In 2021, Kaspersky ICS CERT experts noticed a growing number of anomalous spyware attacks infecting ICS computers across the globe.

Although the malware used in these attacks belongs to well-known commodity spyware families, these attacks stand out from the mainstream due to a very limited number of targets in each attack and a very short lifetime of each malicious sample.

By the time the anomaly was detected, this had become a trend: around 21.2% of all spyware samples blocked on ICS computers worldwide in H1 2021 were part of this new limited-scope short-lifetime attack series and, at the same time, and, depending on the region, up to one-sixth of all computers attacked with spyware were hit using this tactic.

In the process of researching the anomaly, we noticed a large set of campaigns that spread from one industrial enterprise to another via hard-to-detect phishing emails disguised as the victim organizations’ correspondence and abusing their corporate email systems to attack through the contact lists of compromised mailboxes.

Overall, we have identified over 2,000 corporate email accounts belonging to industrial companies abused as next-attack C2 servers as a result of successful malicious operations of this type. Many more (over 7,000 in our estimation) have been stolen and sold on the web or abused in other ways.

The full report is available on the Kaspersky Threat Intelligence portal.

For more information please contact: ics-cert@kaspersky.com.

“Anomalous” spyware attacks

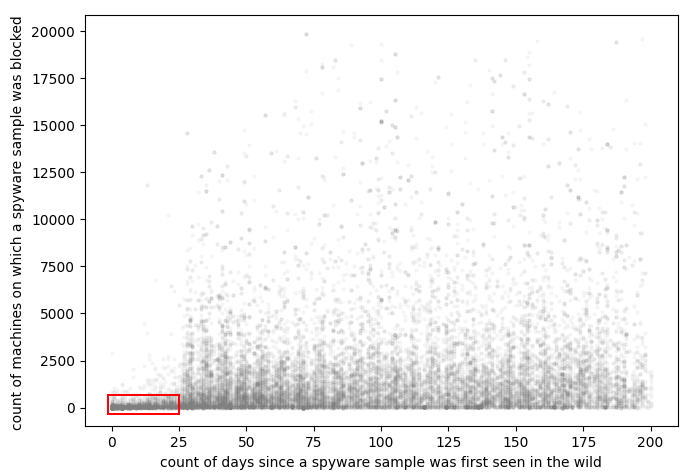

In 2021, we noticed a curious anomaly in statistics on spyware threats blocked on ICS computers. An analysis of 58,586 samples blocked in H1 2021 revealed that 12,420 (around 21.2%) of these samples had a sufficiently limited scope (i.e., the total number of machines on which a sample was blocked, including non-ICS related computers) and short lifespan (i.e., the number of days between the first and last sample detection dates), as shown in the red rectangle on the chart below. It can be seen that the lifespan of the selected “anomalous” attacks is limited to about 25 days. And at the same time, the number of attacked computers is less than 100, of which 40-45% are ICS machines, while the rest are part of the same organizations’ IT infrastructure.

Although each of these “anomalous” spyware samples is very short-lived and is not widely distributed, they account for a disproportionately large share of all spyware attacks.

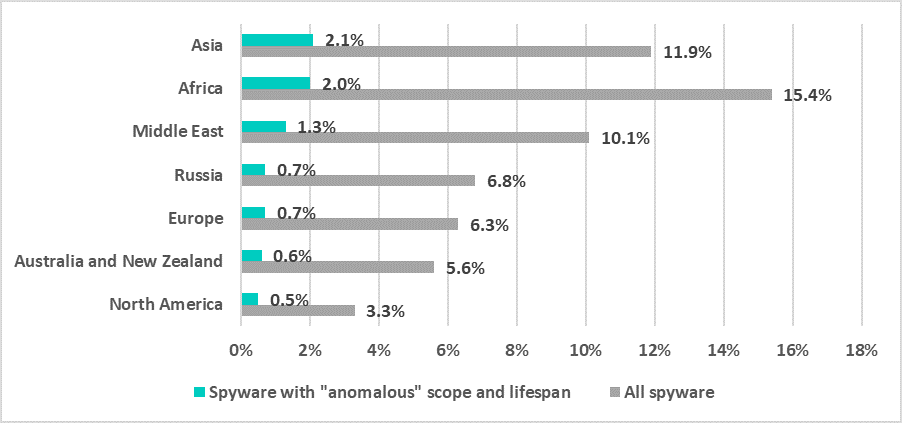

In Asia, for example, every sixth computer attacked with spyware was hit with one of the “anomalous” spyware samples (2.1% out of 11.9%, as shown on the graph below).

In Africa (2% out of 15.4%), the Middle East (1.3% out of 10.1%), Europe (0.7% out of 6.3%), Russia (0.7% out of 6.8%), Australia and New Zealand (0.6% out of 5.6%), and North America (0.5% out of 3.3%), about one spyware attack in ten involved one of the “anomalous” spyware samples.

