Key Findings

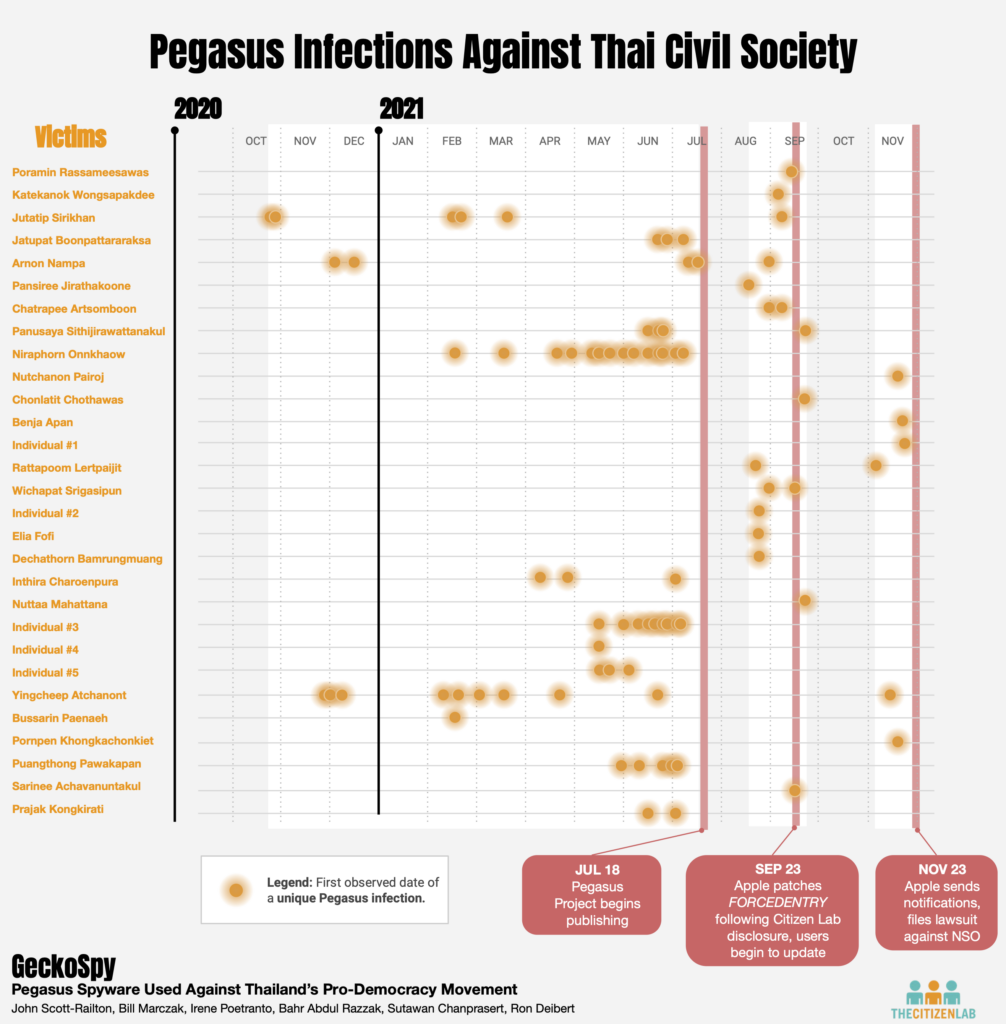

- We discovered an extensive espionage campaign targeting Thai pro-democracy protesters, and activists calling for reforms to the monarchy.

- We forensically confirmed that at least 30 individuals were infected with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware.

- The observed infections took place between October 2020 and November 2021.

- The ongoing investigation was triggered by notifications sent by Apple to Thai civil society members in November 2021. Following the notification, multiple recipients made contact with civil society groups, including the Citizen Lab.

- The report describes the results of an ensuing collaborative investigation by the Citizen Lab, and Thai NGOs iLaw, and DigitalReach.

- A sample of the victims was independently analyzed by Amnesty International’s Security Lab which confirms the methodology used to determine Pegasus infections.

This report is a companion to a report with detailed contextual analysis by iLaw and DigitalReach.

Introduction: Surveillance & Repression in Thailand

The Kingdom of Thailand is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary-style government divided into executive, legislative, and judiciary branches. The country has been beset by intense political conflict since 2005, during the government of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Corruption allegations against the regime culminated in a military coup on September 19, 2006 that ousted Thaksin. The military launched another coup on May 22, 2014 and seized power following mass protests against the civilian government led by Thaksin’s sister, Yingluck Shinawatra. The junta claimed that the 2014 coup was needed to restore order and called itself the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO).

Contemporary Political Contests

Thailand has had at least twelve successful coups, in addition to at least seven unsuccessful coup attempts, since the end of its absolute monarchy in 1932. Thailand’s 2019 elections, the first elections following the 2014 coup, did not restore parliamentary democracy, but instead returned the coup leaders to power and further institutionalized the military in government. One year later, Maha Vajiralongkorn, the son of the widely-popular King Bhumibol Adulyadej who died in 2016 after a seven decade reign, ascended the throne.

Dissatisfaction with the government and the monarchy led to mass protests and social media campaigns (e.g., “#WhyDoWeNeedAKing” and “#FreeYouth,” representing the Free Youth Movement of students) that have demanded a return to democracy and reforms of the monarchy. Inspired by the pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan, activists in Thailand joined the “Milk Tea Alliance” in 2020, named after a drink that is popular in the region. Activists including Arnon Nampa also organized a “Harry Potter vs. He Who Must Not Be Named”-themed protest, and protesters adopted the three-finger salute from the bestselling book and movie series The Hunger Games to demonstrate their defiance. Additionally, groups such as the Ratsadon, We Volunteer (WeVo), and Thalufah organized a rally in June 2022 to commemorate the anniversary of the 1932 revolution.

The government responded to the protests by launching a wave of arrests, citing Section 112 of Thailand’s Criminal Code (also known as the lèse-majesté law), which criminalizes insults and defamation against the Thai royal family and carries lengthy prison sentences, as well as other laws (e.g., Article 215 of the Criminal Code on illegal assemblies). United Nations (UN) human rights experts have expressed “grave concerns” over the use of lèse-majesté law against those who criticize the government and the monarchy, and protesters have mobilized against what they deem to be an arbitrary application of such laws.

Among those targeted with the lèse-majesté law was lawyer Arnon Nampa, who was arrested multiple times and faced multiple lèse-majesté charges, with a prison term of up to 150 years. Activists like Jatupat Boonpattararaksa (also known as “Pai Dao Din”), who already served prison sentences for lèse-majesté, were targeted repeatedly. Meanwhile, women activists and their family members have reported frequent physical harassment, intimidation, and surveillance, in addition to online harassment and attacks, resulting from their involvement in protests. Thai activists who have left the country also continue to face threats to their security. At least nine exiled activists have disappeared since 2014 in neighboring countries, such as Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Vietnam.

