- Cisco Talos recently discovered a new malware family we’re calling “HTTPSnoop” being deployed against telecommunications providers in the Middle East.

- HTTPSnoop is a simple, yet effective, backdoor that consists of novel techniques to interface with Windows HTTP kernel drivers and devices to listen to incoming requests for specific HTTP(S) URLs and execute that content on the infected endpoint.

- We also discovered a sister implant to “HTTPSnoop” we’re naming “PipeSnoop,” which can accept arbitrary shellcode from a named pipe and execute it on the infected endpoint.

- We identified DLL- and EXE-based versions of the implants that masquerade as legitimate security software components, specifically extended detection and response (XDR) agents, making them difficult to detect.

- We assess with high confidence that both implants belong to a new intrusion set we’re calling “ShroudedSnooper.” Based on the HTTP URL patterns used in the implants, such as those mimicking Microsoft’s Exchange Web Services (EWS) platform, we assess that this threat actor likely exploits internet-facing servers and deploys HTTPSnoop to gain initial access.

- This activity is a continuation of a trend we have been monitoring over the last several years in which sophisticated actors are frequently targeting telecoms. This sector was consistently a top-targeted industry vertical in 2022, according to Cisco Talos Incident Response data.

ShroudedSnooper activity highlights latest threat to telecommunications entities

This specific cluster of implants involving HTTPSnoop and PipeSnoop and associated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) do not match a known group that Talos tracks. We are therefore attributing this activity to a distinct intrusion set we’re calling “ShroudedSnooper.”

In recent years, there have been many instances of state-sponsored actors and sophisticated adversaries targeting telecommunications organizations around the world. In 2022, this sector was consistently a top-targeted vertical in Talos IR engagements. Telecommunications companies typically control a vast number of critical infrastructure assets, making them high-priority targets for adversaries looking to cause significant impact. These entities often form the backbone of national satellite, internet and telephone networks upon which most private and government services rely. Furthermore, telecommunications companies can serve as a gateway for adversaries to access other businesses, subscribers or third-party providers.

Our IR findings are consistent with reports from other cybersecurity firms outlining various attack campaigns targeting telecommunications companies globally. In 2021, CrowdStrike disclosed a years-long campaign by the LightBasin (UNC1945) advanced persistent threat (APT) targeting 13 telecommunications companies globally using Linux-based implants to maintain long-term access in compromised networks. That same year, McAfee discovered activity targeting telecommunication firms in Europe, the U.S. and Asia dubbed “Operation Diànxùn” linked to the Chinese APT group MustangPanada (RedDelta). This campaign heavily relied on the PlugX malware implant. Also in 2021, Recorded Future reported that four distinct Chinese state-sponsored APT groups were targeting the email servers of a telecommunications firm in Afghanistan, again using the PlugX implant.

The targeting of telecommunications firms in middle-east Asia is also quite prevalent. In January 2021, Clearsky disclosed the “Lebanese Cedar” APT leveraging web shells and the “Explosive” RAT malware family to target telecommunication firms in the U.S., U.K. and middle-east Asia. In a separate campaign, Symantec noted the MuddyWater APT targeting telecommunication organizations in the Middle East, deploying web shells on Exchange Servers to instrument script-based malware and dual-use tools to carry out hands-on-keyboard activity.