It seems that the ecosystem of commercial spyware attacks has launched a new and rapidly evolving series of campaigns, shrinking the size of each attack and limiting the use of each malware sample by quickly enforcing its replacement with a fresh-built one.

all spyware threats vs. “anomalous” samples

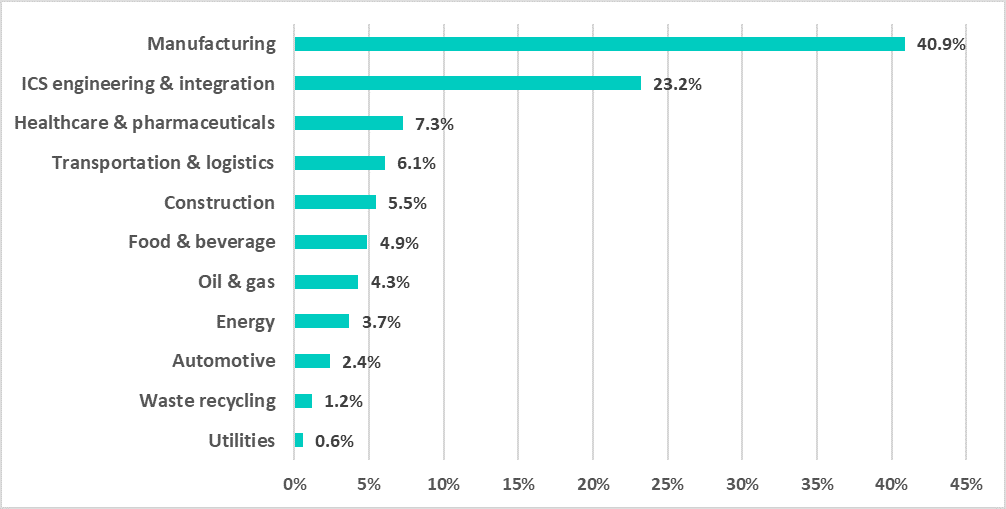

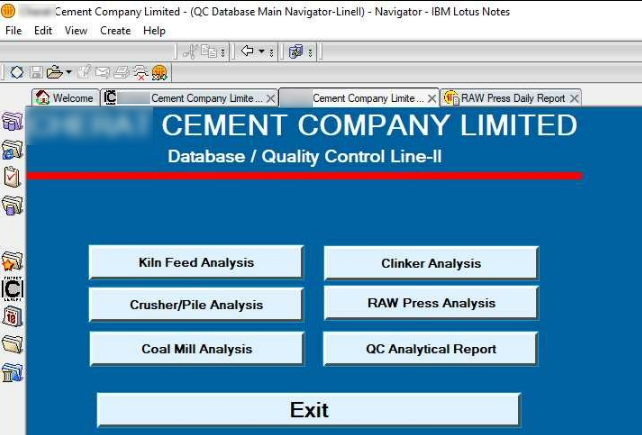

Notably, the majority of ICS computers on which “anomalous” spyware samples were blocked in H1 2021 were from the manufacturing and ICS engineering & integration industries. We believe this skew in data was due to the nature of these “anomalous” attacks, which is described in the “C2 infrastructure” section of this report.

in H1 2021 by industry

Spyware analysis

As regards the spyware samples used in “anomalous” attacks on ICS computers in H1 2021, these are all the same breeds of commodity spyware such as Agent Tesla/Origin Logger, HawkEye, Noon/Formbook, Masslogger, Snake Keylogger, Azorult, Lokibot, etc.

As normal, most of the spyware samples blocked had multiple layers of obfuscation folded one into another. The technique is essentially based on hiding binary code into the resources of an application. For example, one of the popular implementations involved encoding a binary into an image using RGBA (Red, Green, Blue, and Alpha channels) to store bytes.

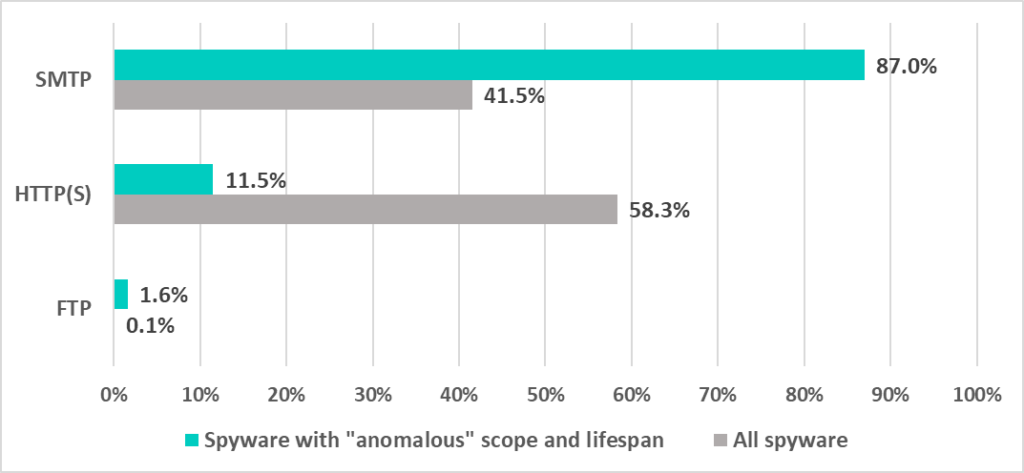

As we discovered, the only significant difference between generic and anomalous spyware samples was the types of C2 infrastructure used.

C2 infrastructure

Unlike generic spyware, the majority of “anomalous” samples were configured to use SMTP-based (rather than FTP or HTTP(s)) C2s as a one-way communication channel, which means that was planned solely for theft.

