agency.

– Authorities used the compromised leak site to distribute information about LockBit, highlighting the risks of paying ransoms and the impact on affected businesses.

– Trend Micro analyzed LockBit-NG-Dev, revealing a shift to .NET core and the need for new security detection techniques.

– The leak of LockBit’s back-end information exposed affiliate identities and victim data, potentially damaging trust within the cybercriminal network.

– The cybercrime community had mixed reactions to LockBit’s disruption, with speculation about the group’s future and impacts on the RaaS industry.

– Activities post-disruption indicated a significant impact on LockBit’s operations, contrary to the group’s claims.

Our new article provides key highlights and takeaways from Operation Cronos’ disruption of LockBit’s operations, as well as telemetry details on how LockBit actors operated post-disruption.

Summary:

- On Feb. 19, 2024, Operation Cronos, a targeted law enforcement action, caused outages on LockBit-affiliated platforms, significantly disrupting the notorious ransomware group’s operations.

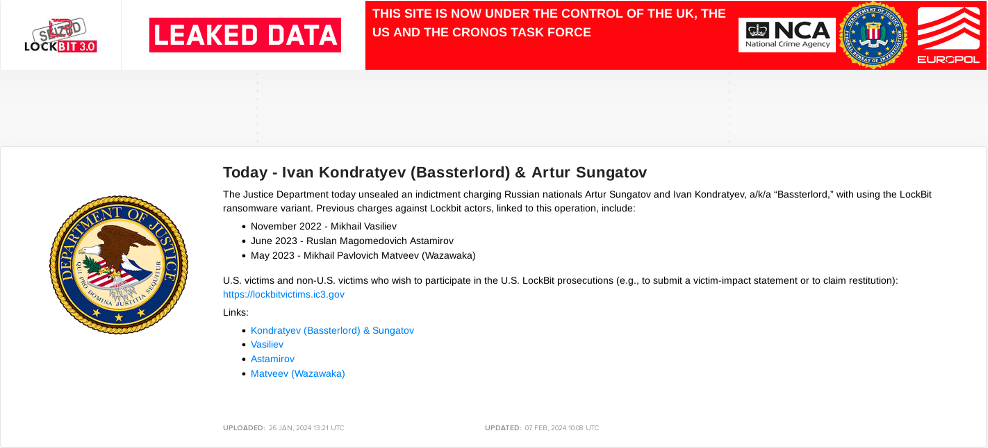

- LockBit’s downtime was quickly followed by a takeover of its leak site by the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA), spotlighting the concerted international effort against cybercrime.

- Authorities leveraged the compromised LockBit leak site to distribute information about the group and its operations, announce arrests, sanctions, cryptocurrency seizure, and more. This demonstrated support for affected businesses and cast doubt on LockBit’s promises regarding data deletion post-ransom payment — emphasizing that paying ransoms is not the best course of action.

- Trend Micro analyzed LockBit-NG-Dev, an in-development version of the ransomware. Key findings indicated a shift to a .NET core, which allows it to be more platform-agnostic and emphasizes the need for new security detection techniques.

- The leak of LockBit’s back-end information offered a glimpse into its internal workings and disclosed affiliate identities and victim data, potentially leading to a drop in trust and collaboration within the cybercriminal network.

- The sentiments of the cybercrime community to LockBit’s disruption ranged from satisfaction to speculation about the group’s future, hinting at the significant impact of the incident on the ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) industry. Businesses can expect shifts in RaaS tactics and should enhance preparedness against potential reformations of the disrupted group and its affiliates.

- Contrary to what the group themselves have stated, activities observed post-disruption would indicate that Operation Chronos has a significant impact on the group’s activities.

Overview of Operation Cronos

The RaaS group LockBit that has been in operation since early 2020, grew to become one of the largest RaaS groups in the ransomware ecosphere and was responsible for 25% to 33% of all ransomware attacks in 2023. The group has claimed thousands of victims and was, by far, the biggest financial threat actor group in 2023.

The LockBit group operated using an affiliate model, whereby the group claimed 20% of ransom payments with the remainder going to affiliates responsible for the ransomware attacks. This report outlines how LockBit operated, and most importantly, the subsequent activity we observed following the disruption of its operations.

On Feb. 19, 2024, at around 8 p.m. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), we observed that several of the Onion sites associated with the LockBit operation were showing a 404 error message.

After determining that the various Onion sites refused any connection, Operation Cronos was underway.

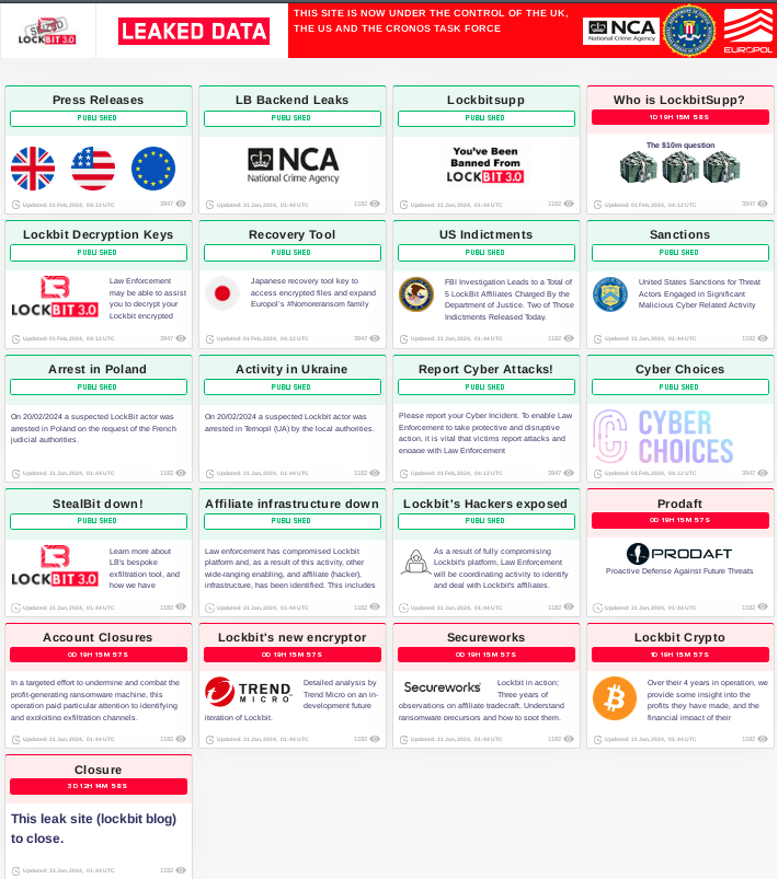

At 9 p.m. GMT, the sites were back online but with a law enforcement agency (LEA) splash page announcing that the sites were now under the control of the UK’s NCA.

On Feb. 20, 2024, the leak site was modified to keep the traditional look of the LockBit website, but instead of its usual content, the site showed a countdown timer — one that has been heavily associated with LockBit — leading to several press releases, indictments, arrests, and blog articles to be released.

Press releases housed on LockBit’s leak site

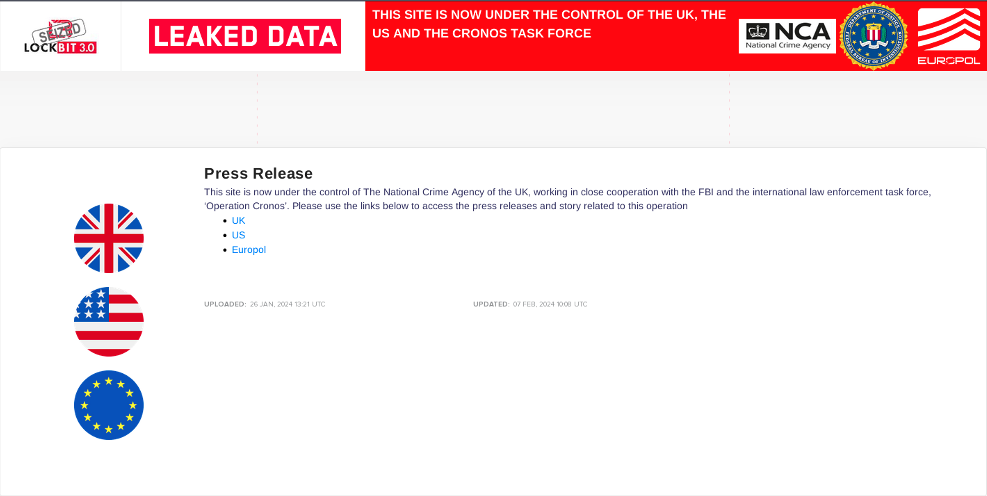

Press releases from the NCA, the FBI, and Europol were made available on the seized leak site, showing the combined efforts of the different agencies in tackling the biggest threats in cybersecurity.

An emphasis was also placed on the use of the word “disruption” rather than the use of “takedown,” which has become synonymous with previous law enforcement actions against criminal organizations. It was clear from the information released throughout the operation that this was not an opportunistic attempt to gain a win against a major cybercrime group. Instead, this was a meticulously planned, well-executed plan that shows how law enforcement agencies have the appetite to go after hard targets — indeed, even groups perceived to be beyond law enforcement’s reach could still be taken on with tangible results.

