Executive Summary

- On January 17, the BlackCat ransomware group added an entry for an electronic health record (EHR) vendor to its extortion site., Bbut, as of January 21, the vendor’s entry no longer appeared there.

- Following the claim, the SecurityScorecard Threat Research, Intelligence, Knowledge, and Engagement (STRIKE) Team investigated the incident.

- By pairing its exclusive access to traffic data with public reporting on BlackCat’s tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), STRIKE identified possible evidence of BlackCat-affiliated activity on target IP addresses.

- This evidence may reflect the use of the BlackCat group’s exfiltration tool, ExMatter/Fendr, on the vendor’s systems but suggests that the scope of the activity was relatively limited.

Background

On January 17, the BlackCat ransomware group added an entry for a major U.S. electronic health record (EHR) vendor to its extortion site.

Image 1: BlackCat added an entry for an EHR vendor to its data leak site on January 17 (source: DataBreaches.net).

On January 19, the vendor responded to these claims, reporting that they had observed no evidence that attackers had accessed customer data but noting that an investigation was ongoing. As of January 21, the vendor’s entry no longer appeared on BlackCat’s data leak site.

The BlackCat ransomware-as-a-service operation, also known as ALPHV, first surfaced in November 2021. It is widely understood to be a successor to the BlackMatter operation, which succeeded the DarkSide ransomware group and achieved widespread notoriety for its role in the Colonial Pipeline attack.

Since its appearance, the group has targeted U.S. organizations particularly heavily, including local governments and educational institutions. Although a spokesperson for BlackCat has declared that the group would not target medical institutions, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) identified BlackCat as a threat to the health sector on January 12.

Findings: Suspicious Traffic to Remote Access Service

When collecting traffic data for the affected organization, STRIKE researchers created a query dedicated to sampling traffic involving the IP addresses where remote access services appeared to be in use. Previous research has noted that BlackCat affiliates have sometimes leveraged compromised credentials to use remote access services for initial access to target organizations. STRIKE identified three vendor subdomains that suggested the use of such services and then collected traffic data involving the IP addresses hosting those subdomains to identify communications that may suggest attempts to compromise these services.

Between November 26 and January 17, forty-five unique IP addresses communicated with the two IP vendor addresses hosting remote access services. Of those, the vendors contributing to VirusTotal detected twenty-seven as malicious. One of these, 195.176.3[.]23, may be particularly likely to have been involved in an initial access attempt. It and a target company IP address communicated on December 3.

Members of the VirusTotal community have identified 195.176.3[.]23 as a TOR exit node and observed it in recent credential-stuffing attacks. In general, it is common for threat actors to use TOR to conceal the origins of their traffic. Still, this IP address’s recent involvement in credential-stuffing is particularly noteworthy, given that that is a tactic BlackCat affiliates have employed in previous attempts to access remote services.

Findings: Additional Traffic Data

In addition to the traffic to remote access services, researchers also collected a wider sample of traffic to and from all the IP addresses where SecurityScorecard’s ratings platform observed issues affecting the target organization’s security. Researchers consulted this traffic sample to identify other suspicious traffic that may reflect BlackCat activity leading up to and following suspicious communication with the remote access service on December 3.

Findings: Possible Reconnaissance

As a hypothesis accompanying the one that the suspicious traffic to the remote access service involved an attempt to authenticate it using compromised credentials, STRIKE investigated traffic from the weeks leading up to December 3 to identify evidence of possible reconnaissance that could have facilitated that access attempt.

Attackers could have acquired credentials through phishing or by infecting an employee device with information-stealing malware. Researchers sought out traffic that may reflect such activity. Between November 19 (the first day traffic data was available) and December 3, vendor-attributed IP addresses communicated with 374 unique IP addresses, of which cybersecurity vendors have linked 120 to malicious activity.

Much of the data involving these IP addresses indicates short, one-off transfers of small amounts of data, which likely reflects low-level scanning and probing activity unrelated to the claimed attack.

However, researchers did identify twelve IP addresses engaged in repeated communication with the vendor network, which may reflect more sustained malicious activity that enabled later stages of the attack. These IP addresses are available in an appendix below.

Findings: Traffic Data Suggesting Use of ExMatter

While reviewing the traffic data they collected, STRIKE researchers observed evidence that may reflect the deployment, or attempted deployment, of the BlackCat group’s exfiltration tool (ExMatter/Fendr) on the vendor’s network.

Previous research into ExMatter has found that it hosted most of its command and control (C2) infrastructure on DigitalOcean IP addresses and exfiltrates data to a remote server over port 22. Knowing this, STRIKE first filtered its traffic sample by port, identifying 957 flows over port 22. These involved 404 IP addresses from outside the vendor’s network. A majority (341) of those IP addresses belong to Digital Ocean.