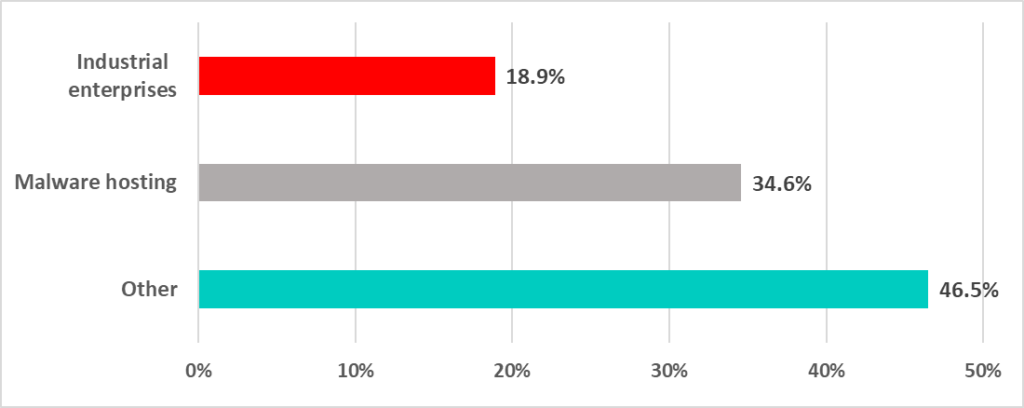

About 18.9% of all “anomalous” spyware was configured to connect to a server owned by some victim industrial enterprise.

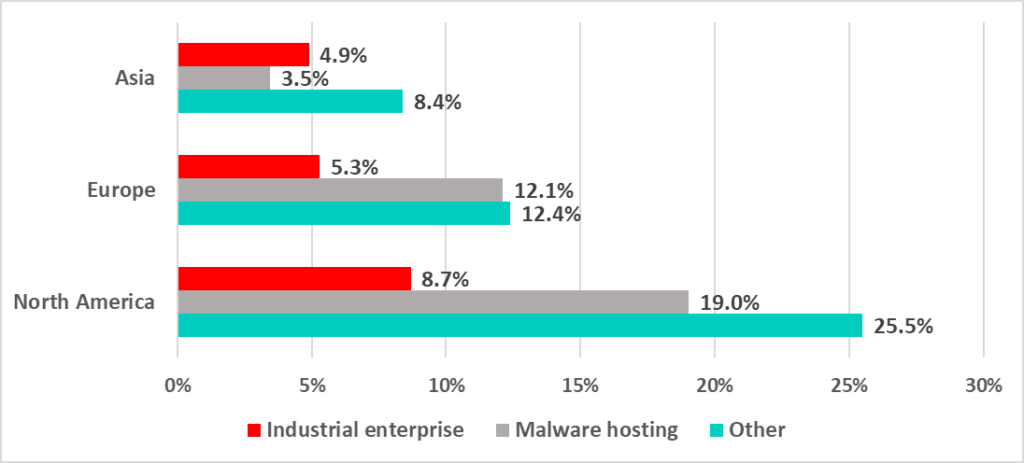

Almost all (99.8%) of the C2 servers found in the configuration of “anomalous” spyware samples were deployed in just three regions – Asia, Europe, and North America.

We also noticed that the majority of C2s, including those deployed on abused infrastructure owned by industrial companies, were deployed on servers in North America.

That was an unexpected finding since 34.6% of attacked ICS computers belong to Asian companies. But the analysis revealed that a surprisingly large number of mid-size industrial companies in Asia have their public-access infrastructure, such as DNS, corporate web and email servers, hosted on North American rather than Asian servers (rented directly from North American providers or from various Asian providers that in fact “provide” infrastructure made available to them by North American providers).

Tactics, techniques, and procedures

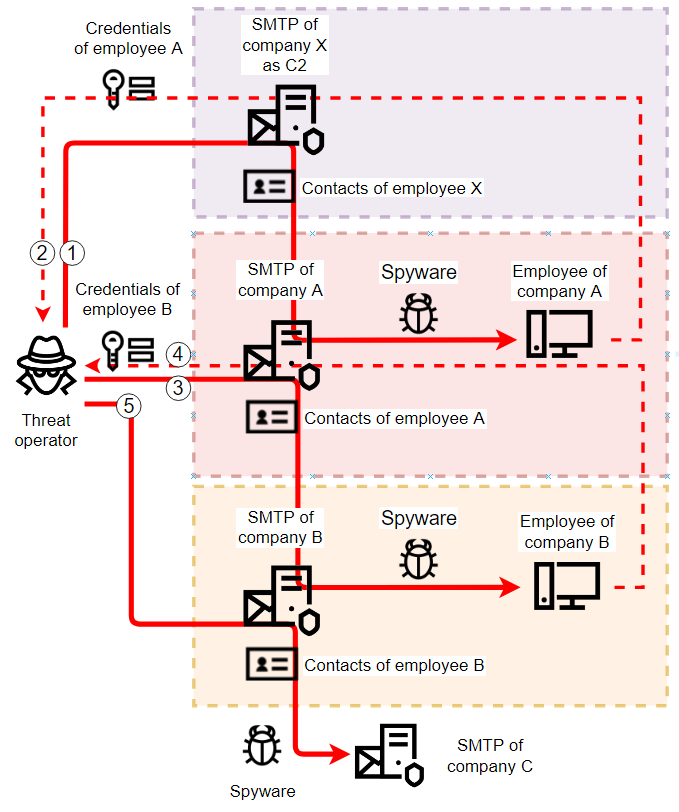

We believe that initially stolen data is used by threat operators primarily to spread the attack inside the local network of the attacked organization (via phishing emails) and to attack other organizations in order to collect more credentials.