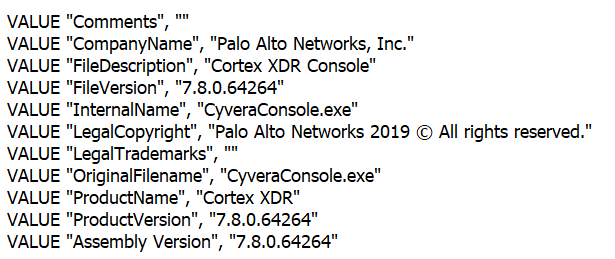

Masquerading as a security component

We also discovered both HTTPSnoop and PipeSnoop masquerading as components of Palo Alto Networks’ Cortex XDR application. The malware executable is named “CyveraConsole.exe,” which is the application that contains the Cortex XDR agent for Windows. The variants of both HTTPSnoop and PipeSnoop we discovered had their compile timestamps tampered with but masqueraded as XDR agent from version 7.8.0.64264. Cortex XDR v7.8 was released on Aug. 7, 2022, and decommissioned on April 24, 2023. Therefore, it is likely that the threat actors operated this cluster of implants during the aforementioned timeframe. For example, one of the “CyveraConsole.exe” implants was compiled on Nov. 16, 2022, falling approximately in the middle of this time window of the life of Cortex XDR v7.8.

A primer on HTTPSnoop

HTTPSnoop is a simple, yet effective, new backdoor that uses low-level Windows APIs to interact directly with the HTTP device on the system. It leverages this capability to bind to specific HTTP(S) URL patterns to the endpoint to listen for incoming requests. Any incoming requests for the specified URLs are picked up by the implant, which then proceeds to decode the data accompanying the HTTP request. The decoded HTTP data is, in fact, shellcode that is then executed on the infected endpoint.

HTTPSnoop consists of the same code across all observed variants, with the key difference in samples being the URL patterns that it listens for. So far, we have discovered three variations in the configuration:

- Generic HTTP URL-based: Listens for generic HTTP URLs specified by the implant.

- EWS-related URLs listener: Listen for URLs that mimic Microsoft’s Exchange Web Services (EWS) API.

- OfficeCore’s Location Based Services (LBS)-related URL listener: Listens for URLs that mimic OfficeCore’s LBS/OfficeTrack and telephony applications.

HTTPSnoop variants

The DLL-based variants of HTTPSnoop usually rely on DLL hijacking in benign applications and services to get activated on the infected system. The attackers initially crafted the first variant of the implant on April 17, 2023, so that it could bind to specific HTTP URLs on the endpoint to listen for incoming shellcode payloads that are then executed on the infected endpoint. These HTTP URLs resemble those of Microsoft’s Exchange Web Services (EWS) API, a product that enables applications to access mailbox items.

A second variant, generated on April 19, 2023, is nearly identical to the initial version of HTTPSnoop from April 17. The only difference is that this second variant is configured to listen to a different set of HTTP URLs on Ports 80 and 443 exclusively, indicating that the attackers may have intended to focus on a separate non-EWS internet-exposed web server.

The attackers then built a third variant that consisted of a killswitch URL and one other URL that the implant listens to. This implant was crafted on April 29, 2023. This version of the implant was likely an effort to minimize the number of URLs that the implant listens to, to reduce the likelihood of detection.

HTTPSnoop analysis

The DLL analyzed simply consists of two key components:

- Encoded Stage 2 shellcode.

- Encoded Stage 2 configuration.

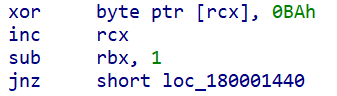

The malicious DLL on activation will XOR decode the Stage 2 configuration and shellcode and run it.

Stage 2 analysis

Stage 2 is a single-byte XOR’ed backdoor shellcode that uses the accompanying configuration data to listen for incoming shellcode to execute on the infected endpoint. As part of Stage 2, the sample proceeds to make numerous calls to kernel devices in order to set up a web server endpoint for its backdoor. The implant opens a handle to “DeviceHttpCommunication” and calls the HTTP driver API “http.sys!UlCreateServerSession” with IOCTL code 0x1280000to initialize the connection to the HTTP server. The sample continues by creating a new URL group using http.sys!UlCreateUrlGroup with IOCTL code 0x128010 opens a request queue device “DeviceHttpReqQueue” and sets the new URL group for the session using http.sys!UlSetUrlGroupwith IOCTL code 0x12801d.