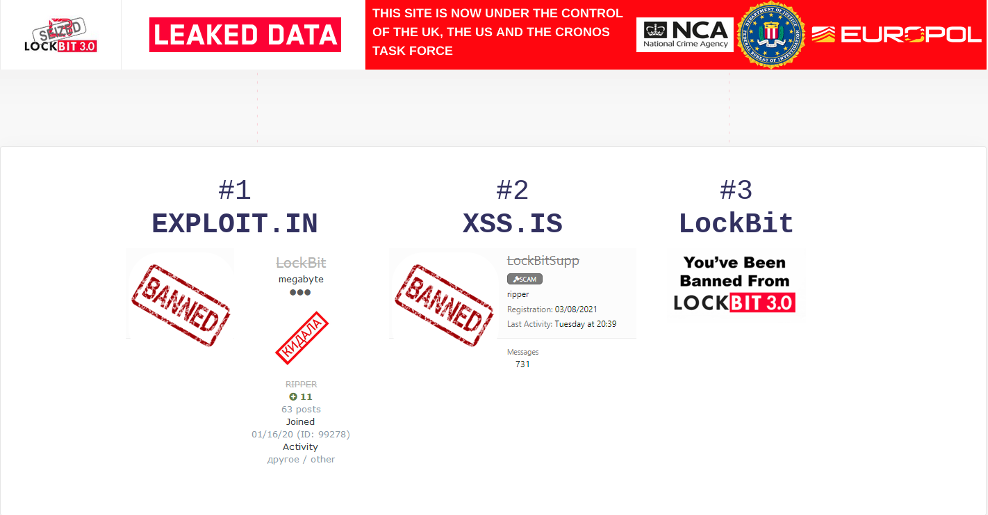

LockBitSupp banned from cybercrime forums

As part of the information released on the leak site, there was a reference to LockBitSupp’s recent status change in Exploit and XSS, two of the most prominent and long-standing cybercrime forums today. LockBitSupp’s recent negative behavior in the criminal community and its resultant ban from these two prominent underground criminal forums also left a negative impact in the cybercrime ecosystem when the operation was publicly announced.

LockBitSupp’s ban also limited its ability to communicate its message in the aftermath of Operation Cronos. Had LockBitSupp maintained access to the forums, the entire LockBit group could have been in a better position to respond to the ongoing commentary and offer reassurance to its affiliates.

Operation Cronos offers LockBit decryption keys

Another key element that sets Operation Cronos apart from traditional site seizures was the announcement that decryption keys would be made available. This offer of support also highlights that ransom payments are not the best course of action. This is further demonstrated by the fact that, contrary to what LockBit claimed in negotiations, victim data was not deleted upon ransom payment.

Trend’s analysis of LockBit-NG-Dev

Trend analyzed a sample that is believed to be an in-development version of a platform-agnostic build that we track as LockBit-NG-Dev, where “NG” stands for “next generation”). Our analysis was published on the seized leak site along with findings from other trusted partners.

The key findings of the analysis revealed that:

- LockBit-NG-Dev is now written in .NET and compiled using CoreRT. When deployed alongside the .NET environment, this allows the code to be more platform-agnostic.

- The code base is completely new in relation to the move to this new language, which means that new security patterns will likely be needed to detect it.

- While it has fewer capabilities compared to LockBit 2.0 (Red) and LockBit 3.0 (Black), these additional features are likely to be added as development continues. However, it’s important to note that as it is, it’s still a functional and powerful piece of ransomware.

- It has removed the self-propagating capabilities and the ability to print ransom notes via the user’s printers.

- The execution now has a validity period that can be seen by checking the current date, which is likely to help the operators assert control over affiliate use and make it harder for security systems to launch automated analysis.

- Similar to LockBit Black, this version still has a configuration that contains flags for routines, a list of processes and service names to terminate, and files and directories to avoid.

- It also still has the ability to rename encrypted files with random file names.

Aside from the technical analysis of the in-development build, our report also outlined the technical issues the group has experienced as well as the apparent decline of LockBit’s reputation.

LockBit back-end leaks reveal victim, affiliate information

If onlookers had any doubt as to whether law enforcement had simply defaced the leak site, this was quickly dispelled when LockBit’s admin panel details were leaked. This leak has made it blatantly obvious to any affiliate that LockBit would no longer be able to operate normally.

The succeeding parts of this section discuss some of the interesting takeaways from the leaked panel screenshots.

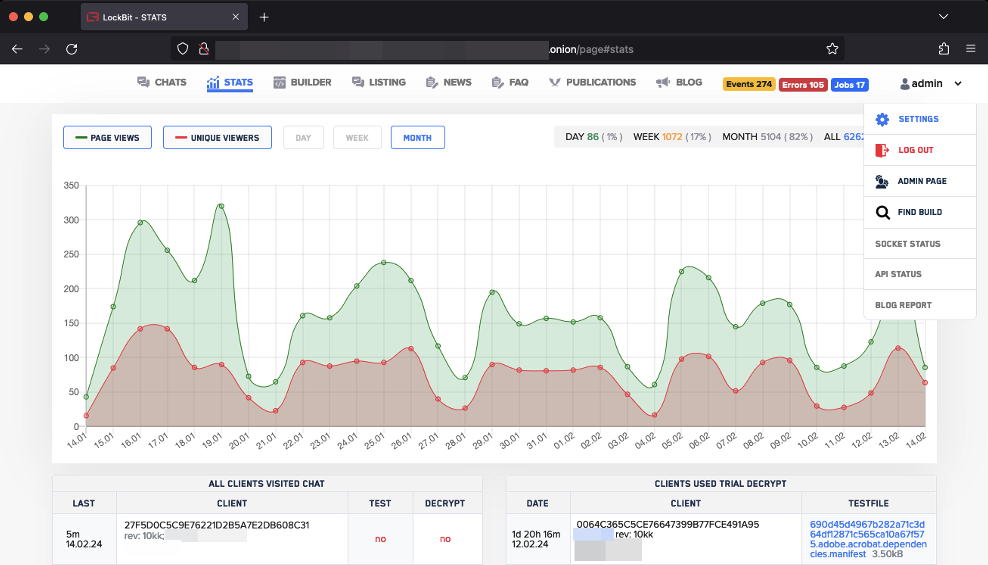

The stats page shows the number of viewers and which victims visited the site and/or decrypted a test file. This was probably used to forecast the likelihood of a victim paying based on their type of engagement with the leak site. It might have also been used to assess if a victim was attracting significant interest, as this is something that could be leveraged in negotiations.

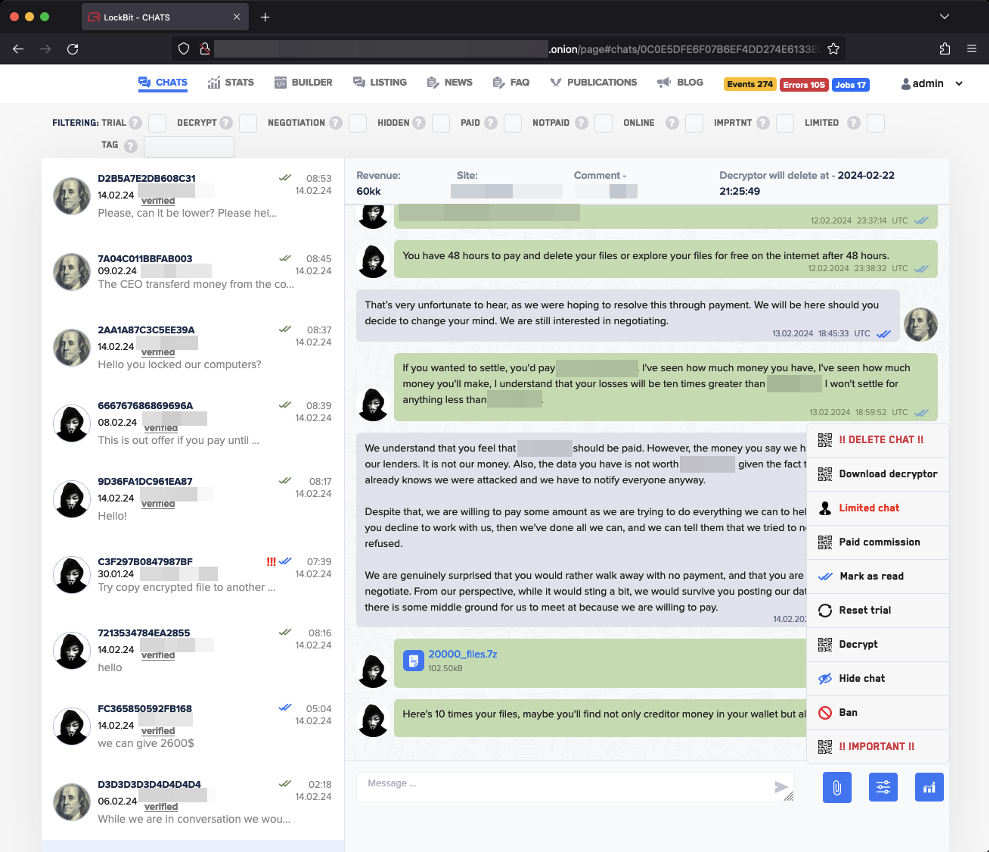

The chats tab revealed that law enforcement had access to conversations between affiliates and victims. This would have helped identify victims and also gauge the true scope of LockBit’s victims. The chat window also had an option for victims to download the decryptor. Any open negotiations or current victims might have been provided this option.