An analysis of source and destination addresses in phishing emails sent by threat operators and of newly discovered C2s (i.e., the conversion of exfiltrated credentials to new C2s) reveals the tactics used to spread the attack from a compromised industrial enterprise to its business and operational partner organizations. These tactics are shown in the diagram below.

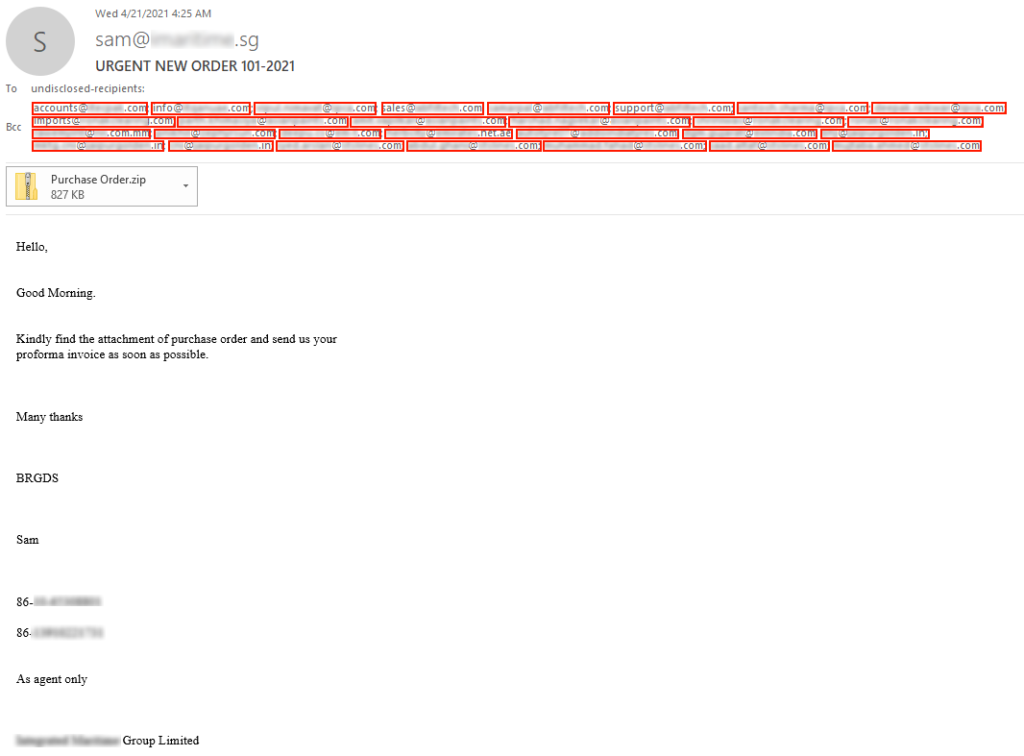

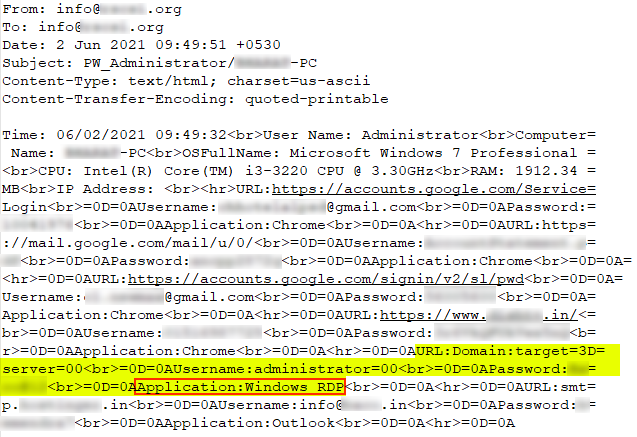

An example of a phishing email sent by a threat operator as a result of abusing stolen credentials (email account) of a victim user is shown below. The email was sent via the compromised organization’s email server from the compromised user’s account to targets taken from the compromised user’s contact list. The targets included 28 email accounts from 7 industrial companies.

Overall, as part of this research, we identified over 2,000 abused (i.e., used as C2s by spyware) email accounts owned by industrial companies. We estimate the total number of corporate email accounts whose credentials were stolen as a result of these attacks to be over 7,000.

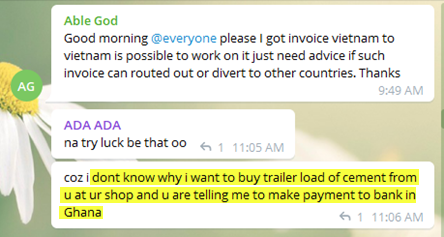

For some actors, the next-stage activity involved attacking their victims using the business email compromise technique, which is designed to enable the attackers to commit fraud (by analyzing business correspondence and hijacking selected banking transactions). An example of emails used in such attacks is shown below.

Other actors focus on stealing credentials for sale, including:

- Credentials for personal financial services such as online banking accounts, wallets, crypto exchanges, etc.;

- Credentials for social networks and other public internet services;

- Credentials for corporate network access services (SMTP, SSH, RDP, VPN, etc.).