Using the decrypted configuration the sample begins to feed the URLs to the HTTP server via http.sys!UlAddUrlToUrlGroup with IOCTL code l 0x128020. This binds the specified URL patterns to a listenable endpoint for the malware to communicate. The implant takes care to not overwrite already existing URL patterns being serviced by the HTTP server, to coexist with previous configurations on the server, such as EWS and prevent URL listener collisions.

With the URLs bound to listen on the kernel’s web server, the malware proceeds to listen in a loop for incoming HTTP requests, carried out via http.sys!UlReceiveHttpRequest. If the headers from the HTTP request contain a configured keyword, in this particular sample’s case, “api_delete”, the listening loop for the infection will terminate. Once a request comes in, it creates a new thread and calls http.sys!UlReceiveEntityBody with IOCTL codes 0x12403b, or 0x12403a when running Windows Server 2022 version 21H2, to receive the full message body from the implant operator. If the request has valid data, the sample proceeds to process the request or else returns an HTTP 302 Found redirect response to the requester.

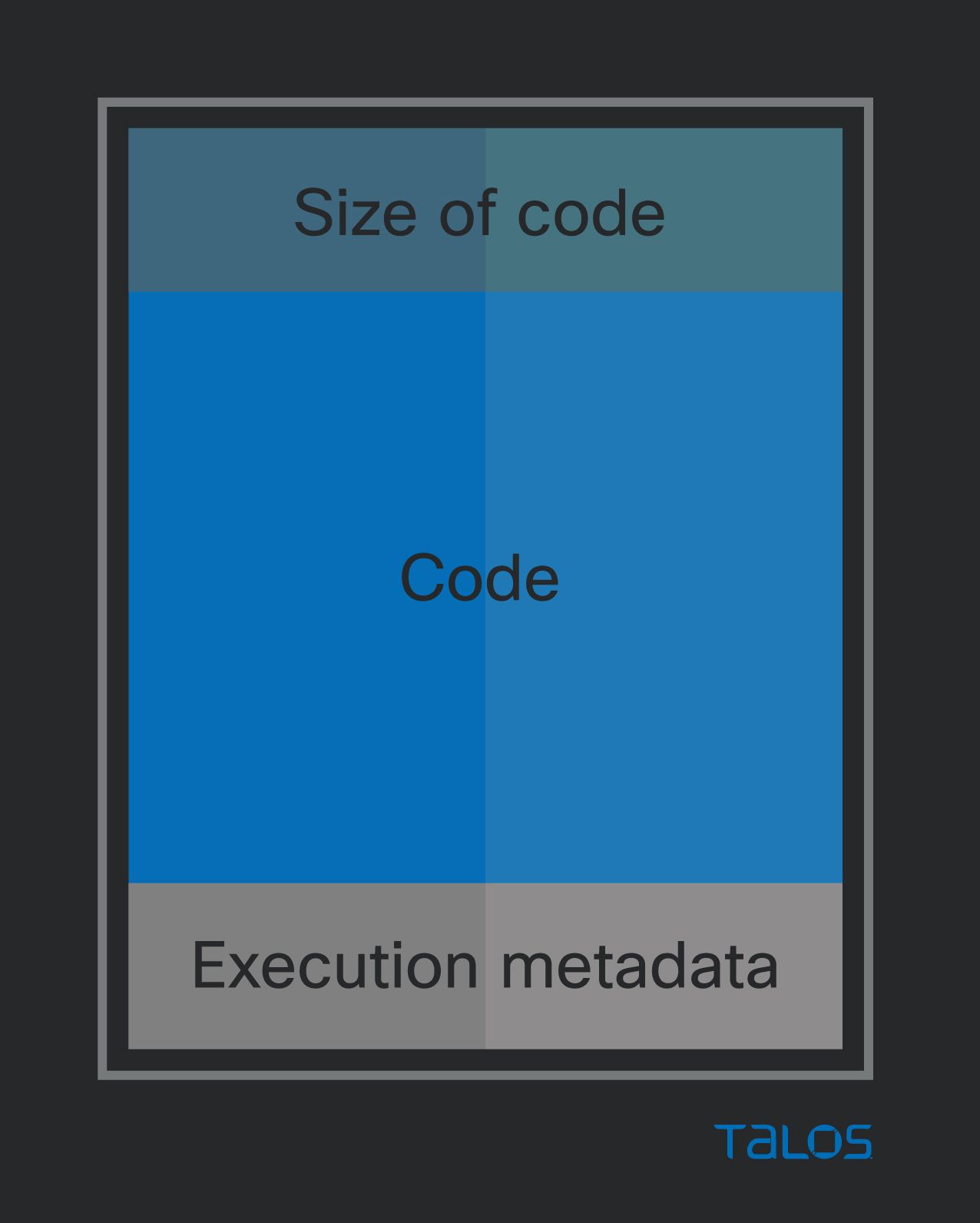

Valid data comes in the form of a base64-encoded request body. Upon decoding, it proceeds to use the first byte of data to single-byte XOR-decode the rest of the data. Once decrypted, a simple data structure is unveiled. The payload received from the operator is an arbitrary shellcode payload. The execution metadata consists of an uninitialized pointer and size, plus the size of the metadata structure, which is a constant 0x18. These uninitialized pointers are initialized by the execution of the shellcode, used to pass back data to the implant to eventually send back to the operator as a response to the HTTP request.

The ultimate result of the execution of the arbitrary shellcode is returned to the requester (operator) in the form of a base64-encoded XOR-encoded blob. The first byte of the response is a random letter from the ASCII table, which is used to XOR the rest of the response. With this, the malware sends back a 200 OK response with the encoded execution result in its body via http.sys!UlSendHttpResponsewith IOCTL code 0x12403f.