Information Controls in Thailand

Generally, Thai authorities have permitted greater freedom of expression on the Internet than other forms of state-controlled mass media. However, the 2006 and 2014 coups resulted in new laws and policies that transformed the Internet’s role as a platform for political exchanges and debates. For example, the Computer-Related Crime Act B.E 2550 (2007) (also known as the 2007 Computer Crime Act (CCA))—the very first legislation passed by the military-appointed legislature after the 2006 coup—is often applied in conjunction with the lèse-majesté law. In January 2021, a former civil servant pleaded guilty to 29 counts of lèse-majesté for uploading clips on social media that allegedly contained defamatory comments against the monarchy. The former civil servant received an 87 year prison sentence, which was later reduced to 43 years on appeal.

The political polarization that emerged from the protests and counter protests between the broadly populist-democratic “Red Shirts” supporters of Thaksin and the broadly conservative-royalist “Yellow Shirts,” consisting of middle class Thais, has also given rise to vigilantes that monitor the Internet and social media for potential lèse-majesté violations. The Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (MICT) runs the “Cyber Scouts” program, while groups such as the Garbage Collecting Organization have reported individuals to the police for alleged lèse-majesté crimes.

The 2006 and 2014 coups have been regarded as “twin coups,” as both were carried out by the same group of people in the military and both share a similar aim of eliminating Thaksin’s influence in Thai politics. The May 2014 coup, however, is distinct from previous coups, due to the military junta’s declaration of martial law before the coup and immediate efforts to restrict free speech online and offline. Furthermore, unlike the 2006 coup, the junta did not hold elections soon after seizing power, and instead established a military-dominated government.

The Citizen Lab previously tested website accessibility in Thailand between May 22, 2014 and June 26, 2014, which identified a total of 56 URLs blocked in the country, including “domestic independent news media websites and international media coverage that are critical of the coup, social media accounts sharing anti-coup material, as well as circumvention tools, gambling websites and pornography.” The military also engaged in information operations online, such as by creating several military-related official Facebook Pages following the coup.

The junta’s policies have contributed to more stringent controls on information and the silencing of dissent, including on the Internet. For example, in 2015 it announced the intention to merge all gateways to the global Internet from Thailand into a single entity to help control “inappropriate” websites and information flows from overseas. Although this single Internet gateway plan was dropped after widespread criticism and fears that it would be used to restrict access to online content, the Digital Economy and Society Minister Chaiwut Thanakhamanusorn suggested in February 2022 that a single Internet gateway remains necessary to protect national security and prevent cyber crimes.

The junta-appointed National Legislative Assembly amended the CCA in 2017, adding provisions that allow the government to prosecute what it designates as “false” or “distorted” information. Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, a former military chief who led the 2014 coup, defended the amendment as necessary to control “inappropriate” online content, especially those that defame the monarchy. Section 26 of the amended CCA requires Internet service providers (ISPs) to “retain the necessary information of the service user in order to be able to identify the service user from the beginning of the service provision.” This section is concerning given the country’s history of prosecuting Internet users and publishers for their free expression. For example, Thantawut Thaweewarodomkul, a web designer for a “Red Shirt”-affiliated website called Nor Por Chor USA, was sentenced in 2011 to 13 years in prison due to comments posted on the website that violated the lèse-majesté law and failure to remove these comments. The Thai news site Prachatai reported that a Thai ISP, Triple T Broadband Company, had revealed an IP address to the authorities allegedly belonging to Thantawut that was connected to the website.

The junta established a new Constitution in 2017 that, among other things, introduced new structures for the military to intervene in politics (e.g., a new Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) with local commands in every province). The military-appointed parliament further extended the government’s powers in February 2019 by passing both the Cybersecurity Act and the National Intelligence Act. Both Acts have been criticized for giving the authorities virtually unaccountable power to monitor Internet users and collect user data, given their overly broad and vague language, including regarding what is considered as “national security,” and allowing the use of “any methods” by the government to obtain information (Section 6 of the 2019 National Intelligence Act). Although Thailand passed the Personal Data Protection Act in May 2019, concerns over unchecked surveillance and the misuse of government-collected personal data remain, as the Act contains many exemptions to enforcement, including exempting government agencies responsible for “state security” (Section 4).

Thai authorities have routinely pressured social media companies to remove posts considered offensive or a threat to the junta. A 2020 Amnesty International report claimed that “Thai authorities are prosecuting social media users who criticize the government and monarchy in a systematic campaign to crush dissent.” This approach is exemplified in the blocking of a Facebook group with more than a million followers, called the Royalist Marketplace, founded by Thai academic and critic in exile, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, following a request from Thai officials. Although Facebook complied with the request, it noted that ‘[r]equests like this are severe, contravene international human rights law, and have a chilling effect on people’s ability to express themselves,” and that the company would undertake a legal challenge in Thai courts.

Targeted and Mass Surveillance in Thailand

As pro-democracy protests have become more widespread, activists and protesters are increasingly concerned over surveillance conducted by the Thai authorities. Outside of the capital city of Bangkok, where most of the protests take place, mobile service providers have required their users to submit biometric data (e.g., in the restive Southern Border Provinces, which are populated by minority ethnic Malay Muslims). A system of over 8,000 artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled surveillance cameras has also been planned for the region and Thai authorities have reportedly started collecting involuntary DNA samples from the local population.

National legislation in Thailand has thus far failed to introduce checks and balances against the government’s broad and continuously evolving surveillance powers, while mechanisms to hold the government accountable are being weakened and attacks against civil society continue. In 2013 and 2015, the government allegedly purchased surveillance technologies made by the Italian company Hacking Team. Previous research published by the Citizen Lab in 2020 indicates that at least three Thai government agencies had contracted with Circles, which offers a complementary product to Pegasus that allows for the interception of phone calls and SMS, as well as tracking of a phone’s location, without hacking the device. The three Thai customers of Circles that the Citizen Lab identified were the Narcotics Suppression Bureau (NSB), the Thai Army’s ISOC (กองอำนวยการรักษาความมั่นคงภายใน), and the “Military Intelligence Battalion” (MIBn) (กองพันข่าวกรองทางทหาร).

Concerns over the use of Pegasus spyware against pro-democracy protesters in Thailand stem from the Citizen Lab’s previous reporting of a potential Pegasus spyware operator within the country in 2018. Furthermore, in November 2021, Reuters reported that six activists and researchers received “state-sponsored attacker” notifications from Apple. These notifications triggered this report’s investigation on the use of Pegasus in Thailand.

Findings: Pegasus Infections in Thailand

On November 23, 2021, Apple began sending notifications to iPhone users targeted by state-backed attacks with mercenary spyware. The recipients included individuals that Apple believes were targeted with NSO Group’s FORCEDENTRY exploit. Many Thai civil society members received this warning. Shortly thereafter, multiple recipients of the notification made contact with the Citizen Lab and regional groups.