Based on screenshots collected by spyware and other indirect evidence we have found, we can state that some malware operators have a particular interest in industrial companies and their infrastructure. This interest can be explained by significant differences in the prices of different account types in web marketplaces (see below).

At this stage in our research, the “anomaly” discovered early on makes perfect sense: the “anomalous” samples we discovered are so limited in scope and have such a short lifespan because threat actors generate unique samples (with a specific C2 configuration) for each phishing email, which is usually limited to a subset of addresses from the previous-stage victim’s contact list.

When a compromised email account is abused as a C2, the C2 traffic is normally detected by an antispam solution and moved to the spam folder, where in most cases it remains unnoticed until the folder is cleaned. Evading antispam detection is not in the interests of the malicious actors, as this would bring victims’ attention to C2 traffic, signaling compromise. That’s how malicious actors use cybersecurity-related technology to their advantage.

The Recommendations section of this report contains some patterns which could be used to identify the compromise of an email account.

Malware operators

An analysis of data on some malware operators covered by our research on “anomalous” spyware attacks has shed some light on the bigger picture of credential gathering campaigns run by hundreds of independent operators.

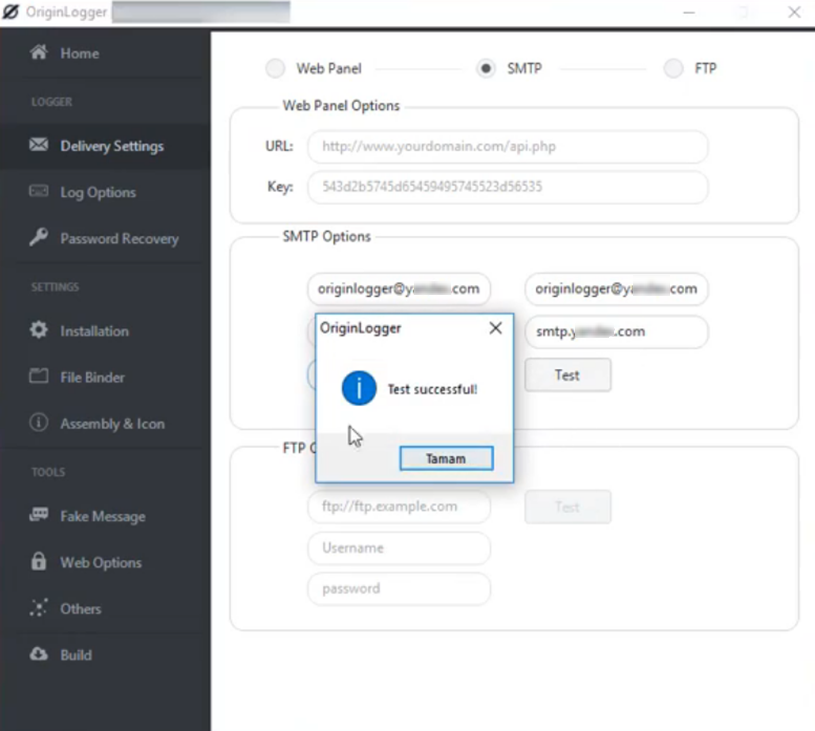

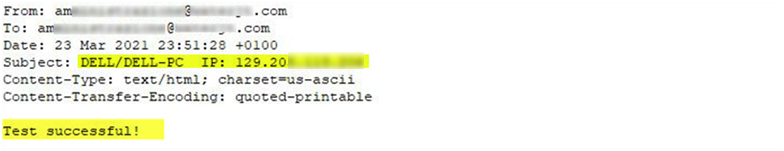

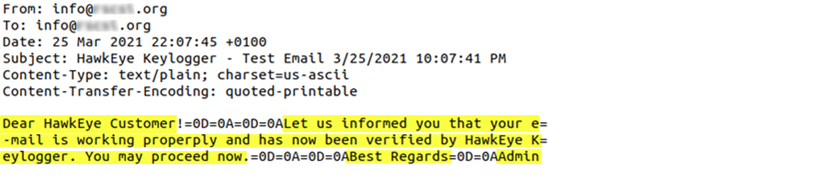

Various spyware builders have a feature for testing the availability and accessibility of a C2 at the configuration phase. In the case of an SMTP C2, they simply send and retrieve a test message.

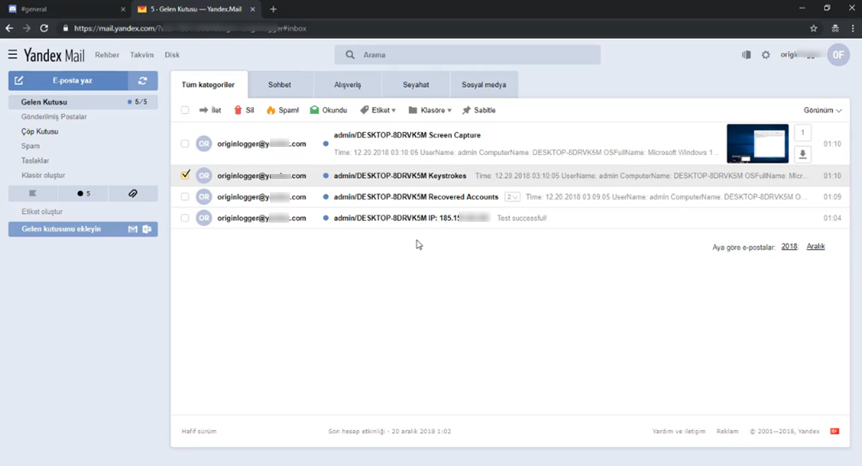

It can be seen in the screenshot of a C2 test message below that such messages can provide useful information about the infrastructure used by malware operators: the subject field of the test email contains the user name, the computer name, and the IP address of the machine from which the email was sent.