Introducing PipeSnoop

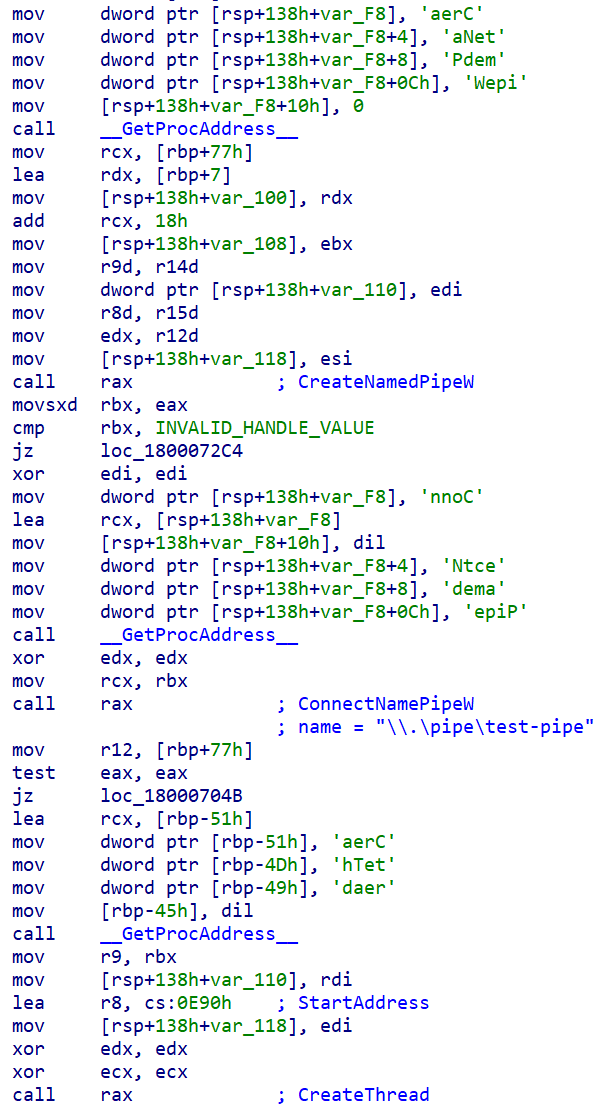

The PipeSnoop implant, created in May 2023, is a simple implant that can run arbitrary shellcode payloads on the infected endpoint by reading from an IPC pipe. Although semantically similar, the PipeSnoop implant should not be considered an upgrade of HTTPSnoop. Both implants are likely designed to work under different environments. The HTTP URLs used by HTTPSnoop along with the binding to the built-in Windows web server indicate that it was likely designed to work on internet-exposed web and EWS servers. PipeSnoop, however, as the name may imply, reads and writes to and from a Windows IPC pipe for its input/output (I/O) capabilities This suggests the implant is likely designed to function further within a compromised enterprise–instead of public-facing servers like HTTPSnoop — and probably is intended for use against endpoints the malware operators deem more valuable or high-priority. PipeSnoop is likely used in conjunction with another component that is capable of feeding it the required shellcode. (This second component is currently unknown.)

PipeSnoop analysis

PipeSnoop is a simple backdoor that, much like HTTPSnoop, aims to act as a backdoor executing arbitrary shellcode on the infected endpoint. In contrast to HTTPSnoop however, PipeSnoop does not rely on initiating and listening for incoming connections via an HTTP server. As indicated by the name, PipeSnoop will simply attempt to connect to a pre-existing named pipe on the system. Named pipes are a common means of Inter-Process Communication (IPC) on the Windows operating system. The key requirement here is that the named pipe that PipeSnoop connects to should have been already created/established – PipeSnoop does not attempt to create the pipe, it simply tries to connect to it. This capability indicates that PipeSnoop cannot function as a standalone implant (unlike HTTPSnoop) on the endpoint. It needs a second component, that acts as a server that will obtain arbitrary shellcode via some methods and will then feed the shellcode to PipeSnoop via the named pipe.

Masquerading as benign traffic on the wire

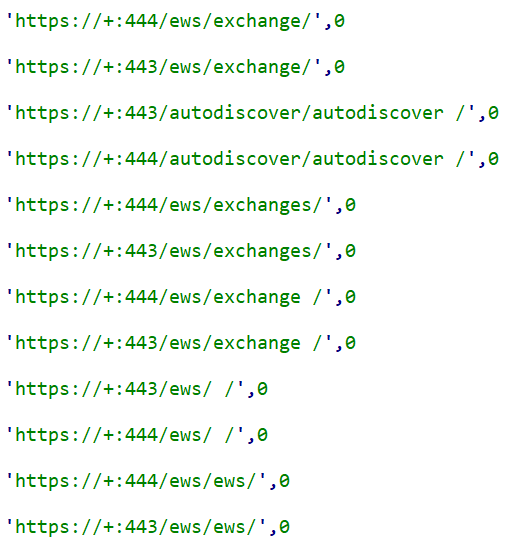

We’ve observed HTTPSnoop listening for URL patterns that make it look like the infected system being contacted is a server hosting Microsoft’s Exchange Web Services (EWS) API. The URLs consisted of “ews” and “autodiscover” keywords over Ports 443 and 444:

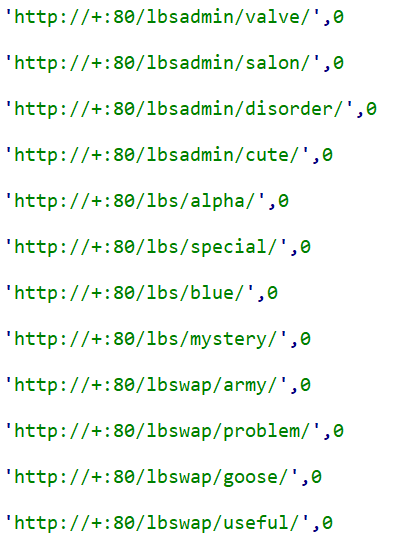

Some of the HTTPSnoop implants use HTTP URLs that masquerade as those belonging to OfficeTrack, an application developed by software company OfficeCore that helps users manage different administrative tasks. In several instances, we see URLs ending in “lbs” and “LbsAdmin,” references to the application’s earlier name (OfficeCore’s LBS System) before it was later rebranded as OfficeTrack. OfficeTrack is currently marketed as a workforce management solution geared toward providing coverage for logistics, order orchestration and equipment control. OfficeTrack is especially marketed towards telecommunication firms. Some of the LBS URLs used by HTTPSnoop are:

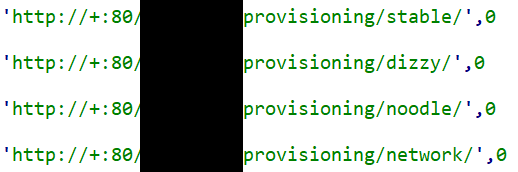

The HTTP URLs also consist of patterns mimicking provisioning services from an Israeli telecommunications company. This telco may have used OfficeTrack in the past and/or currently uses this application, based on open-source findings.

Some of the URLs in the HTTPSnoop implant are also related to those of systems from the telecommunications firm:

Coverage

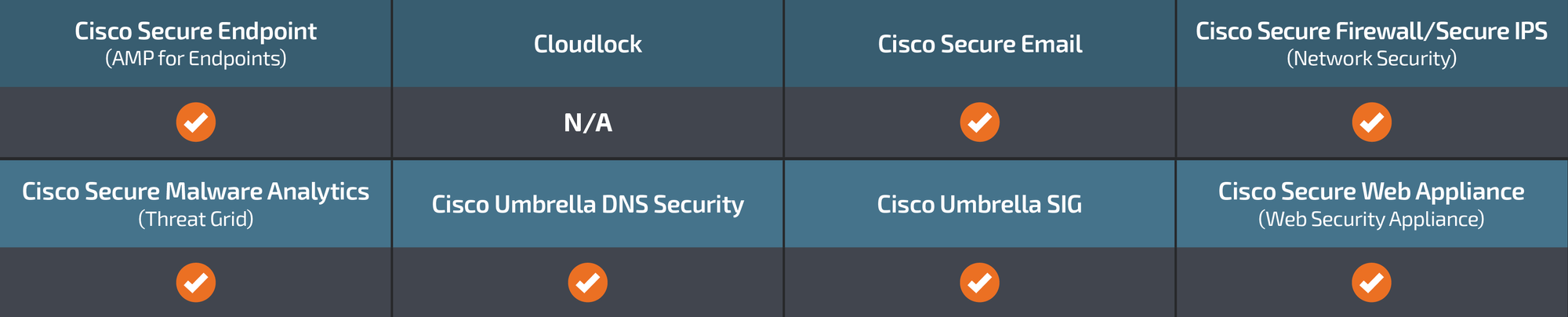

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Cisco Secure Endpoint (formerly AMP for Endpoints) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Try Secure Endpoint for free here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco Secure Email (formerly Cisco Email Security) can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign. You can try Secure Email for free here.

Cisco Secure Firewall (formerly Next-Generation Firewall and Firepower NGFW) appliances such as Threat Defense Virtual, Adaptive Security Appliance and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Cisco Secure Malware Analytics (Threat Grid) identifies malicious binaries and builds protection into all Cisco Secure products.

Umbrella, Cisco’s secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network. Sign up for a free trial of Umbrella here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance (formerly Web Security Appliance) automatically blocks potentially dangerous sites and tests suspicious sites before users access them.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firewall Management Center.

Cisco Duo provides multi-factor authentication for users to ensure only those authorized are accessing your network.

Note: We have shared our findings with both Microsoft and Palo Alto Networks for this threat and intrusion set.

ClamAV detections are available for this threat:

Win.Trojan.WCFBackdoor

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Indicators of Compromise associated with this threat can be found here.

Source: https://blog.talosintelligence.com/introducing-shrouded-snooper/