In collaboration with Thai organizations iLaw1 and DigitalReach, forensic evidence was obtained from notification recipients, and other suspected victims, who consented to participate in a research study with the Citizen Lab. We then performed a technical analysis of forensic artifacts to determine whether these individuals were infected with Pegasus or other spyware. Victims publicly named in this report consented to be identified as such, while others chose to remain anonymous, or have their cases described with limited detail.

Civil Society Pegasus Infections

We have identified at least 30 Pegasus victims among key civil society groups in Thailand, including activists, academics, lawyers, and NGO workers. The infections occurred from October 2020 to November 2021, coinciding with a period of widespread pro-democracy protests, and predominantly targeted key figures in the pro-democracy movement. In numerous cases, multiple members of movements or organizations were infected.

Many of the victims included in this report have been repeatedly detained, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities or criticism of the government. Many of the victims have also been the subject of lèse-majesté prosecutions by the Thai government.

While many of the infections were detected on the devices of prominent figures, hacking was also observed against individuals who are not publicly involved in the protests. Speculatively, this may reflect the attackers’ intent to uncover details about how opposition movements were organized, and may have been prompted by specific financial transactions that would have been known to Thai financial institutions and the government, but not the public.

The following section outlines a selection of these cases.

A more detailed discussion of these cases and more by iLaw and Digital Reach Asia can be found by CLICKING HERE TO READ THEIR REPORT

Members of Movements or Organizations

Members of the anti-government protest movement, including individuals associated with FreeYOUTH, United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration (UFTD), and We Volunteer (WEVO), were infected with Pegasus, often during periods of political activity. For example, some of the hacking took place shortly before, during, or after protests, suggesting that the attackers may have been seeking information about their activities.

Target: FreeYOUTH

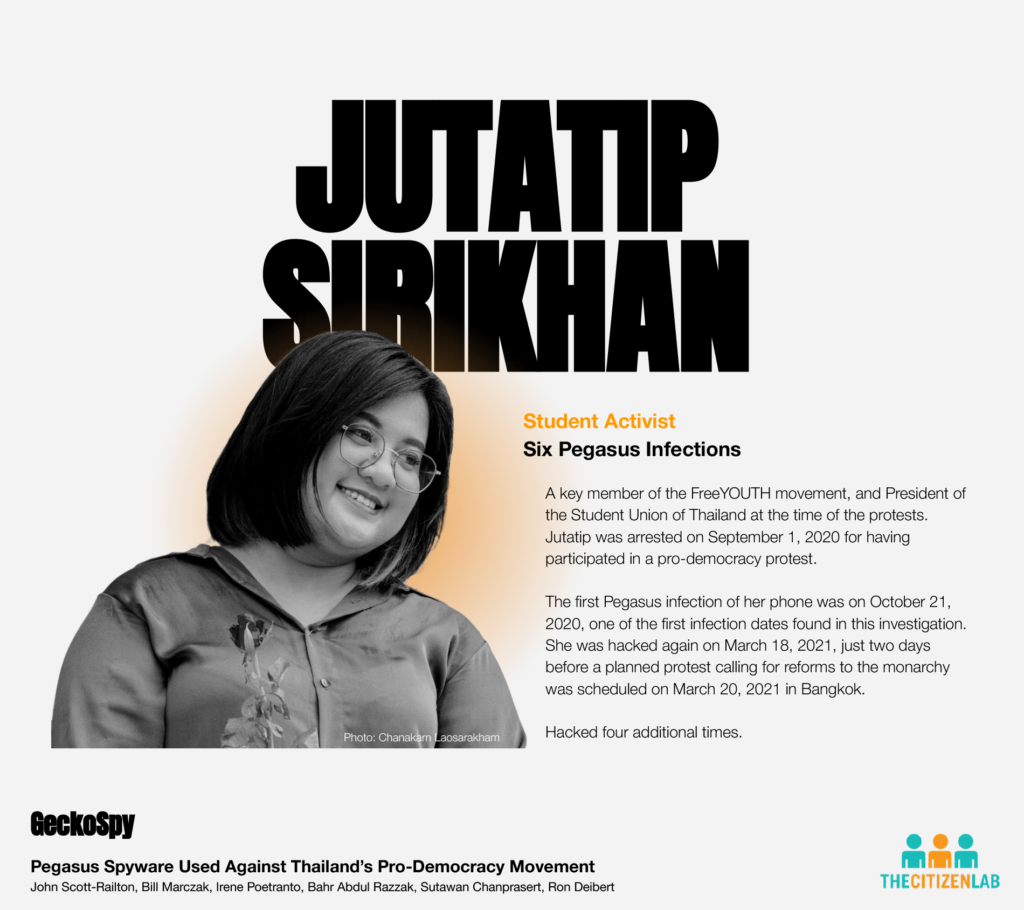

Jutatip Sirikhan is a key member of the FreeYOUTH movement who was the President of the Student Union of Thailand at the time of the protests. Jutatip was arrested on September 1, 2020 for having participated in a pro-democracy protest. The Citizen Lab observed evidence of an infection of her phone on or around October 21, 2020, one of the first infection dates found in this investigation. She was again hacked on March 18, 2021, just two days before a planned protest calling for reforms to the monarchy was scheduled on March 20, 2021 in Bangkok. We determined her device was infected a total of six times.

Other FreeYOUTH members and close affiliates who were also infected with Pegasus include Poramin Rassameesawas,2 Katekanok Wongsapakdee, Pansiree Jirathakoone, and Chatrapee Artsomboon. Another member of the group, Ratchasak Komgris, received a notification from Apple, but no conclusive evidence of infection was found at the time of forensic analysis.

Target: WEVO

Members of We Volunteer (WEVO) were also infected with Pegasus. The group is often referred to as “Guard WEVO,” as they provide support to other protest groups. Piyarat Chongthep, the group’s former president, was infected with Pegasus, according to forensic indicators present on the device, although the exact date of the infection could not be determined at the time of analysis. At least three additional WEVO members were also infected with Pegasus: Rattapoom Lertpaijit, Wichapat Srigasipun, and Individual #2 were infected between August and September 2021. 3According to the group’s official Facebook page, at the time of infection, at least 66 WEVO members were charged with multiple offenses, including violations of the Emergency Decree, and illegal association. Piyarat was also charged for committing a lèse-majesté offense.