It has been shown by other researchers that builder features can include sending certain data to the malware developer, which means that malware developers can use them to spy on their customers. Other builders that send a greeting email to the spyware operator, such as HawkEye, don’t include much information about the malware operator.

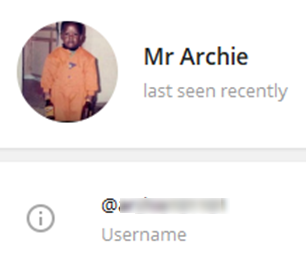

An analysis of some information on malware operators (most probably leaked when they were testing their malware on the PCs they use for their other day-to-day activities) allowed us to learn more about the TTPs of malware operators, the backend infrastructure they used to prepair their attacks, and the various services they used over the internet as part of their “work routine”, e.g., to rent the infrastructure, communicate with other cybergangsters or sell the loot.

The analysis has also revealed that many of these operators may be connected with African countries.

The IP addresses of host machines used by malware operators as their backend infrastructure are listed in “Appendix I – Indicators of compromise”.

Malware developers and Spyware-as-a-Service providers

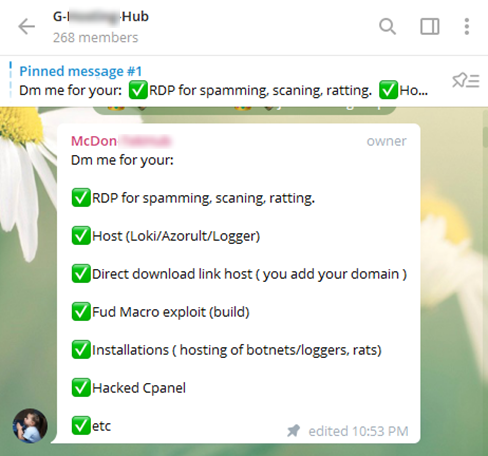

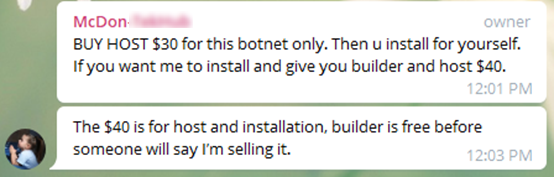

In the past 5 years, since the source code of some popular spyware programs was made public, it has become highly available in online shops in the form of a service – developers sell a license for a malware builder rather than for malware as a product.

In some cases, what malware developers sell is not a malware builder but access to infrastructure preconfigured to build the malware, at the same time advertising some additional services on top of it.

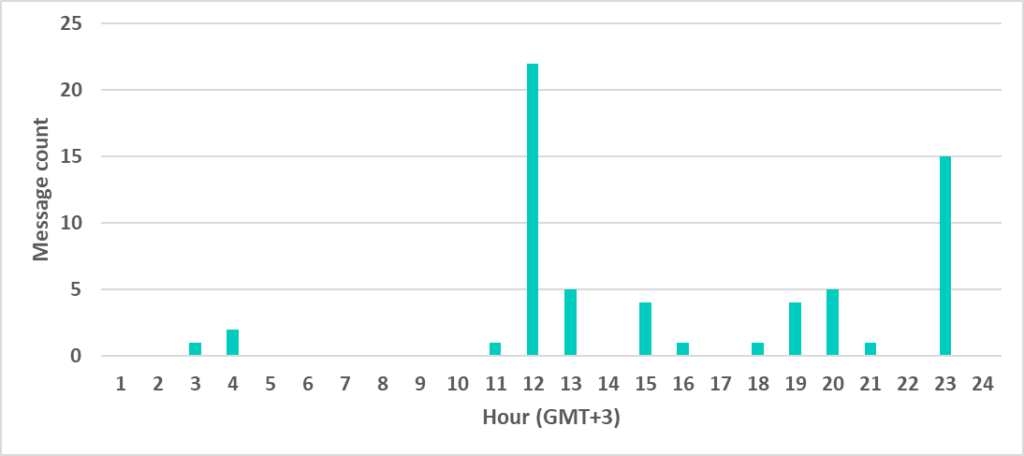

Many spyware developers advertise their products on social networks, forums, and chats; they even make video tutorials. We have analyzed all available sources of information published by many malware developers (those who are selling the spyware builders detected on ICS computers in 2021). As part of this research, we were able to track “anomalous” spyware attacks through their operators down to the specific MaaS infrastructure, its providers and developers. Further analysis of social networks, chats, and forums where these operators and developers communicate revealed that a significant proportion of these independent malware developers and service providers are likely to speak Russian (i.e., they may potentially be connected with post-Soviet states) and Turkish.

This observation is based on various facts:

- Probable time zone based on the time of day when the malware developers are active in chats/forums;

- Probable locale based on screenshots, videos, and messages shared by the malware developers.