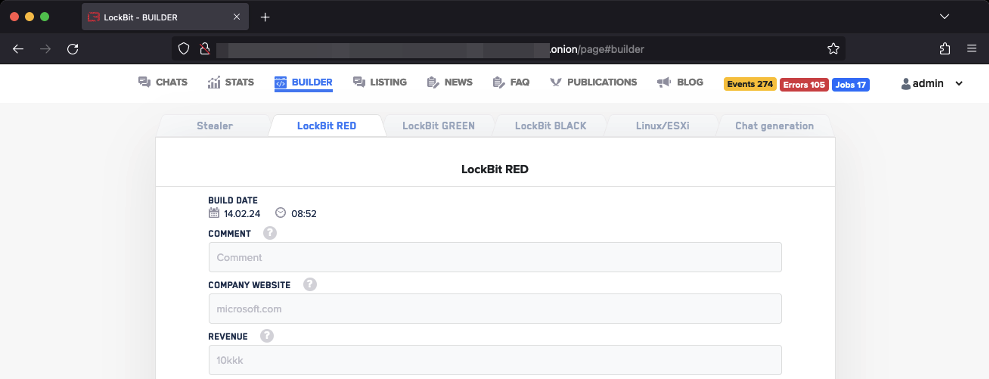

The builder tab confirmed that the group used the colors black, red, and green for the generational builds, as well as a Linux or an ESXi build. The lack of a differently named build suggests the sample we analyzed was definitely not yet in active use.

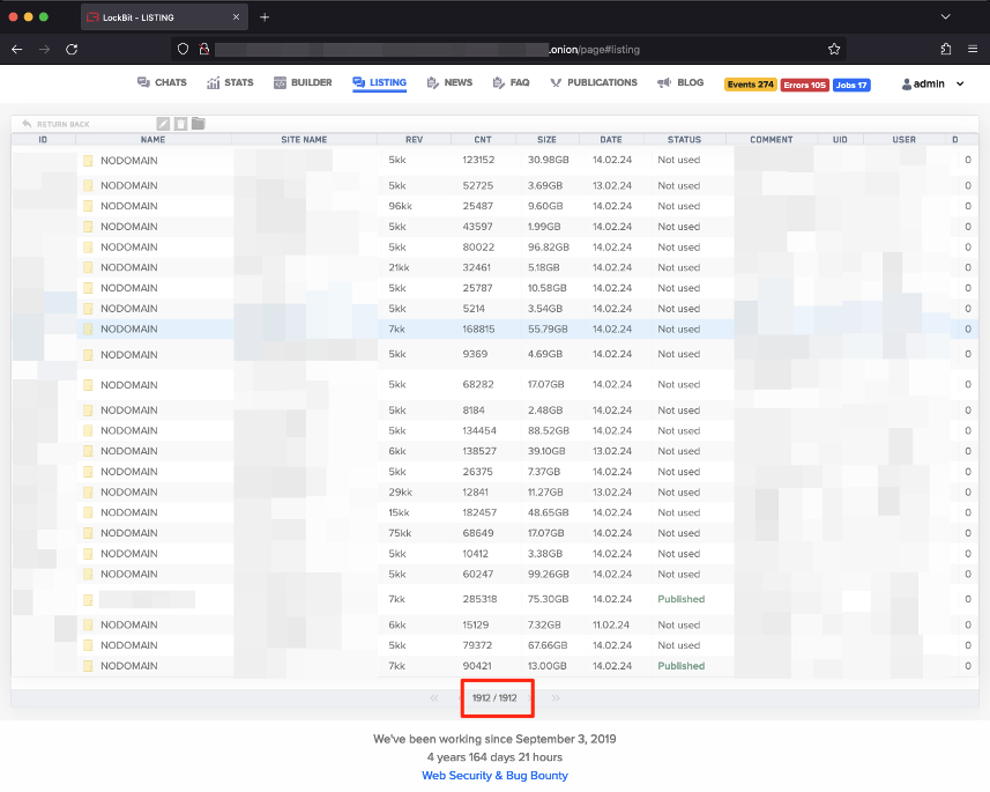

The listing tab shows a table of victims’ names, number of files, revenue, and file size. These pieces of information were likely used for triaging purposes to focus on higher-revenue targets. The number 1912 at the bottom of the page suggests that this was the number of LockBit’s victims at the time the screenshot was taken.

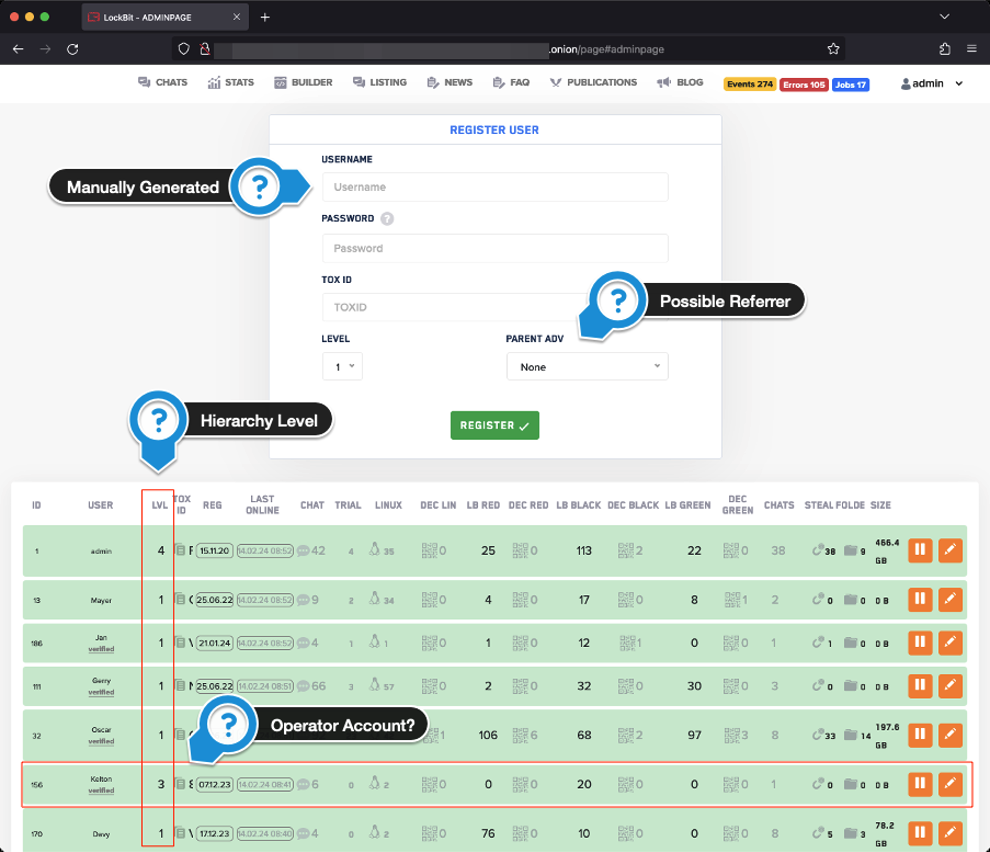

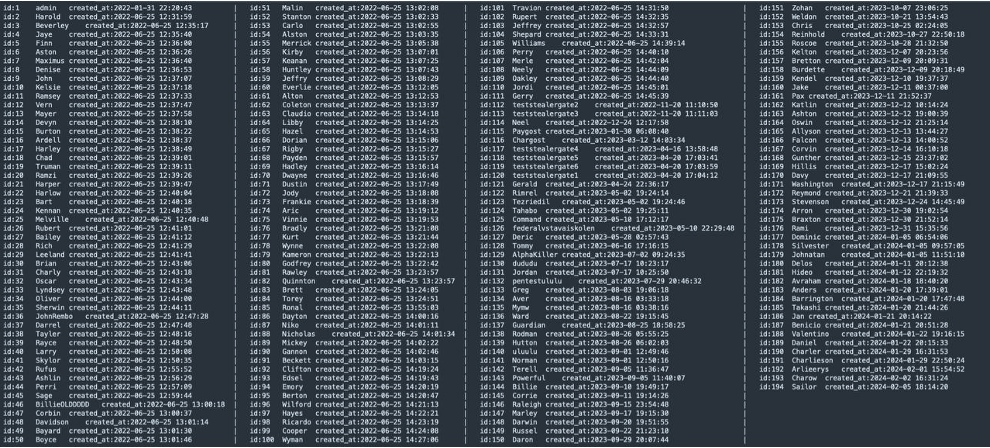

The admin page contains a list of affiliates along with a window showing the information gathered when registering a user. Although affiliate names were believed to be randomly generated, the presence of the username field suggests that usernames can be manually generated in some cases.

There’s also a dropdown for “parent adv”, which suggests that LockBit actors kept a record if a prospective affiliate was referred by an existing affiliate. This was likely used as a way of keeping an audit trail should there be any security issues.

Another interesting item that can be noted in the admin page is the level. LockBit was at Level 4, while its affiliates were at Level 1. The user Kelton was listed at Level 3 even though they had far fewer active chats than some of the other affiliates. This suggests that a member at Level 3 meant that they were either a LockBit operator working directly for LockBitSupp or a very prominent threat actor who was trusted by LockBitSupp.