Target: UFTD

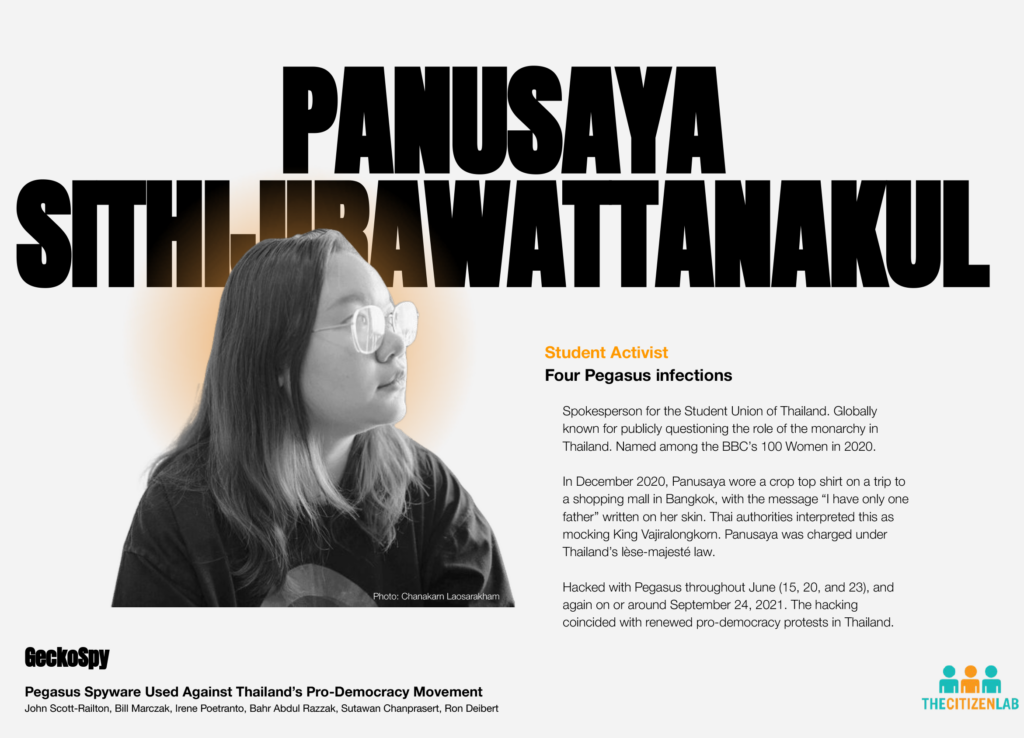

At least four members of the United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration (UFTD), a prominent youth movement from Thammasat University in Bangkok, were infected with Pegasus: Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul, Niraphorn Onnkhaow, Nutchanon Pairoj, and Chonlatit Chottsawas. Benja Apan, a former UFTD member, was also infected. Panusaya, who is also a spokesperson for the Student Union of Thailand, is globally known for publicly reading a document challenging the role of the monarchy in Thailand. Her activism led to her being named among the BBC’s 100 Women in 2020.

In December 2020, Panusaya wore a crop top shirt on a trip to a shopping mall in Bangkok, with the message “I have only one father” written on her skin. Thai authorities interpreted this as mocking King Vajiralongkorn. Panusaya was charged under Thailand’s lèse-majesté law. In November 2021, a Thai court also ruled that demands voiced by protest leaders Panusaya, Arnon Nampa, and Panupong “Mike” Jadnok to reform the monarchy during mass protests in 2020 were unconstitutional. In total, Panusaya has been charged with at least 10 lèse-majesté offenses, and was detained for a total of 85 days between 2020 and 2021. The charges drew widespread condemnation by human rights groups and legal scholars.

Our analysis revealed that Panusaya was repeatedly hacked with Pegasus throughout June (15, 20, and 23), and again on or around September 24, 2021. The hacking coincided with renewed pro-democracy protests in Thailand. During the periods when Panusaya was jailed, Nutchanon and Benja assisted in the UFTD’s leadership. Benja, for example, publicly read the group’s second declaration. Nutchanon and Benja were sentenced to prison on a “contempt of court charge” due to a protest at the Ratchadaphisek Criminal Court on April 29, 2021, which demanded the release of detained activists. Nutchanon and Benja had also organized another protest in front of the Ratchadaphisek Criminal Court on April 30, 2021.

In November 2021, Nutchanon and Benja were sentenced to contempt of court. Both were infected with Pegasus in November 2021. Benja’s phone was infected on November 17, 2021. Nutchanon’s phone, meanwhile, was infected on November 18, 2021. Benja’s device was infected with Pegasus while she was in detention after being arrested on October 7, 2021. She spent 99 days in prison after being repeatedly denied bail for lèse-majesté and other offenses. The phone was not in her custody during this period.

Niraphorn, meanwhile, was infected with Pegasus at least 12 times between February and June 2021. This hacking is especially interesting given that she played a support role in protest organizing, rather than serving as a protest leader. For example, Niraphorn is known as a co-registrant of the UFTD’s bank account that is used to accept donations. Some of the infections took place shortly before protests, such as an infection on March 19, 2021, just days before a Bangkok protest that demanded political reforms and the release of protest leaders. It is possible that the attackers were seeking information about the groups’ organization and fundraising efforts. Niraphorn was arrested and charged in September 2021 for administering the UFTD’s Facebook page.