Researchers then consulted SecurityScorecard’s Attack Surface Intelligence (ASI) tool to identify the DigitalOcean IP addresses capable of acting as a remote server. Those IP addresses would have port 22 open (or a similar port running SSH services, such as ports 2222 and 8222) was open, suggesting that the IP address could have been used to establish a tunnel with the vendor IP addresses involved in this traffic over port 22. ASI revealed port 22, 2222, or 8222 to be open at 328 of the 341 DigitalOcean IP addresses, suggesting they were possible exfiltration destinations.

ASI additionally revealed that port 22 was open at both vendor-attributed IP addresses involved in this traffic, which indicates that exfiltration from port 22 of those IP addresses would be feasible. This bears noting because it may help differentiate this traffic from scanning, which can often attempt to contact IP addresses at port 22, even when it is closed, simply to identify IP addresses where it is open.

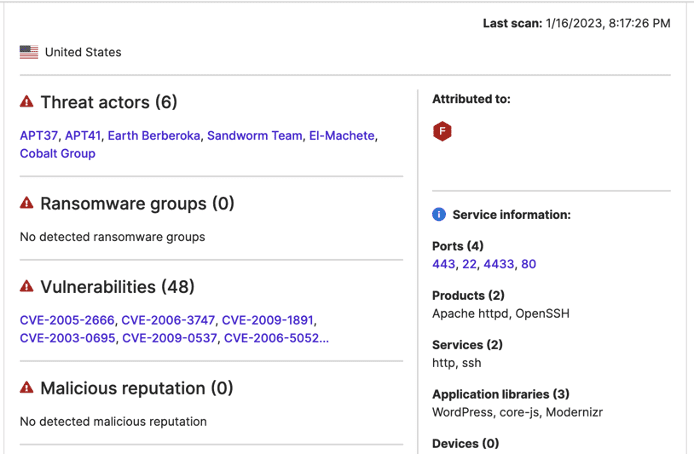

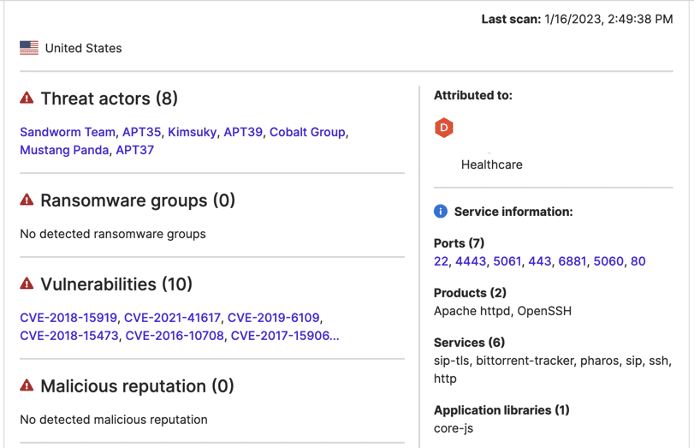

Images 2-3: ASI found port 22 to be open, and vendor IP addresses were observed communicating with suspicious external IP addresses.

Of 404 IP addresses communicating with vendor assets over port 22, 341 belong to DigitalOcean. Of those, ASI found port 22 (or similar ports running SSH services, such as ports 2222 and 8222) to be open at 328, suggesting that they could have been used to establish a tunnel with port 22 of the vendor IP addresses involved in this traffic.

Conclusion

While the traffic data may reflect the use of ExMatter on the vendor’s systems, this traffic constitutes a comparatively small portion of the total traffic sample. The relatively low traffic volume may therefore indicate either that the group’s exfiltration attempts were unsuccessful or that they resulted in the theft of a relatively small amount of data.

As of January 21, the affected vendor claims not to have observed evidence that the attackers exfiltrated client data and the company’s entry no longer appears on BlackCat’s breach site, which raises three possibilities: that negotiations are ongoing, successfully concluded, or that the group’s claim was false or exaggerated and that it has retracted it when confronted with this fact.

While BlackCat does not have as prominent a public record of making false or exaggerated claims as other ransomware groups, it would not be unheard of for a threat actor to assert that a breach was more significant than it actually was. While some data available to SecurityScorecard suggests activity resembling previous BlackCat TTPs, it does not necessarily indicate the successful encryption or exfiltration of data from the target organization. It may, however, help inform future efforts to defend against BlackCat and other ransomware operations by identifying assets those groups may use, like the suspicious IP addresses listed in the appendices below.