LockBit affiliates exposed

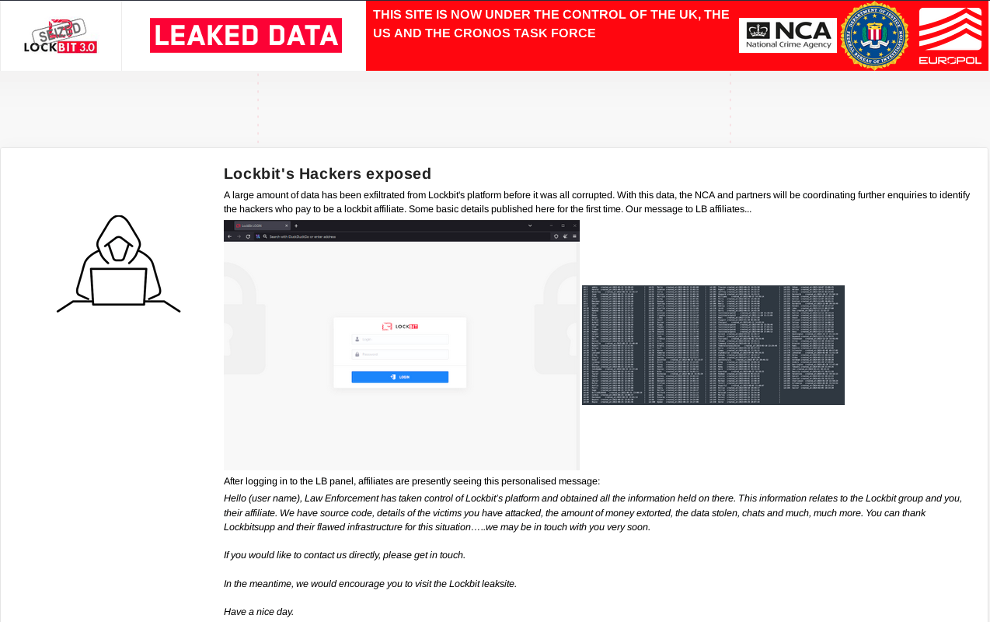

The “Lockbit’s Hackers exposed” section that was published on the leak site revealed that affiliates who logged into their LockBit control panel were greeted with a personalized message informing them that law enforcement had taken control and might be in touch with them.

An examination of the list of affiliates shows that excluding the admin account, there were a total of 193 affiliate accounts. There were also several “testing” accounts seen. We observed that majority of the usernames used are popular first names; this is not at all unique and doesn’t give us much to go on. This also indicates that these usernames are not handles that would typically be reused on forums.

However, there are several interesting usernames that stand out, as well as some that overlap with handles observed to have been used by members of the Conti group:

- Id:5 Finn. This is an alias that was also used by the threat actor Buza (later revealed to be Maksim Rudenskiy following announced sanctions), who was a key member of the TrickBot group and a team lead for coders. This might be a coincidence, but the join time occurred one month after Conti shut down its operations.

- Id:36 JohnRembo. This isn’t your typical first name, so it stands out from the list of affiliates. However, we were not able to find any other notable activity for this moniker.

- Id:46 BillieOLDDDDD. This is another unusual username, but we found no other related activity in our investigations.

- Id:52 Stanton. This is also a handle used by a former crypter for the Conti team.

- Id:112 to 113 and 117 to 120 – teststealergate*. These accounts were probably for internal testing for the Stealc malware.

- Id:126 federalvstavaiskolen. There could be different meanings or translations for this username. One possibility is that if you break it up into separate words (“fed eral vstavai skolen”), it translates to “fed raise from your knees” or “Federal get educated,” depending on the language. This might have been a test account.

- Id:129 AlphaKiller. This is also a peculiar username, but we found no other related activity in our investigations.

- Id: 130, 132, and 140. The accounts dududu, pentestululu, and uluulu are not capitalized like the other names. It’s possible that these are test accounts used by the operators.

- Id: 193 Sailor. “Sailor” is another username that isn’t typical. It’s possible that it’s related to the threat actor that uses the monikers “SailorMorgan” and “cipherpunk”, who has experience working with RaaS groups as a former member of the FiveHands and Yanluowang ransomware groups.

Another notable observation is the large number of affiliates who joined in December 2023. There were 20 affiliates registered in December, which is a significant amount when looking at the other 173 affiliates that joined over the previous 18 months. It is probably a little coincidental that this spike in registrations coincided with the ALPHV (aka AlphaV or BlackCat) outage as a result of law enforcement action. LockBitSupp actively advertised that ALPHV affiliates would be welcome to join.

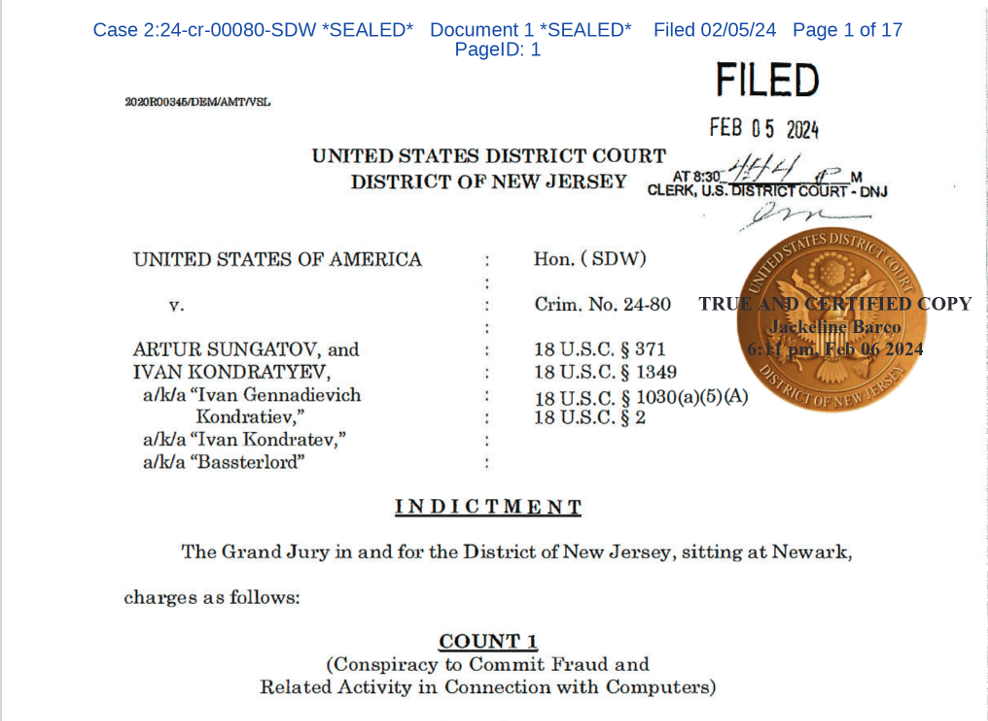

LockBit indictments and arrests

The announcement of indictments against Ivan Kondratyev (Bassterlord) and Artur Sungatov further demonstrated the extent to which law enforcement had gathered information on the LockBit group. In our previous blog entry, we described how we suspected Bassterlord to be the leader of the National Hazard Agency, which is believed to be a major subgroup of LockBit. This indictment targets one of the key members affiliated with LockBit and a prominent member of the cybercrime community.

Underground perspective on LockBit’s disruption

The overall sentiment over LockBit’s disruption seems to fall into one of two groups: The first involves actors who seemed to take some pleasure in the news; this was probably amplified by LockBitSupp’s recent ban from XSS and Exploit forums, as well as the events surrounding it. Meanwhile, the second group includes actors who felt that LockBit would inevitably recover and reform or rebrand.

We monitored underground activity to assess the response to Operation Cronos and identify anyone who might have been involved with the LockBit group. It was expected that given LockBit’s high-profile nature, there would be many online discussions following its disruption. These posts on underground forums might also have caused a few to inadvertently reveal themselves as potential affiliates. There were also plenty of speculations as to whether LockBit would continue as normal. Threat actors were also eager to point out what they would have done differently, which was an added bonus when considering the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) of actors.

The first 24 hours after LockBit’s disruption

As with any major disruption to a service, there was an immediate reaction from both affiliates and other underground threat actors who were casual observers in the hours immediately following the operation.

Two actors in particular published posts on the XSS forum that indicate that they were LockBit affiliates judging by exchanges. An actor using the handle “Desconocido” complained that three ongoing campaigns were affected by the disruption. This comment was also made before the disruption was widely talked about, which gives more weight to the likelihood that the actor was an affiliate. Another actor using the handle “IT-user” announced that LockBit’s Tox account had been seized, which might indicate that prior to that, they were in communication with the actor LockBitSupp. Desconocido revealed that LockBitSupp was already using a secondary account, again implying that they had reason to be in contact with LockBitSupp. In addition, the actor “carnaval”, who is known to be either a current or a former affiliate, was also active on XSS in the conversation regarding the disruption.

A prominent threat actor known as “Bratva” began to highlight to other RaaS groups that CVE-2023-3284 might have been used on both ALPHV and LockBit infrastructures, although this is not mentioned in any law enforcement publications. On the Exploit forum, there was also suspicion raised by the fact that LockBit operators lured affiliates away from ALPHV prior to being infiltrated themselves.