Prominent Individuals

Target: Jatupat Boonpattararaksa

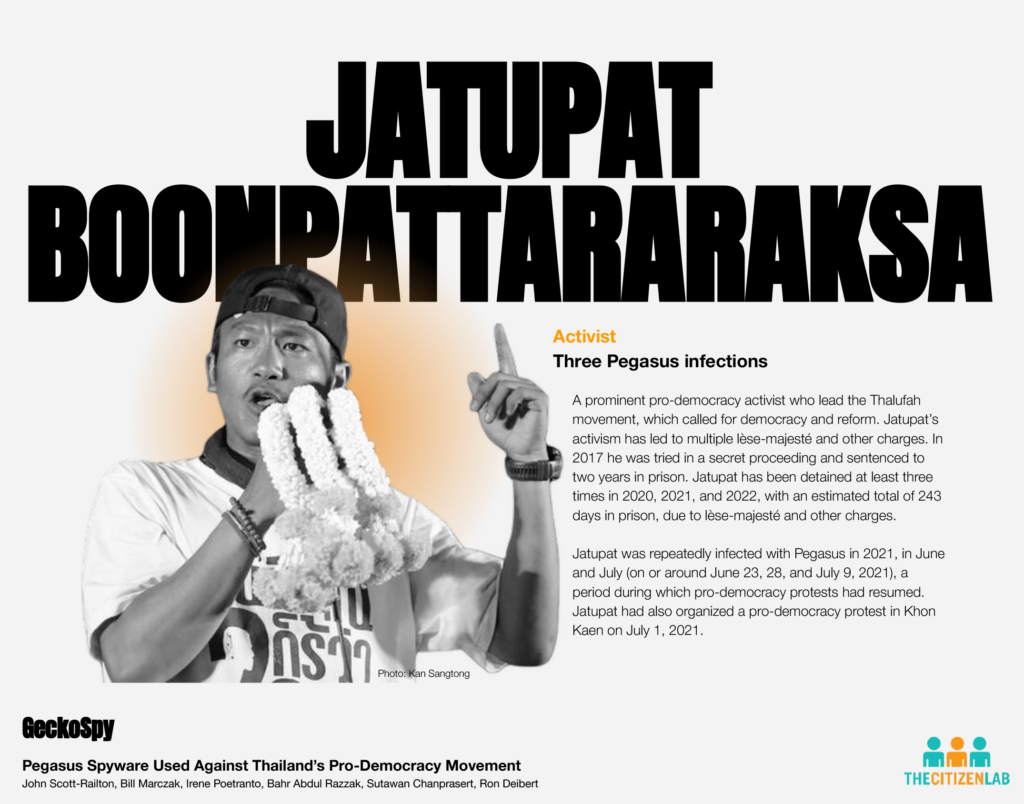

Jatupat Boonpattararaksa (also known as “Pai Dao Din”) is a prominent pro-democracy activist who has been active since 2014. Jatupat led the “Thalufah” (“Through the Sky”) pro-democracy group, which takes its name from a 200 km-long protest march from Nakhon Ratchasima to Bangkok’s Democracy Monument from February 16 to March 7, 2021. The march called for a democratic constitution, the release of political activists, and repeal of the lèse-majesté law. Subsequent rallies by Thalufah were met with a violent police response, including rubber bullets and tear gas. Jatupat’s activism has led to multiple lèse-majesté and other charges. In 2017, for example, he was tried in a secret proceeding and sentenced to two years in prison. Jatupat was detained at least three times in 2020, 2021, and 2022, and spent an estimated total of 243 days in prison, due to lèse-majesté and other charges.

Jatupat was repeatedly infected with Pegasus in 2021, in June and July (on or around June 23, 28, and July 9, 2021), a period during which pro-democracy protests had resumed. Jatupat had also organized a pro-democracy protest in Khon Kaen on July 1, 2021.

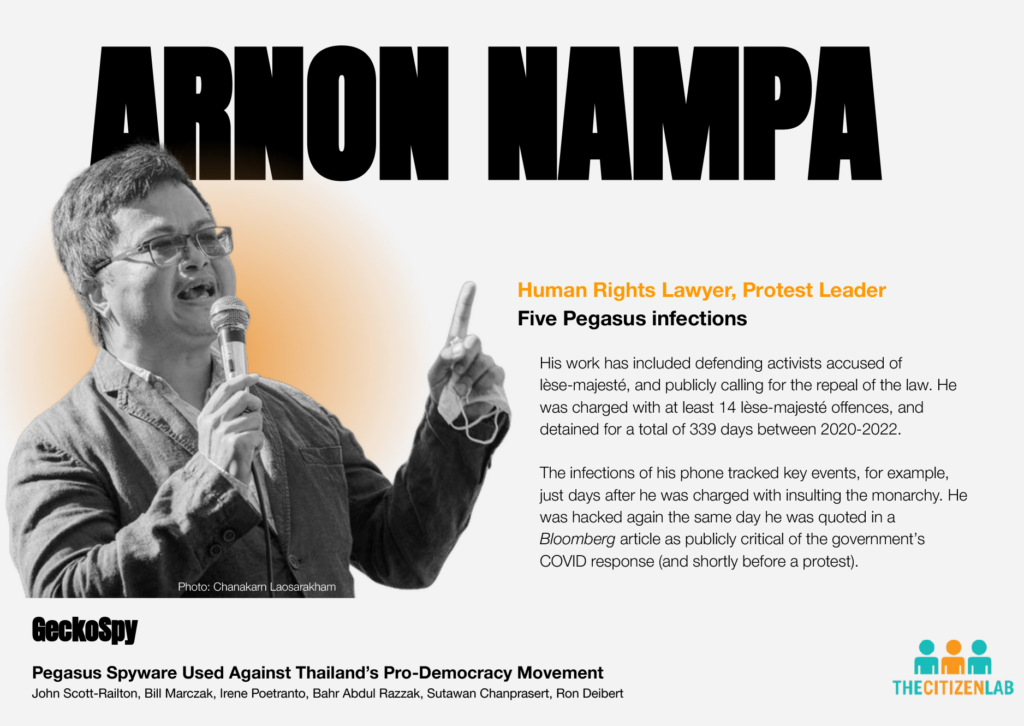

Target: Arnon Nampa

Arnon Nampa is a leading human rights lawyer and protest leader. His work has included defending activists accused of lèse-majesté, and publicly calling for the repeal of the law. He was charged with at least 14 lèse-majesté charges and was detained for a total of 339 days between 2020-2022.

Arnon was infected with Pegasus multiple times throughout 2020 and 2021. The first detected infection occurred on or around December 3, 2020, just days after he was charged alongside other activists with insulting the monarchy. A second infection took place less than two weeks later on December 15, 2020. He was subsequently arrested. After spending 113 days in jail, Nampa was infected with COVID-19. He was released on bail on June 1, 2021.

Arnon was again infected with Pegasus on or around July 14, 2021, shortly before a large-scale protest, and on the same day that he was quoted in a Bloomberg article which outlined how protest leaders were pushing for expansion of the Thai government’s struggling COVID-19 vaccination program. After participating in a Harry Potter-themed protest on August 3, 2021, Arnon was summoned and detained on August 9, 2021 and he was once more charged with lèse-majesté offenses. He was subject to a widely-criticized detention that lasted until he was released on bail on February 28, 2022. While he was in custody, his phone, which he did not have in his possession at time of his arrest, but remained active, was hacked with Pegasus on or around August 31, 2021.