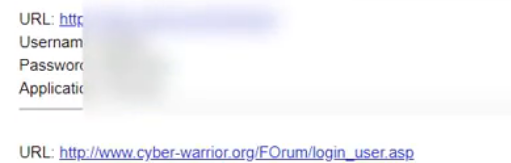

Another example is a video tutorial created by an OriginLogger seller. The interface of his Yandex mail account (seen on his video) is set to the Turkish locale. Moreover, the author did not use the blur effect in the video properly to hide the data collected by the spyware he was demonstrating. An analysis of URLs collected by the spyware from the demonstrators’ web browser shows he has accounts on some Turkish forums and even an account with a Turkish university.

Marketplaces

Along with some insights about the malware services used by threat operators (as well as malware developers and service providers), data on malware operators allows us to identify one of the routines used to monetize credential harvesting attacks (aside from business email compromise) – selling the stolen credentials in various marketplaces.

Our analysis of services and marketplaces used by the malware operators showed that credential harvesting campaigns are a building block of a huge pipeline of various malicious services, from the development of malware and its infrastructure to commerce platforms trading a wide variety of access to corporate networks of any choice.

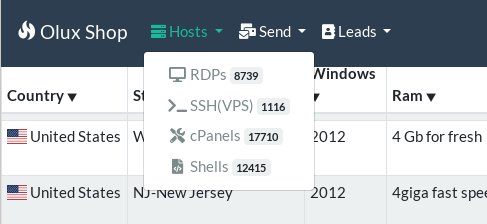

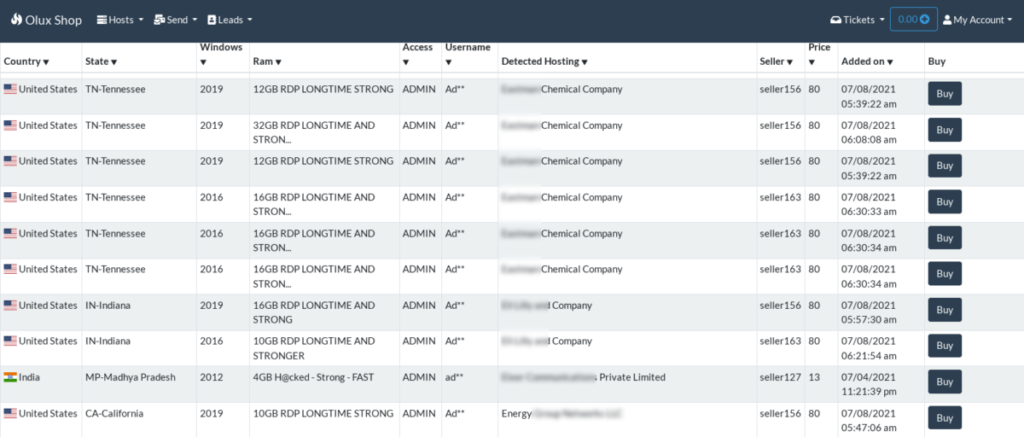

In this research, we identified over 25 different marketplaces where data stolen in the credential gathering campaigns targeting industrial companies that we investigated was being sold. At these markets, various sellers offer thousands of RDP, SMTP, SSH, cPanel, and email accounts, as well as malware, fraud schemes, and samples of emails and webpages for social engineering.

An analysis of offers and prices has revealed a trend: access to corporate networks of industrial enterprises (via RDP, SSH, SMTP, etc.) is priced 8-10 times higher than access to cloud hosting infrastructures such as AWS, DigitalOcean, Azure, etc.

A marketplace normally provides no information on sellers except their seller IDs. An analysis of the entire portfolio of accounts offered by a seller could show that seller’s focus on some particular types of accounts – some mainly offer accounts for corporate networks (e.g., networks of industrial companies).

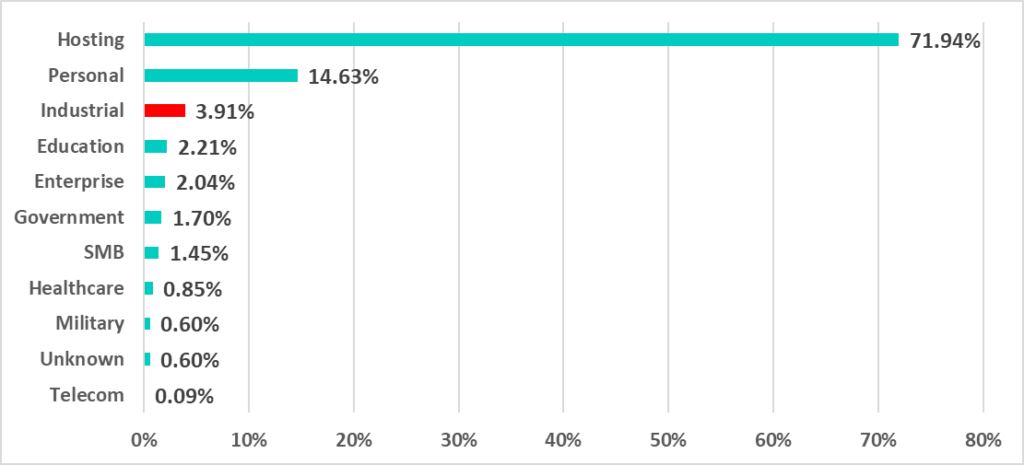

A statistical analysis of metadata for over 50,000 compromised RDP accounts sold in marketplaces shows that 1,954 accounts (3.9%) belong to industrial companies.