Meanwhile, on the ramp_v2 forum, LockBitSupp, using the “Lockbit” moniker, provided a new Tox ID and announced that the LockBit infrastructure would be rebuilt. LockBitSupp also sought to reassure affiliates that it still had the data intact.

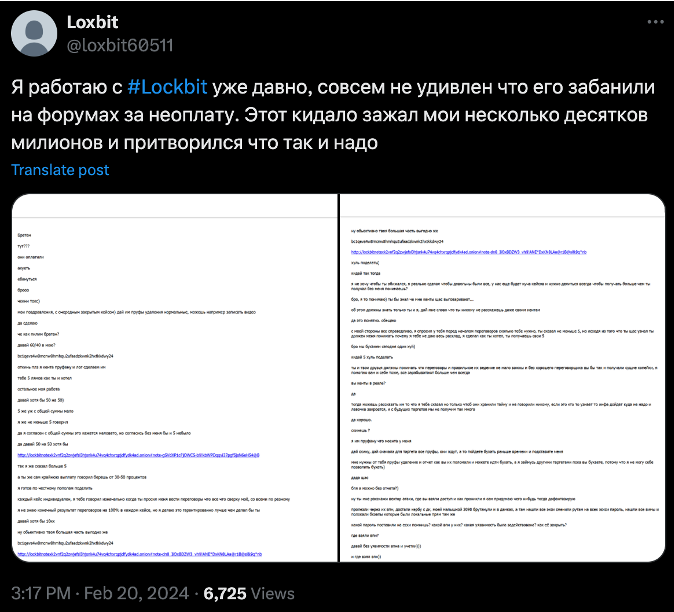

Interestingly, a post on X (formerly Twitter) by a user with the handle “Loxbit” claimed that they had worked as an affiliate and had been cheated by LockBitSupp. In Figure 18, we can see that this same LockBit affiliate uses the handle “Chuck Norris”. We believe it’s possible that this actor also uses the monikers “chak Norris” and “sarg0n”.

The first 72 hours after LockBit’s disruption

In the days following the disruption, the topic was still being widely discussed across underground forums. Members of the forums seemed to appreciate the NCA’s sense of humor, commenting that the law enforcement agency was trying to be “lulzy” (internet slang for comical or amusing) in its actions on LockBit’s leak site. The release of information regarding the arrests also instigated further conversation. There was also a consensus that LockBit would simply rebrand and return, similar to what happened with Conti, Royal, Black Basta, and Hive, although as the rest of the week went by, LockBit’s reputation was further damaged.

On one Breachforums thread that discussed the disruption, one member was of the opinion that LockBit deserved the disruption due to the group targeting hospitals. In the initial days following the disruption, the Exploit and XSS forums seemed to be unusually constrained in their discussion of the topic. The discussion about LockBitSupp’s ban status was active, but the overall discussion pertaining to LockBit’s disruption seemed to be less active than in other forums. One reason for this could have been that as two of the more mature forums in operation, the members of Exploit and XSS might have been under instruction to be wary of researchers and law enforcement monitoring their activity following such a high-profile action.

An interesting observation when looking at the fallout from the disruption is that it sparked some self-reflection among other active RaaS groups. Notably, competitor RaaS groups expressed much interest in learning about how LockBit was infiltrated. A Snatch RaaS operator also pointed out on their Telegram channel that they were all at risk. This is a subtle bonus stemming from the disruption operation: the spread of paranoia in the cybercriminal ecosystem. Other groups are now taking a closer look at what they need to do to reduce the risk of infiltration. Anything that makes operating more difficult is a good thing in the fight against ransomware actors.

In a period that fostered paranoia and introspection, it’s no surprise that members of the criminal underground started to question whether LockBitSupp had collaborated with law enforcement or otherwise. Although there were several mentions of LockBitSupp cooperating with the Federal Security Service (FSB), it’s important to note that this is just speculation and not something we can confirm. The claims were probably bolstered by a Chainalysis report that LockBit group sent donations to a certain “Colonel Cassad” in Donetsk.

Although LockBitSupp was guarded when it came to public communication efforts, which is partly due to its being banned on XSS and Exploit, LockBitSupp attempted to preserve the appearance of being in control of the situation. For example, LockBitSupp responded to the law enforcement countdown that would release information about its identity by doubling the reward to US$20 million. This was a clever move on LockBitSupp’s part, as it seemed to garner support in the criminal underground. The apparent defiance might have also been part of a strategic plan to try to persuade affiliates that the operation was not under threat. In some ways, LockBitSupp appears to have resorted to a PR tactic that many of its own victims were forced to enact following ransomware attacks: LockBitSupp publicly projected a position of strength to its customer base while also internally trying to rebuild and get back to business.

In the first 72 hours, many speculated about the extent of the information to be released about LockBitSupp. There was a lot of build-up leading up to it, which was heightened by the NCA using the infamous LockBit countdown to make the announcement. There was also some confusion in the first few days, with people looking for the official LockBitSupp Telegram channel. This was a result of several accounts masquerading as LockBitSupp. Given the curiosity and media attention generated by the disruption, some actors sought to capitalize on the confusion and take advantage of unwitting victims. For example, a Telegram user with the handle “Lockbit 3.0” claimed to be a LockBit operator and offered positions for affiliates to join the group for a small fee of US$150.

The first week post-LockBit disruption

The much-anticipated leak of information about the threat actor LockBitSupp seemed to have been perceived as anti-climactic in the underground community. Law enforcement’s use of the “Tox Cat” emoji in its announcement, to imply some level of access that it had to LockBit’s operations, was also seen as further trolling from law enforcement. To add, some felt that the lack of details showed that LockBitSupp had called its bluff. However, it was clear that the vague reference to LockBitSupp’s communication with law enforcement did have the desired effect of seeding doubt among some members. Less than an hour after the release of the message pertaining to LockBitSupp talking with law enforcement, some messages on Telegram mentioned that “There’s chatter that Lockbit is a snitch.”

There was also speculation that other groups could now become the market leader, with ALPHV being touted to rise to the top. We now know following the events surrounding ALPHV that this would not be the case.

There was also a discussion about how victim data wasn’t deleted following a payment. It was pointed out that this was no surprise when you consider the value such data would still hold.

As the dust settled following the first few days, there were still a few actors who were focused on how the disruption came about and what its implications were. Some members of the criminal underground undertook their own investigation and began trawling through old posts and dissecting what was said in the past. This further demonstrates the state of paranoia that the disruption instilled.

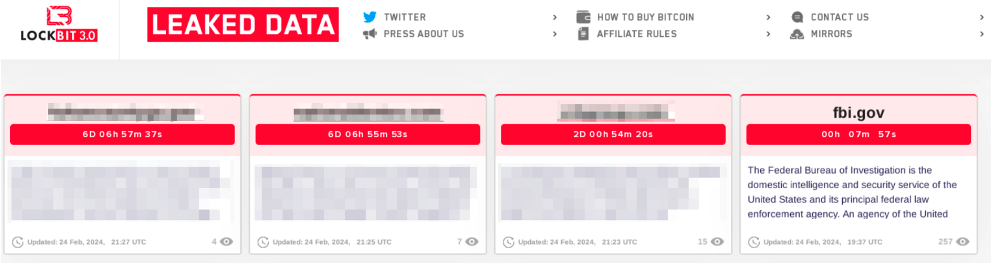

In a rebuttal to law enforcement’s press release, LockBitSupp announced that it will return with new Onion sites on Feb. 24, 2024 and added fbi.gov as the first victim on the new leak site.

When the countdown reached zero, a lengthy statement was released by LockBitSupp. Instead of sensitive FBI data, the new leak site showed a lengthy statement outlining the events and a declaration that it would continue to operate.

LockBitSupp also posted a shoutbox message on the ramp_v2 forum seeking out anyone selling access to .gov, .edu, and .org top-level domains (TLDs), which seemed to have signaled its intent to attack government organizations as a reprisal.

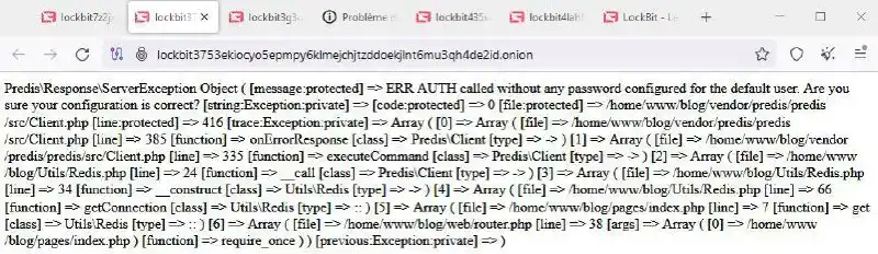

The revival of the leak site appeared to have brought more scrutiny on the LockBit operation. LockBitSupp claimed that its infrastructure had been compromised by law enforcement via a PHP vulnerability, an assertion that many threat actors discussed and echoed in forums. However, this also led to these actors pointing out that the alleged PHP vulnerability was over six months old, calling into question the ability of LockBit operators to secure their environment. This also prompted a closer inspection of the new leak site, after which some were quick to point out that it was still using PHP.