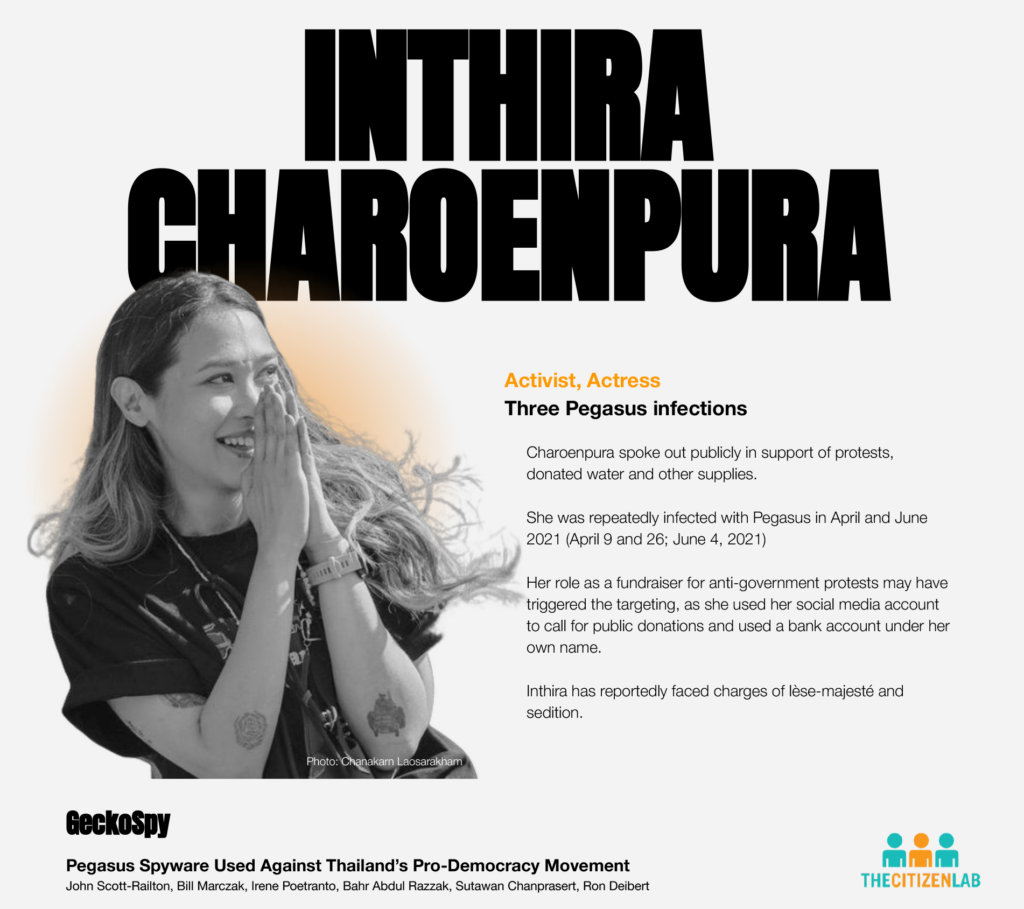

Target: Inthira Charoenpura

Anti-government protest organizers, high profile protesters, and spokespeople were not the only ones infected. Thai actress, Inthira Charoenpura, who spoke out publicly in support of protests and donated water and other supplies, was repeatedly infected with Pegasus throughout April and June 2021 (April 9 and 26; June 4, 2021). Speculatively, her role as a fundraiser for anti-government protests may have triggered the targeting, as she used her social media account to call for public donations and used a bank account under her own name. Inthira has reportedly faced charges of lèse-majesté and sedition.

Target: “The Mad Hatter”

Three members from an anonymous group of individuals that contributed funds to help support the protests, which we refer to as “the Mad Hatter” as a pseudonym in this report, were also infected with Pegasus. These individuals stated that they have often joined the protests as participants, but have never served as organizers or speakers.

Target: Dechathorn Bamrungmuang

Dechathorn Bamrungmuang, a popular rapper known by the stage name “Hockhacker,” was arrested and charged with sedition and other offenses after performing at a pro-democracy protest.

As a founder of the “Rap Against Dictatorship” (RAD) group, Dechathorn writes lyrics that are critical of the government and detail political problems in the country. RAD’s single, “My Country Has” became viral in 2018, receiving more than 100 million views on YouTube. In January 2021, YouTube blocked the music video of their song, entitled “Reform,” in Thailand following the government’s request. Dechatorn’s device was hacked with Pegasus on or around August 18, 2021, almost one year after his 2020 arrest.

Full List: Civil Society Victims

| No. | Name | Affiliations | Approximate Dates of Infection (year-month-date) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poramin Rassameesawas | FreeYOUTH | – On or around 2021-09-12 |

| 2 | Katekanok Wongsapakdee | FreeYOUTH | – On or around 2021-09-05 |

| 3 | Jutatip Sirikhan | FreeYOUTH | – On or around 2020-10-21

– On or around 2020-10-26 – On or around 2021-02-15 – On or around 2021-02-20 – On or around 2021-03-18 – On or around 2021-09-06 |

| 4 | Jatupat Boonpattararaksa | Thalufah | – On or around 2021-06-23

– On or around 2021-06-28 – On or around 2021-07-09 |

| 5 | Arnon Nampa | Independent Activist/Human Rights Lawyer at TLHR | – On or around 2020-12-03

– On or around 2020-12-15 – On or around 2021-07-10 – On or around 2021-07-14 – On or around 2021-08-31 |

| 6 | Pansiree Jirathakoone | Salaya for Democracy | – On or around 2021-08-17 |

| 7 | Chatrapee Artsomboon | Salaya for Democracy | – On or around 2021-08-30

– On or around 2021-09-09 |

| 8 | Panusaya Sithijirawattanakul | United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration | – On or around 2021-06-15

– On or around 2021-06-20 – On or around 2021-06-23 – On or around 2021-09-24 |

| 9 | Niraphorn Onnkhaow | United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration | – On or around 2021-02-16

– On or around 2021-03-16 – On or around 2021-04-26 – On or around 2021-04-30 – On or around 2021-05-11 – On or around 2021-05-14 – On or around 2021-05-20 – On or around 2021-05-31 – On or around 2021-06-08 – On or around 2021-06-15 – On or around 2021-06-20 – On or around 2021-06-23 – On or around 2021-07-01 – On or around 2021-07-07 |

| 10 | Nutchanon Pairoj | United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration | – On or around 2021-11-18 |

| 11 | Chonlatit Chottsawas | United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration | – On or around 2021-09-23 |

| 12 | Benja Apan | Independent Activist/United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration (Former) | – On or around 2021-11-17 |

| 13 | Individual #1 | Independent Activist | – On or around 2021-11-19 |

| 14 | Rattapoom Lertpaijit | WEVO | – On or around 2021-08-21

– On or around 2021-11-04 |

| 15 | Wichapat Srigasipun | WEVO | – On or around 2021-08-30

– On or around 2021-09-13 |

| 16 | Piyarat Chongthep | WEVO | Infection confirmed, but no dates known. |

| 17 | Individual #2 | WEVO | – On or around 2021-08-18 |

| 18 | Elia Fofi | Free Arts | – On or around 2021-08-17 |

| 19 | Dechathorn “Hockey” Bamrungmuang | Rap Against Dictatorship | – On or around 2021-08-18 |

| 20 | Inthira Charoenpura | Independent Activist | – On or around 2021-04-09

– On or around 2021-04-26 – On or around 2021-06-04 |

| 21 | Nuttaa Mahattana | Independent Activist | – On or around 2021-09-23 |

| 22 | Individual #3 | The Mad Hatter* | – On or around 2021-05-15

– On or around 2021-05-31 – On or around 2021-06-07 – On or around 2021-06-16 – On or around 2021-06-19 – On or around 2021-06-23 – On or around 2021-06-27 – On or around 2021-07-02 – On or around 2021-07-05 |

| 23 | Individual #4 | The Mad Hatter* | – On or around 2021-05-14 |

| 24 | Individual #5 | The Mad Hatter* | – On or around 2021-05-14

– On or around 2021-05-19 – On or around 2021-06-05 |

| 25 | Yingcheep Atchanont | iLaw | – On or around 2020-11-28

– On or around 2020-12-01 – On or around 2020-12-08 – On or around 2021-02-10 – On or around 2021-02-16 – On or around 2021-03-04 – On or around 2021-03-16 – On or around 2021-04-23 – On or around 2021-06-20 – On or around 2021-11-12 |

| 26 | Bussarin Paenaeh | iLaw | – On or around 2021-02-17 |

| 27 | Pornpen Khongkachonkiet | Cross Cultural Foundation | – On or around 2021-11-16 |

| 28 | Puangthong Pawakapan | Academic | – On or around 2021-05-31

– On or around 2021-06-10 – On or around 2021-06-25 – On or around 2021-06-30 – On or around 2021-07-02 |

| 29 | Sarinee Achavanuntakul | Academic | – On or around 2021-09-15 |

| 30 | Prajak Kongkirati | Academic | – On or around 2021-06-14

– On or around 2021-07-02 |

Table 1: Full list of civil society targets in Thailand

*A pseudonym

Research Methodology

The investigation collected4 forensic evidence from iPhones using a snowball-sampling method in which we ask known victims to assist us and our partners to identify other potential victims. First, we checked forensic artifacts shared by individuals who received a notification from Apple. Then, with the support of Thai NGOs iLaw and DigitalReach, we worked with victims to solicit forensic artifacts from their contacts, and then checked those.