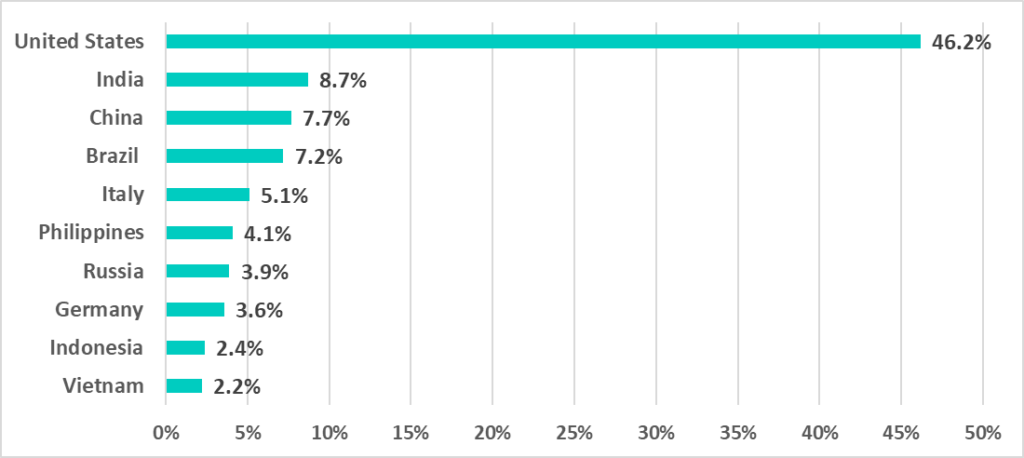

Statistics on compromised industrial enterprise accounts by country show that over 46% of accounts sold in marketplaces are owned by companies in the US, while owners of the rest are located in Asia, Europe, and Latin America.

Conclusion

The implementation of security measures and controls in IT and OT infrastructures worldwide forces the cybercriminal ecosystem to evolve. One of the changes in the approaches of malicious actors that we have seen is moving away from mass-scale attacks towards small-scale and very short-lived (in terms of both the C2 infrastructure and the malware samples) series of attacks. Another tactic was to propagate the attacks from inside the victim’s infrastructure, thereby “legitimizing” the phishing email traffic. Abusing legitimate mailboxes (compromised at a previous attack stage) enables the actors to rapidly change their C2s and limit detection by network security solutions. What makes this possible for threat actors is the ubiquitous use of antispam technologies in the modern mail systems of their victims.

This tactic has proved so effective that, depending on the region, it was used to attack up to one-sixth of all ICS computers we saw attacked with spyware during H1 2021.

According to our telemetry, more than 2,000 industrial organizations worldwide have been incorporated into the malicious infrastructure and used by cyber gangs to spread the attack to their contact organizations and business partners. According to our estimate, the C2 conversion rate is roughly 1/4, which gives us at least 7,000 corporate accounts compromised during the research period. The amount of data stolen from these accounts is hard to estimate.

There are many ways in which this data can be abused, including by the more devastating actors, such as ransomware gangs and APT groups. As an analysis of web marketplaces shows, the demand is highest for credentials that provide access to internal systems of enterprises. And the supply seems to be meeting the demand, as we counted almost 2,000 RDP accounts for industrial enterprises being sold in marketplaces during the analysis period.

Recommendations

We recommend taking the following measures to ensure adequate protection of an industrial enterprise, its partner network operations, and business:

- Consider implementing two-factor authentication for corporate email access and other internet-facing services (including RDP, VPN-SSL gateways, etc.) that could be used by an attacker to gain access to your company’s internal infrastructure and business-critical data.

- Make sure that all the endpoints, both on IT and OT networks, are protected with a modern endpoint security solution that is properly configured and is kept up-to-date.

- Regularly train your personnel to handle their incoming emails securely and to protect their systems from malware that email attachments may contain

- Regularly check spam folders instead of just emptying them

- Monitor the exposure of your organization’s accounts to the web

- Consider using sandbox solutions designed to automatically test attachments in inbound email traffic; make sure your sandbox solution is configured not to skip emails from “trusted” sources, including partner and contact organizations. No one is 100% protected from a compromise.

- Test attachments in outbound emails, as well. This could give you a chance to realize you’re compromised.

Appendix I – Indicators of compromise

Infrastructure IPs

105.112.101.7 105.112.102.213 105.112.107.100 105.112.109.252 105.112.113.164 105.112.113.250 105.112.114.120 105.112.115.230 105.112.115.4 105.112.117.199 105.112.121.59 105.112.144.173 105.112.144.56 105.112.144.77 105.112.145.6 105.112.147.156 105.112.147.20 105.112.148.252 105.112.148.60 105.112.150.35 105.112.178.164 105.112.26.202 105.112.32.44 105.112.33.155 105.112.33.233 105.112.33.40 105.112.35.117 105.112.37.192 105.112.37.193 105.112.37.222 105.112.38.173 105.112.38.201 105.112.38.218 105.112.38.249 105.112.39.130 105.112.39.167 105.112.41.0 105.112.41.149 105.112.46.233 105.112.46.38 105.112.50.73 105.112.50.80