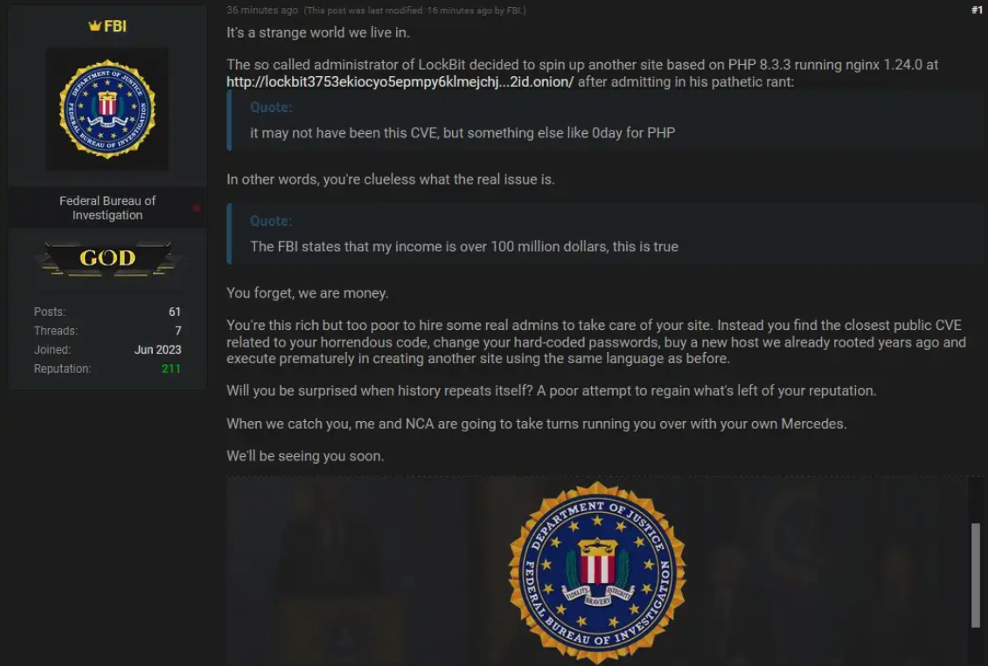

Another forum member using an account that mimicked the FBI recalled how LockBitSupp was looking for an experienced system administrator a year and a half ago.

Another commentator posted a screenshot that suggested LockBitSupp was having authentication issues with one of the new Onion sites.

Similar to the law enforcement leak, there was a lot of interest surrounding the public statement by LockBitSupp on its new leak site. While some saw it as a sign that LockBit operators were back in action, others were a bit more skeptical, with some chat messages discussing how the new leak site is a continuation of the law enforcement operation due to the lack of anything substantial from the FBI leak.

The first two weeks post-LockBit disruption

The return of the LockBit leak site might have been a sign to some that LockBit was back. However, for others, the commotion surrounding the new site didn’t take away from the fact that LockBitSupp got banned from Exploit and XSS. One access broker using the handle “dealfixer” advertised access but specifically mentioned that they did not want to work with anybody from LockBit. There are two possible reasons for this: They were either apprehensive about having any association with a group possibly compromised by law enforcement, or they did not have the desire to work with LockBit following a public complaint by the actor “michon” who alleges that they did not get properly compensated by LockBitSupp.

In the two weeks following Operation Cronos, we observed another arbitration thread against LockBitSupp. This time, another initial access broker going by the moniker “n30n” opened a claim on the ramp_v2 forum due to a loss of payment surrounding the disruption.

Another actor named “SDA” also emerged as a partner and made claims pertaining to LockBitSupp’s existing bans on other cybercrime forums. While the claims were dismissed as an unfortunate side effect of the LockBit disruption, the claims did reveal some chat logs that transpired between the threat actors to confirm their LockBit affiliation. While addressing the claims, LockBitSupp also revealed that it went through all affiliate activity to identify possible infiltrators and removed affiliates who didn’t have ransomware payments from the admin panel. There was also a new deposit requirement in order to become a LockBit affiliate.

While there were a lot of commentaries about how LockBit was back and that the group would come back stronger, evidence to the contrary continued to mount. Interestingly, one user on a Telegram channel belonging to ransomware developers pointed out that LockBit was reposting old victims. We discuss the victims that were posted on the new leak site in a succeeding section that discusses LockBit’s post-disruption activities.

A review of LockBit activity post-Operation Cronos

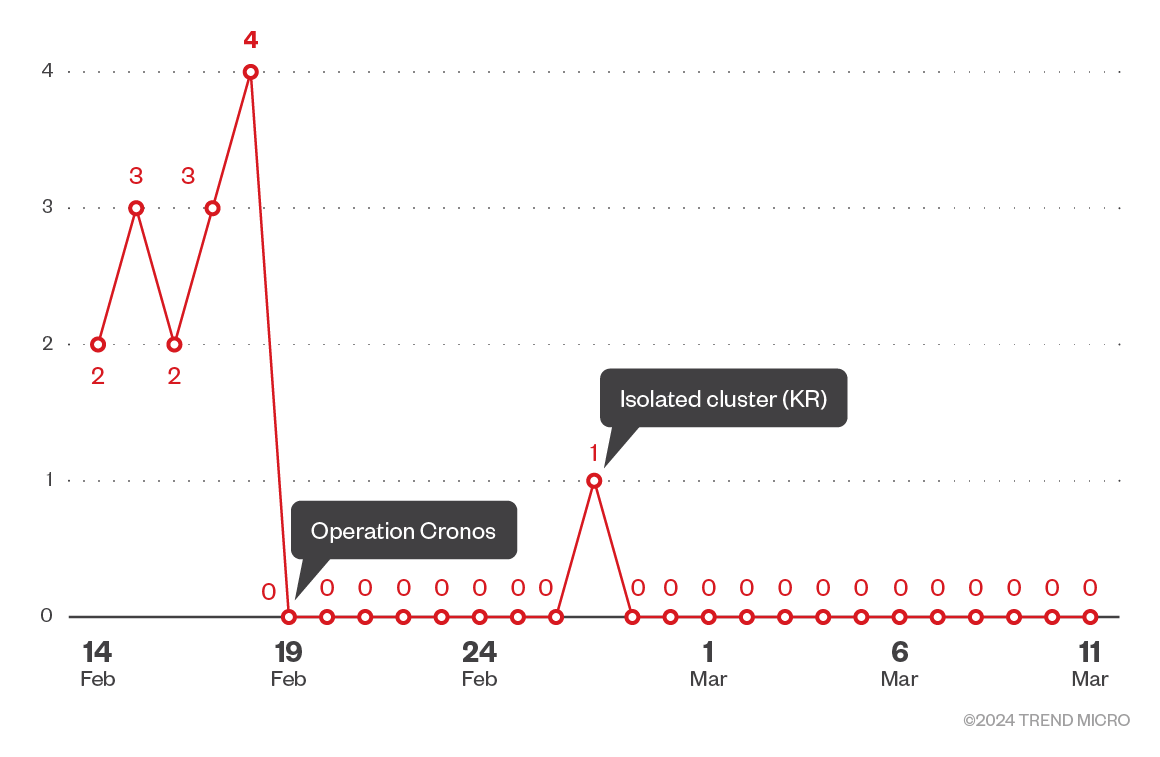

While the disruption operation was ongoing, we continued to monitor our internal telemetry to gauge the impact it had on LockBit infections. Based on our data, there was a clear drop in the number of actual LockBit infections. We excluded threat emulation data and any infections that were a result of the leaked LockBit build. We also used the new Onion sites to track any newly posted attacks and only one small cluster was observed in the three weeks that followed the disruption.

This small cluster occurred on Feb. 27, 2024, when we observed the first indication of a possible LockBit affiliate activity following Operation Cronos. We observed what appeared to be a low-volume campaign targeting South Korea.