Forensic Analysis

In general, we perform forensics by identifying evidence of Pegasus-linked binaries, processes, and artifacts in phone logs. We use indicators gleaned from our six years of tracking Pegasus spyware infections, including samples of Pegasus code we obtained from infected devices. In some cases, the forensic evidence we identify has an associated timestamp, allowing us to determine dates associated with the infection of a device. In other cases, we can bound the introduction of certain artifacts onto the device by a range of dates.

A positive finding for Pegasus indicates that we have assessed with high confidence that a phone has been successfully hacked with Pegasus spyware and that we do not believe there is any plausible alternative explanation for the indicators.

Independent Forensic Validation

In the context of ongoing targeted threats investigations, we typically reserve some indicators from publication in order to maintain visibility into the threat actor’s activities going forward. To provide independent validation of our assessments of Pegasus infection, we shared a sample of forensic artifacts from five Pegasus victims with Amnesty International’s Security Lab. Amnesty International’s Security Lab has independently developed their own methodology for detecting Pegasus that includes their Mobile Verification Toolkit (MVT) tool.

We shared the sample with Amnesty International’s Security Lab with victims’ consent, but without providing details of our findings. Amnesty examined the cases of:

- Puangthong Pawakapan

- Elia Fofi

- Yingcheep Atchanont

- Jatupat Boonpattararaksa

- Panusaya Sithijirawattanakul

Amnesty Security Lab’s assessment confirming Pegasus infections for these cases matches our own findings.

Zero-click exploits

Forensic evidence from the examined devices indicates that two zero-click exploits were used against the phones we examined: the KISMET and FORCEDENTRY exploits. We saw no evidence of one-click exploits used.

KISMET Exploit

The earliest cases of infections we identify in this report were carried out with the KISMET exploit, starting in October 2020. KISMET was a zero-click iOS exploit that appears to have been deployed by NSO Group customers between July and December 2020. While all compromises of Thai victims with KISMET that were identified occurred on out-of-date phones, other NSO Group customers deployed KISMET as a zero-day against iOS 13.5.1 and iOS 13.7.

While the precise nature of the KISMET exploit is unknown, it appears that malicious image files were sent to phones and hijacked control of IMTranscoderAgent to launch a WebKit instance for further exploitation. The KISMET exploit did not appear to work against iOS14, perhaps because of a mitigation introduced in that version, such as Apple’s BlastDoor feature.

FORCEDENTRY Exploit

The FORCEDENTRY exploit was deployed against Thai iPhones starting in February 2021. FORCEDENTRY was a zero-click iOS exploit delivered via iMessage. The FORCEDENTRY exploit5 involved the delivery of malicious PDF files with JBIG2 streams named using the “.gif” extension. The “.gif” extension caused IMTranscoderAgent to automatically parse the PDF files without user intervention. The PDF files hijacked control of the JBIG2 parser, escaped the IMTranscoderAgent sandbox, and downloaded a subsequent payload to enable further exploitation. The FORCEDENTRY exploit appears to have been deployed against Thai phones between February and November 2021, including as a zero-day against several versions of iOS 14, including iOS 14.4, 14.6, and 14.7.1. Apple fixed FORCEDENTRY in iOS 14.8.

Pegasus in Thailand

The first evidence of a Pegasus operator in Thailand we observed dates to May 2014. We observed a cluster of Pegasus servers in Rapid7’s sonar-http data, active starting in May 2014, which we assessed were operated from the GMT+7 timezone based on their HTTP headers. The GMT+7 time zone is used by Thailand, among other countries. The servers were also pointed to by Thai-themed domain names. We were not able to identify the specific agency behind this operator.

| IP | Domain | First Match |

|---|---|---|

| 69.28.93[.]191 | siamha[.]info | 27-05-2014 |

| 54.187.156[.]128 | thtube[.]video | 27-05-2014 |

| 54.187.191[.]4 | thainews[.]asia | 25-11-2014 |

| 69.28.93[.]2 | – | 25-11-2014 |

Table 2: Pegasus servers we assessed were operated from the GMT+7 time zone.

While conducting Internet scanning for our 2016 Million Dollar Dissident report, we identified a cluster of Pegasus servers pointed to by domains registered to an individual in Thailand with two email addresses, including [redacted].nsb18@gmail.com. The other email address was used to register a Facebook page under the name of “Nsbtest Nsbtest.” In the context of Thailand, “NSB” might refer to the Narcotics Suppression Bureau. We are unsure whether this operator overlaps with the 2014 activity we discovered, or whether it is separate. We are redacting these domain names as we continue to investigate this case.

In our 2018 Hide and Seek report, we identified a single Pegasus operator active in Thailand that we named CHANG. We are unsure whether this operator overlaps with the 2014 or 2016 clusters. We clustered domain names we found in our Hide and Seek report using the Athena method, and then conducted DNS cache probing to identify in which countries the operator was active. CHANG was active exclusively in Thailand.

| IP | Domain |

|---|---|

| 211.104.160[.]205 | 1place-togo[.]com |

| 103.212.223[.]182 | accounts-unread[.]com |

| 200.7.111[.]156 | breakingnewsasia[.]com |

| 200.7.111[.]155 | funnytvclips[.]com |

| 103.199.16[.]12 | normal-brain[.]com |

| 200.7.111[.]154 | paywithcrytpo[.]com |

| 45.32.105[.]249 | sexxclip[.]com |

| 159.89.193[.]231 | so-this-is[.]com |

| 185.128.24[.]118 | stayallalone[.]com |

Table 3: CHANG Pegasus servers. DNS Cache probing showed victims exclusively in Thailand.

As of the date of publication of this report, we assess that there is currently at least one Pegasus operator active in Thailand, though we cannot establish which specific agency this represents, or whether this operator overlaps with the 2018, 2016, or 2014 activity.