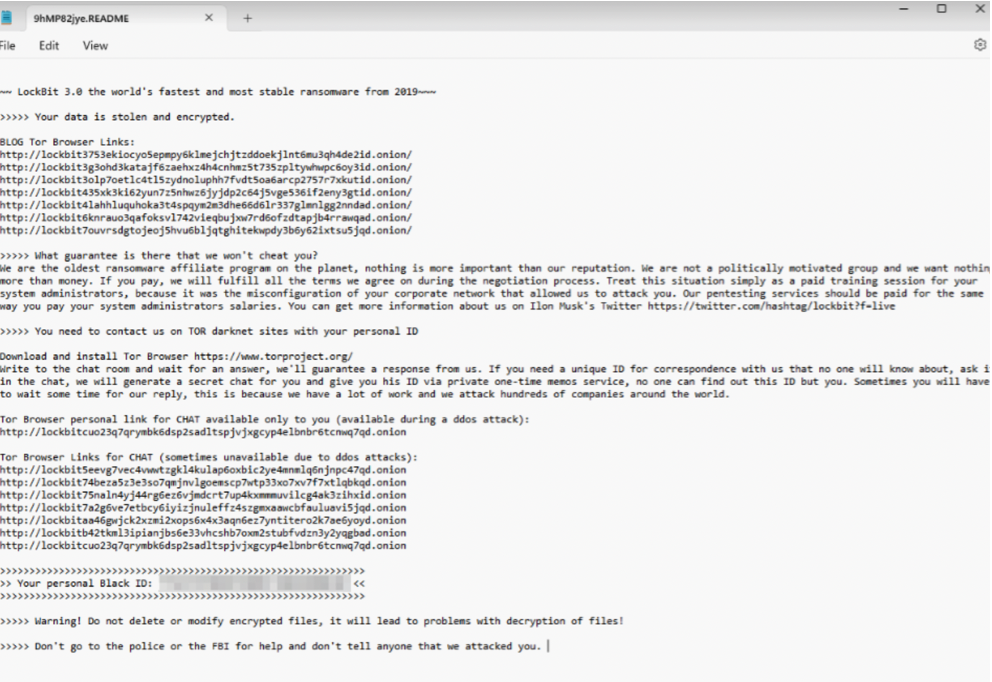

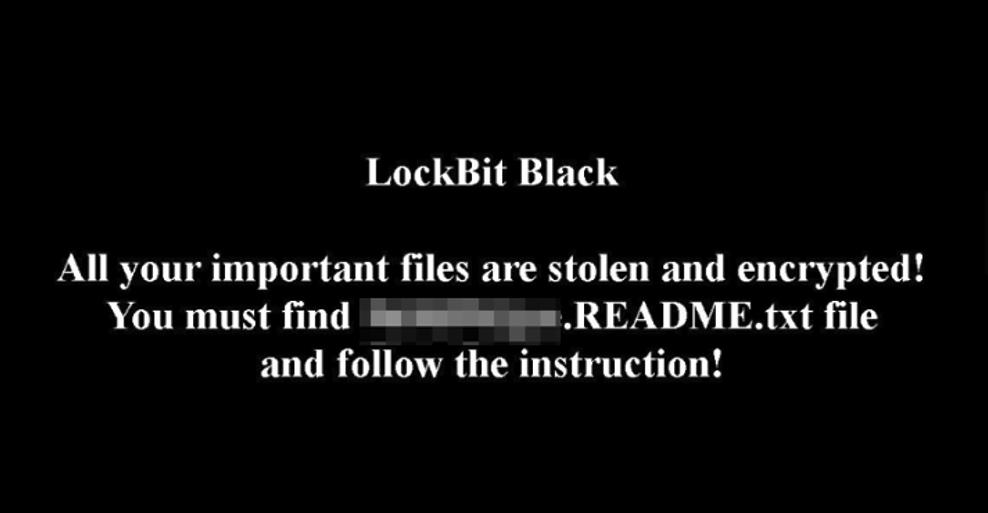

We observed a ransom note containing links to the new LockBit Onion sites (SHA256: 1dab85cf02cf61de30fcda209c8daf15651d649f32996fb9293b71d2f9db46e1).

The infection chain uses a less popular compressed file type, ALZip, which launches the LockBit executable file. ALZip is distributed to victims via email.

Both the ransom note and executable file were submitted to VirusTotal by users in South Korea and are believed to be from two separate attacks. Following further investigation, we were able to identify a successfully blocked detection for the executable in a customer based in Singapore. Although the customer was in Singapore, the extracted attachment’s file name was in Korean.

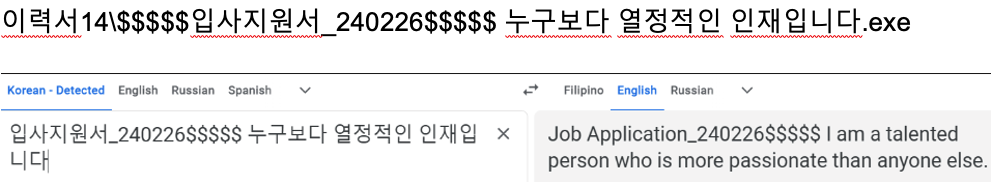

이력서14$$$$$입사지원서_240226$$$$$ 누구보다 열정적인 인재입니다.exe

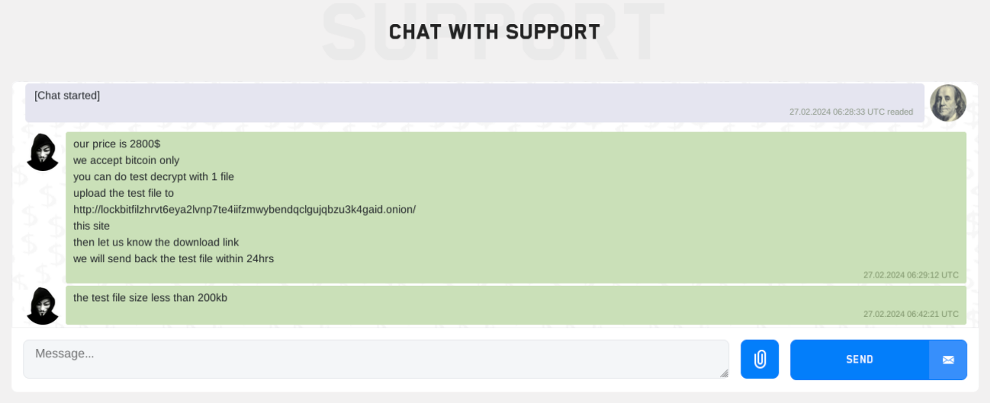

One of the victim conversations from the LockBit chat page shows that the ransom demand was only US$2,800 which is significantly lower than what we would expect for a LockBit negotiation. This could be a minor affiliate desperate to keep some cash flow. If it is LockBitSupp operating alone in an effort to maintain a facade that everything is operating normally, the ransom amount would expectedly be higher, especially since LockBitSupp could post victim information to the leak site.

LockBit breaches post-Operation Cronos

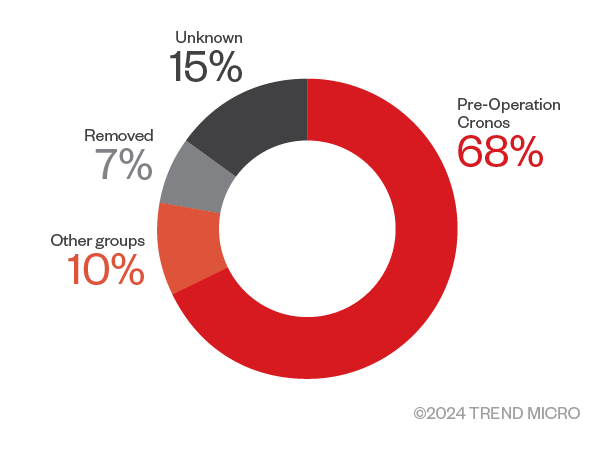

Following the disruption operation, there was much discussion about whether or not LockBit would be able to weather the storm and continue to operate. On the surface, it would appear that LockBit is operating like it had before the disruption, but an examination of the leak site victims and its results paint a very different picture. As of this writing, 95 victims were posted to the leak site after Operation Cronos.

By checking previous LockBit posts and the timestamps on leaked data, the following are some highlights of what we’ve uncovered in our investigation:

- Over two-thirds of the victims were reuploaded and the attacks on these victims occurred prior to Operation Cronos.

- In the middle of March 2024, we observed that victims being posted to the LockBit leak site were recently posted by other groups — the majority were ALPHV victims, while one was a RansomHub victim.

- Seven victims were removed before we could confirm when the attacks were likely to have been carried out.

- 14 victims were still not published and we did not find any public data other than the posts on the LockBit site that claim to verify the actual attack dates.