Attribution

We do not conclusively attribute the Pegasus hacking operation to a specific governmental operator. NSO Group consistently claims that their technology is sold exclusively to governments, which appears to be broadly true based on past research and revelations by journalists, the Citizen Lab, and other groups. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the discovery of Pegasus spyware indicates the presence of a government operator.

The forensic evidence collected from infected devices, taken by itself, does not provide strong evidence pointing to a specific NSO Group customer. However, numerous elements of the case, when taken together, provide circumstantial evidence suggesting one or more Thai government Pegasus operators is responsible for the operation:

- The victims were of intense interest to the Thai government.

- The hacking points to a sophisticated understanding of non-public elements of the Thai activist community, including funding and roles of specific individuals.

- The timing of the infections is highly relevant to specific political events in Thailand, as well as specific actions by the Thai justice system. In many cases, for example, infections occurred slightly before protests and other political activities by the victims.

- There is longstanding evidence showing Pegasus presence in Thailand, indicating that the government would likely have had access to Pegasus during the period in question.

We have examined other possible explanations for these findings, such as a different governmental Pegasus customer from a country outside Thailand. While this scenario is possible, a number of elements makes it unlikely. Conducting such an extensive hacking campaign against high profile individuals in another country is risky and runs the possibility of discovery, especially given the well-known previous cases where Pegasus infections were publicly discovered and publicly disclosed.

In addition, the victimology, and in some cases the timing of the infections, reflects information that would be easily available to the Thai authorities, such as non-public relationships and financial activity, but substantially more challenging for other governments to obtain.

Southeast Asian governments and some high profile individuals are known to be targeted by well-resourced state-sponsored hacking groups from abroad. It is quite possible that other states would have taken an interest in the outcome of protest activities in Thailand; however, Pegasus spyware is distinct from the techniques and tools used by regionally-focused and well-documented Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups.

Conclusion: Spyware and Political Repression in Thailand

The human rights situation in Thailand has continued to deteriorate since the 2014 coup. Rights activists have criticized the Thai government for conducting judicial harassment and arbitrary detentions, particularly against those who call for reforms of the monarchy and the restoration of democracy. Advocacy groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have also condemned the government for their excessive use of force, including “beating demonstrators and firing chemicals from water cannons,” using tear gas against sitting protesters, and detaining “at least 226 children” for their involvement in the protests.

Legal, Physical, and Digital Attacks

Simultaneously, as arrests and physical attacks against protesters and rights defenders have escalated, the government has faced accusations of using sophisticated spyware against anti-government critics. In November 2021, a number of individuals in Thailand received notifications from Apple regarding state-sponsored attacks. Several journalists and activists subsequently pressed on the government’s deployment of surveillance technologies against civil society. In that same month, government spokesman Thanakorn Wangboonkongchana argued that the report of state-sponsored attacks “is untrue,” as “the government respects individual liberties,” while Digital Economy and Society Minister Chaiwut Thanakamanusorn stated in December 2021 that he “can guarantee there are no attacks on anyone’s information.”

Despite these denials from Thai authorities, this report shows that numerous Thai activists and their lawyers’ phones were hacked with Pegasus spyware. Furthermore, the timeline of the infections suggests that these attacks were conducted as part of efforts to crack down on individuals that call for democratic reform. Circumstantial evidence also indicates that one or more elements of the Thai government may be responsible for this espionage campaign.

Dubious Denials Enable Human Rights Abuses

NSO Group argues that its software is to be used against criminals and terrorists and is sold only to governments. However, we have documented the abuse of Pegasus against numerous victims in multiple countries, including scientists, journalists, and lawyers. In Thailand, our previous research indicates that at least three government agencies had contracted with Circles, a complementary product to Pegasus that allows for interception of phone calls and SMS. This finding is part of a broader trend seen in Thailand where the government has been engaged in increased efforts to monitor or control information since the 2014 coup.

When Free Speech is Illegal

NSO Group has denied any wrongdoing and maintains that its products are to be used “in a legal manner and according to court orders and the local law of each country.” This justification is problematic, given the presence of local laws that infringe on international human rights standards and the lack of judicial oversight, transparency, and accountability in governmental surveillance, which could result in abuses of power. In Thailand, for example, Section 112 of the Criminal Code (also known as the lèse-majesté law), which criminalizes defamation, insults, and threats to the Thai royal family, has been criticized for being “fundamentally incompatible with the right to freedom of expression,” while the amended Computer Crime Act opens the door to potential rights violations, as it “gives overly broad powers to the government to restrict free speech [and] enforce surveillance and censorship.” Both laws have been used in concert to prosecute lawyers and activists, some of whom were targeted with Pegasus.

NSO’s Dubious “Internal Investigations”

NSO Group regularly responds to reports of abuse by stating that they have an ‘internal’ investigations process, and that without reports via those channels, they are limited in their ability to investigate cases. To evaluate the seriousness of this claim, Human Rights Watch followed NSO’s process and submitted a case for investigation along with supporting documentation. After five months had elapsed, NSO provided a two-sentence response:

“This issue has been investigated to the best of our ability based on the information provided to us. We have not seen evidence that Ms. Fakih’s number, provided below had been targeted using the Pegasus system by our existing customer’s. [sic]”

As Human Rights Watch points out, this highly limited response underlines the obvious deficiencies in NSO’s approach. No mention, for example, is made of the possibility that (a) the responsible party was no longer a customer at the time the reply was written (b) the evidence analyzed or supplied by NSO’s customers and used for the ‘investigation’ was incomplete.

Ongoing Failure to Protect Human Rights

This report thus underscores NSO Group’s failure to respect human rights abroad, despite the internationally-recognized responsibility of private sector actors not only “to respect and protect human rights,” but also to “provide remedy for rights violations, regardless of whether governments are able or willing to protect these rights.” Additionally, it highlights the Thai government’s use of Pegasus as being entirely out of step with states’ obligations under international human rights law, such as the principles of legality, necessity, proportionality, and legitimate aim.

Acknowledgements

We are especially grateful for the consent and participation of all victims, and suspected targets, in this investigation. Without their willingness to share materials for analysis, and tell their story, this report would not have been possible.

We are grateful to Siena Anstis, Miles Kenyon, Celine Bauwens, Jeff Knockel, and Adam Senft of the Citizen Lab for review and copy editing, and to Mari Zhou for the report image.

Special thanks to Amnesty International’s Security Lab for independent validation of a selection of victim devices for this report.

Special thanks to iLaw and DigitalReach, as well as other civil society organizations who choose not to be named, for their invaluable assistance in this investigation.

Special thanks to TNG.

- During the course of the investigation it was determined that several iLaw staff were also victims of Pegasus spyware, and they are noted in the report.↩︎

- Typo corrected on: July 20, 2022.

- Typo corrected on: July 20, 2022.

- We collected forensic artifacts with the consent of the device owner. All research involving human subjects conducted at the Citizen Lab is governed under research ethics protocols reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board.↩︎

- Amnesty International’s Security Lab refers to this exploit as “Megalodon.”↩︎