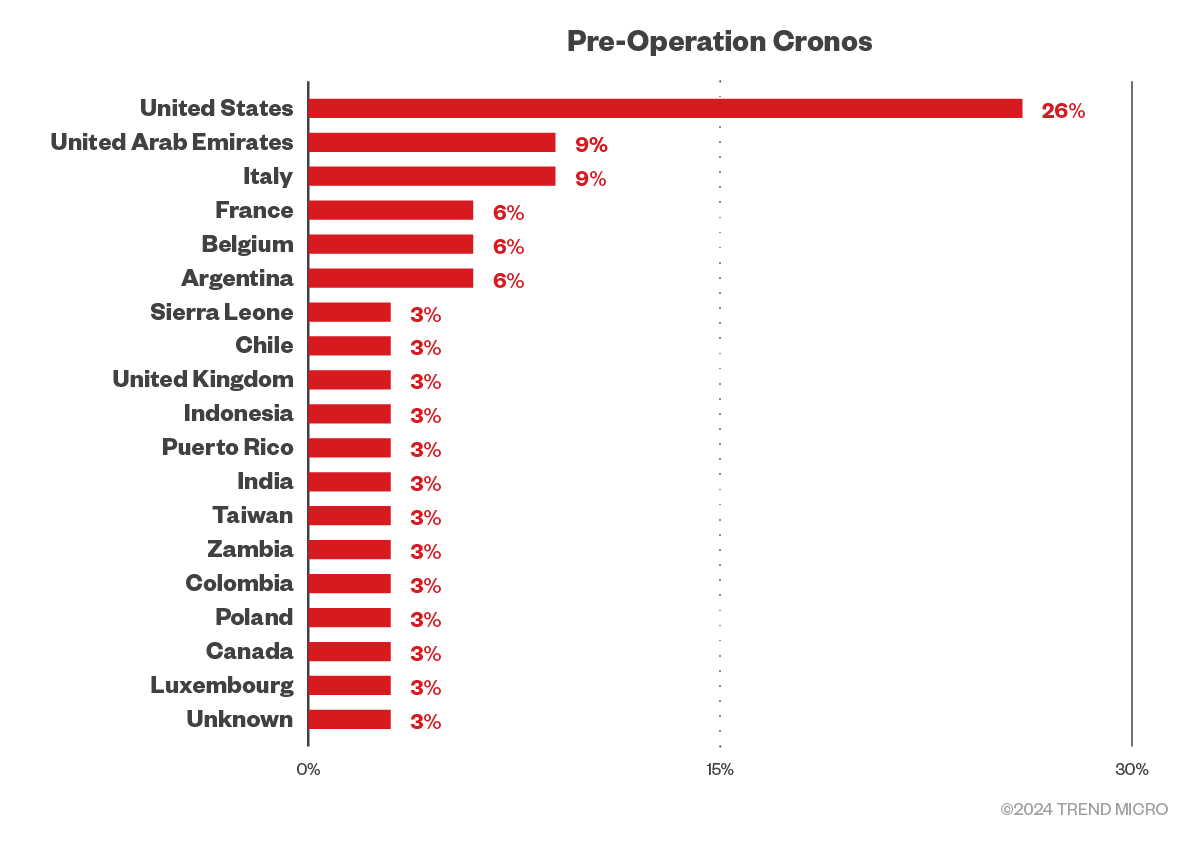

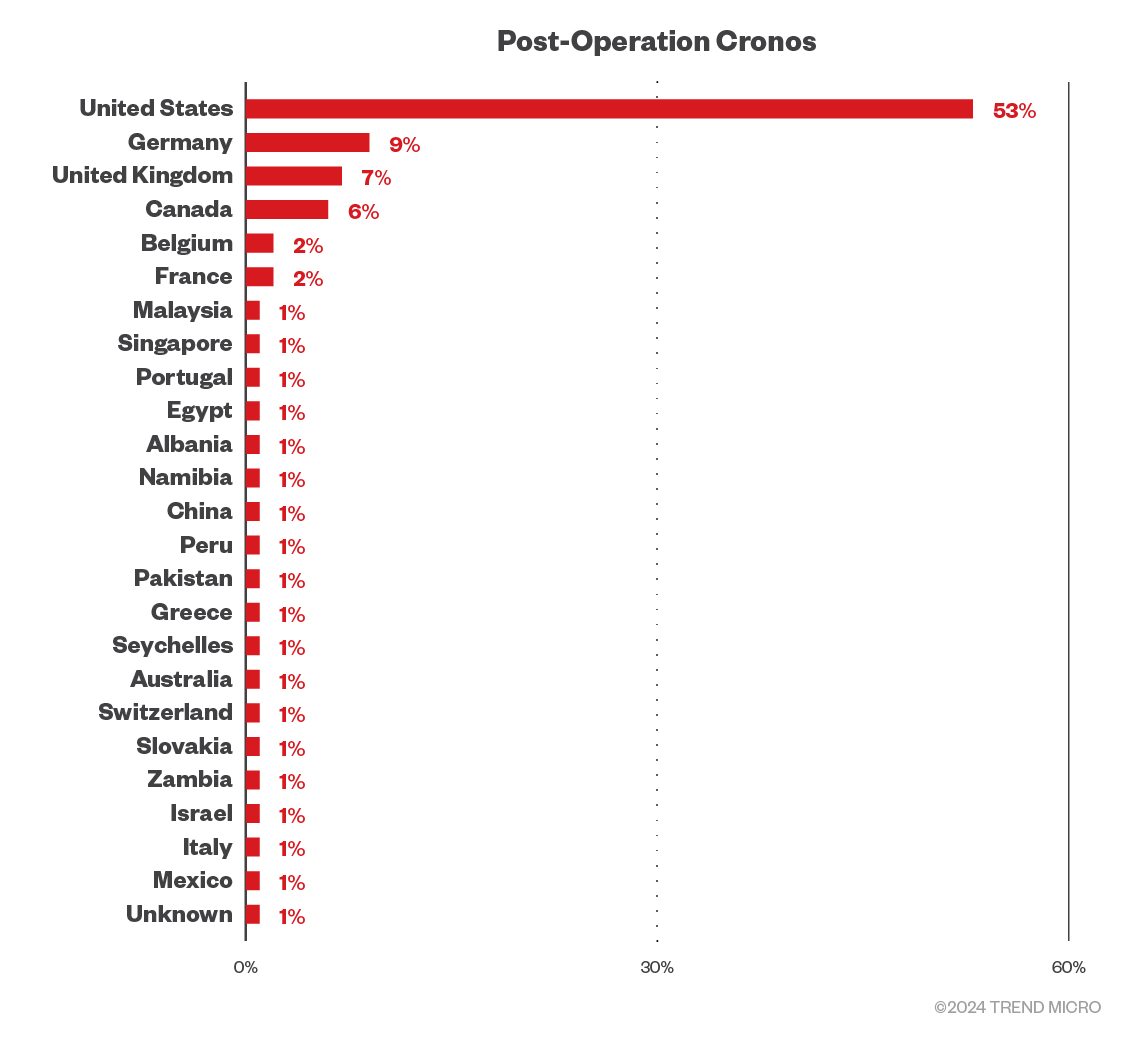

Another interesting observation is the distribution of countries after the disruption compared to normal LockBit operations. Following the operation, LockBitSupp appears to be attempting to inflate the apparent victim count while also focusing on posting victims from countries whose law enforcement agencies participated in the disruption. This is possibly an attempt to reinforce the narrative that it would come back stronger and target those responsible for its disruption.

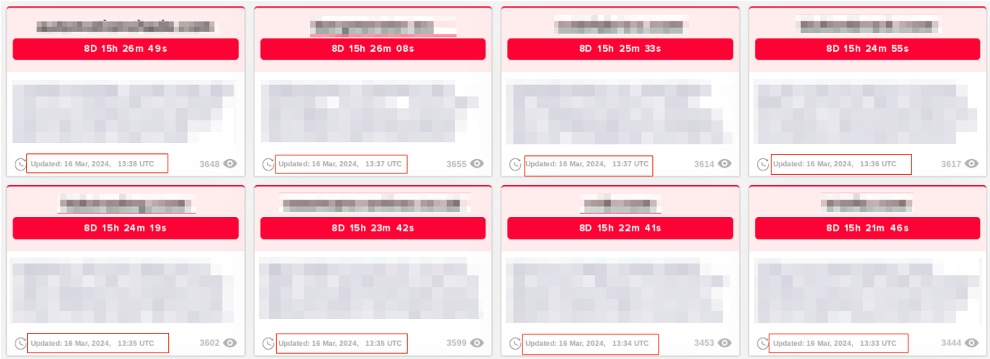

Further bolstering the hypothesis that the leak site is being manipulated to give an appearance of normalcy is the addition of victims in batches, which indicates one person is maintaining it. This is far from how normal affiliates would typically behave.

There’s also the removal of some victims, just as the countdown timer is about to end. It could be argued that this is a result of victim payment. However, when taking everything into account, it could also be another method of inflating numbers as there is no proof without leaked data.

When examining the leaked data for victims that weren’t previously posted on the old leak site, it was evident that the file tree was modified to make it look like it was updated recently. However, the remainder of the dates might reflect the true date.

Forecasting the future of LockBit

With Operation Cronos, we saw a new approach to combatting ransomware. Disrupting and undermining the business model seem to have had a far more cumulative effect than executing a technical takedown. And while LockBitSupp was not part of the cohort of people arrested, affiliates will likely consider all the publicly available information and opt to work for other groups; or better yet, they might reconsider if ransomware is too high-risk of a venture.

There is a valuable lesson to be gained from Operation Cronos. This modern approach to tackling cybercrime shows how powerful collaboration among multiple law enforcement agencies, cooperation between trusted partners in the industry, and arguably the most important factor — patience — can be in thwarting high-profile cybercrime groups. Had law enforcement gone for the traditional takedown approach, we would have likely seen a rapid recovery from the group. In its spearheading of this new multilayered disruption approach, the NCA and its partners have a set a new standard on how such operations can be carried out in the future.

Before we declare that LockBit is completely gone, we should look back on previous law enforcement operations and consider whether a month is enough time to make that assessment. Other high-profile operations, such as the Emotet and Qakbot takedowns, were also very successful in the short term. However, after a few months they re-emerged. It’s important to note that comparing botnets and loaders with RaaS groups isn’t quite the same. With botnets and loaders, the product speaks for itself and if it stands out as something that will deliver, then threat actors will flock back to buy it. With RaaS groups, there’s a bit more at stake when attempting to rebuild. Reputation and trust are key to attracting affiliates, and when these are lost, it’s harder to get people to return. That’s probably why we see groups rebranding rather than re-emerging under the same name. Another factor is the sheer availability of other groups to join.

While it is true that in its inception, LockBit led the way and proved innovative compared to its peers, Operation Cronos succeeded in striking against one element of its business that was most important: its brand.

The playing field is a lot more level now, and with the stagnation of the LockBit brand last year, followed by further reputational damage caused by this operation, affiliates must be seriously asking themselves if it would be worth the risk to return to a previously compromised operation.

Source: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/24/d/operation-cronos-aftermath.html

“An interesting youtube video that may be related to the article above”

Views: 0